Mobile learning for refugees

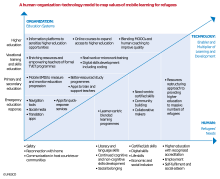

Mobile learning for refugees refers to solutions and roles that mobile technology plays in refugees’ informal learning. Educational responses ensures that refugees and displaced populations have access to equitable and inclusive quality education and lifelong learning opportunities.[1] The increased access that refugees have to digital mobile technologies is a source of support for education delivery, administration and support services in refugee contexts.[1]

Background

65 million individuals who were forcibly displaced worldwide in 2016 due to persecution, conflict, violence or human rights violations is the highest since the end of the Second World War.[2] Of this number, 22.5 million persons were Refugees who fled their country to seek protection elsewhere. In recent years, the significance of the crisis has fuelled the demand to harness digital technology to improve learning and teaching in refugee and displacement contexts.[1]

Efforts have been made to leverage mobile learning to counteract the negative repercussions of displacement on education access and attainment, as well as to build foundations for peace, stability and future prosperity. By leveraging mobile solutions, refugees can have inclusive and equitable access to quality education and lifelong learning opportunities.[1]

The role of education

Long-term approaches to education delivery in contexts with displaced populations are needed for refugees to have access to equitable and inclusive quality education and lifelong learning opportunities. In addition to traditional humanitarian support focusing on refugees’ physical needs, it is important to incorporate the integral social and community development of refugees and other displaced people, as well as to address their aspirations, ideas and dreams through education, regardless of their context.[1]

Education is an important factor that can help refugee communities realize a brighter future and integrate in hosting societies. In the short term, education can bring stability to disrupted lives, address the psychosocial needs of children, youth and entire communities, and help refugees in developing much-needed language and literacy skills.[1]

Education has also been positioned as one of the primary drivers to realize the Education 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4 aims to ‘ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all’ by the year 2030.[1] This encompasses refugees, who are among disadvantaged groups when it comes to access to quality education.[1]

Relevance of mobile technology

Today, about 86% of the world's refugees reside in developing countries, and 71% of refugee households own a mobile phone. While 39% of households have internet-enabled phones, the remaining 61% cannot benefit from applications developed for smartphones. The majority (93%) live in places covered by a 2G mobile network, and 62% are in reach of 3G mobile networks.[3]

Despite disparities between urban and rural in mobile phone ownership and network access, mobile media remain relevant to refugees because they help connect displaced people with loved ones and friends at home, on the journey to be resettled, and once they reach their host countries.[1]

The use of information and communication technology (ICT) for educational purposes in refugee contexts is still an emerging field of practice and research. Studies highlight the potential value of ICTs in crisis settings, they also show the lack of scientific evidence.[1]

Mobile learning to address individual challenges

During flight, encampment and resettlement, refugees are confronted with a number of individual challenges that can negatively impact their learning and teaching opportunities, as well as their lives beyond the learning environment.[1]

Lack of language and literacy skills in host countries

Lack of the language skills required in host settings is a challenge for refugees. Mobile-assisted language learning apps are promoted as key tools for language learning and support refugees' language and literacy skills development.[1] Mobile solutions can provide support for refugees’ language and literacy challenges in three main areas:

- Literacy development;

- Foreign-language learning;

- Translations.

Trauma and identity struggles

Refugees have reduced levels of well-being and a high prevalence of mental distress due to past and ongoing trauma.[4][5] Groups that are particularly affected and whose needs often remain unmet are women, older people and unaccompanied minors.[1]

Psychosocial well-being can be related to learning and education in two ways. First, there is evidence that refugees’ experience of war and conflict directly and negatively impacts their education and academic performance. For example, a high prevalence of academic problems and behavioral difficulties has been identified in war-affected refugee children[6] and refugees’ emotional problems have been associated with learning difficulties and lower levels of academic achievement.[7] Second, participation in school and specific education interventions can improve psychosocial well-being.[1]

Although addressing trauma and identity struggles is not at the core of many mobile learning and refugee projects, the way that digital technologies are designed and used shows potential impact of these technologies on refugees’ well-being and mental health.[1] The use of digital technology and mobile solutions cannot fully replace intensive and specialized face-to-face care in severe trauma cases in crisis and refugee contexts. However, mobile approaches have been tied to enhance refugees’ well-being. For example, digital and mobile storytelling is helpful for refugees to promote reflection on identity and sense of belonging.[1]

Studies show that the potential of mobile learning apps and programmes to support not only knowledge and skills acquisition but also enhance refugees’ psychological well-being, is relevant for educators working with refugees.[1]

Disorientation in new environments

Refugees need to adjust to new and changing environments, especially before or during transition and upon arrival.[1] During crises and in escape situations there is insufficient trust and timely information, which refugees need to navigate through insecure and unstable environments with high levels of misinformation.[1] For example, a key challenge by refugees from Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq during their journey to Europe was confirming whether certain border crossings were open or closed.[8]

Refugees often resort to unreliable social network channels before, during and after their journey, and may be exposed to the risk of being exploited by smugglers and other criminals. Access to credible information sources is critical for women and children, who are particularly vulnerable in regard to health and safety. During the journey, access to reliable information can make the difference between life and death, such as in boat situations.[9]

Informal mobile communication can serve as the main information reservoir for refugees planning their flight route. Refugees source information by communicating with others who left before, to follow their paths and learn from their experiences. They see instant messaging tools, such as WhatsApp, as a means to ‘demystify’ the journey.[10] Mobile technologies also facilitate the sharing of image-based information relevant to flight. During the journey, Mobile phones are the refugees’ lifeline, enabling them to navigate through unknown geographical and linguistic terrain by using online and offline apps and digital translation aids.[1]

Exclusion and isolation

Feelings of isolation and exclusion are a key challenge that refugees face when they move to a new environment. Experiences of loneliness not only impact refugee learners’ success in formal education but also deprive them of the much-needed networks and communities that facilitate informal learning and knowledge exchange.[1]

In refugee populations, isolation can play out in two ways. First, many refugees are separated from families and friends. Second, feelings of isolation and exclusion are aggravated by a lack of interaction with people in the mainstream culture of the host environment, especially if refugees reside in camps in isolated parts of the host country. Communication with friends and family is important to refugees, mobile technology is key to this.[1]

Refugees and migrants create mobile learning networks with their transnational families and friends. These are essential as a source for sharing tacit knowledge and stimulating feelings of proximity and mutual awareness.[1]

Mobile learning to address education system challenges

Some of the education-related challenges facing refugees transcend individual experiences, education levels and domains, and comes from issues in the education system. Such challenges include; teachers who are unprepared for education for refugees, a scarcity of appropriate learning and teaching resources, and undocumented and uncertified educational progress.[1]

Teachers unprepared for education for refugees

Teachers are important in the provision of equitable and inclusive quality education for Refugees and displaced people. They address children's physical and cognitive needs and facilitate their psychosocial well-being and serve as a key resource in achieving normality.[11] Teachers who work with refugees operate in different settings and can have different backgrounds. They could be trained/certified teachers who are refugees themselves, or teachers who are refugees but have no prior teaching experience and are trained out of necessity. They could also be teachers in host settings who work with refugees in their classrooms. The challenges associated with the preparedness of teachers to work in settings with refugees are varied.[1]

Qualified teachers are a highly demanded but rare resource across all levels and domains of education for refugees. This translates into large class sizes and high student/teacher ratios. Although the 2010–2012 UNHCR Education Strategy sets the goal of a maximum of 40 students per single teacher,[12] many refugee contexts have larger class sizes. With a global rise of 30% in 2014, the increasing number of school-age refugees exacerbates the issue of availability of qualified teachers. At least 20,000 additional teachers and 12,000 additional classrooms would be needed on a yearly basis.[3]

In addition to basic qualifications, teachers need specific training to prepare them to address the particular needs and challenges that refugees bring into the classroom.

Mobile solutions and devices can contribute to enhanced educational efficiency by supporting teachers in developing and applying an array of Skills in the classroom. Mobile learning can be used to provide mentoring and ongoing support to teachers. Additionally, some lessons can be learned from other teacher training initiatives in low-resource settings that incorporate basic technologies.[1]

Scarcity of appropriate learning and teaching resources

In refugee contexts, limited access to teaching and learning materials can exacerbate the challenges faced by teachers, who often do not have adequate training and support to meet the needs of refugee learners. When refugee learners do not have access to educational materials at school or in their homes, the process of adapting to their new learning environment become more difficult. An example is the situation of Sudanese refugee children in Chad. Due to a lack of desks, many children sit on mats on the ground while the teacher, who is the only person with a textbook, writes notes on the blackboard.[13]

In addition to physical materials, relevant curricula is needed. Many curricula have limited relevance for refugee learners’ particular situations and backgrounds. Sometimes the problem is not the lack of learning materials but their political nature. In many areas, curricula and learning resources are biased toward one side of a conflict, that could reinforce stereotypes or worsen political and social grievances. Host country teachers are often not familiar with the curricula or contexts of refugee students’ home countries.[1]

The development of new content, as well as the evaluation, selection and adaptation of existing content, is challenging in many mobile learning projects in refugee settings. The content platforms currently used in education for refugees range from static library repositories, digitized reference Books and online Encyclopedias, to multimedia platforms with levels of interactivity and monitoring features to track student progress.[1]

Many open and available educational resources is in English, therefore there is an unmet need for materials in local languages as well as content that is tailored to local curricula or matched with international teaching standards.[1]

Undocumented and uncertified educational progression

Education data at the individual, school and system levels are sometimes poorly documented, and make it difficult to obtain nationwide overviews of statistics. Missing, incomplete or low-quality information impedes the capacity of ministries of education and development organizations to rebuild, plan and manage education programmes involving refugees.[1]

At the system level, lack of information poses challenges in planning, operating and monitoring educational programmes and entire education systems. On an individual level, the lack of data, especially regarding students’ prior educational attainments and certificates obtained, restricts or destroys refugees’ chances of continuing their educational trajectories as they move from one place to another.[1]

Developing and implementing simple and flexible information systems to ensure the availability and use of quality data through education management information systems (EMISs) is need to strengthen systems in emergency settings.[1]

See also

References

![]()

- UNESCO (2018). A Lifeline to learning: leveraging mobile technology to support education for refugees. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-100262-5.

- UNHCR (19 June 2017). "Figures at a Glance".

- UNHCR (September 2016). Connecting Refugees: How Internet and Mobile Connectivity Can Improve Refugee Well-Being and Transform Humanitarian Action. Geneva, Switzerland: UNHCR. p. 12.

- Brown, J., Miller, J. and Mitchell, J (2006). "Interrupted schooling and the acquisition of literacy: experiences of Sudanese refugees in Victorian secondary schools". Australian Journal of Language and Literacy. 29 (2): 150–62.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Porter, M. and Haslam, N (2005). "Predisplacement and postdisplacement factors associated with mental health of refugees and internally displaced persons: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 294 (5): 602–12.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Betancourt, T. S., Newnham, E. A., Layne, C. M., Kim, S., Steinberg, A. M., Ellis, H. and Birman, D (2012). "Trauma history and psychopathology in war‐affected refugee children referred for trauma‐related mental health services in the United States". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 25 (6): 682–90.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Rousseau, C., Drapeau, A. and Corin, E (1996). "School performance and emotional problems in refugee children". American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 66 (2): 239–51.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hannides, T., Bailey, N. and Kaoukji, D (2016). "Voices of Refugees: Information and Communication Needs of Refugees in Greece and Germany". London, BBC Media Action.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gillespie, M., Ampofo, L., Cheesman, M., Faith, B., Iliadou, E., Issa, A., Osseiran, S. and Skleparis, D (2016). "Mapping Refugee Media Journeys: Smartphones and Social Media Networks". Milton Keynes, UK/ Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, Open University/France Médias Monde.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Manjoo, F (21 December 2016). "For millions of immigrants, a common language: WhatsApp". The New York Times.

- Kirk, J. and Winthrop, R (2007). "Promoting quality education in refugee contexts: supporting teacher development in Northern Ethiopia". International Review of Education. 53 (5/6): 715–23.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- UNHCR (2012). Education Strategy 2012–2016. Summary. Geneva, Switzerland. p. 12.

- UNHCR (2016). Missing Out: Refugee Education in Crisis. Geneva, Switzerland. p. 17.