Educational equity

Educational equity, also referred to as "Equity in education", is a measure of achievement, fairness, and opportunity in education. The study of education equity is often linked with the study of excellence and equity.

| Education |

|---|

| Disciplines |

| Curricular domains |

|

| Methods |

Educational equity depends on two main factors. The first is fairness, which implies that factors specific to one's personal conditions should not interfere with the potential of academic success. The second important factor is inclusion, which refers to a comprehensive standard that applies to everyone in a certain education system. These two factors are closely related and depend on each other for an educational system's success. Especially, equal rights for both genders.[1]

The growing importance of education equity is based on the premise that an individual’s level of education directly correlates to future quality of life.[1] Therefore, an academic system that practices educational equity is a strong foundation of a society that is fair and thriving. However, inequity in education is challenging to avoid, and can be broken down into inequity due to socioeconomic standing, race, gender or disability. Educational equity is also based in the historical context of the location, people and structure. History shapes the outcome of individuals within the education system[2].

Equity vs. equality

Often, the terms "equity" and "equality" are interchanged when referring to educational equity. Although similar, there can be important distinctions between the two.

Equity

Equity recognizes that some are at a larger disadvantage than others and aims at compensating for these peoples misfortunes and disabilities to ensure that everyone can attain the same type of healthy lifestyle. Examples of this are: “When libraries offer literacy programs, when schools offer courses in English as a second language, and when foundations target scholarships to students from poor families, they operationalize a belief in equity of access as fairness and as justice”.[3] Equity recognizes this uneven playing field and aims to take extra measures by giving those who are in need more than others who are not. Equity aims at making sure that everyone's lifestyle is equal even if it may come at the cost of unequal distribution of access and goods. Social justice leaders in education strive to ensure equitable outcomes for their students.

Equality

The American Library Association defines equality as: “access to channels of communication and sources of information that is made available on even terms to all--a level playing field--is derived from the concept of fairness as uniform distribution, where everyone is entitled to the same level of access and can avail themselves if they so choose.”[3] In this definition of equality no one person has an unfair advantage. Everyone is given equal opportunities and accessibility and are then free to do what they please with it. However, this is not to say that everyone is then inherently equal. Some people may choose to seize these open and equal opportunities while others let them pass by.

Educational Tracking

Tracking and Equity

Tracking systems, are selective measures to locate students in different educational levels[4]. They are created to increase the efficiency of education[5]. It allows to make more or less homogeneous groups of students to perceive education that suits their educational skills[6]. However, tracking can affect educational equity if the selection process is biased and children with a certain background are structurally located to lower tracks[7]. The effects of tracking are that students are both viewed and treated differently depending on which track they take. It can generate unequal achievement levels between individual students and it can restrict access to higher tracks and higher education[6]. The quality of teaching and curricula vary between tracks and as a result, those of the lower track are disadvantaged with inferior resources, teachers, etc. In many cases, tracking stunts students who may develop the ability to excel past their original placement.

Tracking systems

The type of tracking has impact on the level of educational equity, which is especially determined by the degree in which the system is differentiated. Less differentiated systems, such as standardized comprehensive schools, reach higher levels of equity in comparison to more differentiated, or tracked, systems[8].

Within the tracked systems, the kind of differentiation matters as well for educational equity. Differentiation of schools could be organized externally or internally[4]. External differentiation means that tracks are separated in different schools. Certain schools follow a certain track, which prepares students for academic or professional education, or for career or vocational education. This form is less beneficial for educational equity than internal differentiation or course-by-course tracking[9]. Internal tracking means that, within a single school, courses are instructed at different levels, which is a less rigid kind of tracking that allows for more mobility[9].

The organization of the tracking systems themselves is also important for its effect on educational equity. For both differentiation systems, a higher amount of tracks and a smaller amount of students per track is granting more educational equity[6]. In addition, the effects of tracking are less rigid and have a smaller impact on equity if the students are located in tracks when they are older[9]. The earlier the students undergo educational selection, the less mobile they are to develop their abilities and the less they can benefit from peer effects[5].

Socio-economic equity in education

Income and class

Income has always played an important role in shaping academic success. Those who come from a family of a higher socioeconomic status (SES) are privileged with more opportunities than those of lower SES. Those who come from a higher SES can afford things like better tutors, rigorous SAT/ACT prep classes, impressive summer programs, and so on. Parents generally feel more comfortable intervening on behalf of their children to acquire better grades or more qualified teachers (Levitsky). Parents of a higher SES are more willing to donate large sums of money to a certain institution to better improve their child's chances of acceptance, along with other extravagant measures. This creates an unfair advantage and distinct class barrier.

Costs of education

The extraordinarily high cost of the many prestigious high schools and universities in the United States makes an attempt at a "level playing field" for all students not so level. High-achieving low-income students do not have the means to attend selective schools that better prepare a student for later success. Because of this, low-income students do not even attempt to apply to the top-tier schools for which they are more than qualified. In addition, neighborhoods generally segregated by class leave lower-income students in lower-quality schools. For higher-quality schooling, students in low-income areas would have to take public transport which they can't pay for. Fewer than 30 percent of students in the bottom quarter of incomes even enroll in a four-year school and among that group, fewer than half graduate.[10]

Racial equity in education

From a scientific point of view, the human species is a single species. Nevertheless, the term racial group is enshrined in legislation, and phrases such as race equality and race relations are in widespread official use.[11] Racial equity in education means the assignment of students to public schools and within schools without regard to their race. This includes providing students with a full opportunity for participation in all educational programs regardless of their race.[12]

The educational system and its response to racial concerns in education vary from country to country. Below are some examples of countries that have to deal with racial discrimination in education.

- US Department of Education: The Commission on Equity and Excellence in Education issues a seminal report in 2013. It is not a restatement of public education's struggles, nor is it a mere list of recommendations. Rather, this is a declaration of an urgent national mission: to provide equity and excellence in education in American public schools once and for all. This collective wisdom is a historic blueprint for making the dream of equity, and a world-class education, for each and every American child a reality.[13]

The struggle for equality of access to formal education and equality of excellent educational outcomes is part of the history of education in this country and is tied up with the economic, political, social history of the peoples who are part of it. From the beginning of this nation, there were many barriers to the schooling and education of girls and racial, national origin, and language groups not from the dominant culture. Approaches and resources for achieving equality and equity in the public schooling of girls and ethnic, racial, and language minority groups are still evolving.[14]

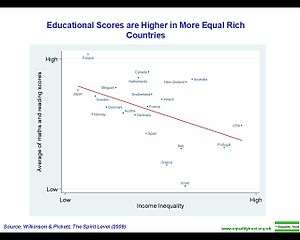

- Asia-Pacific Region: Globalization of the economy, increasingly diverse and interconnected populations, and rapid technological change are posing new and demanding challenges to individuals and societies alike. School systems are rethinking the knowledge and skills students need for success, and the educational strategies and systems required for all children to achieve them. Within the Asia-Pacific region, for example, Korea, Shanghai-China, and Japan are examples of Asian education systems that have climbed the ladder to the top in both quality and equity indicators.[15]

- South Africa: A major task of South Africa's new government in 1994 was to promote racial equity in the state education system. During the apartheid era, which began when the National Party won control of Parliament in 1948 and ended with a negotiated settlement more than four decades later, the provision of education was racially unequal by design. Resources were lavished on schools serving white students while schools serving the black majority were systematically deprived of qualified teachers, physical resources and teaching aids such as textbook and stationery. The rationale for such inequity was a matter of public record.[16]

Students wanting to be more involved in the community. [17]Not feeling left out, which I think is a good feeling being that race was a big problem. They gave them transportation to get to the meetings and back to where they were going after.

Higher education

Higher education plays a vital role in preparing students for the employment market and active citizenship both nationally and internationally. By embedding race equality in teaching and learning, institutions can ensure that they acknowledge the experiences and values of all students, including minority ethnic and international students. Universities Scotland first published the Race Equality Toolkit: learning and teaching in 2006 in response to strong demand from the universities in Scotland for guidance on meeting their statutory obligations.[18]

Gender equity in education

Gender equity in practicality refers to both male and female concerns, yet most of the gender bias is against women in the developing world. Gender discrimination in education has been very evident and underlying problem in many countries, especially in developing countries where cultural and societal stigma continue to hinder growth and prosperity for women. Global Campaign for Education (GCE) followed a survey called "Gender Discrimination in Violation of Rights of Women and Girls" states that one tenth of girls in primary school are 'unhappy' and this number increases to one fifth by the time they reach secondary schools. Some of the reasonings that girls provided include harassment, restorations to freedom, and an inherent lack of opportunities, compared to boys.[19] United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) understands Education as a " fundamental human right and essential for the exercise of all other human rights. It promotes individual freedom and empowerment and yields important development benefits."[20]

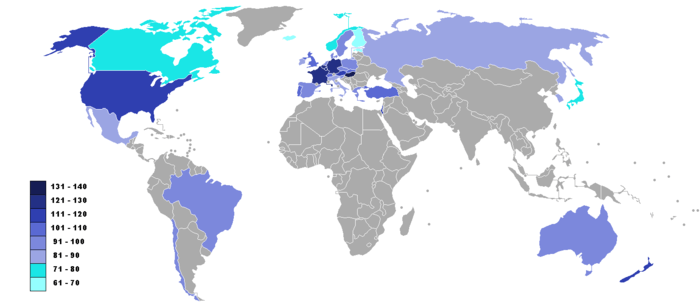

UN Special Rapporteur Katarina Tomasevki developed the '4A' framework on the Right to Education. The '4A' framework encompasses availability, accessibility, acceptability and adaptability as fundamental to the institution of education. And yet girls in many underdeveloped countries are denied secondary education. Figure on the right shows the discrepancies in secondary education in the world. Countries such as Sudan, Somalia, Thailand and Afghanistan face the highest of inequity when it comes to gender bias.[21]

Gender-based inequity in education is not just a phenomenon in developing countries. A New York Times article[22] highlighted how education systems, especially the public school system, tend to cause segregation between genders. Boys and girls are often taught with different approaches, which programs children to think they are different and deserve different treatment. However, studies show that boys and girls learn differently, and therefore should be taught differently. Boys learn better when they keep moving, while girls learn better sitting in one place with silence. Therefore—in this reasoning—segregating the genders promotes gender equity in education, as both boys and girls have optimized learning.[23]

Causes of gender discrimination in education

VSO is a leading independent international development organization that works towards eliminating poverty and one of the problems they tackle is gender inequity in education.[24] VSO published a paper that categorizes the obstacles (or causes) into:

- Community Level Obstacles: This category primarily relates to the bias displayed for education external to the school environment. This includes restraints due to poverty and child labour, socio-economic constraints, lack of parental involvement and community participation. Harmful practices like child marriage and predetermined gender roles are cultural hindrances.[25]

- School and Education System Level Obstacles: Lack of investment in quality education, inappropriate attitudes and behaviors, lack of female teachers as role models and lack of gender-friendly school environment are all factors that promote gender inequity in education.[26]

Impact of gender discrimination on the economy

Education is universally acknowledged as an essential human right because it highly impacts the socio-economic and cultural aspects of a country. Equity in education increases the work force of the nation, therefore increasing national income, economic productivity, and [gross domestic product]. It reduces fertility and infant mortality, improves child health, increases life expectancy and increases standards of living.[27] These are factors that allow economic stability and growth in the future. Above all, female education can increase output levels and allow countries to attain sustainable development. Equity in education of women also reduces the possibilities of trafficking and exploitation of women. UNESCO also refers gender equity as a major factor that allows for sustainable development.[28] https://www.economist.com/blogs/freeexchange/2013/11/gender-inequality[29] is an article published by The Economist, which says:

"Looking at recently-published UN statistics on gender inequality in education, one observes that the overall picture has improved dramatically over the last decade, but progress has not been even (see chart). Although the developing world on average looks likely to hit the UN’s gender-inequality target, many parts of Africa are lagging behind. While progress is being made in sub-Saharan Africa in primary education, gender inequality is in fact widening among older children. The ratio of girls enrolled in primary school rose from 85 to 93 per 100 boys between 1999 and 2010, whereas it fell from 83 to 82 and from 67 to 63 at the secondary and tertiary levels."

Reputable research centers and associations

- University of Pennsylvania: The Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education unites University of Pennsylvania scholars who do research on race, racism, racial climates, and important topics pertaining to equity in education. Center staff and affiliates collaborate on funded research projects, environmental assessment activities, and the production of research reports. Principally, the Center aims to publish cutting-edge implications for education policy and practice, with an explicit focus on improving equity in schools, colleges and universities, and social contexts that influence educational outcomes.[30]

- Programs for Educational Opportunity, University of Michigan: 'Equity in Elementary and Secondary Education: Race, Gender, and National Origin Issues' is a site composed of article reviews and final papers from students enrolled in an courses at the University of Michigan School of Education focusing on equity and social justice issues in education starting the Fall of 2007. What follows is a work in progress, started by members of a class entitled "Equity in K–12 Public Education" held the Fall of 2007 and "Equity and Social Justice in Education: Race, Gender, National Origin, and Language Minority Issues in Schools" the Fall of 2008 at the University of Michigan School of Education. The site has timelines, reviews of articles on selected issues, and additional resources.[14]

- Equity and Quality in Education (Asia Society): Asia Society is the leading educational organization dedicated to promoting mutual understanding and strengthening partnerships among peoples, leaders and institutions of Asia and the United States in a global context. Across the fields of arts, business, culture, education, and policy, the Society provides insight, generates ideas, and promotes collaboration to address present challenges and create a shared future. The highest performing education systems are those that combine quality with equity. Equity in education means that personal or social circumstances such as gender, ethnic origin or family background, are not obstacles to achieving educational potential (definition of fairness) and that all individuals reach at least a basic minimum level of skills (definition of inclusion). In these education systems, the vast majority of students have the opportunity to attain high-level skills, regardless of their own personal and socio-economic circumstances.[15]

- Regional Educational Laboratory Northwest: REL Northwest is part of the Regional Educational Laboratory (REL) Program funded by the U.S. Department of Education's Institute of Education Sciences. Education Northwest works to transform teaching and learning by providing resources that help schools, districts, and communities across the country find comprehensive, research-based solutions to the challenges they face.[12]

- IDRA South Central Collaborative for Equity: The Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) is an independent, non-profit organization that is dedicated to assuring educational opportunity for every child. The South Central Collaborative for Equity helps schools become more racially equitable, ensure equal opportunity for academic achievement, provide fair discipline, decrease conflict, and engage parents and community members.[31]

- PPS Racial Educational Equity Policy: The Board of Education for Portland Public Schools (PPS) is committed to the success of every student in each of our schools. The mission of Portland Public Schools is that by the end of elementary, middle, and high school, every student by name will meet or exceed academic standards and be fully prepared to make productive life decisions. We believe that every student has the potential to achieve, and it is the responsibility of our school district to give each student the opportunity and support to meet his or her highest potential.[32]

- National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education (NCSEHE): Funded by the Department of Education (Australia) and currently based at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia, the NCSEHE promotes discussion and research of Australian higher education equity policy. The Centre undertakes and informs policy design, implementation, and institutional practice to improve higher education participation and success for marginalised and disadvantaged people in Australia.[33]

- Seed the Way: Founded by Rebecca Eun-Mi Haslam, 2015 Vermont teacher of the year. Haslam believes in equity and her company Seed the Way focuses on establishing equity in the classroom.

Notable publications and reports

Providing opportunities for students to consider racial equality as well as matters of racism as part of their study will help them to develop confidence to engage with these concepts as part of future practice, thinking, and life skills. Race, social class, and gender as issues related to schooling have received major attention from educators and social scientists over the last two decades.

Race equality in education - a survey report by England

The local authorities in England gave a survey report Race equality in education in November 2005.[34] This report is based on visits by Her Majesty.s Inspectors (HMIs) and additional inspectors to 12 LEAs and 50 schools in England between summer term 2003 to spring term 2005. This report illustrates good practice on race equality in education in a sample of schools and local education authorities (LEAs) surveyed between the summer of 2003 and the spring of 2005. The survey focused on schools and LEAs that were involved effectively in race equality in education. Four areas were examined by inspectors: improving standards and achievement amongst groups of pupils, with reference to the Race Relations (Amendment) Act 2000 (RRAA); the incorporation of race equality concepts into the curriculum in schools; the handling and reporting of race-related incidents in schools; the work of schools and LEAs in improving links with local minority ethnic communities.

Race equality and education – by UK educational system

The Association of Teachers and Lecturers (ATL) (ATL promotes and protects the interests of its members – teachers, lecturers, support staff and other education professionals) introduced a practical resource for the school workforce Race equality and education in the UK educational system. The publication sets out to examine the racial, religious or cultural terminology regularly used in today's society, in an attempt to combat prejudice based on colour, ethnicity, religion or culture.[11]

The equity and excellence commission - US education

At this decisive moment, the Commission on Equity and Excellence in Education issues this seminal report. It is not a restatement of public education's struggles, nor is it a mere list of recommendations. Rather, this is a declaration of an urgent national mission: to provide equity and excellence in education in American public schools once and for all. This collective wisdom is a historic blueprint for making the dream of equity, and a world-class education, for each and every American child a reality.[13] Carol D. Lee described the rationale for a special theme issue, "Reconceptualizing Race and Ethnicity in Educational Research." The rationale includes the historical and contemporary ways that cultural differences have been positioned in educational research and the need for more nuanced and complex analyses of ethnicity and race.[35]

Racial equity in education: how far has South Africa come?

A major task of South Africa’s new government in 1994 was to promote racial equity in the state education system. This paper evaluates progress towards this goal using three distinct concepts: equal treatment, equal educational opportunity, and educational adequacy. The authors find that the country has succeeded in establishing racial equity defined as equal treatment, primarily through race-blind policies for allocating state funds for schools. Progress measured by the other two criteria, however, has been constrained by the legacy of apartheid, including poor facilities and lack of human capacity in schools serving black students, and by policies such as school fees.[16]

Race in education: an argument for integrative analysis

Education literature tends to treat race, social class, and gender as separate issues. A review of a sample of education literature from four academic journals, spanning ten years, sought to determine how much these status groups were integrated. The study found little integration. The study then provided a research example on cooperative learning to illustrate how attention to only one status group oversimplifies the analysis of student behavior in school. From findings of studies integrating race and class, and race and gender, the study argues that attending only to race, in this example, oversimplifies behavior analysis and may help perpetuate gender and class biases. To determine to what extent race, social class, and gender are integrated in the education literature, the study examined a sample of literature published over a ten-year period and 30 articles focused primarily on race, or on school issues related directly to race, such as desegregation.[36]

Equity and quality in education: supporting disadvantaged students and schools–from OECD

The report is by the OECD Education Directorate with support from the Asia Society as a background report for the first Asia Society Global Cities Network Symposium, Hong Kong, May 10–12, 2012. Asia Society is grateful for OECD's leadership in international benchmarking and for our ongoing partnership. Asia Society organized the Global Cities Education Network, a network of urban school systems in North America and Asia to focus on challenges and opportunities for improvement common to them, and to virtually all city education systems. This report presents the key recommendations of the OECD publication Equity and Quality in Education: Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools (2012a), which maps out policy levers that can help build high quality and equitable education systems, with a particular focus on North American and Asia-Pacific countries.[37]

Challenges in educational equity

The long-term social and economic consequences of having little education are more tangible now than ever before. Those without the skills to participate socially and economically in society generate higher costs of healthcare, income support, child welfare and social security.[1]

Societal structure and costs

While both basic education and higher education have both been improved and expanded in the past 50 years, this has not translated to a more equal society in terms of academics. While the feminist movement has made great strides for women, other groups have not been as fortunate. Generally, social mobility has not increased, while economic inequality has.[1] So, while more students are getting a basic education and even attending universities, a dramatic divide is present and many people are still being left behind.

Increase migration and diversity

As increased immigration causes problems in educational equity for some countries, poor social cohesion in other countries is also a major issue. In countries where continued migration causes an issue, the ever-changing social structure of different races makes it difficult to propose a long-term solution to educational equity. On the other hand, many countries with consistent levels of diversity experience long-standing issues of integrating minorities. Challenges for minorities and migrants are often exacerbated as these groups statistically struggle more in terms of both lower academic performance and lower socio-economic status.[1]

See also

- Brown v. Board of Education - United States Supreme Court case that determined segregating public schools unconstitutional

- Female education

- Gender inequality in curricula

- Right to education

- Sex differences in education

References

- "Ten Steps to Equity in Education" (PDF). Oecd.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Kozol, Jonathan (1991). Savage Inequalities. Broadway Books. ISBN 0770435688.

- "Equality and Equity of Access: What's the Difference?". Ala.org. May 29, 2007. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Triventi, Moris; Kulic, Nevena; Skopek, Jan; Blossfeld, Hans Peter (2016). Models of Secondary Education and Social Inequality: An International Comparison. eduLIFE Lifelong Learning series. pp. 3–24.

- Hanushek, Eric; Wößmann, Ludger (2006). "Does Educational Tracking Affect Performance and Inequality? Differences-in‐Differences Evidence Across Countries". The Economic Journal. 116 (510): 63–76. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2006.01076.x.

- Hallinan, Maureen (1991). "School Differences in Tracking Structures and Track Assignments". Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1 (3): 251–275. doi:10.1207/s15327795jra0103_4.

- Lynch, Kathleen; Baker, John (2005). "Equality in education: An equality of condition perspective". Theory and Research in Education. 3 (2): 131–164. doi:10.1177/1477878505053298.

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman; Mijs, Jonathan (2010). "Achievement inequality and the institutional structure of educational systems: A comparative perspective". Annual Review of Sociology. 36: 407–428. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102538.

- Chmielewski, Anna (2014). "An International Comparison of Achievement Inequality in Within- and Between-School Tracking Systems". American Journal of Education. 120 (3): 293–324. doi:10.1086/675529.

- "Poor Students Struggle as Class Plays a Greater Role in Success". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Race equality and education : A practical resource for the school workforce : A resource written by Robin Richardson for the Association of Teachers and Lecturers" (PDF). Atl.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Region X Equity Assistance Center - Education Northwest". Educationnorthwest.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "The Equity and Excellence Commission For Each and Every Child" (PDF). Atl.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Equity In Elementary and Secondary Education: Race, Gender, and National Origin Issues: Home". Sitemaker.umich.edu. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Equity and Quality in Education". Asia Society. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Racial Equality in Education : How Far Has South Africa Come?" (PDF). Atl.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Chapter Thirty-Two: John Ogbu, Black American Students in an Affluent Suburb: A Study of Academic Disengagement (2003)", Popular Educational Classics, Peter Lang, 2016, doi:10.3726/978-1-4539-1735-0/47, ISBN 978-1-4331-2834-9

- "Race Equality Toolkit". Universities-scotland.ac.uk. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Anne. "Gender Discrimination in Education". Acei.org. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "The Right to Education - Education - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". Unesco.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Discrepancy in Secondary Education" (PDF). Atl.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Teaching boys and girls separately". The New York Times. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Gender Differences: The Impact of Gender Stereotyping on School Environment - The Art of Manliness". The Art of Manliness. March 5, 2008. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Archived February 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "Gender Equality - Education - United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization". Unesco.org. May 10, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Gender Equality and Education" (PDF). Vsointernational.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 20, 2013. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Gender Effects of Education on Economic Development in Turkey" (PDF). Ftp.iza.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "EDUCATION FROM A GENDER EQUALITY PERSPECTIVE" (PDF). Ungei.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Gender inequality". The Economist. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Mission and Purpose | Center for the Study of Race & Equity in Education

- "IDRA - Educational Equity and Race". Idra.org. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Racial Educational Equity Policy - Portland Public Schools". Pps.k12.or.us. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "About - National Centre for Student Equity in Higher Education". NCSEHE. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Ofsted - Race equality in education". Ofsted.gov.uk. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Lee, Carol D. (2003). "Why We Need to Re-Think Race and Ethnicity in Educational Research". Educational Researcher. Edr.sagepub.com. 32 (5): 3–5. doi:10.3102/0013189X032005003. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- Grant, Carl A.; Sleeter, Christine E. (June 1986). "Sign In". Review of Educational Research. Rer.sagepub.com. 56 (2): 195–211. doi:10.3102/00346543056002195. Retrieved November 19, 2014.

- "Equity and Quality in Education : Supporting Disadvantaged Students and Schools" (PDF). Asiasociety.org. Retrieved November 19, 2014.