Mycale

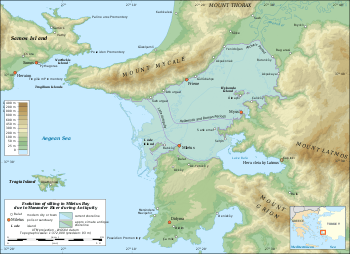

Mycale (/ˈmɪkəli/). also Mykale and Mykali (Ancient Greek: Μυκάλη, Mykálē), called Samsun Dağı and Dilek Dağı (Dilek Peninsula) in modern Turkey, is a mountain on the west coast of central Anatolia in Turkey, north of the mouth of the Maeander and divided from the Greek island of Samos by the 1.6 km wide Mycale Strait. The mountain forms a ridge, terminating in what was known anciently as the Trogilium promontory (Ancient Greek Τρωγίλιον or Τρωγύλιον).[1] There are several beaches on the north shore ranging from sand to pebbles. The south flank is mainly escarpment.

| Mount Mycale | |

|---|---|

| Μυκάλη Samsun Daği | |

The flanks of Mycale behind Priene | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,237 m (4,058 ft) at Dilek Tepesi, the high point; 600 metres (1,969 ft) average |

| Coordinates | 37°40′N 27°05′E |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Samson's Mountain |

| Language of name | Turkish language |

| Geography | |

Mount Mycale Aydin Province, Republic of Turkey | |

| Parent range | Aydin Mountain Range in the Menderes Massif |

| Geology | |

| Mountain type | Ridge, 200 kilometres (124 mi) long |

| Climbing | |

| Easiest route | Hike |

In classical Greece nearly the entire ridge was a promontory enclosed by the Aegean Sea. Geopolitically it was part of Ionia with Priene placed on the coast on the south flank of the mountain and Miletus on the coast opposite to the south across the deep embayment into which the Maeander River drained. Somewhat further north was Ephesus.

The ruins of the first two Ionian cities mentioned with their harbor facilities remain but today are several miles inland overlooking instead a rich agricultural plain and delta parkland created by deposition of sediments from the river, which continues to form the geological feature named after it, maeanders. The end of the former bay remains as a lake, Çamiçi Gölü (Lake Bafa). Samsun Daği, or Mycale, still has a promontory.

The entire ridge was designated as a national park in 1966; Dilek Yarimadisi Milli Parki ("Dilek Peninsula National Park") has 109.85 square kilometres (27,145 acres), which is partly accessible to the public. The remainder is a military reservation. The park's isolation has encouraged the return of the native ecology, which is 60% maquis shrubland. It is a refuge for species that used to be more abundant in the region.

Geophysics

Western Turkey is mainly fault-block terrain, with steep-sided ridges running east-west and rivers in the rifts. The source of the faulting is the closing of Tethys Sea and the collision of the African and Arabian plates with the Eurasian plate. The smaller Turkish and Aegean plates are being pushed together, generating ridges in Turkey. This orogenic belt was in place by 1.6 mya and continues to be a hot spot of earthquakes and volcanoes.[2]

Mount Mycale is part of a larger ridge, which continues in Samos on the other side of the Samos Strait, and to the northeast in the Aydin Dağlari ("Aydin Mountains"), ancient Messogis range, on the other side of low hills and passes. The entire block of mountains around the Menderes (Maeander) River is known as the Menderes Massif.[3]

Mycale is scored transversely by numerous ravines through which sources drain. The biggest ravine is Oluk Gorge, with cliffs 200 metres (656 ft) high. The main permanent streams are the Bal Deresi, the Sarap Dami and the Oluk Dereleri. The ample water supply supports a verdant maquis.

The rock is primarily metamorphic: marble and limestone formed from rocks originating in the Mesozoic,crystalline schists formed from rocks originating in the Palaeozoic and conglomerates of the Cenozoic. The renowned builders and sculptors of Ionia made full use of these materials for their major works.

Ecology

The ridge and its environs offer a number of different ecologies. The crest is a sharp divide between the xerophytic southern slopes and the forested northern slopes, with 66.24 square kilometres (16,368 acres) of maquis and 35.74 square kilometres (8,832 acres) of mixed pine.[4] Around the base of the promontory is a maritime environment.

The maquis vegetation includes Pistacia lentiscus; Laurus nobilis; Quercus ilex, Q. frainetto and Q. ithaburensis; Phillyrea latifolia; Ceratonia siliqua; Olea europaea; Rubus fruticosus; Myrtus communis; Smilax; Jasminum fruticans; Vitex vivifera; Lathyrus grandiflorus; Erica arborea; and Juncus on the slopes of the north. In moister areas are to be found Nerium oleander, Platanus orientalis, Fraxinus ornus, Laurus nobilis, Cupressus sempervirens and Rubus fruticosus.

The mixed pine forest goes up to 700 metres (2,297 ft). Its major plant species are Pinus brutia, Juniperus phoenicea, with broad-leaved trees and shrubs: Ulmus campestris, Acer sempervirens, Fraxinus ornus, Castanea sativa, Tilia platyphyllos, Sorbus torminalis, Viburnum tinus, Pyrus eleagrifolia and Prunus dulcis.

Some mammals native to the region are Sus scrofa, Vulpes vulpes, Hystrix cristata, Canis aureus, Canis lupus, Martes martes, Lynx lynx, Felis sylvestris, Ursus arctos, Meles meles, Lepus, Erinaceus europaeus and Sciurus. Migrants are Lynx caracal and Panthera pardus.

Some birds are Columba livia, Alectoris graeca, Perdix perdix, Coturnix coturnix, Scolopax rusticola, Turdus merula, Turdus pilaris, Oriolus oriolus, Merops apiaster, eagles, vultures, Corvus corax, Pica pica and Sturnus vulgaris.

Monachus monachus breeds in caves around the shores of Mycale. They and other marine predators (including man) feed on Liza, Pagellus, Dentex vulgaris and Thunnus thynnus.

History

Earliest references

Mycale, Miletus and the Maeander appear in the Trojan Battle Order of the Iliad, where they are populated by Carians. "The steep heights of Mycale" and Miletus are also in the Hymn to Apollo, where Leto, pregnant with Apollo, an especially Ionian god, travels about the Aegean looking for a home for her son, and settles on Delos, the major Ionian political, religious and cultural center of Classical Greece.

A similar metaphor is to be found in the centuries-later Hymn to Delos of Callimachus, in which Delos, a swimming island, visits various places in the Aegean, including Parthenia, "Maiden's Isle" (Samos), where it is entertained by the nymphs of Mycalessos. Just as Parthenia is the previous name of Samos so the reader is to understand Mycalessos as the previous name of Mycale. On being chosen as the birthplace of Apollo, Delos becomes fixed in the sea.

There are no earlier instances of Mycale but some major Creto-Mycenan cities, later Ionian, which appear in Mycenaean Greek and Hittite records of the Late Bronze Age. In Hitti language, there were the Achaean-Greek cities Apasa (Ephesus), the capital of a state called Arzawa, in which also was Karkisha in (Caria) and Millawanda (Miletus). In the Linear B script tablets the region is called A-swi-ja (Asia). Documents at Pylos, Thebes and Knossos identify female textile workers and seamstresses (raptria)in servitude of Mi-ra-ti-ja, *Milātiai, "Milesians." The regions from which they came were centers of Mycenaean civilization although the languages they spoke was an early Greek-Mycenaean language and written in Linear B, although some support that was an unknown.[5]

The state of Melia

After the Late Bronze Age the entire Aegean region entered a historical period termed the Greek Dark Ages. Archaeologically it was known as the Proto-geometric and Geometric Periods, which did not belong to any one ethnic group. This is the time to which heavy Ionic migration from mainland Greece to the coast of Ionia and the emergence of Delos as an Ionian center is believed to apply. These events were over at the start of the brilliant renaissance of the Orientalizing Period in which Ionia played a cardinal role.

During this rise to prominence twelve cities were settled or resettled and emerged as Ionia speaking varieties of Ionic Greek. Vitruvius, however, says there were thirteen, the extra state being Melite, which "... as a punishment of the arrogance of its citizens was detached from the other states in a war levied pursuant to the directions of a general council (communi consilio); and in its place ... the city of Smyrna was admitted into the number of Ionian states (inter Ionas est recepta)."[6] There is no other mention of Melite anywhere but two fragments of Hecataeus say that Melia was a city of Caria and an inscription from Priene confirms that there had been a "Meliac War"[7] against a state located between Priene and Samos; i.e., on Mycale.

The inscription records the result of an arbitration between Priene and Samos by jurors from Rhodes. Both litigants claimed that Carium, the fortified settlement of Melia, and Dryussa, another settlement, had been distributed to them at the conclusion of the Meliac War, when the Carians were expelled.[8] Being on the Samian side of the crest Melia had been resettled mainly by Samians and for this reason they had won a similar case brought before Lysimachus of Macedon a century earlier. That case is mentioned in an earlier inscription from Priene.[9]

Priene had now reopened the case arguing that their sale of plots from the land demonstrated their continuous ownership of it except for a brief period when an invasion of the Cimmerians under Lygdamus forced temporary Greek evacuation of the region (about 650 BC). The Samians used a passage from the now missing History of Maeandrius of Miletus to support their claim. The jury found that Maeandrius was not authentic and reversed the earlier decision.[10]

Panionium

The Melians had named their capital Carium, "of Caria" as a Greek word. Considering that it was placed in Ionia, the choice of name suggests a political statement of some sort, although the word may have had a different meaning in the Carian language, now lost except for a few dozen words. The Ionians leagued together to defeat it and continued the league, building a capital they called Panionium, "of all the Ionians" next to the former Carium. It rose to prominence while the Ionian confederacy was sovereign, became a memory when Ionia was incorporated into other states and empires and finally was lost altogether. The ancient writers remembered that it had been on the north side of the mountain, across the ridge from Priene.

After a few false identifications in modern times, the ruins of Melia and the Panionium were discovered in 2004 on Dilek Daglari, a smaller peak of Mycale, 15 kilometres (9 mi) to the north of Priene at an elevation of 750 metres (2,461 ft).[11] The Carium must be the early 7th century BC town surrounded by a triangular wall in places as thick as 3 metres (10 ft).

The floruit was the early 7th, but sherds have been found there from as early as the Protogeometric period. Coldstream characterizes the burial structures as of "a considerable Carian substrate."[12] The culture was not entirely Carian; the Ionians continued the worship of Poseidon Heliconius there, which Strabo says came from Helike in Peloponnesian Achaea.[13] This event must have been during the Ionian colonization. Melia therefore was a renegade Ionian state.

The temple believed to the Panionium was constructed next to the Carium about 540 BC.[11] It took over the worship of Poseidon Heliconius, served as the meeting place of the Ionian League, and was the site of the religious festival and games (panegyris) called the Panionia. The construction of this temple is a terminus post quem for the existence of the Ionian League, which as a constituted body had a name, the koinon Iōnōn ("common thing of the Ionians"), a synedrion ("place to sit down together") and a boulē ("council").

Whether this body existed before the Meliac War is uncertain. Vitruvius' commune consilium seems to translate koinon. Some analysts have postulated an association as early as 800 BC but whether formally constituted remains unknown. There is no sign of it yet on Mycale unless Carium had in fact been it.

Battle of Mycale

In 479 BC, Mycale was the site of one of the two major battles that ended the second Persian invasion of Greece, during the Greco-Persian Wars. Under the leadership of the Spartan Leotychides, the Greek fleet defeated the Persian fleet and army.[14] According to Herodotus, the battle occurred the same day as the Greek victory at Plataea.[15]

Notes

- Smith, William (1850). "Mycale". New Classical Dictionary of Biography, Mythology and Geography. London: John Murray.. Downloadable Google Books.

- Metz, Helen Chapin (Editor) (1995). "Geology". Turkey: A Country Study. GPO for the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-01-30.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Candan, Osman; O. Özcan Dora (February 1998). "Granulite, eclogite and blueschist relics in the Menderes Massif: an approach to pan-African and tertiary metamorphic evolution" (PDF). Geological Bulletin of Turkey. 41 (1): 3.

- UNEP:WCMC (1988). "Turkey: Dilek Yarimadisi NP (Dilek Peninsula)". United Nations Environment Programme: World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Archived from the original on 2008-02-21. Retrieved 2008-02-01.

- Morris, Sarah (2000). "Potnia Aswiya: Anatolian Contributions to Greek Religion". In Laffineur, Robert; Hägg, Robin (eds.). Potnia: Deities and Religion in the Aegean Bronze Age: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference Göteborg. Université de Liège: Aegeum 22 2001. pp. 425–428. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2008-02-05..

- Vitruvius, Marcus (2008). Thayer, Bill (ed.). de Architectura: Book IV Chapter 1 Sections 4-5. LacusCurtius..

- Often called a Melian War but the latter should not be confused with the later war of Athens against the island of Melos.

- Syll. 599 - in English translation.

- RC. 7 - in English translation.

- A discussion of the arbitration in English can be found at Tod, Marcus Niebuhr (1913). International Arbitration Amongst the Greeks. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. pp. 135–140. Downloadable Google Books. Most of the inscription can be found in Müller, Carolus (1848). Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum: Volumen Secundum (in Greek and Latin). Paris: Editore Ambrosio Firmin Didot. pp. 336–337, Fragment 7, Maeandrii Milesii. Downloadable Google Books.

- Editors (2005). "Recent Finds in Archaeology: Panionion Sanctuary Discovered in Southwest Turkey". Athena Review. 4 (2): 10–11. Archived from the original on 2012-03-23. Retrieved 2008-02-02.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Coldstream, John Nicolas (2003). Geometric Greece: 900-700 BC: Second Edition. London, New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. p. 97. ISBN 0-415-29898-9.

- Pausanias (2000–2008). "Description of Greece 7.24.5". Theoi Greek Mythology: Poseidon Cult 2: II Helike Town in Akhaia. The Theoi Project: Greek Mythology. Retrieved 2008-08-02. Strabo's contention (8.7.2, quoted on same page) that the "Akhaians later gave the model of the temple to the Ionians" cannot be true, as the submersion did not occur until 373 BC.

- Pausanias, 1.25.1, 3.7.9, 8.52.3; Thucydides, 1.89.

- Herodotus, 9.90, 9.96.

References

- Herodotus, Histories, A. D. Godley (translator), Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1920; ISBN 0-674-99133-8 .

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, (Loeb Classical Library) translated by W. H. S. Jones; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. (1918) ; Vol 2, Books III–V, ISBN 0-674-99207-5; Vol 3, Books VI–VIII.21, ISBN 0-674-99300-4.

- Thucydides, The Peloponnesian War. London, J. M. Dent; New York, E. P. Dutton. 1910. .

External links

- Lendering, Jona (1996–2008). "Mycale (Dilek Dagi)". Livius articles on ancient history. Archived from the original on 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "Aegean and Western Turkey sclerophyllous and mixed forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2008-01-31.