Samos

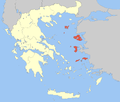

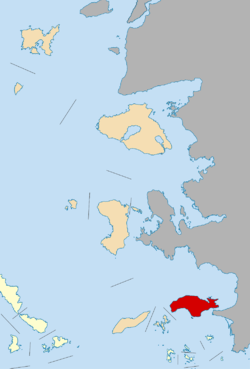

Samos (/ˈseɪmɒs/,[1] also US: /ˈsæmoʊs, ˈsɑːmɔːs/;[2][3][4] Greek: Σάμος [ˈsamos]) is a Greek island in the eastern Aegean Sea, south of Chios, north of Patmos and the Dodecanese, and off the coast of western Turkey, from which it is separated by the 1.6-kilometre (1.0 mi)-wide Mycale Strait. It is also a separate regional unit of the North Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional unit.

Samos Σάμος | |

|---|---|

Samos (town), capital of Samos | |

Seal | |

Samos within the North Aegean | |

Samos Samos within the North Aegean | |

| Coordinates: 37°45′N 26°50′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | North Aegean |

| Capital | Samos |

| Area | |

| • Total | 477.4 km2 (184.3 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 32,977 |

| • Density | 69/km2 (180/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes | 831 xx |

| Area codes | 2273 |

| Car plates | MO |

| Website | www |

In ancient times Samos was an especially rich and powerful city-state, particularly known for its vineyards and wine production.[5] It is home to Pythagoreion and the Heraion of Samos, a UNESCO World Heritage Site that includes the Eupalinian aqueduct, a marvel of ancient engineering. Samos is the birthplace of the Greek philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras, after whom the Pythagorean theorem is named, the philosophers Melissus of Samos and Epicurus, and the astronomer Aristarchus of Samos, the first known individual to propose that the Earth revolves around the sun. Samian wine was well known in antiquity, and is still produced on the island.

The island was governed by the semi-autonomous Principality of Samos under Ottoman suzerainty from 1835 until it joined Greece in 1912.[5]

Etymology

Strabo derived the name from the Phoenician word sama meaning "high".[6][7][8]

Geography

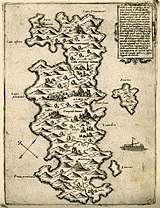

The area of the island is 477.395 km2 (184.3 sq mi),[9] and it is 43 km (27 mi) long and 13 km (8 mi) wide. It is separated from Anatolia by the approximately 1-mile-wide (1.6 km) Mycale Strait. While largely mountainous, Samos has several relatively large and fertile plains.

A great portion of the island is covered with vineyards, from which muscat wine is made. The most important plains except the capital, Vathy, in the northeast, are that of Karlovasi, in the northwest, Pythagoreio, in the southeast, and Marathokampos in the southwest. The island's population is 33,814, which is the 9th most populous of the Greek islands. The Samian climate is typically Mediterranean, with mild rainy winters, and warm rainless summers.

Samos' relief is dominated by two large mountains, Ampelos and Kerkis (anc. Kerketeus). The Ampelos massif (colloquially referred to as "Karvounis") is the larger of the two and occupies the center of the island, rising to 1,095 metres (3,593 ft). Mt. Kerkis, though smaller in area is the taller of the two and its summit is the island's highest point, at 1,434 metres (4,705 ft). The mountains are a continuation of the Mycale range on the Anatolian mainland.[5]

According to Strabo, the name Samos is from Phoenician meaning "rise by the shore".

Image gallery

NASA satellite 3D view of Samos.

NASA satellite 3D view of Samos. Psalida Beach. Mount Kerketeas is in the distant background.

Psalida Beach. Mount Kerketeas is in the distant background.- View of Poseidonio.

Fauna

Samos is home to many surprising species including the golden jackal, stone marten, wild boar, flamingos and monk seal.[10]

Climate

Samos is one of the sunniest places in Europe with almost 3300 hours of sunshine annually or 74% of the day time. Its climate is mild and wet in winter and dry in summer.

| Climate data for Samos Airport, Greece | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.4 (68.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.0 (75.2) |

28.0 (82.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

39.4 (102.9) |

43.0 (109.4) |

40.6 (105.1) |

37.2 (99.0) |

31.6 (88.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

23.0 (73.4) |

43.0 (109.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.4 (56.1) |

13.7 (56.7) |

16.3 (61.3) |

19.8 (67.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.6 (92.5) |

28.6 (83.5) |

23.6 (74.5) |

18.8 (65.8) |

14.9 (58.8) |

22.7 (72.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

10.7 (51.3) |

12.8 (55.0) |

15.9 (60.6) |

20.5 (68.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

28.8 (83.8) |

28.8 (83.8) |

24.4 (75.9) |

20.0 (68.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

12.2 (54.0) |

18.8 (65.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 7.7 (45.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

21.0 (69.8) |

24.0 (75.2) |

24.1 (75.4) |

20.2 (68.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

12.1 (53.8) |

9.5 (49.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.4 (27.7) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

7.0 (44.6) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 148.5 (5.85) |

102.8 (4.05) |

85.9 (3.38) |

31.8 (1.25) |

15.5 (0.61) |

2.7 (0.11) |

0.7 (0.03) |

1.1 (0.04) |

22.7 (0.89) |

28.9 (1.14) |

110.4 (4.35) |

163.7 (6.44) |

714.7 (28.14) |

| Average precipitation days | 12.4 | 10.4 | 8.6 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 4.6 | 9.3 | 13.7 | 73.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.2 | 68.1 | 67.5 | 64.4 | 59.1 | 50.5 | 43.7 | 46.0 | 51.6 | 62.2 | 68.6 | 72.6 | 61.3 |

| Source 1: Hellenic National Meteorological Service (temperature and precipitation days)[11] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (precipitation, and extremes)[12] | |||||||||||||

History

Early and Classical Antiquity

In classical antiquity the island was a center of Ionian culture and luxury, renowned for its Samian wines and its red pottery (called Samian ware by the Romans). Its most famous building was the Ionic order archaic Temple of goddess Hera—the Heraion.[5]

Concerning the earliest history of Samos, literary tradition is singularly defective. At the time of the great migrations it received an Ionian population which traced its origin to Epidaurus in Argolis: Samos became one of the twelve members of the Ionian League. By the 7th century BC it had become one of the leading commercial centers of Greece. This early prosperity of the Samians seems largely due to the island's position near trade-routes, which facilitated the importation of textiles from inner Asia Minor, but the Samians also developed an extensive oversea commerce. They helped to open up trade with the population that lived around the Black Sea as well as with Egypt, Cyrene (Libya), Corinth, and Chalcis. This caused them to become bitter rivals with Miletus. Samos was able to become so prominent despite the growing power of the Persian empire because of the alliance they had with the Egyptians and their powerful fleet. The Samians are also credited with having been the first Greeks to reach the Straits of Gibraltar.[13]

The feud between Miletus and Samos broke out into open strife during the Lelantine War (7th century BC), with which we may connect a Samian innovation in Greek naval warfare, the use of the trireme. The result of this conflict was to confirm the supremacy of the Milesians in eastern waters for the time being; but in the 6th century the insular position of Samos preserved it from those aggressions at the hands of Asiatic kings to which Miletus was henceforth exposed. About 535 BC, when the existing oligarchy was overturned by the tyrant Polycrates, Samos reached the height of its prosperity. Its navy not only protected it from invasion, but ruled supreme in Aegean waters. The city was beautified with public works, and its school of sculptors, metal-workers and engineers achieved high repute.[5]

Eupalinian aqueduct

In the 6th century BC Samos was ruled by the famous tyrant Polycrates. During his reign, two working groups under the lead of the engineer Eupalinos dug a tunnel through Mount Kastro to build an aqueduct to supply the ancient capital of Samos with fresh water, as this was of the utmost defensive importance (since being underground, it was not easily detected by an enemy who could otherwise cut off the supply). Eupalinos' tunnel is particularly notable because it is the second earliest tunnel in history to be dug from both ends in a methodical manner.[14] With a length of over 1 km (0.6 mi), Eupalinos' subterranean aqueduct is today regarded as one of the masterpieces of ancient engineering. The aqueduct is now part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Pythagoreion.

Persian Wars and Persian rule

After Polycrates' death Samos suffered a severe blow when the Persian Achaemenid Empire conquered and partly depopulated the island. It had regained much of its power when in 499 BC it joined the general revolt of the Ionian city-states against Persia; but owing to its long-standing jealousy of Miletus it rendered indifferent service, and at the decisive battle of Lade (494 BC) part of its contingent of sixty ships was guilty of outright treachery. In 479 BC the Samians led the revolt against Persia, during the Battle of Mycale,[5] which was part of the offensive by the Delian League (led by Cimon).

Samian War

In the Delian League Samos held a position of special privilege and remained actively loyal to Athens until 440 BC when a dispute with Miletus, which the Athenians had decided against them, induced them to secede. With a fleet of sixty ships they held their own for some time against a large Athenian fleet led by Pericles himself, but after a protracted siege were forced to capitulate.[5] It was punished, but Thucydides tells us not as harshly as other states which rebelled against Athens. Most in the past had been forced to pay tribute but Samos was only told to repay the damages that the rebellion cost the Athenians: 1,300 talents, to pay back in installments of 50 talents per annum.

Peloponnesian War

During the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), Samos took the side of Athens against Sparta, providing their port to the Athenian fleet. At the end of the Peloponnesian War, Samos appears as one of the most loyal dependencies of Athens, serving as a base for the naval war against the Peloponnesians and as a temporary home of the Athenian democracy during the revolution of the Four Hundred at Athens (411 BC), and in the last stage of the war was rewarded with the Athenian franchise. This friendly attitude towards Athens was the result of a series of political revolutions which ended in the establishment of a democracy. After the downfall of Athens, Samos was besieged by Lysander and again placed under an oligarchy.[5]

In 394 BC the withdrawal of the Spartan navy induced the island to declare its independence and reestablish a democracy, but by the peace of Antalcidas (387 BC) it fell again under Persian dominion. It was recovered by the Athenians in 366 after a siege of eleven months, and received a strong body of military settlers, the cleruchs which proved vital in the Social War (357-355 BC). After the Lamian War (322 BC), when Athens was deprived of Samos, the vicissitudes of the island can no longer be followed.[5]

Famous Samians of Antiquity

Perhaps the most famous persons ever connected with classical Samos were the philosopher and mathematician Pythagoras and the fabulist Aesop. In 1955 the town of Tigani was renamed Pythagoreio in honor of the philosopher.

Other notable personalities include the philosophers Melissus of Samos and Epicurus, who were of Samian birth, and the astronomer Aristarchus of Samos, whom history credits with the first recorded heliocentric model of the solar system. The historian Herodotus, known by his Histories resided in Samos for a while.

There was a school of sculptors and architects that included Rhoecus, the architect of the Temple of Hera (Olympia), and the great sculptor and inventor Theodorus, who is said to have invented with Rhoecus the art of casting statues in bronze.

The vases of Samos were among the most characteristic products of Ionian pottery in the 6th century.

Hellenistic and Roman Eras

For some time (about 275–270 BC) Samos served as a base for the Egyptian fleet of the Ptolemies, at other periods it recognized the overlordship of Seleucid Syria. In 189 BC, it was transferred by the Romans to their vassal, the Attalid dynasty's Hellenistic kingdom of Pergamon, in Asia Minor.[5]

Enrolled from 133 in the Roman province of Asia Minor, Samos sided with Aristonicus (132) and Mithridates (88) against its overlord, and consequently forfeited its autonomy, which it only temporarily recovered between the reigns of Augustus and Vespasian. Nevertheless, Samos remained comparatively flourishing, and was able to contest with Smyrna and Ephesus the title "first city of lonia";[5] it was chiefly noted as a health resort and for the manufacture of pottery. Since Emperor Diocletian's Tetrarchy it became part of the Provincia Insularum, in the diocese of Asiana in the eastern empire's pretorian prefecture of Oriens.[5]

Byzantine and Genoese Eras

As part of the Byzantine Empire, Samos became part of the namesake theme. After the 13th century it passed through much the same changes of government as Chios, and, like the latter island, became the property of the Genoese firm of Giustiniani (1346–1566; 1475 interrupted by an Ottoman period). It was also ruled by Tzachas between 1081–1091.[5]

Ottoman rule

Samos came under Ottoman rule in 1475[15] or c. 1479/80,[16] at which time the island was practically abandoned due to the effects of piracy and the plague. The island remained desolate for almost a full century before the Ottoman authorities, by now in secure control of the Aegean, undertook a serious effort to repopulate the island.[16]

In 1572/3, the island was granted as a personal domain (hass) to Kilic Ali Pasha, the Kapudan Pasha (the Ottoman Navy's chief admiral). Settlers, including Greeks and Arvanites from the Peloponnese and the Ionian Islands, as well as the descendants of the original inhabitants who had fled to Chios, were attracted through the concession of certain privileges such as a seven-year tax exemption, a permanent exemption from the tithe in exchange for a lump annual payment of 45,000 piastres, and a considerable autonomy in local affairs.[16] The island recovered gradually, reaching a population of some 10,000 in the 17th century, which was still concentrated mostly in the interior. It was not until the mid-18th century that the coast began to be densely settled as well.[16]

Under Ottoman rule, Samos (Ottoman Turkish: سيسام Sisam) came under the administration of the Kapudan Pasha's Eyalet of the Archipelago, usually as part of the Sanjak of Rhodes rather than as a distinct province.[15] Locally, the Ottoman authorities were represented by a voevoda, who was in charge of the fiscal administration, the kadi (judge), the island's Orthodox bishop and four notables representing the four districts of the island (Vathy, Chora, Karlovasi and Marathokampos).[16] Ottoman rule was interrupted during the Russo-Turkish War of 1768–1774, when the island came under Russian control in 1771–1774.[16]

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca that concluded the war contained clauses that enabled a great expansion of the commercial activities of the Ottoman Empire's Greek Orthodox population. Samian merchants also took advantage of this, and an urban mercantile class based on commerce and shipping began to grow.[16] The Samian merchants' voyages across the Mediterranean, as well as the settlement of Greeks from the Ionian Islands (which in 1797 had passed from Venice to the French Republic), introduced to Samos the progressive ideas of the Age of Enlightenment and of the French Revolution, and led to the formation of two rival political parties, the progressive-radical Karmanioloi ("Carmagnoles", named after the French Revolutionary song Carmagnole) and the reactionary Kallikantzaroi ("goblins") who represented mostly the traditional land-holding elites. Under the leadership of Lykourgos Logothetis, in 1807 the Karmanioloi gained power in the island, introducing liberal and democratic principles and empowering the local popular assembly at the expense of the land-holding notables. Their rule lasted until 1812, when they were overthrown by the Ottoman authorities and their leaders expelled from the island.[16]

Greek Revolution

In March 1821, the Greek War of Independence broke out, and on 18 April, under the leadership of Logothetis and the Karmanioloi, Samos too joined the uprising. In May, a revolutionary government with its own constitution was set up to administer the island, mostly inspired by Logothetis.[17]

The Samians successfully repulsed three Ottoman attempts to recapture the island: in summer 1821, in July 1824, when Greek naval victories off Samos and at Gerontas averted the threat of an invasion, and again in summer 1826. In 1828, the island became formally incorporated into the Hellenic State under Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias, as part of the province of the Eastern Sporades, but the London Protocol of 1830 excluded Samos from the borders of the independent Greek state.[17]

The Samians refused to accept their re-subordination to the Sultan, and Logothetis declared Samos to be an independent state, governed as before under the provisions of the 1821 constitution. Finally, due to the pressure of the Great Powers, Samos was declared an autonomous, tributary principality under Ottoman suzerainty. The Samians still refused to accept this decision until an Ottoman fleet enforced it in May 1834, forcing the revolutionary leadership and a part of the population to flee to independent Greece, where they settled near Chalkis.[17]

Autonomous Principality

.svg.png)

In 1834, the island of Samos became the territory of the Principality of Samos, a semi-independent state tributary to Ottoman Turkey, paying the annual sum of £2,700. It was governed by a Christian of Greek descent though nominated by the Porte, who bore the title of "Prince." The prince was assisted in his function as chief executive by a 4-member senate. These were chosen by him out of eight candidates nominated by the four districts of the island: Vathy, Chora, Marathokampos, and Karlovasi. The legislative power belonged to a chamber of 36 deputies, presided over by the Greek Orthodox Metropolitan. The seat of the government was the port of Vathý.[5]

The modern capital of the island was, until the early 20th century, at Chora, about 2 miles (3.2 km) from the sea and from the site of the ancient city.[5]

After reconsidering political conditions, the capital was moved to Vathy, at the head of a deep bay on the North coast. This became the residence of the prince and the seat of government.[5]

Since then a new town has grown, with a harbour.

Modern era

The island was united with the Kingdom of Greece in 1913, a few months after the outbreak of the First Balkan War. Although other Aegean islands had been quickly captured by the Greek Navy, Samos was initially left to its existing status quo out of a desire not to upset the Italians in the nearby Dodecanese. The Greek fleet landed troops on the island on 13 March 1913. The clashes with the Ottoman garrison were short-lived as the Ottomans withdrew to the Anatolian mainland, so that the island was securely in Greek hands by 16 March.[18][19]

During World War II, the island was occupied by the Italians from May 1941 until the Italian surrender in September 1943. Samos was briefly taken over by Greek and British forces on 31 October, but following the Allied defeat in the Battle of Leros and a fierce aerial bombardment, the island was abandoned on 19 November and taken over by German troops. The German occupation lasted until 4 October 1944, when the island was liberated by the Greek Sacred Band.

On August 3, 1989, a Short 330 aircraft of the Olympic Airways (now Olympic Airlines) crashed near Samos Airport; 31 passengers and the crew died.[20]

Government

Samos is a separate regional unit of the North Aegean region, and the only municipality of the regional unit. As a part of the 2011 Kallikratis government reform, the regional unit Samos was created out of part of the former Samos Prefecture. At the same reform, the current municipality Samos was created out of the 4 former municipalities:[21]

Samos has a sister town called Samo, which is located in Calabria, Italy.

Economy

The Samian economy depends mainly on agriculture and the tourist industry which was growing steadily since the early 1980s and reached a peak at the end of the 1990s.[23] The main agricultural products include grapes, honey, olives, olive oil, citrus fruit, dried figs, almonds and flowers. The Muscat grape is the main crop used for wine production. Samian wine is also exported under several other appellations.

Cuisine

Local specialities:

- Bourekia (Börek)

- Katimeria

- Armogalo cheese

- Katádes (dessert)

- Moustalevria (dessert)

- Muscat of Samos (wine)

- Tiganites

UNESCO

The island is the location of the joint UNESCO World Heritage Sites of the Heraion of Samos and the Pythagoreion which were inscribed in UNESCO's World Heritage list in 1992.[24]

Notable people

Ancient

- Aegles, athlete

- Aeschrion of Samos, poet

- Aesop, storyteller

- Aethlius (writer)

- Agatharchus, painter

- Agathocles (writer)

- Aristarchus of Samos (3rd century BC), astronomer and mathematician, the first known individual to propose that the Earth revolves around the sun

- Asclepiades of Samos, epigrammist and poet

- Asius of Samos, poet

- Conon of Samos, astronomer and mathematician

- Creophylus of Samos, legendary singer

- Duris of Samos (4th-3rd century BC), historian

- Epicurus (4th century BC), philosopher, founder of the Epicurean school of philosophy

- Melissus of Samos, philosopher

- Nicaenetus of Samos, poet

- Philaenis (4th-3rd century BC), courtesan and writer

- Polycrates (6th century BC), tyrant of Samos

- Pythagoras (6th century BC), philosopher, mathematician, and religious leader, after whom the Pythagorean theorem is named ('the square on the hypotenuse of a right-angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides')

- Telauges, philosopher

- Pythagoras (sculptor)

- Rhoecus (6th century BC), sculptor

- Telesarchus of Samos (6th century BC), aristocrat

- Theodorus (6th century BC), sculptor and architect

- Theon of Samos, painter

Modern

- Lykourgos Logothetis (1772–1850), leader of the Samians during the revolution of 1821

- Ion Ghica (1816–1897), Romanian revolutionary, mathematician, diplomat, prime minister of Romania, first president of the Romanian Academy, prince of Samos

- Themistoklis Sofoulis (1860–1949), politician and PM of Greece

- Kostas Roukounas (1903-1984), singer of Rebetika

- Nikos Stavridis (1910–1987), actor

- Nerses Ounanian (1924-1957), Armenian-Uruguayan sculptor

Gallery

The town hall and the archaeological museum in Vathy

The town hall and the archaeological museum in Vathy St Spyridon, Samos town

St Spyridon, Samos town Old tobacco factory, Samos town

Old tobacco factory, Samos town- Kokkari beach

Notes

- "Samos". Lexico UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Samos". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Samos". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- "Samos". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Bunbury, Caspari & Gardner 1911, p. 116.

- Everett-Heath, John (2017). The Concise Dictionary of World Place Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780192556462.

- Marozzi, Justin (2010-02-02). The Way of Herodotus: Travels with the Man Who Invented History. ISBN 9780786727278.

- Leaf, Walter (2010). Homer, the Iliad. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108016872.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-21.

- "Conservation Action Plan for the golden jackal (Canis aureus) in Greece" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-10. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- "Samos Climate". Hellenic National Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on 19 December 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Climate Data for Samos". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- "Samos (island, Greece) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

- The Siloam Tunnel was first Archived 2011-03-22 at the Wayback Machine

- Birken, Andreas (1976). Die Provinzen des Osmanischen Reiches. Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients (in German). 13. Reichert. p. 107. ISBN 9783920153568.

- Landros Christos; Kamara Afroditi; Dawson Maria-Dimitra; Spiropoulou Vaso (10 July 2005). "Samos: 2.3. Ottoman rule". Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago. Foundation of the Hellenic World. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Landros Christos, Kamara Afroditi; Dawson Maria-Dimitra; Spiropoulou Vaso (10 July 2005). "Samos: 2.4. The Greek War of Independence, 1821". Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago. Foundation of the Hellenic World. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Hall, Richard C. (2000). The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913: Prelude to the First World War. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 0-415-22946-4.

- Erickson, Edward J. (2003). Defeat in Detail: The Ottoman Army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 158–159. ISBN 0-275-97888-5.

- ASN Aircraft Accident Shorts 330-200 SX-BGE

- "Kallikratis reform law text" (PDF).

- "Detailed census results 1991" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-03. (39 MB) (in Greek and French)

- Ioannis Spilanis, H. Vayanni et K. Glyptou (2012). Evaluating the tourism activity in a destination: the case of Samos Island, Revue Etudes Caribéennes, http://etudescaribeennes.revues.org/6257

- "Pythagoreion and Heraion of Samos - UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. 2009-09-18. Archived from the original on 29 November 2005. Retrieved 2012-11-07.

References

- Attribution

![]()

Further reading

- Ancient sources

- Herodotus, especially book iii.

- Strabo xiv. pp. 636–639

- Thucydides, especially books i. and viii.

- Xenophon, Hellenica, books i. ii.

- Modern texts

- A. Agelarakis, "Anthropologic Results: The Geometric Period Necropolis at Pythagoreion". Archival Report. Samos Island Antiquities Authority, Greece, (2003).

- J. P. Barron, The Silver Coins of Samos (London, 1966).

- J. Boehlau, Aus ionischen and italischen Nekropolen (Leipzig, 1898). (E. H. B.; M. 0. B. C.; E. Ga.).

- C. Curtius, Urkunden zur Geschichte von Samos (Wesel, 1873).

- P. Gardner, Samos and Samian Coins (London, 1882).

- V. Guérin, Description de l'île de Patmos et de l'île de Samos (Paris, 1856).

- K. Hallof and A. P. Matthaiou (eds), Inscriptiones Chii et Sami cum Corassiis Icariaque (Inscriptiones Graecae, xii. 6. 1–2). 2 vols. (Berolini–Novi Eboraci: de Gruyter, 2000; 2004).

- B. V. Head, Historia Numorum (Oxford, 1887), pp. 515–518.

- L. E. Hicks and G. F. Hill, Greek Historical Inscriptions (Oxford, 1901), No. 81.

- H. Kyrieleis, Führer durch das Heraion von Samos (Athen, 1981).

- T. Panofka, Res Samiorum (Berlin, 1822).

- Pauly-Wissowa (in German, on Antiquity)

- T. J. Quinn, Athens and Samos, Chios and Lesbos (Manchester, 1981).

- G. Shipley, A History of Samos 800–188 BC (Oxford, 1987).

- R. Tölle-Kastenbein, Herodot und Samos (Bochum, 1976).

- H. F. Tozer, Islands of the Aegean (London, 1890).

- K. Tsakos, Samos: A Guide to the History and Archaeology (Athens, 2003).

- H. Walter, Das Heraion von Samos (München, 1976).

- Westermann, Großer Atlas zur Weltgeschichte (in German)

- Volumes of the Samos series of archaeological reports published by the Deutsches Archäologisches Institut.

- 1. V. Milojčić, Die prähistorische Siedlung unter dem Heraion (Bonn, 1961).

- 2. R. C. S. Felsch, Das Kastro Tigani (Bonn, 1988).

- 3. A. E. Furtwängler, Der Nordbau im Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1989).

- 4. H. P. Isler, Das archaische Nordtor und seine Umgebung im Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1978).

- 5. H. Walter, Frühe samische Gefäße (Bonn, 1968).

- 6.1. E. Walter-Karydi, Samische Gefäße des 6. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. (Bonn, 1973).

- 7. G. Schmidt, Kyprische Bildwerke aus dem Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1968).

- 8. U. Jantzen, Ägyptische und orientalische Bronzen aus dem Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1972).

- 9. U. Gehrikg, with G. Schneider, Die Greifenprotomen aus dem Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 2004).

- 10. H. Kyrieleis, Der große Kuros von Samos (Bonn, 1996).

- 11. B. Freyer-Schauenburg, Bildwerke der archaischen Zeit und des strengen Stils (Bonn, 1974).

- 12. R. Horn, Hellenistische Bildwerke auf Samos (Bonn, 1972).

- 14. R. Tölle-Kastenbein, Das Kastro Tigani (Bonn, 1974).

- 15. H. J. Kienast, Die Stadtmauer von Samos (Bonn, 1978).

- 16. W. Martini, Das Gymnasium von Samos (Bonn, 1984).

- 17. W. Martini and C. Streckner, Das Gymnasium von Samos: das frühbyzantinische Klostergut (Bonn, 1993).

- 18. V. Jarosch, Samische Tonfiguren aus dem Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1994).

- 19. H. J. Kienast, Die Wasserleitung des Eupalinos auf Samos (Bonn, 1995).

- 20. U. Jantzen with W. Hautumm, W.-R. Megow, M. Weber, and H. J. Kienast, Die Wasserleitung des Eupalinos: die Funde (Bonn, 2004).

- 22. B. Kreuzer, Die attisch schwarzfigurige Keramik aus dem Heraion von Samos (Bonn, 1998).

- 24.1. T. Schulz with H. J. Kienast, Die römischen Tempel im Heraion von Samos: die Prostyloi (Bonn, 2002).

- 25. C. Hendrich, Die Säulenordnung des ersten Dipteros von Samos (Bonn, 2007).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Samos Island. |

- Prefecture of Samos

- Municipality of Vathy - The capital of Samos

- World Statesmen - Greece

- Visit Samos