Maastricht

Maastricht (/ˈmɑːstrɪxt, -ɪkt/, also US: /mɑːˈs-/,[8][9][10] Dutch: [maːˈstrɪxt] (![]()

Maastricht Mestreech (Limburgish) | |

|---|---|

City and municipality | |

From top to bottom, left to right: river Meuse in winter · Town Hall by night · sidewalk cafés at Onze Lieve Vrouweplein · Saint Servatius Bridge · Our Lady, Star of the Sea chapel · St. John's and St. Servatius' churches at Vrijthof square · View from Mount Saint Peter | |

| Anthem: Mestreechs Volksleed | |

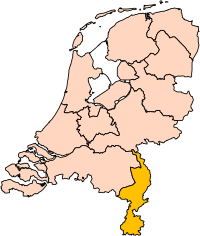

.svg.png) Location in Limburg | |

| Coordinates: 50°51′N 5°41′E | |

| Country | Netherlands |

| Province | |

| Settled | ≈ 50 BC |

| City rights | 1204 |

| City Hall | Maastricht City Hall |

| Boroughs | 5 districts

|

| Government | |

| • Body | Municipal council |

| • Mayor | Annemarie Penn-te Strake (independent) |

| Area | |

| • Municipality | 60.03 km2 (23.18 sq mi) |

| • Land | 56.81 km2 (21.93 sq mi) |

| • Water | 3.22 km2 (1.24 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 49 m (161 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Municipality | 121,565 |

| • Density | 2,140/km2 (5,500/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 277,721 |

| • Metro | ≈ 3,500,000 |

| Urban population for Dutch-Belgian region;[6] metropolitan population for Dutch-Belgian-German region.[7] | |

| Demonyms | (Dutch) Maastrichtenaar; (Limb.) Mestreechteneer or "Sjeng" (nickname) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postcode | 6200–6229 |

| Area code | 043 |

| Website | www |

Maastricht developed from a Roman settlement (Trajectum ad Mosam) to a medieval religious centre. In the 16th century it became a garrison town and in the 19th century an early industrial city.[12] Today, the city is a thriving cultural and regional hub. It became well known through the Maastricht Treaty and as the birthplace of the euro.[13] Maastricht has 1677 national heritage buildings (Rijksmonumenten), the second highest number in the Netherlands, after Amsterdam. The city is visited by tourists for shopping and recreation, and has a large international student population. Maastricht is a member of the Most Ancient European Towns Network[14] and is part of the Meuse-Rhine Euroregion, which includes the nearby German and Belgian cities of Aachen, Eupen, Hasselt, Liège, and Tongeren. The Meuse-Rhine Euroregion is a metropolis with a population of about 3.9 million with several international universities.

History

Toponymy

Maastricht is mentioned in ancient documents as [Ad] Treiectinsem [urbem] ab. 575, Treiectensis in 634, Triecto, Triectu in 7th century, Triiect in 768–781, Traiecto in 945, Masetrieth in 1051.[15][16]

The place name Maastricht is an Old Dutch compound Masa- (> Maas "the Meuse river") + Old Dutch *treiekt, itself borrowed from Gallo-Romance *TRA(I)ECTU cf. its Walloon name li trek, from Classical Latin trajectus ("ford , passage, place to cross a river") with the later addition of Maas "Meuse" to avoid the confusion with the -trecht of Utrecht having exactly the same original form and etymology. The Latin name first appears in medieval documents and it is not known whether *Trajectu(s) was Maastricht's name during Roman times. A resident of Maastricht is referred to as Maastrichtenaar whilst in the local dialect it is either Mestreechteneer or, colloquially, Sjeng (derived from the formerly popular French name Jean).

Early history

Neanderthal remains have been found to the west of Maastricht (Belvédère excavations). Of a later date are Palaeolithic remains, between 8,000 and 25,000 years old. Celts lived here around 500 BC, at a spot where the river Meuse was shallow and therefore easy to cross.

It is not known when the Romans arrived in Maastricht, or whether the settlement was founded by them. The Romans built a bridge across the Meuse in the 1st century AD, during the reign of Augustus Caesar. The bridge was an important link in the main road between Bavay and Cologne. Roman Maastricht was probably relatively small. Remains of the Roman road, the bridge, a religious shrine, a Roman bath, a granary, some houses and the 4th-century castrum walls and gates, have been excavated. Fragments of provincial Roman sculptures, as well as coins, jewellery, glass, pottery and other objects from Roman Maastricht are on display in the exhibition space of the city's public library (Centre Céramique).

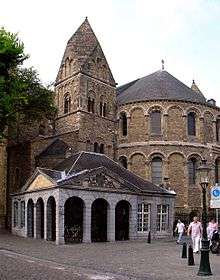

According to legend, the Armenian-born Saint Servatius, Bishop of Tongeren, died in Maastricht in 384 where he was interred along the Roman road, outside the castrum. According to Gregory of Tours bishop Monulph was to have built around 570 the first stone church on the grave of Servatius, the present-day Basilica of Saint Servatius. The city remained an early Christian diocese until it lost the distinction to nearby Liège in the 8th or 9th century.

Middle Ages

In the early Middle Ages Maastricht was part of the heartland of the Carolingian Empire along with Aachen and the area around Liège. The town was an important centre for trade and manufacturing. Merovingian coins minted in Maastricht have been found in places throughout Europe. In 881 the town was plundered by the Vikings. In the 10th century it briefly became the capital of the duchy of Lower Lorraine.

During the 12th century the town flourished culturally. The provosts of the church of Saint Servatius held important positions in the Holy Roman Empire during this era. The two collegiate churches were largely rebuilt and redecorated. Maastricht Romanesque stone sculpture and silversmithing are regarded as highlights of Mosan art. Maastricht painters were praised by Wolfram von Eschenbach in his Parzival. Around the same time, the poet Henric van Veldeke wrote a legend of Saint Servatius, one of the earliest works in Dutch literature. The two main churches acquired a wealth of relics and the septennial Maastricht Pilgrimage became a major event.

Unlike most Dutch towns, Maastricht did not receive city rights at a certain date. These developed gradually during its long history. In 1204 the city's dual authority was formalised in a treaty, with the prince-bishops of Liège and the dukes of Brabant holding joint sovereignty over the city. Soon afterwards the first ring of medieval walls were built. In 1275, the old Roman bridge collapsed under the weight of a procession, killing 400 people. A replacement, funded by church indulgences, was built slightly to the north and survives until today, the Sint Servaasbrug.[17]

Throughout the Middle Ages, the city remained a centre for trade and manufacturing principally of wool and leather but gradually economic decline set in. After a brief period of economic prosperity around 1500, the city's economy suffered during the wars of religion of the 16th and 17th centuries, and recovery did not happen until the industrial revolution in the early 19th century.

16th to 18th centuries

The important strategic location of Maastricht resulted in the construction of an impressive array of fortifications around the city during this period. The Spanish and Dutch garrisons became an important factor in the city's economy. In 1579 the city was sacked by the Spanish army led by the Duke of Parma (Siege of Maastricht, 1579). For over fifty years the Spanish crown took over the role previously held by the dukes of Brabant in the joint sovereignty over Maastricht. In 1632 the city was conquered by Prince Frederick Henry of Orange and the Dutch States General replaced the Spanish crown in the joint government of Maastricht.

Another Siege of Maastricht (1673) took place during the Franco-Dutch War. In June 1673, Louis XIV laid siege to the city because French supply lines were being threatened. During this siege, Vauban, the famous French military engineer, developed a new tactic in order to break down the strong fortifications surrounding Maastricht. His systematic approach remained the standard method of attacking fortresses until the 20th century. On 25 June 1673, while preparing to storm the city, captain-lieutenant Charles de Batz de Castelmore, also known as the comte d'Artagnan, was killed by a musket shot outside the Tongerse Poort. This event was embellished in Alexandre Dumas' novel The Vicomte de Bragelonne, part of the D'Artagnan Romances. French troops occupied Maastricht from 1673 to 1678.

In 1748 the French again conquered the city at what is known as the Second French Siege of Maastricht, during the War of Austrian Succession. The French took the city for the last time in 1794, when the condominium was dissolved and Maastricht was annexed to the First French Empire (1794–1814). For twenty years Maastricht remained the capital of the French département of Meuse-Inférieure.

19th and early 20th century

After the Napoleonic era, Maastricht became part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands in 1815. It was made the capital of the newly formed Province of Limburg (1815–1839). When the southern provinces of the newly formed kingdom seceded in 1830, the Dutch garrison in Maastricht remained loyal to the Dutch king, William I, even when most of the inhabitants of the town and the surrounding area sided with the Belgian revolutionaries. In 1831, arbitration by the Great Powers allocated the city to the Netherlands. However, neither the Dutch nor the Belgians agreed to this and the arrangement was not implemented until the 1839 Treaty of London. During this period of isolation Maastricht developed into an early industrial town.

Because of its eccentric location in the southeastern Netherlands, and its geographical and cultural proximity to Belgium and Germany, integration of Maastricht and Limburg into the Netherlands did not come about easily. Maastricht retained a distinctly non-Dutch appearance during much of the 19th century and it was not until the First World War that the city was forced to look northwards.

Like the rest of the Netherlands, Maastricht remained neutral during World War I. However, being wedged between Germany and Belgium, it received large numbers of refugees, putting a strain on the city's resources. Early in World War II, the city was taken by the Germans by surprise during the Battle of Maastricht of May 1940. On 13 and 14 September 1944 it was the first Dutch city to be liberated by Allied forces of the US Old Hickory Division. The three Meuse bridges were destroyed or severely damaged during the war. As elsewhere in the Netherlands, the majority of Maastricht Jews died in Nazi concentration camps.[18]

After World War II

During the latter half of the century, traditional industries (such as Maastricht's potteries) declined and the city's economy shifted to a service economy. Maastricht University was founded in 1976. Several European institutions found their base in Maastricht. In 1981 and 1991 European Councils were held in Maastricht, the latter one resulting a year later in the signing of the Maastricht Treaty, leading to the creation of the European Union and the euro.[19] Since 1988, The European Fine Art Fair, regarded as the world's leading art fair, annually draws in some of the wealthiest art collectors.

In recent years, Maastricht launched several campaigns against drug-dealing in an attempt to stop foreign buyers taking advantage of the liberal Dutch legislation and causing trouble in the downtown area.[20]

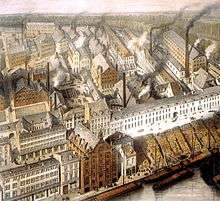

Since the 1990s, large parts of the city have been refurbished, including the areas around the main railway station and the Maasboulevard promenade along the Meuse, the Entre Deux and Mosae Forum shopping centres, as well as some of the main shopping streets. A prestigious quarter designed by international architects and including the new Bonnefanten Museum, a public library, and a theatre was built on the grounds of the former Société Céramique factory near the town centre. Further large-scale projects, such as the redevelopment of the area around the A2 motorway, the Sphinx Quarter and the Belvédère area are under construction.

Geography

Neighbourhoods

Maastricht consists of five districts (stadsdelen) and 44 neighbourhoods (wijken). Each neighbourhood has a number which corresponds to its postal code.

- Maastricht Centrum (Binnenstad, Jekerkwartier, Kommelkwartier, Statenkwartier, Boschstraatkwartier, Sint Maartenspoort, Wyck-Céramique)

- South-West (Villapark, Jekerdal, Biesland, Campagne, Wolder, Sint Pieter)

- North-West (Brusselsepoort, Mariaberg, Belfort, Pottenberg, Malpertuis, Caberg, Malberg, Dousberg-Hazendans, Daalhof, Boschpoort, Bosscherveld, Frontenkwartier, Belvédère, Lanakerveld)

- North-East (Beatrixhaven, Borgharen, Itteren, Meerssenhoven, Wyckerpoort, Wittevrouwenveld, Nazareth, Limmel, Amby)

- South-East (Randwyck, Heugem, Heugemerveld, Scharn, Heer, De Heeg, Vroendaal)

The neighbourhoods of Itteren, Borgharen, Limmel, Amby, Heer, Heugem, Scharn, Oud-Caberg, Sint Pieter and Wolder all used to be separate municipalities or villages until they were annexed by the city of Maastricht in the course of the 20th century.

Neighbouring municipalities

The outlying areas of the following municipalities are bordering the municipality of Maastricht directly.

Clockwise from north-east to north-west:

- Bunde,

- Meerssen,

- Berg en Terblijt,

- Bemelen,

- Cadier en Keer,

- Gronsveld,

- Oost,

- Lanaye (B),

- Petit-Lanaye (B),

- Kanne (B),

- Vroenhoven (B),

- Kesselt (B),

- Veldwezelt (B),

- Lanaken (B),

- Neerharen (B).

(B = Situated in Belgium)

Border

Maastricht's city limits has an international border with Belgium. Most of it borders Belgium's Flemish region, but a small part to the south also has a border with the Walloon region. Both countries are part of Europe's Schengen Area thus are open without border controls.

Climate

Maastricht features the same climate as most of the Netherlands (Cfb, Oceanic climate), however, due to its more inland location in between hills, summers tend to be warmer (especially in the Meuse valley, which lies 70 metres lower than the meteorological station) and winters a bit colder, although the difference is only noticeable on just a few days a year. The highest temperature recorded was on 25 July 2019 at 39.6 °C (103.3 °F).[21]

| Climate data for Maastricht | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.1 (62.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

23.4 (74.1) |

29.7 (85.5) |

33.1 (91.6) |

37.2 (99.0) |

39.6 (103.3) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

28.7 (83.7) |

21.4 (70.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

6.1 (43.0) |

10.1 (50.2) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.3 (64.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

9.2 (48.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.7 (36.9) |

3.1 (37.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

16.2 (61.2) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

14.7 (58.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 0.0 (32.0) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.5 (56.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

3.5 (38.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

6.3 (43.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −19.3 (−2.7) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

−12.9 (8.8) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

0.7 (33.3) |

4.3 (39.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−12.0 (10.4) |

−18.3 (−0.9) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 65.3 (2.57) |

57.4 (2.26) |

61.8 (2.43) |

45.1 (1.78) |

65.9 (2.59) |

70.5 (2.78) |

69.6 (2.74) |

72.3 (2.85) |

61.6 (2.43) |

67.2 (2.65) |

65.3 (2.57) |

70.8 (2.79) |

772.7 (30.42) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 12 | 10 | 12 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 12 | 12 | 126 |

| Average snowy days | 7 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 6 | 31 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 87 | 84 | 80 | 74 | 73 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 82 | 85 | 89 | 89 | 81 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 59.9 | 79.3 | 119.3 | 164.0 | 194.9 | 188.9 | 202.8 | 187.3 | 140.0 | 113.6 | 65.9 | 44.9 | 1,560.8 |

| Source 1: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (1981–2010 normals, snowy days normals for 1971–2000)[22] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (1971–2000 extremes)[23] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

Historical population

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1400 | 7,000 | — |

| 1500 | 10,000 | +0.36% |

| 1560 | 13,500 | +0.50% |

| 1600 | 12,600 | −0.17% |

| 1650 | 18,000 | +0.72% |

| 1740 | 12,500 | −0.40% |

| 1796 | 17,963 | +0.65% |

| 1818 | 20,000 | +0.49% |

| 1970 | 93,927 | +1.02% |

| 1980 | 109,285 | +1.53% |

| 1990 | 117,008 | +0.69% |

| 2000 | 122,070 | +0.42% |

| 2010 | 118,533 | −0.29% |

| Source: Lourens & Lucassen 1997, pp. 32–33 (1400-1795) Statistics Netherlands (1970-2010) | ||

Inhabitants by nationality

| Maastricht residents by nationality - Top 10 (1 January 2014)[24] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | 2014 | 2010 | 2000 |

| 107,418 | 109,722 | 116,171 | |

| 3,869 | 1,956 | 783 | |

| 1,055 | 946 | 909 | |

| 815 | 386 | 280 | |

| 653 | 387 | 280 | |

| 623 | 277 | 162 | |

| 595 | 248 | 87 | |

| 431 | 232 | 241 | |

| 404 | 368 | 404 | |

| 351 | 214 | 120 | |

Inhabitants by country of birth

| Maastricht residents by country of birth - Top 10 (1 January 2013)[25] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | 2013 | 2010 | 2000 |

| 100,269 | 102,433 | 109,632 | |

| 4,100 | 2,467 | 1,444 | |

| 1,920 | 1,839 | 1,900 | |

| 1,199 | 1,267 | 1,556 | |

| 919 | 836 | 784 | |

| 838 | 867 | 859 | |

| Former Soviet Union | 842 | 564 | 183 |

| 753 | 383 | 217 | |

| 677 | 404 | 310 | |

| 651 | 373 | 215 | |

Languages

Maastricht is a city of linguistic diversity, partly as a result of its location at the crossroads of multiple language areas and its international student population.

Religions in Maastricht (2013)[26]

- Dutch is the national language and the language of elementary and secondary education (excluding international institutions) as well as administration. Dutch in Maastricht is often spoken with a distinctive Limburgish accent, which should not be confused with the Limburgish language.

- Limburgish (or Limburgian) is the overlapping term of the tonal dialects spoken in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg. The Maastrichtian dialect (Mestreechs) is only one of many variants of Limburgish. It is characterised by stretched vowels and some French influence on its vocabulary. In recent years the Maastricht dialect has been in decline (see dialect levelling) and a language switch to Standard Dutch has been noted.[27]

- French used to be the language of education in Maastricht. In the 18th century the language occupied a powerful position as judicial and cultural language, and it was used throughout the following century by the upper classes.[28] Between 1851 and 1892 a Francophone newspaper (Le Courrier de la Meuse) was published in Maastricht. The language is often part of secondary school curricula. Many proper names and some street names are French and the language has left many traces in the local dialect.

- German, like French, is often part of secondary school curricula. Due to Maastricht's geographic proximity to Germany and the great number of German students in the city, German is widely spoken.

- English has become an important language in education. At Maastricht University and Hogeschool Zuyd it is the language of instruction for many courses. Many foreign students and expatriates use English as a lingua franca. English is also a mandatory subject in Dutch elementary and secondary schools.

Religion

In 2010–2014, 69.8% of the population of Maastricht regarded themselves as religious. 60.4% of the total population stated an affiliation with the Roman Catholic Church. 13.9% attended a religious ceremony at least once a month.[29]

Economy

Private companies based in Maastricht

- Sappi – South African Pulp and Paper Industry

- Royal Mosa – ceramic tiles

- O-I Manufacturing;– previously Kristalunie Maastricht; glass

- ENCI – cement factory

- BASF – previously Ten Horn; pigments

- Rubber Resources;– previously Radium Foam and Vredestein; rubber recycling

- Hewlett-Packard – previously Indigo, manufacturer of electronic data systems

- Vodafone – mobile phone company

- Q-Park – international operator of parking garages

- DHL – international express mail services

- Teleperformance – contact center services

- Mercedes-Benz – customer contact centre for Europe

- VGZ – health insurance, customer contact centre

- Pie Medical Imaging – cardiovascular quantitative analysis software

- Esaote (former Pie Medical Equipment) – manufacturer of medical and veterinary diagnostic equipment

- BioPartner Centre Maastricht – life sciences spin-off companies

Public institutions

Since the 1980s, a number of European and international institutions have made Maastricht their base. They provide an increasing number of employment opportunities for expats living in the Maastricht area.

- Administration of the Dutch province of Limburg

- Meuse-Rhine Euroregion

- Limburg Development Company LIOF

- Rijksarchief Limburg – archives of the province of Limburg

- Eurocontrol – The European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation

- European Journalism Centre

- European Institute of Public Administration (EIPA)

- European Centre for Development Policy Management (ECDPM)

- European centre for work and society (ECWS)

- Maastricht Centre for Transatlantic Studies (MCTS)

- Expert Centre for Sustainable Business and Development Cooperation (ECSAD)

- Council of European Municipalities and Regions (REGR)

- European Centre for Digital Communication (EC/DC)

- UNU-MERIT

- Maastricht Research School of Economics of TEchnology and ORganization (METEOR)

- Research Institute for Knowledge Systems (RIKS)

- Cicero Foundation (CF)

Culture and tourism

.jpg)

Sights of Maastricht

Maastricht is known in the Netherlands and beyond for its lively squares, narrow streets, and historic buildings. The city has 1,677 national heritage buildings (rijksmonumenten), more than any Dutch city outside Amsterdam. In addition to that there are 3,500 locally listed buildings (gemeentelijke monumenten). The entire city centre is a conservation area (beschermd stadsgezicht). The tourist information office (VVV) is located in the Dinghuis, a medieval courthouse overlooking Grote Staat. Maastricht's main sights include:

- Meuse river, with several parks and promenades along the river, and some interesting bridges:

- Sint Servaasbrug, partly from the 13th century; the oldest bridge in the Netherlands;

- Hoge Brug ("High Bridge"), a modern pedestrian bridge designed by René Greisch;

- City fortifications, including:

- Remnants of the first and second medieval city wall and several towers (13th and 14th centuries);

- Helpoort ("Hell's Gate"), an imposing gate with two towers, built shortly after 1230, the oldest city gate in the Netherlands;

- Waterpoortje ("Little Water Gate"), a medieval gate in Wyck, used for accessing the city from the Meuse, demolished in the 19th century but rebuilt shortly afterwards;

- Hoge Fronten (or: Linie van Du Moulin), remnants of 17th- and 18th-century fortifications with a number of well-preserved bastions and a nearby early 19th-century fortress, Fort Willem I;

- Fort Sint-Pieter ("Fortress Saint Peter"), early 18th-century fortress on the flanks of Mount Saint Peter;

- Casemates, an underground network of tunnels, built as sheltered emplacements for guns and cannons. These tunnels run for several kilometres underneath the city's fortifications, some isolated, others connected to each other. Guided tours are available.

- Binnenstad: inner-city district with pedestrianized shopping streets including Grote and Kleine Staat, and high-end shopping streets Stokstraat and Maastrichter Smedenstraat. The main sights in Maastricht as well as a large number of cafés, pubs and restaurants are centred around the three main squares in Binnenstad:

- Vrijthof, the largest and best-known square in Maastricht, with many well-known pubs and restaurants (including two - one former - gentlemen's clubs). Other sights include:

- Basilica of Saint Servatius, a predominantly Romanesque church with important medieval sculptures (most notably the westwork and east choir sculpted capitals, corbels and reliefs, and the sculpted South Portal or Bergportaal). The tomb of Saint Servatius in the crypt is a favoured place of pilgrimage. The church has an important church treasury;

- Sint-Janskerk, a Gothic church dedicated to Saint John the Baptist, the city's main Protestant church since 1632, adjacent to the Basilica of Saint Servatius, with a distinctive red, limestone tower;

- Spaans Gouvernement ("Spanish Government Building"), a 16th-century former canon's house, also used by the Brabant and Habsburg rulers, now housing the Museum aan het Vrijthof;

- Hoofdwacht ("Main Watch"), a 17th-century military guard house, used for exhibitions;

- Generaalshuis ("General's House"), a Neoclassical mansion, now the city's main theater (Theater aan het Vrijthof).

- Onze Lieve Vrouweplein, a tree-lined square with a number of pavement cafes. Main sights:

- Basilica of Our Lady, an 11th-century church, one of the Netherlands' most significant Romanesque buildings with an important church treasury. Perhaps best known for the shrine of Our Lady, Star of the Sea in an adjacent Gothic chapel;

- Derlon Museumkelder, a small museum with Roman and earlier remains in the basement of Hotel Derlon.

- Markt, the town's market square, completely refurbished in 2006-07 and now virtually traffic free. Sights include:

- The Town Hall, built in the 17th century by Pieter Post and considered one of the highlights of Dutch Baroque architecture. Nearby is Dinghuis, the medieval town hall and courthouse with an early Renaissance façade;

- Mosae Forum, a new shopping centre and civic building designed by Jo Coenen and Bruno Albert. Inside the Mosae Forum parking garage is a small exhibition of Citroën miniature cars;

- Entre Deux, a rebuilt shopping centre in Postmodern style, which has won several international awards.[30] It includes a bookstore located inside a former 13th-century Dominican church. In 2008, British newspaper The Guardian proclaimed this the world's most beautiful bookshop.[31]

- Vrijthof, the largest and best-known square in Maastricht, with many well-known pubs and restaurants (including two - one former - gentlemen's clubs). Other sights include:

- Jekerkwartier, a neighbourhood named after the small river Jeker, which pops up between old houses and remnants of city walls. The western part of the neighbourhood (also called the Latin Quarter of Maastricht), is dominated by university buildings and art schools. Sights include:

- a number of churches and monasteries, some from the Gothic period (the Old Franciscan Church), some from the Renaissance (Faliezustersklooster), some from the Baroque period (Bonnefanten Monastery; Walloon Church, Lutheran Church);

- Maastricht Natural History Museum, a small museum of natural history in a former monastery;

- Grote Looiersstraat ("Great Tanners' Street"), a former canal that was filled in during the 19th century, lined with elegant houses, the city's poorhouse (now part of the university library) and Sint-Maartenshofje, a typically Dutch hofje.

- Kommelkwartier and Statenkwartier, two relatively quiet inner city neighbourhoods with several imposing monasteries and university buildings. The largely Gothic Crosier Monastery is now a five-star hotel.

- Boschstraatkwartier, an upcoming neighbourhood and cultural hotspot in the north of the city centre. Several of the former industrial buildings are being transformed for new uses.

- Sint-Matthiaskerk, a 14th-century parish church dedicated to Saint Matthew;

- Bassin, a restored early 19th-century inner harbor with restaurants and cafés on one side and interesting industrial architecture on the other side.

- Wyck, the old quarter on the right bank of the river Meuse.

- Saint Martin's Church, a Gothic Revival church designed by Pierre Cuypers in 1856;

- Rechtstraat is a street in Wyck, with many historic buildings and a mix of specialty shops, art galleries and restaurants;

- Stationsstraat and Wycker Brugstraat are elegant streets with the majority of the buildings dating from the late 19th century. At the east end of Stationsstraat stands the Maastricht railway station from 1913.

- Céramique, a modern neighbourhood on the site of the former Céramique potteries with a park along the river Meuse (Charles Eyckpark). Now a showcase of architectural highlights:

- Wiebengahal, one of the few remaining industrial monuments in the neighbourhood and an early example of modern architecture in the Netherlands, dating from 1912;

- Bonnefanten Museum by Aldo Rossi;

- Centre Céramique, a public library and exhibition space by Jo Coenen;

- La Fortezza, an office and apartment building by Mario Botta;

- Siza Tower, a residential tower clad with zinc and white marble, by Álvaro Siza Vieira;

- Also buildings by MBM, Cruz y Ortiz, Luigi Snozzi, Aurelio Galfetti, Herman Hertzberger, Wiel Arets, Hubert-Jan Henket, Charles Vandenhove and Bob Van Reeth.

- Sint-Pietersberg ("Mount Saint Peter"): modest hill and nature reserve south of the city, peaking at 171 metres (561 ft) above sea level. It serves as Maastricht's main recreation area and a viewing point. The main sights include:

- Fort Sint-Pieter, an early 18th-century military fortress fully restored in recent years;

- Caves of Maastricht aka Grotten Sint-Pietersberg, an underground network of man-made tunnels ("caves") in limestone quarries. Guided tours are available;

- Slavante, a country pavilion and restaurant on the site of a Franciscan monastery of which parts remain;

- Lichtenberg, a ruined medieval castle keep and a small museum in an adjacent farmstead;

- D'n Observant ("The Observer"), an artificial hilltop, made with the spoils of a nearby quarry, now a nature reserve.

- Fort Sint-Pieter, an early 18th-century military fortress fully restored in recent years;

Museums in Maastricht

- Bonnefanten Museum is the foremost museum for old masters and contemporary fine art in the province of Limburg. The collection features medieval sculpture, early Italian painting, Southern Netherlandish painting, and contemporary art.

- The Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius includes religious artifacts from the 4th to 20th centuries, notably those related to Saint Servatius. Highlights include the shrine, the key and the crosier of Saint Servatius, and the reliquary bust donated by Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma.

- The Treasury of the Basilica of Our Lady contains religious art, textiles, reliquaries, liturgical vessels and other artifacts from the Middle Ages and later periods.

- Derlon Museumkelder is a preserved archeological site in the basement of a hotel with Roman and pre-Roman remains.

- The Maastricht Natural History Museum exhibits collections relating to the geology, paleontology and flora and fauna of Limburg. Highlights in the collection are several fragment of skeletons of Mosasaurs found in a quarry in Mount Saint Peter.

- Museum aan het Vrijthof is a local art and history museum based in the 16th-century Spanish Government building, featuring some period rooms with 17th- and 18th-century furniture, clocks, Maastricht silver, porcelain, glassware and Maastricht pistols, and temporary exhibitions of local artists and designers.

Events and festivals

- Dies natalis, birthday of the University of Maastricht, with procession of university faculty to St. John's Church where honorary degrees are awarded.

- Carnival (Maastrichtian: Vastelaovend) - a traditional three-day festival in the southern part of the Netherlands; in Maastricht mainly outdoors with typical Zaate Herremeniekes (February/March).

- The European Fine Art Fair (TEFAF), the world's leading art and antiques fair (March).

- Amstel Gold Race, an international cycling race which starts in Maastricht (usually April).

- KunstTour, an annual art festival (May).

- European Model United Nations (EuroMUN), an annual international conference in May.

- Stadsprocessie, religious procession with reliquaries of local saints (first Sunday after 13 May).

- Pilgrimage of the Relics (Dutch: Heiligdomsvaart), pilgrimage with relics display and processions dating from the Middle Ages (May/June; once in 7 years; next: 2025).

- Giants' Parade (Dutch: Reuzenstoet), parade of processional giants, mainly from Belgium and France (June; once in 5 years; next: 2024).

- Maastrichts Mooiste, an annual running and walking event (June).

- Fashionclash, international fashion event throughout the city (June).

- Vrijthof concerts by André Rieu and the Johann Strauss Orchestra (July/August).

- Preuvenemint, a large culinary event held on the Vrijthof square (August).

- Inkom, the traditional opening of the academic year and introduction for new students of Maastricht University (August).

- Musica Sacra, a festival of religious (classical) music (September).

- Nederlandse Dansdagen (Netherlands Dance Days), a modern dance festival (October).

- Jazz Maastricht, a jazz festival formerly known as Jeker Jazz (autumn).

- 11de van de 11de (the 11th of the 11th), the official start of the carnival season (11 November).

- Jumping Indoor Maastricht, an international concours hippique (showjumping) (November).

- Magic Maastricht (Magisch Maastricht), a winter-themed funfair and Christmas market held on Vrijthof square and other locations throughout the city (December/January).

Furthermore, the Maastricht Exposition and Congress Centre (MECC) hosts many events throughout the year.

Nature

Parks

There are several city parks and recreational areas in Maastricht:[32]

- Stadspark, the main public park in Maastricht, partly 19th-century, with remnants of the medieval city walls, a branch of the Jeker river, a mini-zoo and several public sculptures (e.g. the statue of d'Artagnan in Aldenhofpark, a 20th-century extension of Stadspark). Other extensions of the park are called Kempland, Henri Hermanspark, Monseigneur Nolenspark and Waldeckpark. From 2014 onwards, the grounds of the former Tapijn military barracks will be gradually added to the park;

- Jekerpark, a new park along the river Jeker, separated from Stadspark by a busy road;

- Frontenpark, a new park west of the city centre, incorporating parts of the fortifications of Maastricht from the 17th to 19th centuries;

- Charles Eykpark, a modern park between the public library and Bonnefanten Museum on the east bank of the Meuse river, designed in the late 1990s by Swedish landscape architect Gunnar Martinsson.

- Griendpark, a modern park on the east bank of the river with an inline-skating and skateboarding course.

- Geusseltpark in eastern Maastricht and J.J. van de Vennepark in western Maastricht, both with elaborate sports facilities.

Natural areas

- The Meuse river and its green banks in outlying areas. In the northern areas around Itteren and Borgharen 'new nature' is being created in combination with river protection measures and gravel mining.[33]

- Pietersplas, an artificial lake between Maastricht and Gronsveld that was the result of gravel pits on the banks of the Meuse river. There is a beach on the northern slope of the lake and a marina near Castle Hoogenweerth. The eastern riverbed between Pietersplas and the provincial government building is a nature reserve (Kleine Weerd).

- The Jeker Valley, along the river Jeker, starts near the city centre in Stadspark and leads via Jekerpark to an area with green meadows, fertile fields, some vineyards on the slopes of Cannerberg, several water mills and Château Neercanne, and continues further south into Belgium.

- The green flanks of Mount Saint Peter, including many footpaths.[34]

- Dousberg and Zouwdal, a modest hill and valley surrounded by urban development on the western edge of the city, partly in Belgium. A large part of the hill is now in use as an international golf course (Golfclub Maastricht).[35]

- Landgoederenzone, an extended area in the northeast of Maastricht (partly in Meerssen) consisting of around fifteen country estates, such as Severen, Geusselt, Bethlehem, Mariënwaard, Kruisdonk, Vaeshartelt, Meerssenhoven, Borgharen and Hartelstein. Some of the castles, villas and stately homes are surrounded by industrial areas or quarries.

- Bike paths through agricultural areas in several outlying quarters (like "Biesland" and "Wolder").

Sports

- In football, Maastricht is represented by MVV Maastricht (Dutch: Maatschappelijke Voetbal Vereniging Maastricht), who (as of the 2016–2017 season) play in the Dutch first division of the national competition (which is the second league after the Eredivisie league). MVV's home is the Geusselt stadium near the A2 highway.

- Maastricht is also home to the Maastricht Wildcats, an American Football League team and member of the AFBN (American Football Bond Nederland).

- Since 1998, Maastricht has been the traditional starting place of the annual Amstel Gold Race, the only Dutch cycling classic. For several years the race also finished in Maastricht, but since 2002 the finale has been in the municipality of Valkenburg. Tom Dumoulin was born in Maastricht.

- Since 2000, Maastricht has been the first city in the Netherlands with a Lacrosse team. The Student Sport Association "Maaslax" is closely linked to Maastricht University and a member of the NLB (Nederlandse Lacrosse Bond).

Politics

City council

| Parties | 2006 | 2010 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senioren Partij Maastricht (SPM) | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| CDA | 7 (6) | 7 | 5 |

| PvdA | 13 | 7 | 5 |

| D66 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| SP | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| GroenLinks | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| VVD | 4 (3) | 4 | 3 |

| TON / Partij Veilig Maastricht (PVM) | - | 2 | 3 |

| Stadsbelangen Mestreech (SBM) | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Liberale Partij Maastricht (LPM) | (1) | 1 | 1 |

| Christelijke Volkspartij (Maastricht) (CVP) | (1) | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 39 | 39 | 39 |

The municipal government of Maastricht consists of a city council, a mayor and a number of aldermen. The city council, a 39-member legislative body directly elected for four years, appoints the aldermen on the basis of a coalition agreement between two or more parties after each election. The 2006 municipal elections in the Netherlands were, as often, dominated by national politics and led to a shift from right to left throughout the country. In Maastricht, the traditional broad governing coalition of Christian Democrats (CDA), Labour (PvdA), Greens (GreenLeft) and Liberals (VVD) was replaced by a centre-left coalition of Labour, Christian Democrats and Greens. Two Labour aldermen were appointed, along with one Christian Democrat and one Green alderman. Due to internal disagreements, one of the VVD council members left the party in 2005 and formed a new liberal group in 2006 (Liberalen Maastricht). The other opposition parties in the current city council are the Socialist Party (SP), the Democrats (D66) and two local parties (Stadsbelangen Mestreech (SBM) and the Seniorenpartij).

Aldermen and mayors

The aldermen and the mayor make up the executive branch of the municipal government. After the previous mayor, Gerd Leers (CDA), decided to step down in January 2010 following the 'Bulgarian Villa' affair, an affair concerning a holiday villa project in Byala, Bulgaria, in which the mayor was alleged to have been involved in shady deals to raise the value of villas he had ownership of. Up until July 1, 2015 the mayor of Maastricht was Onno Hoes, a Liberal (VVD), the only male mayor in the country, who officially was married to a male person. In 2013 Hoes was the subject of some political commotion, after facts had been disclosed about intimate affairs with several other male persons. The affair had no consequences for his political career.[36] Because of a new affair in 2014 Hoes eventually stepped down.[37]

Since July 1, 2015 the current mayor of Maastricht has been Annemarie Penn-te Strake.[38] Penn is independent and serves no political party, although her husband is a former[39] chairman of the Maastricht Seniorenpartij.[40] She has served for the Dutch judicial system for many years in many different positions. During her tenure as mayor she still serves as attorney general.[41]

Cannabis

One controversial issue which has dominated Maastricht politics for many years and which has also affected national and international politics, is the city's approach to soft drugs. Under the pragmatic Dutch soft drug policy, a policy of non-enforcement, individuals may buy and use cannabis from 'coffeeshops' (cannabis bars) under certain conditions. Maastricht, like many other border towns, has seen a growing influx of 'drug tourists', mainly young people from Belgium, France and Germany, who provide a large amount of revenue for the coffeeshops (around 13) in the city centre. The city government, most notably ex-mayor Leers, have been actively promoting drug policy reform in order to deal with its negative side effects.

One of the proposals, known as the 'Coffee Corner Plan', proposed by then-mayor Leers and supported unanimously by the city council in 2008, was to relocate the coffeeshops from the city centre to the outskirts of the town (in some cases near the national Dutch-Belgian border).[42] The purpose of this plan was to reduce the impact of drug tourism on the city centre, such as parking problems and the illegal sale of hard drugs in the vicinity of the coffeeshops, and to monitor the sale and use of cannabis more closely in areas away from the crowded city centre. The Coffee Corner Plan, however, has met with fierce opposition from neighbouring municipalities (some in Belgium) and from members of the Dutch and Belgian parliament. The plan has been the subject of various legal challenges and has not been carried out up to this date (2014).

On 16 December 2010, the Court of Justice of the European Union upheld a local Maastricht ban on the sale of cannabis to foreign tourists, restricting entrance to coffeeshops to residents of Maastricht.[43] The ban did not affect scientific or medical usage. In 2011, the Dutch government introduced a similar national system, the wietpas ("cannabis pass"), restricting access to Dutch coffeeshops to residents of the Netherlands. After protests from local mayors about the difficulty of implementing the issuing of wietpasses, Dutch parliament in 2012 agreed to replace the pass by any proof of residency.[44] The new system has led to a slight reduction in drug tourism to cannabis shops in Maastricht but at the same time to an increase of drug dealing on the street.

Transport

By car

Maastricht is served by the A2 and A79 motorways. The city can be reached from Brussels and Cologne in approximately one hour and from Amsterdam in about two and a half hours.

The A2 motorway runs through Maastricht in a double-decked tunnel. Before 2016, the A2 motorway ran through the city; heavily congested, it caused air pollution in the urban area. Construction of a two-level tunnel designed to solve these problems started in 2011 and was opened (in stages) by December 2016.[45]

In spite of several large underground car parks, parking in the city centre forms a major problem during weekends and bank holidays because of the large numbers of visitors. Parking fees are deliberately high to make visitors to use public transport or park and ride facilities away from the centre.

By train

Maastricht is served by three rail operators, all of which call at the main Maastricht railway station near the centre and two of which call at the smaller Maastricht Randwyck, near the business and university district. Only Arriva also calls at Maastricht Noord, which opened in 2013. Intercity trains northwards to Amsterdam, Eindhoven, Den Bosch and Utrecht are operated by Dutch Railways. The National Railway Company of Belgium runs south to Liège in Belgium. The line to Heerlen, Valkenburg and Kerkrade is operated by Arriva. The former railway to Aachen was closed down in the 1980s. A small section of the old westbound railway to Hasselt (Belgium) was restored in recent years and will be used as a modern tramline, scheduled to open in 2023.[46]

By tram

The Dutch and Flanders governments reached an agreement in 2014 to build a new tram route, the Hasselt – Maastricht tramway, as part of the larger Spartacus scheme. It was scheduled to take three years, from 2015 to 2018, and to cost €283 million. However, the planning process has been heavily delayed, and as of 2018, construction has not yet started. The tram is now scheduled to be operating in 2024.[47] When completed, the tram will carry passengers from Maastricht city centre to Hasselt city centre in 30 minutes. It will be operated by the Belgian transport company De Lijn, with 2 scheduled stops in Maastricht and another 10 in Flanders.[48]

By bus

Regular bus lines connect the city centre, outer areas, business districts and railway stations. The regional Arriva bus network extends to most parts of South Limburg and Aachen in Germany. Regional buses by De Lijn connect Maastricht with Hasselt, Tongeren and Maasmechelen, and one bus connects Maastricht with Liège, operated by TEC.

By air

Maastricht is served by the nearby Maastricht Aachen Airport (IATA: MST, ICAO: EHBK), in nearby Beek, and it is informally referred to by that name. The airport is located about 10 kilometres (6 miles) north of the city centre. The airport is served by Corendon Dutch Airlines and Ryanair which operate scheduled flights to destinations around the Mediterranean, the Canary Islands and North-Africa . There are also charter flights to Lourdes which are operated by Enter Air.

By boat

Maastricht has a river port (Beatrixhaven) and is connected by water with Belgium and the rest of the Netherlands through the river Meuse, the Juliana Canal, the Albert Canal and the Zuid-Willemsvaart. Although there are no regular boat connections to other cities, various organized boat trips for tourists connect Maastricht with Belgium cities such as Liège.

Distances to other cities

These distances are as the crow flies and so do not represent actual overland distances.

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Education

Secondary education

- Bernard Lievegoedschool (Anthroposophical education)

- Bonnefantencollege

- Porta Mosana College

- Sint-Maartenscollege

- United World College Maastricht

Tertiary education

- Maastricht University (Dutch: Universiteit Maastricht or UM) including:

- Maastricht School of Management

- Teikyo University (Maastricht campus closed in 2007)

- Zuyd University of Applied Sciences (Dutch: Hogeschool Zuyd, also has departments in Sittard and Heerlen) including:

- Academy for Dramatic Arts Maastricht (Dutch: Toneelacademie Maastricht)

- School of Fine Arts Maastricht (Dutch: Academie Beeldende Kunsten Maastricht)

- Maastricht Academy of Music (Dutch: Conservatorium Maastricht)

- Academy of architecture

- Teachers training college

- Faculty of International Business and Communication

- Maastricht Hotel Management School

Other

- Jan Van Eyck Academie - post-academic art institute

- Berlitz Language School Maastricht

- Talenacademie Nederland

International relations

Twin towns

Maastricht is twinned with:

Other relations

Notable people

Born in Maastricht

- Jean-Eugène-Charles Alberti (1777 – after 1843) – painter

- Henri Arends (1921–1993) – conductor

- Doris Baaten (born 1956) – voice actress

- Mieke de Boer (born 1980) – female darts player

- Alphons Boosten (1893–1951) – architect

- Theo Bovens (born 1959) – politician

- Joseph Bruyère (born 1948) – Belgian cyclist

- Jean-Baptiste Coclers (1696–1772) – painter

- Louis Bernard Coclers (1740–1817) – painter

- Peter Debye (1884–1966) – Nobel prize winning chemist

- Tom Dumoulin (born 1990) – cyclist, Giro d'Italia winner

- Hendrick Fromantiou (1633/4 – after 1693) – still life painter

- Joop Haex (1911–2002) – politician

- André Henri Constant van Hasselt (1806–1874) – French-writing poet

- Hubert Hermans (born 1937) – psychologist and creator of Dialogical Self Theory

- Pieter van den Hoogenband (born 1978) – swimmer and a triple Olympic champion

- Pierre Kemp (1886–1967) – poet

- Sjeng Kerbusch (1947–1991) – behavior geneticist

- Mathieu Kessels (1784–1836) – sculptor

- Lambert of Maastricht (c. 636 – c. 705) – bishop, saint

- Eric van der Luer (born 1965) – footballer, football manager

- Pierre Lyonnet (1708–1789) – naturalist, cryptographer, engraver

- Félix de Mérode (1791–1857) – politician, writer

- Jan Pieter Minckeleers (1748–1824) – scientist and inventor of coal gas lighting

- Bram Moszkowicz (born 1960) – ex-barrister

- Benny Neyman (1951–2008) – singer of popular songs

- Tom Nijssen (born 1964) – tennis player

- Jacques Ogg (born 1948) – harpsichordist

- Henrietta d'Oultremont (1792–1864) – second wife of William I of the Netherlands

- Jan Peumans (born 1951) – Belgian politician

- Guido Pieters (born 1948) – film director

- Dick Raaymakers (1930–2013) – composer, theater maker

- Prince Rajcomar (born 1985) – football player

- Louis Regout (1861–1915) – politician

- André Rieu (born 1949) – violinist, conductor and composer

- Fred Rompelberg (born 1945) – cyclist, former world record holder

- Louis Rutten (1884-1946) – Dutch geologist

- Henri Sarolea (1844–1900) – railway entrepreneur and contractor

- Bryan Smeets (born 1992) - Football player

- Hubert Soudant (born 1946) – conductor

- Victor de Stuers (1843–1916) – politician, monument conservationist

- Jac. P. Thijsse (1865–1945) – botanist, conservationist

- Frans Timmermans (born 1961) – politician

- Johann Friedrich August Tischbein (1750–1812) – portrait painter

- Maxime Verhagen (born 1956) – politician

- Hubert Vos (1855–1935) – painter

- Ad Wijnands (born 1959) – cyclist, Tour de France stage winner

- Jeroen Willems (1962–2012) – actor, singer

- Henri Winkelman (1876–1952) – general

- Danny Wintjens (born 1983) – football goalkeeper

- Boudewijn Zenden (born 1976) – football player

- Kim Zwarts (born 1955) – photographer

Residing in Maastricht

- Jo Bonfrere (born 1946) – football player

- Willy Brokamp (born 1946) – football player

- Jeroen Brouwers (born 1940) – writer, journalist

- Gondulph of Maastricht (c. 524 – c. 607) – bishop, saint

- Theo Hiddema (born 1944) – lawyer

- Willem Hofhuizen (1915–1986) – painter

- Monulph of Maastricht (6th century) – bishop, saint

- Max Moszkowicz (born 1926) – lawyer

- Servatius of Maastricht (4th century – 384?) – bishop, saint

- Jan van Steffeswert (15th/16th century) – sculptor, wood carver

- Aert van Tricht (15th/16th century) – metal caster

- Henric van Veldeke (12th century) – poet, hagiographer

Local anthem

In 2002 the municipal government officially adopted a local anthem (Limburgish (Maastrichtian variant): Mestreechs Volksleed, Dutch: Maastrichts Volkslied) composed of lyrics in Maastrichtian. The theme was originally written by Ciprian Porumbescu (1853–1883).[49]

Gallery

Meuse River

Meuse River

Dinghuis

Dinghuis- Townhall

Mosae Forum

Mosae Forum Saint Servatius Basilica

Saint Servatius Basilica Onze-Lieve-Vrouweplein

Onze-Lieve-Vrouweplein

Lang Grachtje

Lang Grachtje Helpoort ("Hell's Gate")

Helpoort ("Hell's Gate") Pater Vink Tower

Pater Vink Tower Bastion Haet ende Nijt

Bastion Haet ende Nijt Stadspark

Stadspark Jeker river

Jeker river Bassin harbour

Bassin harbour Train station, Wyck

Train station, Wyck Stationsplein, Wyck

Stationsplein, Wyck Hoeg Brögk

Hoeg Brögk Charles Eyckpark, Céramique

Charles Eyckpark, Céramique- Public library, Céramique

Fortress Sint Pieter

Fortress Sint Pieter- View from Slavante

- Castle ruin Lichtenberg

Huis de Torentjes

Huis de Torentjes- ENCI quarry

View on Cannerberg

View on Cannerberg

See also

- Jewish inhabitants of Maastricht

- Maastricht Treaty

- Treaty of Maastricht (1843)

- The Maastrichtian Age, which marks the end of the Cretaceous Period and Mesozoic Era of geological time

References

- Notes

- "Mrs. Annemarie Penn-te Strake" [Mr. Annemarie Penn-te Strake] (in Dutch). Gemeente Maastricht. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Kerncijfers wijken en buurten" [Key figures for neighbourhoods]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 2 July 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Postcodetool for 6211DW". Actueel Hoogtebestand Nederland (in Dutch). Het Waterschapshuis. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 1 January 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- "Bevolkingsontwikkeling; regio per maand" [Population growth; regions per month]. CBS Statline (in Dutch). CBS. 26 June 2014. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- Including the Belgian municipalities of Lanaken, Riemst and Maasmechelen to the west and Visé to the south.

- Basically, the metropolitan areas of Maastricht, Liège, Hasselt-Genk, Sittard-Geleen, Heerlen-Kerkrade and Aachen-Düren constitute the densely populated urban core of the Meuse–Rhine Euroregion.

- "Maastricht". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "Maastricht" (US) and "Maastricht". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "Maastricht". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- Local pronunciation: [maːˈstʀɪx̟t].

- "Zicht op Maastricht". zichtopmaastricht.nl. Retrieved 2012-08-19.

- "The Economist ''Charlemagne: Return to Maastricht'' Oct 8th 2011". Economist.com. 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- MAETN (1999). "diktyo". classic-web.archive.org. Archived from the original on October 22, 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2011.

- As Treiectinsem urbem, "the city of Trajectum", in Gregory of Tours, Historia Francorum, 2, 5 Archived 2015-03-16 at the Wayback Machine (late 6th ct.). M. Gysseling, Toponymisch Woordenboek van België, Nederland, Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en West-Duitsland (vóór 1226) (Tongeren, 1960) p. 646.

- (Gysseling 1960, pp. 646–647)

- Bredero, Adriaan H. (1994), Christendom and Christianity in the Middle Ages: The Relations Between Religion, Church, and Society, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, p. 352, ISBN 978-0-8028-4992-2.

- About 77% of Maastricht's relatively small Jewish community of 505 members did not survive the war. P.J.H. Ubachs & I.M.H. Evers (2005): Historische Encyclopedie Maastricht, pp. 256-257. Walburg Pers, Zutphen. ISBN 90-5730-399-X.

- Gnesotto, N. (1992). European union after Minsk and Maastricht. International Affairs. 68(2), 223-232.

- Maastricht Van onze verslaggever. "Coffee Corner: Dagblad de Limburger". Limburger.nl. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- "06380: Maastricht Airport Zuid Limburg (Netherlands)". OGIMET. 2019-07-25. Retrieved 2019-07-2019. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "Klimaattabel Maastricht, langjarige gemiddelden, tijdvak 1981–2010" (PDF) (in Dutch). Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- "Klimaattabel Maastricht, langjarige extremen, tijdvak 1971–2000" (PDF) (in Dutch). Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- "Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, nationaliteit en regio, 1 januari (in Dutch)". Bevolking; geslacht, leeftijd, nationaliteit en regio, 1 januari. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 2014: 1. 24 October 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "Bevolking op 1 januari; leeftijd, geboorteland en regio (in Dutch)". Bevolking op 1 januari; leeftijd, geboorteland en regio. Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. 201w: 1. 17 July 2013. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- "Kerkelijkheid en kerkbezoek, 2010/2013". Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

- Gussenhoven, C. & Aarts, F. (1999). "The dialect of Maastricht" (PDF). University of Nijmegen, Centre for Language Studies. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-12. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- Kessels-van der Heijde, Maria (2002). Maastricht, Maestricht, Mestreech. Hilversum, Netherlands: Uitgeverij Verloren. pp. 11–12. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- 'Religie en kerkbezoek naar gemeente 2010-2014', on website cbs.nl, 13 May 2015 (download Excel file).

- "Entre Deux". Entredeux.nl. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- "Top shelves". The Guardian. London. 2008-03-03. Retrieved 2012-05-23.

- "Category:Parks in Maastricht - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org.

- "Category:Meuse River in Maastricht - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org.

- "Category:Sint Pietersberg - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org.

- "Category:Dousberg - Wikimedia Commons". commons.wikimedia.org.

- "Onno Hoes mag blijven". Telegraaf. 19 December 2013.

- Grindstad, Ingrid. "Maastricht mayor Hoes resigns amidst sex smear campaign", NL Times, Amsterdam, 10 December 2014. Retrieved on 10 December 2014.

- "Annemarie Penn geïnstalleerd als burgemeester Maastricht". 1 July 2015.

- "Olaf Penn stopt bij Senioren Partij Maastricht". 1Limburg. 2015-04-23. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- "Annemarie Penn nieuwe burgemeester Maastricht - NU - Het laatste nieuws het eerst op NU.nl". www.nu.nl.

- "Mr. J.M. Penn-te Strake - Openbaar Ministerie". 3 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Cannabis Cafes Get Nudge to Fringes of a Dutch City, The New York Times, 20 August 2006.

- "Marc Michel Josemans v. Burgemeester van Maastricht, case C‑137/09". Court of Justice of the European Union. December 16, 2010. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012.

- "Eindhoven joins opposition to cannabis pass system". Dutchnews.nl. February 9, 2011.

- "A2maastricht.nl - Homepage A2 Maastricht". www.a2maastricht.nl. Archived from the original on 2010-05-03. Retrieved 2010-07-31.

- Redactie/HBVL. "Sneltram tussen Maastricht en Hasselt gaat in 2023 rijden". Dagblad de Limburger. Retrieved 2017-10-11.

- "Waar staan we nu?". Tram Maastricht-Hasselt.

- Blyth, Derek. "Hasselt to Maastricht high-speed tram link by 2018". flanderstoday.eu. Retrieved 2014-03-27.

- Municipality of Maastricht (2008). "Municipality of Maastricht: Maastrichts Volkslied". N.A. Maastricht. Retrieved 2009-08-05.

- Literature

- Lourens, Piet; Lucassen, Jan (1997). Inwonertallen van Nederlandse steden ca. 1300–1800. Amsterdam: NEHA. ISBN 9057420082.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

.jpg)