Sintashta culture

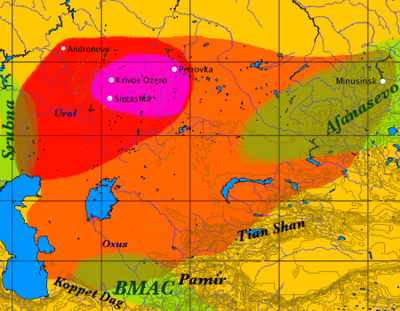

The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture[1] or Sintashta-Arkaim culture,[2] is a late Middle Bronze Age archaeological culture of the northern Eurasian steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2200–1800 BCE,[3][4][5] or as recent publication by Stephan Lindner claims, based on another series of 19 calibrated radiocarbon datings, that the whole Sintashta-Petrovka complex belongs to c. 2050-1750 BCE.[6] Although recently Ventresca Miller et al. still claimed a period of 2400-1800 BCE,[7][8] based on 44 earlier C14 calibrated datings by Russian Academy of Sciences, which some other researchers consider to be outdated. The culture is named after the Sintashta archaeological site, in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia.

| |

| Period | Bronze Age |

|---|---|

| Dates | 2400–1800 BCE |

| Type site | Sintashta |

| Major sites | Sintashta Arkaim Petrovka |

| Characteristics | Extensive copper and bronze metallurgy Fortified settlements Elaborate weapon burials Earliest known chariots |

| Preceded by | Corded Ware culture Poltavka culture Abashevo culture |

| Followed by | Andronovo culture |

The Sintashta culture is thought to represent an eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture. It is widely regarded as the origin of the Indo-Iranian languages. The earliest known chariots have been found in Sintashta burials, and the culture is considered a strong candidate for the origin of the technology, which spread throughout the Old World and played an important role in ancient warfare.[9] Sintashta settlements are also remarkable for the intensity of copper mining and bronze metallurgy carried out there, which is unusual for a steppe culture.[10]

Origin

According to Russian archaeologists, the Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures, the Poltavka culture and the Abashevo culture. Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture.[2] It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the "Andronovo horizon".[1] Results from a genetic study published in Nature in 2015 suggested that the Sintashta culture emerged as a result of an eastward migration of peoples from the Corded Ware culture.[11]

Morphological data suggests that the Sintashta culture might have emerged as a result of a mixture of steppe ancestry from the Poltavka culture and Catacomb culture, with ancestry from Neolithic forest hunter-gatherers.[lower-alpha 1]

Even though other researchers think it's an outdated chronology, Ventresca Miller et al. still claim that the first Sintashta settlements appeared around 2400 BCE and lasted until 1800 BCE with population estimates in each site ranging from 200 to 700 individuals,[7] during a period of climatic change that saw the already arid Kazakh steppe region become even more cold and dry. The marshy lowlands around the Ural and upper Tobol rivers, previously favoured as winter refuges, became increasingly important for survival. Under these pressures both Poltavka and Abashevo herders settled permanently in river valley strongholds, eschewing more defensible hill-top locations.[13] Ventresca Miller et al., also claims that "by 2300 cal BCE, Middle Bronze Age sites associated with Sintashta and Petrovka cultural groups in northern Kazakhstan heavily exploited domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats alongside horses with occasional hunting of wild fauna".[8]

Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltavka settlements or close to Poltavka cemeteries, and Poltavka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery.[14]

Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, derived from the Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture, a collection of Corded Ware settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist.[14]

Society

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Philology

|

|

Origins |

|

Archaeology Pontic Steppe

Caucasus East Asia Eastern Europe Northern Europe Pontic Steppe Northern/Eastern Steppe Europe

South Asia Steppe Europe Caucasus India |

|

Peoples and societies Indo-Aryans Iranians

East Asia Europe East Asia Europe

Indo-Aryan Iranian

|

|

Religion and mythology

Indo-Aryan Iranian Others Europe

|

|

Linguistic identity

The people of the Sintashta culture are thought to have spoken Proto-Indo-Iranian, the ancestor of the Indo-Iranian language family.[15] This identification is based primarily on similarities between sections of the Rig Veda, an Indian religious text which includes ancient Indo-Iranian hymns recorded in Vedic Sanskrit, with the funerary rituals of the Sintashta culture as revealed by archaeology.[16] Many cultural similarities with Sintashta have also been detected in the Nordic Bronze Age of Scandinavia.[lower-alpha 2]

There is linguistic evidence of interaction between Finno-Ugric and Indo-Iranian languages, showing influences from the Indo-Iranians into the Finno-Ugric culture.[17]

From the Sintashta culture the Indo-Iranian followed the migrations of the Indo-Iranians to Anatolia, India and Iran.[18][19] From the 9th century BCE onward, Iranian languages also migrated westward with the Scythians back to the Pontic steppe where the proto-Indo-Europeans came from.[19]

Warfare

The preceding Abashevo culture was already marked by endemic intertribal warfare;[20] intensified by ecological stress and competition for resources in the Sintashta period, this drove the construction of fortifications on an unprecedented scale and innovations in military technique such as the invention of the war chariot. Increased competition between tribal groups may also explain the extravagant sacrifices seen in Sintashta burials, as rivals sought to outdo one another in acts of conspicuous consumption analogous to the North American potlatch tradition.[13]

Sintashta artefact types such as spearheads, trilobed arrowheads, chisels, and large shaft-hole axes were taken east.[21] Many Sintashta graves are furnished with weapons, although the composite bow associated later with chariotry does not appear. Sintashta sites have produced finds of horn and bone, interpreted as furniture (grips, arrow rests, bow ends, string loops) of bows; there is no indication that the bending parts of these bows included anything other than wood.[22] Arrowheads are also found, made of stone or bone rather than metal. These arrows are short, 50–70 cm long, and the bows themselves may have been correspondingly short.[22]

Metal production

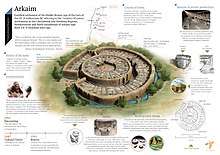

The Sintashta economy came to revolve around copper metallurgy. Copper ores from nearby mines (such as Vorovskaya Yama) were taken to Sintashta settlements to be processed into copper and arsenical bronze. This occurred on an industrial scale: all the excavated buildings at the Sintashta sites of Sintashta, Arkaim and Ust'e contained the remains of smelting ovens and slag.[13]

Much of Sintashta metal was destined for export to the cities of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) in Central Asia. The metal trade between Sintashta and the BMAC for the first time connected the steppe region to the ancient urban civilisations of the Near East: the empires and city-states of Iran and Mesopotamia provided an almost bottomless market for metals. These trade routes later became the vehicle through which horses, chariots and ultimately Indo-Iranian-speaking people entered the Near East from the steppe.[23][24]

Aerial view of the Arkaim site

Aerial view of the Arkaim site View of the Arkaim site and surrounding landscape

View of the Arkaim site and surrounding landscape Excavation and partial building reconstruction

Excavation and partial building reconstruction Arkaim infographic

Arkaim infographic chariot model, Arkaim museum

chariot model, Arkaim museum

Physical type

Physical remains of the Sintashta people has revealed that they were Europoids with dolichocephalic skulls. Sintashta skulls are very similar to those of the preceding Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture and Abashevo culture, which ultimately trace their origin to Central Europe, and those of the succeeding Srubnaya culture and Andronovo culture. Skulls of the related Potapovka culture are less dolichocephalic, possibly as a result of admixture with between Sintastha people and descendants of the Yamnaya culture and Poltavka culture, who although being of a similar robust Europoid type, were less dolichocephalic than Sintashta. The physical type of Abashevo, Sintashta, Andronovo and Srubnaya is later observed among the Scythians.[lower-alpha 3]

Genetics

Allentoft 2015, published in Nature, the remains of four individuals ascribed to the Sintastha culture were analyzed. One male carried haplogroup R1a and J1c1b1a, while the other carried R1a1a1b and J2b1a2a. The two females carried U2e1e and U2e1h respectively.[11][26] The study found a close autosomal genetic relationship between peoples of Corded Ware culture and Sintashta culture, which "suggests similar genetic sources of the two," and may imply that "the Sintashta derives directly from an eastward migration of Corded Ware peoples."[11] Sintashta individuals and Corded Ware individuals both had a relatively higher ancestry proportion derived from the Central Europe, and both differed markedly in such ancestry from the population of the Yamnaya Culture and most individuals of the Poltavka Culture that preceded Sintashta in the same geographic region.[lower-alpha 4] The Bell Beaker culture, the Unetice culture and contemporary Scandinavian cultures were also found to be closely genetically related to Corded Ware. A particularly high lactose tolerance was found among Corded Ware and the closely related Nordic Bronze Age.[lower-alpha 5] In addition, the study found the Sintashta culture to be closely genetically related to the succeeding Andronovo culture.[lower-alpha 6]

Narasimhan 2019, published in Science, analyzed the remains of several members of the Sintashta culture. mtDNA was extracted from two females buried at the Petrovka settlement. They were found to be carrying subclades of U2 and U5. The remains of fifty individuals from the fortified Sintastha settlement of Kamennyi Ambar was analyzed. This was the largest sample of ancient DNA ever sampled from a single site. The Y-DNA from thirty males was extracted. Eighteen carried R1a and various subclades of it (particularly subclades of R1a1a1), five carried subclades of R1b (particularly subclades of R1b1a1a), three carried R1, two carried Q1a and a subclade of it, one carried I2a1a1a, and one carried P1. The majority of mtDNA samples belonged to various subclades of U, while W, J, T, H and K also occurred. A Sintashta male buried at Samara was found to be carrying R1b1a1a2 and J1c1b1a. The authors of the study found the Sintashta people to be closely genetically related to the people of the Corded Ware culture, the Srubnaya culture, the Potapovka culture, and the Andronovo culture. These were found to harbor mixed ancestry from the Yamnaya culture and peoples of the Central European Middle Neolithic.[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8] Sintashta people were deemed "genetically almost indistinguishable" from samples taken from the northwestern areas constituting the core of the Andronovo culture, which were "genetically largely homogeneous". The genetic data suggested that the Sintashta culture was ultimately derived of a remigration of Central European peoples with steppe ancestry back into the steppe.[lower-alpha 9] Some Sintastha individuals displayed similarites with earlier samples collected at Khvalynsk.[12]

Notes

- "Morphological data suggests that both Fedorovka and Alakul’ skeletons may be related to Sintashta groups, which in turn may reflect admixture of Neolithic forest HGs and steppe pastoralists, descendants of the Catacomb and Poltavka cultures."[12]

- "There are many similarities between Sintasthta/Androvono rituals and those described in the Rig Veda and such similarities even extend as far as to the Nordic Bronze Age."[11]

- "[M]assive broad-faced proto-Europoid type is a trait of post-Mariupol’ cultures, Sredniy Stog, as well as the Pit-grave culture of the Dnieper’s left bank, the Donets, and Don... During the period of the Timber-grave culture the population of the Ukraine was represented by the medium type between the dolichocephalous narrow-faced population of the Multi-roller Ware culture (Babino) and the more massive broad-faced population of the Timber-grave culture of the Volga region... The anthropological data confirm the existence of an impetus from the Volga region to the Ukraine in the formation of the Timber-grave culture. During the Belozerka stage the dolichocranial narrow-faced type became the prevalent one. A close affinity among the skulls of the Timber-grave, Belozerka, and Scythian cultures of the Pontic steppes, on the one hand, and of the same cultures of the forest-steppe region, on the other, has been shown... This proves the genetical continuity between the Iranian-speeking Scythian population and the previous Timber-grave culture population in the Ukraine... The heir of the Neolithic Dnieper-Donets and Sredniy Stog cultures was the Pit-grave culture. Its population possessed distinct Europoid features, was tall, with massive skulls... The tribes of the Abashevo culture appear in the forest-steppe zone, almost simultaneously with the Poltavka culture. The Abashevans are marked by dolichocephaly and narrow faces. This population had its roots in the Balanovo and Fatyanovo cultures on the Middle Volga, and in Central Europe... [T]he early Timber-grave culture (the Potapovka) population was the result of the mixing of different components. One type was massive, and its predecessor was the Pit-grave-Poltavka type. The second type was a dolichocephalous Europoid type genetically related to the Sintashta population... One more participant of the ethno-cultural processes in the steppes was that of the tribes of the Pokrovskiy type. They were dolichocephalous narrow-faced Europoids akin to the Abashevans and different from the Potapovkans... The majority of Timber-grave culture skulls are dolichocranic with middle-broad faces. They evidence the significant role of Pit-grave and Poltavka components in the Timber-grave culture population... One may assume a genetic connection between the populations of the Timber-grave culture of the Urals region and the Alakul’ culture of the Urals and West Kazakhstan belonging to a dolichocephalous narrow-face type with the population of the Sintashta culture... [T]he western part of the Andronovo culture population belongs to the dolichocranic type akin to that of the Timber-grave culture.[25]

- Allentoft et al. (2015) analysed ancient DNA recovered from remains at four Sintashta sites. The five samples analysed included the mitochondrial DNA haplogroups U2e, J1, J2 and N1a. The two male individuals both belonged to Y-chromosome haplogroup R1a1.[11]

- "European Late Neolithic and Bronze Age cultures such as Corded Ware, Bell Beakers, Unetice, and the Scandinavian cultures are genetically very similar to each other... The close affinity we observe between peoples of Corded Ware and Sintashta cultures suggests similar genetic sources of the two... Among Bronze Age Europeans, the highest tolerance frequency was found in Corded Ware and the closely-related Scandinavian Bronze Age cultures."[11]

- "The Andronovo culture, which arose in Central Asia during the later Bronze Age, is genetically closely related to the Sintashta peoples, and clearly distinct from both Yamnaya and Afanasievo. Therefore, Andronovo represents a temporal and geographical extension of the Sintashta gene pool."[11]

- "We observed a main cluster of Sintashta individuals that was similar to Srubnaya, Potapovka, and Andronovo in being well modeled as a mixture of Yamnaya-related and Anatolian Neolithic (European agriculturalist-related) ancestry."[12]

- "Genetic analysis indicates that the individuals in our study classified as falling within the Andronovo complex are genetically similar to the main clusters of Potapovka, Sintashta, and Srubnaya in being well modeled as a mixture of Yamnaya-related and early European agriculturalist-related or Anatolian agriculturalist-related ancestry."[12]

- "Many of the samples from this group are individuals buried in association with artifacts of the Corded Ware, Srubnaya, Petrovka, Sintashta andAndronovo complexes, all of which harboreda mixture of Steppe_EMBA ancestry and ancestry from European Middle Neolithic agriculturalists (Europe_MN). This is consistent with previous findings showing that following westward movement of eastern European populations and mixture with local European agriculturalists, there was an eastward reflux back beyond the Urals."[27]

References

- Koryakova 1998b.

- Koryakova 1998a.

- Chernykh, E. N. (2008). "Formation of the Eurasian 'Steppe Belt' of Stockbreeding Cultures: Viewed through the Prism of Archaeometallurgy and Radiocarbon Dating", in Archaeology, Ethnology & Anthropology of Eurasia 35/3 (2008), Elsevier: "...radiocarbon estimates...accumulated and systematized at the Laboratory of the Institute of Archaeology, Russian Academy of Sciences (Moscow)...Sintashta, 44 dates; Abashevo, 22; and Petrovka, only nine...the ranges of sum probabilities within the 68% limits: they strikingly coincide, falling between the 22nd and the 18th/17th cent. BC..." (pp. 38 and 48).

- Chernykh, E. N., (2009). Formation of the Eurasian Steppe Belt Cultures: Viewed Through the Lens of Archaeometallurgy and Radiocarbon Dating, in B. Hanks & K. Linduff (eds.), Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals and Mobility, Cambridge University Press, pp. 128-133.

- Parpola, Asko, (2017). "Finnish vatsa - Sanskrit vatshá - and the formation of Indo-Iranian and Uralic languages", in SUSA/JSFOu 96, 2017, p. 249.

- Lindner, Stephan, (2020). "Chariots in the Eurasian Steppe: a Bayesian approach to the emergence of horse-drawn transport in the earlysecond millennium BC", in Antiquity, Vol 94, Issue 374, April 2020, p. 367: "...The 12 calibrated radiocarbon dates belonging to the Sintashta horizon range between 2050 and 1760 cal BC (at 95.4% confidence; Epimakhov & Krause 2013: 137). These dates correlate well with the seven AMS-sampled Sintashta graves in the associated KA-5cemetery, which date to 2040–1730 cal BC (95.4% confidence...)".

- Ventresca Miller, Alicia R., et al., (2020 b). "Ecosystems Engineering Among Ancient Pastoralists in Northern Central Asia", in Frontiers in Earth Science, Volume 8, Article 168, 2 June 2020, p. 6: "...Middle Bronze Age (2400-1800 cal BCE) people, often referred to as Sintashta, constructed nucleated settlements, with population estimates ranging from 200 to 700 individuals..."

- Ventresca Miller, A. R., et al., (2020 a). "Close management of sheep in ancient Central Asia: evidence for foddering, transhumance, and extended lambing seasons during the Bronze and Iron Ages", in STAR, Science & Technology of Archaeological Research, p. 2: "...By 2300 cal BCE, Middle Bronze Age sites associated with Sintashta and Petrovka cultural groups in northern Kazakhstan heavily exploited domesticated cattle, sheep, and goats alongside horses with occasional hunting of wild fauna..."

- Kuznetsov 2006.

- Hanks & Linduff 2009.

- Allentoft 2015.

- Narasimhan 2019.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 390–391

- Anthony 2007, pp. 386–388.

- Mallory & Mair 2008, p. 261.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 408–411.

- Kuzmina 2007, p. 222.

- Anthony 2007.

- Beckwith 2009.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 383–384

- Rawson, Jessica (Autumn 2015). "Steppe Weapons in Ancient China and the Role of Hand-to-hand Combat". The National Palace Museum Research Quarterly. 33 (1): 49: See reference 33 - E. N. Chernykh, Ancient Metallurgy in the USSR, The Early Metal Age, 225, fig. 78.

- Bersenev, Andrey; Epimakhov, Andrey; Zdanovich, Dmitry (2011). "Bow and arrow. The Sintasha bow of the Bronze Age of the south Trans-Urals, Russia". In Marion Uckelmann; Marianne Modlinger; Steven Matthews (eds.). Bronze Age Warfare: Manufacture and Use of Weaponry. European Association of Archaeologists. Annual Meeting. Archaeopress. pp. 175–186. ISBN 978-1-4073-0822-7.

- Anthony 2007, p. 391.

- Anthony 2007, pp. 435–418.

- Kuzmina 2007, pp. 383-385.

- Mathieson 2015.

- 2019 & Narasimhan.

Sources

- Allentoft, ME (June 11, 2015). "Population genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia". Nature. Nature Research. 522 (7555): 167–172. doi:10.1038/nature14507. PMID 26062507.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Anthony, D. W. (2009). "The Sintashta Genesis: The Roles of Climate Change, Warfare, and Long-Distance Trade". In Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (eds.). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 47–73. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605376.005. ISBN 978-0-511-60537-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beckwith, Christopher I. (2009), Empires of the Silk Road, Princeton University Press

- Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (2009). "Late Prehistoric Mining, Metallurgy, and Social Organization in North Central Eurasia". In Hanks, B.; Linduff, K. (eds.). Social Complexity in Prehistoric Eurasia: Monuments, Metals, and Mobility. Cambridge University Press. pp. 146–167. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511605376.005. ISBN 978-0-511-60537-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koryakova, L. (1998a). "Sintashta-Arkaim Culture". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Retrieved 16 September 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Koryakova, L. (1998b). "An Overview of the Andronovo Culture: Late Bronze Age Indo-Iranians in Central Asia". The Center for the Study of the Eurasian Nomads (CSEN). Retrieved 16 September 2010.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kuznetsov, P. F. (2006). "The emergence of Bronze Age chariots in eastern Europe". Antiquity. 80 (309): 638–645. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00094096. Archived from the original on 2012-07-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kuzmina, Elena E. (2007). Mallory, J. P. (ed.). The Origin of the Indo-Iranians. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004160545.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mallory, J. P.; Mair, Victor H. (2008). The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 9780500283721.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mathieson, Iain (November 23, 2015). "Genome-wide patterns of selection in 230 ancient Eurasians". Nature. Nature Research. 528 (7583): 499–503. doi:10.1038/nature16152. PMC 4918750. PMID 26595274.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 365 (6457): eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- Stanislav A. Grigoriev, "Ancient Indo-Europeans" ISBN 5-88521-151-5