Basilica of Our Lady, Maastricht

The Basilica of Our Lady (Dutch: Basiliek van Onze-Lieve-Vrouw; Limburgish/Maastrichtian [colloquial]: Slevrouwe) is a Romanesque church in the historic center of Maastricht, Netherlands. The church is dedicated to Our Lady of the Assumption (Dutch: Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-Tenhemelopneming) and is a Roman Catholic parish church in the Diocese of Roermond. The church is often referred to as the Star of the Sea (Dutch: Sterre der Zee), after the church's main devotion, Our Lady, Star of the Sea.

| Basilica of Our Lady | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica |

| Location | |

| Location | Onze Lieve Vrouweplein, Maastricht, Netherlands |

| Geographic coordinates | 50°50′51″N 5°41′37″E |

| Architecture | |

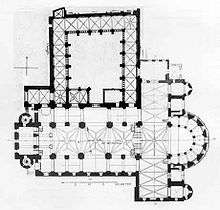

| Type | Basilica with transept and pseudo-transepts |

| Style | Romanesque |

| Website | |

| www | |

History

The present-day church is probably not the first church that was built on this site. However, since no archeological research has ever been carried out inside the building, nothing certain can be said about this. The church's site, inside the Roman castrum and adjacent to a religious shrine dedicated to the god Jupiter, suggests that the site was once occupied by a Roman temple. It is not unlikely that the town's first church was built here and that this church in the 4th or 5th century became the cathedral of the diocese of Tongeren-Maastricht.

Some time before the year 1100 the church became a collegiate church, run by a college of canons. The canons were appointed by the prince-bishop of Liège. The provosts were chosen from the chapter of St. Lambert's Cathedral, Liège. The chapter of Our Lady's had around 20 canons, which made it a middle-sized chapter in the diocese of Liège. Until the end of the chapter in 1798 it maintained its strong ties with Liège. Parishioners of Our Lady's were identified in old documents as belonging to the Familia Sancti Lamberti.[1] It is clear that the chapter of Saint Servatius was the more powerful institution in Maastricht, with strong ties to the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire, but throughout the Middle Ages the two churches remained rivals.[2]

.jpg)

Most of the present church was built in the 11th and 12th centuries. Construction of the imposing westwork started shortly after 1000 AD. In the 13th century the nave received Gothic vaults. Around 1200 the canons abandoned their communal lifestyle, after which canons' houses were built in the vicinity of the church. In the 14th century a parish church was built next to the collegiate church, so the main building could be reserved for the canons' religious duties. Of this parish church, dedicated to Saint Nicolas, very little remains as it was demolished in 1838. Apart from Saint Nicholas Church, the parish made use of three other chapels dedicated to Saint Hilarius, Saint Evergislus, and Saint Mary Minor.[3] In the mid-16th century the present late Gothic cloisters replaced the earlier cloisters.

After the incorporation of Maastricht in the French First Republic in 1794, the town's religious institutions were dissolved (1798). Many of the church treasures were lost during this period. The church and cloisters were used as a blacksmith shop and stables by the military garrison. This situation continued until 1837 when the church was restored to the religious practice. This coincided with the demolishing of Saint Nicholas Church and the transfer of the parish to Our Lady's.

From 1887 to 1917 the church was thoroughly restored by well-known Dutch architect Pierre Cuypers. Cuypers basically removed everything that did not fit his ideal of a Romanesque church. Parts of the east choir, the two choir towers, and the south aisle were almost entirely rebuilt.

The church was elevated to the rank of minor basilica by Pope Pius XI on 20 February 1933.[4]

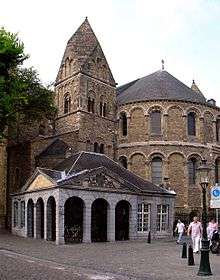

Description exterior

The building is largely Romanesque in style and is considered an important example of the Mosan group of churches that are characterized by massive westworks and pseudo-transepts. Our Lady's in Maastricht indeed has a tall, massive westwork and two pseudo-transepts on each side. The westwork, built of carbonic sandstone, dates from the early 11th century and is flanked by two narrow towers with marlstone turrets. Some spolia, probably from the former Roman castrum of Maastricht, were used on the lower parts of the westwork. The nave with its transept and pseudo-transepts largely dates from the second half of the 11th century.

The church has two choirs and two crypts. The east choir dates from the 12th century and is decorated with carved Romanesque capitals (several of which are 19th-century copies). The east crypt is a century older. During the building campaign the original plan for the eastern part of the church was abandoned and a new scheme, based on the newly finished choir of St. Lambert's Cathedral, Liège, adopted.[5] The current, heavily-restored choir towers are roofed with Rhenish helms of stone rather than shingling. One of the towers, named after Saint Barbara, was used for storage of the city archives and the church treasury.

A 13th-century Gothic portal, rebuilt in the 15th century, provides access to the church from Onze Lieve Vrouweplein. It is also the entrance of the so-called Mérode chapel (or Star of the Sea chapel).

Westwork

Westwork Roman spolia westwork

Roman spolia westwork Entrance Mérode chapel

Entrance Mérode chapel Apse and St. Barbara tower

Apse and St. Barbara tower

Description interior

Although the interior of the church underwent many changes throughout the centuries, it has an 'authentic' Romanesque feel to it. This is largely due to the restoration ideas of the architect Pierre Cuypers, who had several of the larger Gothic windows replaced by small Romanesque windows, thus creating a darker, 'mystical' atmosphere. Cuypers also removed the white plastering of the late Baroque period and had several altars built in a Romanesque or Gothic Revival style. Despite all these changes, the turbulent history of the building is still legible. Some murals dating from the Middle Ages have survived (including one of Saint Catherine from the 14th century). A mural on a pillar of Saint Christopher and the Infant Jesus dates from 1571. The large ceiling painting in the choir is Neo-Romanesque and dates from the Cuypers restoration. All stained glass windows are from the 19th or 20th century.

The furnishing of the church interior has followed the fashion of the time but suffered badly during the years of desecration (1798-1837). In 1380 the church had 33 altars[6] but most of the medieval church inventory got lost in the turbulence that followed the arrival of the French in 1794. A precious baptismal font by the Maastricht metalworker Aert van Tricht (c. 1500) survived but was stripped of most of its ornaments. Several Baroque confessionals and a richly carved pulpit were taken over from a former nearby Jesuit church. The 18th-century Baroque altar, now in the southern transept, is from the former Church of Saint Nicholas. The large pipe organ was built in 1652 by André Severin.

Among the works of art owned by the church are a wood panel of The dream of Jacob (Flemish, c. 1500-1550), a large canvas with the Holy Family (Southern Netherlands, c. 1600), a large painting of the Crucifixion (Southern Netherlands, 17th century), two paintings attributed to Erasmus Quellinus II, one of Saint Cecilia and one of Saint Agnes (17th century), a 14th-century German Pieta, two 15th-century statues of the Virgin Mary (including the famous one in the Star of the Sea chapel), an Anna selbdritt and a Saint Christopher, both attributed to the Maastricht sculptor Jan van Steffeswert (c. 1500).

The architectural sculpture in the interior of the Basilica of Our Lady belongs to the highlights of Mosan art. The 20 highly symbolic capitals in the choir ambulatory depict scenes from the Old Testament, as well as various kinds of animals, monsters, birds, naked or scarcely dressed humans entangled in foliage, and humans fighting with animals. One capital in particular is famous as it was signed 'Heimo', probably by its maker who may also be represented on it, handing over a capital to the virgin Mary. The carved capitals and corbels of the choir gallery, as well as the capitals in the nave, are of a slightly later date and less vivid, depicting mainly foliage with some human and animal figures.[7] Most of the carved capitals, as well as some important reliefs elsewhere in the church, date from the second half of the 12th century. A close relationship has been established between the Romanesque sculpture in Our Lady's and that in the Basilica of Saint Servatius in Maastricht, the Church of St Peter in Utrecht and the Schwarzrheindorf double chapel in Bonn.[8]

Interior towards the west

Interior towards the west East choir with ambulatory and gallery

East choir with ambulatory and gallery Capitals depicting Old Testament scenes

Capitals depicting Old Testament scenes Composite capital with Esau and Jacob

Composite capital with Esau and Jacob

Cloisters and Star of the Sea chapel

.jpg)

Access to the cloisters, which enclose a garden, is through the church. The current cloisters were built in marlstone in late Gothic style with some Renaissance elements in 1558/59. They replaced the older Romanesque cloisters, of which some capitals have survived in the collection of the Bonnefantenmuseum.[9] The floor of the cloisters is paved with monumental grave stones, some of them from the demolished Saint Nicholas Church. In 1910 a tower of the Roman castrum was found in the cloister garden.

For many people the main attraction of the Basilica of Our Lady is the miraculous statue of Our Lady, Star of the Sea. This 15th-century wooden statue was originally housed in a nearby Franciscan monastery. In 1801 it was moved to the former parish church of Saint Nicholas, adjacent to Our Lady's. After the closure of that church in 1837, the statue moved to Our Lady's. In 1903 it was placed in a Gothic chapel near the main entrance where it remains today and where it is daily visited by hundreds of worshipers. Twice a year it is being carried around town in the city's religious processions.

Late Gothic cloisters and cloister yard

Late Gothic cloisters and cloister yard Detail window with perron (emblem of Liège)

Detail window with perron (emblem of Liège) Interior cloisters with gravestones

Interior cloisters with gravestones Star of the Sea chapel - view from the cloister yard

Star of the Sea chapel - view from the cloister yard

Treasury

The Basilica of our Lady possesses an important historical church treasure consisting of relics, reliquaries, textiles and liturgical objects. From the 14th century onwards it had a separate treasury room (Dutch: schatkamer), which at one point was located in the Tower of Saint Barbara (also the church's archives). It is believed that the choir gallery of Our Lady's was specifically built in the 12th century for the public showing of the recently acquired relics from Constantinople.[10] During the Middle Ages great rivalry existed between Maastricht's two religious chapters. At several occasions the chapter of Saint Servatius complained about the fact that the canons at Our Lady's showed their relics in the open air, which only St Servatius' was allowed to do. The relics display, especially at the time of the Septennial Pilgrimage (Dutch: Heiligdomsvaart), drew large numbers of pilgrims from all over Europe, bringing in revenue for the churches.[11]

Today the church treasure is only a fraction of what it once was. Many gold and silver objects were melted down in order to pay for war taxes during the tumultuous period after the French conquest of Maastricht in 1794. Other pieces were sold for personal gain or given away. Even as late as 1837, the church lost two of its most precious possessions out of ignorance. A 10th-century reliquary in the shape of a patriarchal cross, allegedly containing the largest particle of the True Cross, and the so-called "pectoral cross of Constantine" (both originating from Constantinople and probably taken to Maastricht by crusaders) were given away by a former canon and are now in the treasury of the St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican City.[12] Two copper-gilt reliefs depicting angels are now in the Treasury of the Basilica of Saint Servatius.[13] In some cases the reliquaries were lost but the content (the relics) was saved. This is the case with the so-called "Virgin's Girdle". Of the original silver statues of the Virgin and two angels only a silver tube with the girdle survived.[14]

The treasure of the basilica of Our Lady as it is today consists of reliquary boxes, cases or busts made of (gilded) silver or copper, silvered lead, brass, ivory, horn, bone and wood; chalices, patens, monstrances and other liturgical implements made of silver, silver-gilt, brass or tin; ecclesiastical vestments and ancient fabrics used for wrapping relics; antique books and manuscripts; paintings, prints and sculptures; and some archeological finds. The highlights are:

- Silver reliquary for the "girdle of the Virgin Mary" (Maastricht?, 14th century, incomplete)

- Tower belonging to a silver statue of Saint Barbara (Maastricht?, 16th century, the statue was melted down in 1795)[15]

- Three ivory reliquary chests (southern Italy or Spain, 12th or 13th century)[16]

- Three reliquary horns: one made of cattle horn with silvered lead furnishings (Scandinavia, 10th century), one of ivory with red copper furnishings (Southern Europe, 14th or 15th century) and one made of wood (Germany, 15th century)[17]

- Two silver ostensoria (Meuse-Rhine, 14th and 15th centuries)[18]

- Red velvet bursa or reliquary purse (France, 15th century). In 1913 there were 8 textile bursas in the treasury (some 13th century); all but one lost.[19]

- So-called "Robe of Saint Lambert" (Central Asia, 10th-13th centuries?)[20]

Furthermore, the treasury is home to a collection of devotional objects (crucifixes, statuettes, rosaries, scapulars, pilgrim badges, and In memoriam cards) belonging to the foundation "Santjes en Kantjes".

- Reliquary horn (Scandinavia, 10th century)

Ivory collection (12th-15th century)

Ivory collection (12th-15th century) Monstrances and candlesticks (17th-18th century)

Monstrances and candlesticks (17th-18th century) So-called "Robe of Saint Lambert"

So-called "Robe of Saint Lambert"

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Onze-Lieve-Vrouwebasiliek (Maastricht). |

- www.sterre-der-zee.nl (official website, largely in Dutch)

Sources and references

- (in French) Bock, F., & M. Willemsen (1873): Antiquitées Sacrées conservées dans les Anciennes Collégiales de S.Servais et de Notre-Dame à Maestricht. Publisher unknown, Maastricht

- (in Dutch) Bosman, A.F.W. (1990): De Onze Lieve Vrouwekerk te Maastricht. Bouwgeschiedenis en historische betekenis van de oostpartij. Clavis Kunsthistorische Monografieën, Volume IX. Walburg Pers, Zutphen. ISBN 906011-688-7

- Hartog, E. den (2002): Romanesque Sculpture in Maastricht. Bonnefantenmuseum, Maastricht. ISBN 9072251318

- (in Dutch) Haye, R. de la (2005): Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk I (Maastrichts Silhouet #62). Stichting Historische Reeks Maastricht, Maastricht. ISBN 905842023X

- (in Dutch) Koldeweij, A.M. & P.M.L. van Vlijmen (ed.) (1985): Schatkamers uit het Zuiden. Rijksmuseum Het Catharijneconvent, Utrecht. ISBN 9071240029

- (in Dutch) Kreek, M.L. de (1994): De kerkschat van het Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekapittel te Maastricht. Clavis Kunsthistorische Monografieën deel XIV. Clavis/Architectura & Natura Pers, Utrecht/Amsterdam/Zutphen. ISBN 90-71570-44-4

- (in Dutch) Nispen tot Sevenaer, E.O.M. van (1926/1974): De monumenten in de gemeente Maastricht, Part 2. Arnhem (online text)

- (in Dutch) Panhuysen, T.A.S.M. (1984): Maastricht staat op zijn verleden. Stichting Historische Reeks Maastricht. ISBN 9070356198

- (in Dutch) Sprenger, W. (1912): 'Geschiedenis der restauratie van O.L. Vrouwe kerk te Maastricht'. In: De Maasgouw, pp. 59, 60

- (in Dutch) Term, J. van, & J. Nelissen (1979): Kerken van Maastricht. Vroom & Dreesmann, Maastricht

- (in Dutch) Timmers, J.J.M. (1971): De kunst van het Maasland. Maaslandse Monografieën (large format), Part 1. Van Gorcum, Assen. ISBN 90-232-0726-2

- (in Dutch) Ubachs, P.J.H., & I.M.H. Evers (2005): Historische Encyclopedie Maastricht. Walburg Pers, Zutphen & Regionaal Historisch Centrum Limburg, Maastricht. ISBN 905730399X

- Bosman, p. 21

- Bosman, pp. 25-34

- Bosman, pp. 165-166

- Church website. "Geschiedenis". Sterre-der-zee.nl (in Dutch). Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- Bosman, pp. 143-149

- Van Term, p. 9

- Den Hartog, pp. 415-463

- Den Hartog, pp. 270-281, 327

- Den Hartog, pp. 482-488

- Bosman, p. 159

- Koldeweij/Van Vlijmen, pp. 65-66

- De Kreek, pp. 90-115

- De Kreek, pp. 237-246

- De Kreek, pp. 167-174

- De Kreek, pp. 179-181

- De Kreek, pp. 143-148

- De Kreek, pp. 158-164

- De Kreek, pp. 192-195, 205-207

- De Kreek, pp. 132-141

- De Kreek, pp. 230-236