Poznań

Poznań (UK: /ˈpɒznæn/ POZ-nan, US: /ˈpoʊznæn, ˈpoʊznɑːn/ POHZ-nan, POHZ-nahn,[2] Polish: [ˈpɔznaj̃] or [ˈpɔznaɲ] (![]()

Poznań | |

|---|---|

| |

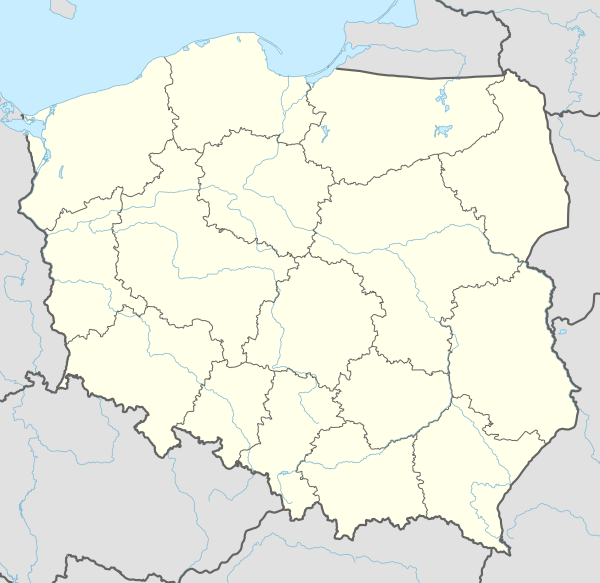

Poznań Location of Poznan in Poland  Poznań Poznań (Poland) | |

| Coordinates: 52°24′N 16°55′E | |

| Country | Poland |

| Voivodeship | Greater Poland Voivodeship |

| County | city county |

| Established | 10th century |

| Town rights | 1253 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jacek Jaśkowiak (PO) |

| Area | |

| • City | 261.85 km2 (101.10 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 154 m (505 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 60 m (200 ft) |

| Population (31 December 2019) | |

| • City | 534,813 |

| • Urban | 1.1 million |

| • Metro | 1.4 million |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 60-001 to 61–890 |

| Area code(s) | +48 61 |

| Vehicle registration | PO, PY |

| Website | www |

Poznań is the fifth-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. The city's population is 538,633 (2011 census), while the continuous conurbation with Poznań County and several other communities is inhabited by almost 1.1 million people.[3] The Larger Poznań Metropolitan Area (PMA) is inhabited by 1.3–1.4 million people and extends to such satellite towns as Nowy Tomyśl, Gniezno and Września,[4][5][6][7] making it the fourth largest metropolitan area in Poland. It is the historical capital of the Greater Poland region and is currently the administrative capital of the province called Greater Poland Voivodeship.

Poznań is a center of trade, sports, education, technology and tourism. It is an important academic site, with about 130,000 students and Adam Mickiewicz University, the third largest Polish university. Poznań is also the seat of the oldest Polish diocese, now being one of the most populous archdioceses in the country. The city also hosts the Poznań International Fair – the biggest industrial fair in Poland and one of the largest fairs in Europe. The city's most renowned landmarks include Poznań Town Hall, the National Museum, Grand Theatre, Fara Church, Poznań Cathedral and the Imperial Castle.

Poznań is classified as a Gamma- global city by Globalization and World Cities Research Network.[8] It has often topped rankings as a city with very high quality of education and a very high standard of living.[9] It also ranks highly in safety and healthcare quality.[10] The city of Poznań has also, many times, won the prize awarded by "Superbrands" for a very high quality city brand. In 2012, the Poznań's Art and Business Center "Stary Browar" won a competition organised by National Geographic Traveler and was given the first prize as one of the seven "New Polish Wonders".

The official patron saints of Poznań are Saint Peter and Paul of Tarsus, the patrons of the cathedral. Martin of Tours – the patron of the main street Święty Marcin is also regarded as one of the patron saints of the city.

Names

The name Poznań probably comes from a personal name, Poznan (from the Polish participle poznan(y) – "one who is known/recognized"), and would mean "Poznan's town". It is also possible that the name comes directly from the verb poznać, which means "to get to know" or "to recognize," so it may simply mean "known town".

The earliest surviving references to the city are found in the chronicles of Thietmar of Merseburg, written between 1012 and 1018: episcopus Posnaniensis ("bishop of Poznań", in an entry for 970) and ab urbe Posnani ("from the city of Poznań", for 1005). The city's name appears in documents in the Latin nominative case as Posnania in 1236 and Poznania in 1247. The phrase in Poznan appears in 1146 and 1244.

The city's full official name is Stołeczne Miasto Poznań ("The Capital City of Poznań"), in reference to its role as a centre of political power in the early Polish state. Poznań is known as Posen in German, and was officially called Haupt- und Residenzstadt Posen ("Capital and Residence City of Poznań") between 20 August 1910 and 28 November 1918. The Latin names of the city are Posnania and Civitas Posnaniensis. Its Yiddish name is פּױזן, or Poyzn.

In Polish, the city name has masculine grammatical gender.

History

For centuries before the Christianization of Poland, Poznań (consisting of a fortified stronghold between the Warta and Cybina rivers, on what is now Ostrów Tumski) was an important cultural and political centre of the Polan tribe. Mieszko I, the first historically recorded ruler of the Polans, and of the early Polish state which they dominated, built one of his main stable headquarters in Poznań. Mieszko's baptism of 966, seen as a defining moment in the Christianization of the Polish state, may have taken place in Poznań.

Following the baptism, construction began of Poznań's cathedral, the first in Poland. Poznań was probably the main seat of the first missionary bishop sent to Poland, Bishop Jordan. The Congress of Gniezno in 1000 led to the country's first permanent archbishopric being established in Gniezno (which is generally regarded as Poland's capital in that period), although Poznań continued to have independent bishops of its own. Poznań's cathedral was the place of burial of the early Piast monarchs (Mieszko I, Boleslaus I, Mieszko II, Casimir I), and later of Przemysł I and King Przemysł II.

The pagan reaction that followed Mieszko II's death (probably in Poznań) in 1034 left the region weak, and in 1038, Duke Bretislaus I of Bohemia sacked and destroyed both Poznań and Gniezno. Poland was reunited under Casimir I the Restorer in 1039, but the capital was moved to Kraków, which had been relatively unaffected by the troubles. In 1138, by the testament of Bolesław III, Poland was divided into separate duchies under the late king's sons, and Poznań and its surroundings became the domain of Mieszko III the Old, the first of the Dukes of Greater Poland. This period of fragmentation lasted until 1320. Duchies frequently changed hands; control of Poznań, Gniezno and Kalisz sometimes lay with a single duke, but at other times these constituted separate duchies.

In about 1249, Duke Przemysł I began constructing what would become the Royal Castle on a hill on the left bank of the Warta. Then in 1253 Przemysł issued a charter to Thomas of Guben (Gubin) for the founding of a town under Magdeburg law, between the castle and the river. Thomas brought a large number of German settlers to aid in the building and settlement of the city – this is an example of the German eastern migration (Ostsiedlung) characteristic of that period.[11][12] The city (covering the area of today's Old Town neighbourhood) was surrounded by a defensive wall, integrated with the castle. According to Walter Kuhn, in 1400 three-quarters of the town's population was German-speaking.[13]

In reunited Poland, and later in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Poznań was the seat of a voivodeship. The city's importance began to grow in the Jagiellonian period, due to its position on trading routes from Lithuania and Ruthenia to western Europe. It would become a major centre for the fur trade by the late 16th century. Suburban settlements developed around the city walls, on the river islands and on the right bank, with some (Ostrów Tumski, Śródka, Chwaliszewo, Ostrówek) obtaining their own town charters. However the city's development was hampered by regular major fires and floods. On 2 May 1536 a fire destroyed 175 buildings, including the castle, the town hall, the monastery and the suburban settlement called St. Martin.[14] In 1519 the Lubrański Academy had been established in Poznań as an institution of higher education (but without the right to award degrees, which was reserved to Kraków's Jagiellonian University). However a Jesuits' college, founded in the city in 1571 during the Counter-Reformation, had the right to award degrees from 1611 until 1773, when it was combined with the Academy.

In the second half of the 17th century and most of the 18th, Poznań was severely affected by a series of wars (and attendant military occupations, lootings and destruction) – the Second and Third Northern Wars, the War of the Polish Succession, the Seven Years' War and the Bar Confederation rebellion. It was also hit by frequent outbreaks of plague, and by floods, particularly that of 1736, which destroyed most of the suburban buildings. The population of the conurbation declined (from 20,000 around 1600 to 6,000 around 1730), and Bambergian and Dutch settlers (Bambrzy and Olędrzy) were brought in to rebuild the devastated suburbs. In 1778 a "Committee of Good Order" (Komisja Dobrego Porządku) was established in the city, which oversaw rebuilding efforts and reorganised the city's administration. However, in 1793, in the Second Partition of Poland, Poznań came under the control of the Kingdom of Prussia, becoming part of (and initially the seat of) the province of South Prussia.

The Prussian authorities expanded the city boundaries, making the walled city and its closest suburbs into a single administrative unit. Left-bank suburbs were incorporated in 1797, and Ostrów Tumski, Chwaliszewo, Śródka, Ostrówek and Łacina (St. Roch) in 1800. The old city walls were taken down in the early 19th century, and major development took place to the west of the old city, with many of the main streets of today's city centre being laid out.

In the Greater Poland uprising of 1806, Polish soldiers and civilian volunteers assisted the efforts of Napoleon by driving out Prussian forces from the region. The city became a part of the Duchy of Warsaw in 1807, and was the seat of Poznań Department – a unit of administrative division and local government. However, in 1815, following the Congress of Vienna, the region was returned to Prussia, and Poznań became the capital of the semi-autonomous Grand Duchy of Posen.

The city continued to expand, and various projects were funded by Polish philanthropists, such as the Raczyński Library and the Bazar hotel. The city's first railway, running to Stargard, opened in 1848. Due to its strategic location, the Prussian authorities intended to make Poznań into a fortress city, building a ring of defensive fortifications around it. Work began on the citadel (Fort Winiary) in 1828, and in subsequent years the entire set of defences (Festung Posen) was completed.

A Greater Poland Uprising during the Revolutions of 1848 was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Grand Duchy lost its remaining autonomy, Poznań becoming simply the capital of the Prussian Province of Posen. It would become part of the German Empire with the unification of German states in 1871. Polish patriots continued to form societies (such as the Central Economic Society for the Grand Duchy of Poznań), and a Polish theatre (Teatr Polski, still functioning) opened in 1875; however the authorities made efforts to Germanize the region, particularly through the Prussian Settlement Commission (founded 1886). Germans accounted for 38% of the city's population in 1867, though this percentage would later decline somewhat, particularly after the region returned to Poland.

Another expansion of Festung Posen was planned, with an outer ring of more widely spaced forts around the perimeter of the city. Building of the first nine forts began in 1876, and nine intermediate forts were built from 1887. The inner ring of fortifications was now considered obsolete and came to be mostly taken down by the early 20th century (although the citadel remained in use). This made space for further civilian construction, particularly the Imperial Palace (Zamek), completed 1910, and other grand buildings around it (including today's central university buildings and the opera house). The city's boundaries were also significantly extended to take in former suburban villages: Piotrowo and Berdychowo in 1896, Łazarz, Górczyn, Jeżyce and Wilda in 1900, and Sołacz in 1907.

At the end of World War I, the final Greater Poland Uprising (1918–1919) brought Poznań and most of the region back to newly reborn Poland, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Versailles. The local German populace had to acquire Polish citizenship or leave the country. This led to a wide emigration of the ethnic Germans of the town's population. The town's German population decreased from 65,321 in 1910 to 5,980 in 1926 and further to 4,387 in 1934.[15] In the interwar Second Polish Republic, the city again became the capital of Poznań Voivodeship. Poznań's university (today called Adam Mickiewicz University) was founded in 1919, and in 1925 the Poznań International Fairs began. In 1929 the fairs site was the venue for a major National Exhibition (Powszechna Wystawa Krajowa, popularly PeWuKa) marking the tenth anniversary of independence; it attracted around 4.5 million visitors. The city's boundaries were again expanded in 1925 (to include Główna, Komandoria, Rataje, Starołęka, Dębiec, Szeląg and Winogrady) and 1933 (Golęcin, Podolany).

During the German occupation of 1939–1945, Poznań was incorporated into the Third Reich as the capital of Reichsgau Wartheland. Many Polish inhabitants were executed, arrested, expelled to the General Government or used as forced labour; at the same time many Germans and Volksdeutsche were settled in the city. The German population increased from around 5,000 in 1939 (some 2% of the inhabitants) to around 95,000 in 1944.[16][17] The pre-war Jewish population of about 2,000[18] were mostly murdered in the Holocaust. A concentration camp was set up in Fort VII, one of the 19th-century perimeter forts. The camp was later moved to Żabikowo south of Poznań. The Nazi authorities significantly expanded Poznań's boundaries to include most of the present-day area of the city; these boundaries were retained after the war. Poznań was captured by the Red Army, assisted by Polish volunteers, on 23 February 1945 following the Battle of Poznań, in which the German army conducted a last-ditch defence in line with Hitler's designation of the city as a Festung. The Citadel was the last point to be taken, and the fighting left much of the city, particularly the Old Town, in ruins, including many monuments (for example Gutzon Borglum's statue of Woodrow Wilson in Poznan.[19]).

Due to the expulsion and flight of German population Poznań's post-war population was almost uniformly Polish. The city again became a voivodeship capital; in 1950 the size of Poznań Voivodeship was reduced, and the city itself was given separate voivodeship status. This status was lost in the 1975 reforms, which also significantly reduced the size of Poznań Voivodeship.

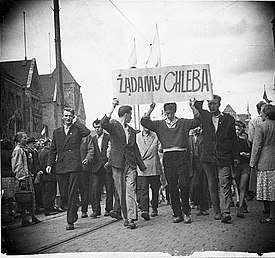

The Poznań 1956 protests are seen as an early instance of discontent with communist rule. In June 1956, a protest by workers at the city's Cegielski locomotive factory developed into a series of strikes and popular protests against the policies of the government. After a protest march on 28 June was fired on, crowds attacked the communist party and secret police headquarters, where they were repulsed by gunfire. Riots continued for two days until being quelled by the army; 67 people were killed according to official figures. A monument to the victims was erected in 1981 at Plac Mickiewicza.[20]

The post-war years had seen much reconstruction work on buildings damaged in the fighting. From the 1960s onwards intensive housing development took place, consisting mainly of pre-fabricated concrete blocks of flats, especially in Rataje and Winogrady, and later (following its incorporation into the city in 1974) Piątkowo. Another infrastructural change (completed in 1968) was the rerouting of the river Warta to follow two straight branches either side of Ostrów Tumski.

The most recent expansion of the city's boundaries took place in 1987, with the addition of new areas mainly to the north, including Morasko, Radojewo and Kiekrz. The first free local elections following the fall of communism took place in 1990. With the Polish local government reforms of 1999, Poznań again became the capital of a larger province (Greater Poland Voivodeship). It also became the seat of a powiat ("Poznań County"), with the city itself gaining separate powiat status.

Recent infrastructural developments include the opening of the fast tram route (Poznański Szybki Tramwaj, popularly Pestka) in 1997, and Poznań's first motorway connection (part of the A2 autostrada) in 2003. In 2006 Poland's first F-16 Fighting Falcons came to be stationed at the 31st Air Base in Krzesiny in the south-east of the city.

Poznań continues to host regular trade fairs and international events, including the United Nations Climate Change Conference in 2008. It was one of the host cities for UEFA Euro 2012.

Geography

Poznań covers an area of 261.3 km2 (100.9 sq mi), and has coordinates in the range 52°17'34''–52°30'27''N, 16°44'08''–17°04'28''E. Its highest point, with an altitude of 157 m (515 ft), is the summit of Góra Moraska (Morasko Hill) within the Morasko meteorite nature reserve in the north of the city. The lowest altitude is 60 m (197 ft), in the Warta valley.

Poznań's main river is the Warta, which flows through the city from south to north. As it approaches the city centre it divides into two branches, flowing west and east of Ostrów Tumski (the cathedral island) and meeting again further north. The smaller Cybina river flows through eastern Poznań to meet the east branch of the Warta (that branch is also called Cybina – its northern section was originally a continuation of that river, while its southern section has been artificially widened to form a main stream of the Warta). Other tributaries of the Warta within Poznań are the Junikowo Stream (Strumień Junikowski), which flows through southern Poznań from the west, meeting the Warta just outside the city boundary in Luboń; the Bogdanka and Wierzbak, formerly two separate tributaries flowing from the north-west and along the north side of the city centre, now with their lower sections diverted underground; the Główna, flowing through the neighbourhood of the same name in north-east Poznań; and the Rose Stream (Strumień Różany) flowing east from Morasko in the north of the city. The course of the Warta in central Poznań was formerly quite different from today: the main stream ran between Grobla and Chwaliszewo, which were originally both islands. The branch west of Grobla (the Zgniła Warta – "rotten Warta") was filled in late in the 19th century, and the former main stream west of Chwaliszewo was diverted and filled in during the 1960s. This was done partly to prevent floods, which did serious damage to Poznań frequently throughout history.

Poznań's largest lake is Jezioro Kierskie (Kiekrz Lake) in the extreme north-west of the city (within the city boundaries since 1987). Other large lakes include Malta (an artificial lake on the lower Cybina, formed in 1952), Jezioro Strzeszyńskie (Strzeszyn Lake) on the Bogdanka, and Rusałka, an artificial lake further down the Bogdanka, formed in 1943. The latter two are popular bathing places. Kiekrz Lake is much used for sailing, while Malta is a competitive rowing and canoeing venue.

The city centre (including the Old Town, the former islands of Grobla and Chwaliszewo, the main street Święty Marcin and many other important buildings and districts) lies on the west side of the Warta. Opposite it between the two branches of the Warta is Ostrów Tumski, containing Poznań Cathedral and other ecclesiastical buildings, as well as housing and industrial facilities. Facing the cathedral on the east bank of the river is the historic district of Śródka. Large areas of apartment blocks, built from the 1960s onwards, include Rataje in the east, and Winogrady and Piątkowo north of the centre. Older residential and commercial districts include those of Wilda, Łazarz and Górczyn to the south, and Jeżyce to the west. There are also significant areas of forest within the city boundaries, particularly in the east adjoining Swarzędz, and around the lakes in the north-west.

For more details on Poznań's geography, see the articles on the five districts: Stare Miasto, Nowe Miasto, Jeżyce, Grunwald and Wilda.

Climate

The climate of Poznań is within the transition zone between a humid continental and oceanic climate (Köppen: Cfb to Dfb although it totally fits in the second in the 0 °C isotherm) and with relatively cold winters and warm summers. Snow is common in winter, when night-time temperatures are typically below zero. In summer temperatures may often reach 30 °C (86 °F). Annual rainfall is more than 500 mm (20 in), among the lowest in Poland. The rainiest month is July, mainly due to short but intense cloudbursts and thunderstorms. The number of hours of sunshine are among the highest in the country. Climate in this area has mild differences between highs and lows, and there is adequate rainfall year-round. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "humid continental climate).[21]

| Climate data for Poznań (Poznań Airport), elevation: 83 m or 272 ft, 1981–2010 normals | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

21.5 (70.7) |

29.3 (84.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

36.8 (98.2) |

38.7 (101.7) |

37.0 (98.6) |

30.4 (86.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.9 (57.0) |

38.7 (101.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 2.3 (36.1) |

2.9 (37.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.5 (76.1) |

19.3 (66.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.2 (37.8) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

4.0 (39.2) |

9.8 (49.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.1 (68.2) |

19.8 (67.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.9 (49.8) |

4.4 (39.9) |

0.2 (32.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.6 (23.7) |

−4.3 (24.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

6.0 (42.8) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.1 (59.2) |

11.3 (52.3) |

5.9 (42.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

−2.8 (27.0) |

5.7 (42.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.5 (−19.3) |

−24.0 (−11.2) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−1.5 (29.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.9 (39.0) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−13.6 (7.5) |

−19.2 (−2.6) |

−28.5 (−19.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 33 (1.3) |

27 (1.1) |

38 (1.5) |

31 (1.2) |

50 (2.0) |

57 (2.2) |

76 (3.0) |

61 (2.4) |

42 (1.7) |

34 (1.3) |

35 (1.4) |

40 (1.6) |

524 (20.6) |

| Average precipitation days | 14 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 13 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 142 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 82 | 75 | 68 | 63 | 68 | 70 | 72 | 74 | 77 | 80 | 82 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 56 | 67 | 118 | 179 | 230 | 237 | 236 | 229 | 171 | 122 | 55 | 40 | 1,740 |

| Source: Polish Central Statistical Office | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Poznań (Poznań Airport), elevation: 83 m or 272 ft, 1961–1990 normals and extremes | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.2 (55.8) |

17.6 (63.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

29.9 (85.8) |

31.5 (88.7) |

33.7 (92.7) |

36.4 (97.5) |

36.1 (97.0) |

34.6 (94.3) |

27.9 (82.2) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.0 (59.0) |

36.4 (97.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.5 (32.9) |

2.2 (36.0) |

6.8 (44.2) |

13.0 (55.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.1 (55.6) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.2 (36.0) |

12.5 (54.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−1.0 (30.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

7.6 (45.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

17.4 (63.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

8.8 (47.8) |

3.8 (38.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4.8 (23.4) |

−3.9 (25.0) |

−0.8 (30.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

7.7 (45.9) |

11.2 (52.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

12.2 (54.0) |

9.0 (48.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

4.1 (39.5) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −28.5 (−19.3) |

−26.7 (−16.1) |

−21.4 (−6.5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−3.0 (26.6) |

0.5 (32.9) |

4.7 (40.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−24.9 (−12.8) |

−28.5 (−19.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30 (1.2) |

24 (0.9) |

27 (1.1) |

36 (1.4) |

53 (2.1) |

60 (2.4) |

69 (2.7) |

57 (2.2) |

43 (1.7) |

39 (1.5) |

39 (1.5) |

38 (1.5) |

515 (20.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 8.1 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 7.3 | 8.4 | 8.7 | 9.2 | 9.0 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 96.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 40.0 | 61.0 | 109.0 | 152.0 | 219.0 | 215.0 | 218.0 | 206.0 | 138.0 | 102.0 | 40.0 | 32.0 | 1,532 |

| Source: NOAA[22] | |||||||||||||

Administrative division

Poznań is divided into 42 neighbourhoods (see osiedle), each of which has its own elected council with certain decision-making and spending powers. The first uniform elections for these councils covering the whole area of the city were held on 20 March 2011.

For certain administrative purposes, the old division into five districts (dzielnicas) is used – although these ceased to be governmental units in 1990. These were:

- Stare Miasto ("Old Town"), population 161,200, area 47.1 km2 (18.2 sq mi), covering the central and northern parts of the city

- Nowe Miasto ("New Town"), population 141,424, area 105.1 km2 (40.6 sq mi), including all parts of the city on the right (east) bank of the Warta

- Grunwald, population 125,500, area 36.2 km2 (14.0 sq mi), covering the south-western parts of the city

- Jeżyce, population 81,300, area 57.9 km2 (22.4 sq mi), covering the north-western parts of the city

- Wilda, population 62,290, area 15.0 km2 (5.8 sq mi), in the southern part of the city

Many citizens of Poznań thanks to the strong economy of the city and high salaries started moving to suburbs of the Poznań County (powiat) in the 1990s. Although the number of inhabitants in Poznań itself was decreasing for the past two decades, the suburbs gained almost twice as many inhabitants. Thus, Poznań urban area has been growing steadily over past years and has already reached 1.0 million inhabitants when student population is included, whereas the entire metropolitan zone may have reached 1.5–1.7 million inhabitants when satellite cities and towns (so-called second Poznań ring counties such as Września, Gniezno and Kościan) are included. The complex infrastructure, population density, number of companies and gross product per capita of Poznań suburbs may be only compared to Warsaw suburbs. Many parts of closer suburbs (for example Tarnowo Podgorne, Komorniki, Suchy Las, Dopiewo) produce more in terms of GDP per capita than the city itself.

Economy

Poznań has been an important trade centre since the Middle Ages. Starting in the 19th century, local heavy industry began to grow. Several major factories were built, including the Hipolit Cegielski steel mill and railway factory (see H. Cegielski - Poznań S.A.).

Nowadays Poznań is one of the major trade centres in Poland. Poznań is regarded as the second most prosperous city in Poland after Warsaw. The city of Poznań produced PLN 31.8 billion of Poland's gross domestic product in 2006. It boasts a GDP per capita of 200.4% (2008) of Poland's average. Furthermore, Poznań had very low unemployment rate of 2.3% as of May 2009. For comparison, Poland's national unemployment rate was over 10%.

Many Western European companies have established their Polish headquarters in Poznań or in the nearby towns of Tarnowo Podgórne and Swarzędz. Most foreign investors are German and Dutch companies, with a few others. The best known examples of corporation who have their headquarters in Poznań and the surrounding areas are that of GlaxoSmithKline, Raben Group (near Kórnik) and Kuehne + Nagel (near Gądki).

Investors are mostly from the food processing, furniture, automotive and transport and logistics industries. Foreign companies are primarily attracted by low labour costs and by the relatively good road and railway network, good vocational skills of workers and relatively liberal employment laws.

The recently built Stary Browar shopping centre contains many high-end shops and is considered one of the best in Europe. It has won an award for the best shopping centre in the world in the medium-sized commercial buildings category. Other notable shopping centres in the city include Galeria Malta, one of the largest in Central Europe, and the shops at the Hotel Bazar, a historical hotel and commercial centre in the Old Town.

Some of the best-known major corporations founded and still based in Poznań and the city's metropolitan area include Allegro, Poland's biggest online auction site, H. Cegielski-Poznań SA, a historic manufacturer, Solaris Bus & Coach, a modern bus and coach maker based in Bolechowo and Enea S.A., one of the country's biggest energy firms. Poznań is also where the software development leader Netguru was founded, one of the fastest growing companies in Europe. Kompania Piwowarska based in Poznań produces some of Poland's best known beers, and includes not only the local Lech Brewery but also Tyskie from Tychy and Dojlidy Brewery from Białystok among many others.

Transport

Poznań has an extensive public transport system, mostly consisting of trams, such as the Poznań Fast Tram, and both urban and suburban buses. The main railway station is Poznań Central Station to the southwest of the city centre; there is also the smaller Poznań Wschód and Poznań Garbary station northeast of the centre and a number of other stations on the outskirts of the city. The main east-west A2 motorway runs south of the city connecting it with Berlin in the west and Łódż and Warsaw in the east; other main roads run in the direction of Warsaw, Bydgoszcz, Wągrowiec, Oborniki, Katowice, Wrocław, Buk and Berlin. Poznań has one of the biggest airports in the west of Poland called Poznań-Ławica Airport. In 2016 it handled approximately 1.71 million passengers.

- A2 Motorway in Poznań

- Solaris Urbino Bus

Poznań Central Station

Poznań Central Station

Culture and sights

Poznań has many historic buildings and sights, mostly concentrated around the Old Town and other parts of the city centre. Many of these lie on the Royal-Imperial Route in Poznań – a tourist walk leading through the most important parts of the city showing its history, culture and identity. Portions of the city centre are listed as one of Poland's official national Historic Monuments (Pomnik historii), as designated 28 November 2008, along with other portions of the city's historic core. Its listing is maintained by the National Heritage Board of Poland.

Results of new extensive archaeological research performed on Poznań's Ostrów Tumski by Prof. dr hab. Hanna Kocka-Krec from Instytut Prahistorii UAM indicate that Poznań indeed was a central site of the early Polish State (recent discovery of first Polish ruler, Mieszko I's Palatium). Thus, the Tumski Island is more important than it was thought previously, and may have been as important as Gniezno in the Poland of first Piasts. Though it is currently under construction, Ostrów Tumski of Poznań should soon have a very rich historical exposition and be a very interesting place for visitors. It promises to include many attractions, such as the above-mentioned Cathedral, Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Lubranski Academy and they opened in 2012 Genius Loci Archeological Park as well as planned to be opened in 2013 Interactive Center of Ostrów Tumski History (ICHOT) that presents a multimedia museum of the Polish State through many different periods. The Palatium in Poznań will be also transformed into a museum, although more funds are needed. When all the expositions are ready, in a couple of years, Ostrów Tumski may be as worth visiting as the Wawel Castle of Kraków. There is a very famous sentence illustrating the importance of Ostrów Tumski in Poznań by the Pope John Paul II: "Poland began here".

A popular venue is Malta, a park with an artificial lake in its centre. On one bank of the lake there are ski and sleigh slopes (Malta Ski), on the opposite bank a huge complex of swimming pools including an Olympic-size one (Termy Maltanskie).

An important cultural event in Poznań is the annual Malta Festival, which takes place at many city venues, usually in late June and early July. It hosts mainly modern experimental off-theatre performances, often taking place on squares and other public spaces. It also includes cinema, visual, music and dancing events. Malta Theatre Festival gave birth to many off-theater groups, expressing new ideas in an already rich theatrical background of the city. Thus, Poznań with a great deal of off-theaters and their performances has recently become a new Polish off-theater performance centre.

.jpg)

Classical music events include the Henryk Wieniawski Violin Competition (held every 5 years), and classical music concerts by the city's Philharmonic Orchestra held each month in the University Aula. Especially popular are concerts by the Poznań Nightingales.

Poznań is also home to new forms of music such as rap and hip-hop made by a great deal of bands and performers ("Peja", "Mezo" and others). Poznań is also known for its rock music performers (Muchy, Malgorzata Ostrowska).

Poznań apart from many traditional theatres with a long history ("Teatr Nowy", "Teatr Wielki", "Teatr Polski", "Teatr Muzyczny" and several others) is also home to a growing number of alternative theatre groups, some of them stemming from International Malta Festival: "Teatr Strefa Ciszy", "Teatr Porywcze Cial", "Teatr Usta Usta", "Teatr u Przyjaciol", "Teatr Biuro Podrozy", "Teatr Osmego Dnia" and many others – it is believed that even up to 30 more or less known groups may work in the city.

Every year on 11 November, Poznanians celebrate The Day of St. Martin. A procession of horses, with St. Martin at the head, parades along St Martin Street, in front of The Imperial Castle. Everybody can eat delicious croissants, the regional product of Poznań.

Poznań hosted the 2009 European Young Adults Meeting of the ecumenical Christian Taizé Community.

Poznań also stages the Ale Kino! International Young Audience Film Festival in December and "Off Cinema" festival of independent films. Other festivals: "Transatlantyk (film music festival by Jan A.P. Kaczmarek started in 2011), Maski Theater Festival, Dance International Workshops by Polish Dance Theater, Made in Chicago (Jazz Festival), Ethno Port, Festival of Ice Sculpture, animator, Science and Art Festival, Tzadik (Jewish music festival), Meditations Biennale (Modern Art).

Poznań has several cinemas, including multiplexes and smaller cinemas, an opera house, several other theatres, and museums. The Rozbrat social centre, a squatted former factory in Jeżyce, serves as a home for independent and open-minded culture. It hosts frequent gigs, an anarchistic library, vernissages, exhibitions, annual birthday festival (each October), poetry evenings and graffiti festivals. The city centre has many clubs, pubs and coffee houses, mainly in the area of the Old Town.

The city is also home to one of the oldest zoological gardens in Poland, the Old Zoo in Poznań, which was established in 1874.[23]

Grażyna Kulczyk's effort to build the Museum of Contemporary and Performance Arts in Poznań was rejected.[24][25]

A Chip Shop in Poznan: My Unlikely Year in Poland is a travel book published in 2019, which details British author Ben Aitken's experience of being an immigrant in the city. Aitken worked in a fish and chip shop, travelling the country between shifts.

Education

Poznań is one of the four largest academic centres in Poland. The number of students in the city of Poznań is about 140,000 (fourth/third after Warsaw, Kraków and close to Wrocław student population). Every one of four inhabitants in Poznań is a student.

Since Poznań is smaller than Warsaw or Kraków still having a very large number of students it makes the city even more vibrant and dense academic hub than both former and current capitals of Poland. Poznań, with its almost 30 colleges and universities, has the second richest educational offering in Poland after Warsaw.

Public universities

The city has many state-owned universities. Adam Mickiewicz University (abbreviated UAM in Polish, AMU in English) is one of the most influential and biggest universities in Poland:

- Adam Mickiewicz University (UAM)

- University of Fine Arts in Poznań

- Academy of Music in Poznań

- Poznań University of Economics

- Poznań University of Medical Sciences

- Poznań University of Technology

- Poznań University School of Physical Education

- University of Life Sciences in Poznań

Adam Mickiewicz University is one of the three best universities in Poland after University of Warsaw and University of Kraków. They all have a very high number of international student and scientist exchange, research grants and top publications. In northern suburbs of Poznań a very large "Morasko Campus" has been built (Faculty of Biology, Physics, Mathematics, Chemistry, Political Sciences, Geography). The majority of faculties are already open, although a few more facilities will be constructed. The campus infrastructure belongs to the most impressive among Polish universities. Also, there are plans for "Uniwersytecki Park Historii Ziemii" (Earth History Park), one of the reason for the park construction is a "Morasko meteorite nature reserve" situated close by, it is one of the rare sites of Europe where a number of meteorites fell and some traces may be still seen.

Private higher education

There is also a great number of smaller, mostly private-run colleges and institutions of higher education ("Uczelnie"):

- University of Social Sciences and Humanities

- Collegium Da Vinci

- Poznańska Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu i Języków Obcych

- Schola Posnaniensis – Wyższa Szkoła Sztuki Stosowanej

- Wielkopolska Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki i Zarządzania

- Wyższa Szkoła Bankowa w Poznaniu[26]

- Branch in Chorzów

- Wyższa Szkoła Handlu i Usług

- Wyższa Szkoła Umiejętności Społecznych

- Branch in Katowice

- Wyższa Szkoła Zarządzania i Bankowości

- Wrocław branch

- École Franco-Polonaise – closed in 1997

- Arcybiskupie Seminarium Duchowne w Poznaniu

- Wielkopolska Wyższa Szkoła Turystyki i Zarządzania w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Biznesu

- Wyższa Szkoła Bezpieczeństwa w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Edukacji i Terapii w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Edukacji Integracyjnej i Interkulturowej w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Handlu i Rachunkowości

- Branch in Września

- Wyższa Szkoła Hotelarstwa i Gastronomii

- Wyższa Szkoła Języków Obcych im. Samuela Bogumiła Lindego

- Wyższa Szkoła Komunikacji i Zarządzania w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Logistyki

- Wyższa Szkoła Pedagogiki i Administracji im. Mieszka I w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa "Kadry dla Europy" w Poznaniu

- Wyższa Szkoła Zawodowa Pielęgnacji Zdrowia i Urody

- Wyższe Seminarium Duchowne Towarzystwa Chrystusowego

High schools

Poznań has numerous high schools, each with a different programme focusing on different subjects. Some of the most notable are:

Scientific and regional organisations

- Poznań Society of Friends of Arts and Sciences

- Poznań Supercomputing and Networking Center

- Western Institute

Sports

Poznań is famous for its football teams, Warta Poznań, which was one of the most successful clubs in pre-war history, and Lech Poznań, who are currently one of the biggest clubs in the country, frequently playing in European cups and have many fans from all over the region. Lech plays at the Municipal Stadium, which hosted the 2012 European Championship group stages as well as the opening game and the final of the U-19 Euro Championship in June 2006. Warta usually plays at the small Dębińska Road Stadium; a former training ground for Edmund Szyc Stadium however since the latter fell into disrepair in 1998 and was sold in 2001 it became the team's main ground; the club does have aims to restore and return to the historical 60 000 capacity stadium.[27] However in 2019/2020 season in the I liga Warta is playing their matches on Stadium in Grodzisk Wielkopolski, as their original stadium didn't fulfill the requirements of the I liga's authorities.[28]

The city's third professional football team Olimpia Poznań ceased activity in 2004, focusing on other sports, and remains one of the best judo and tennis clubs in the country, the latter hosting the Poznań Open tournament at the Tennis Park. The club is a large sports complex surrounded by Lake Rusałka, and apart from the tennis facilities boasts a large city recreation area: mountain biking facilities including a four-cross track; an athletics stadium (capacity 3000); and a football-speedway stadium (capacity 20 000), which fell into vast disrepair until it was acquired by the city council from the police in 2013 and was renovated. The football-speedway stadium hosts speedway club PSŻ Poznań, rugby union side NKR Chaos, American football team the Armia Poznań[29], and football team Poznaniak Poznań.

The city has the largest circuit in Poland, Tor Poznań, located in the suburbs in Przeźmierowo. Lake Malta hosted the World Rowing Championships in 2009 and has previously hosted some regattas in the Rowing World Cup. It also hosted the ICF Canoe Sprint World Championships (sprint canoe) in 1990 and 2001, and again in 2010. Also near the lake the "Malta Ski" year-long skiing complex hosts minor sport competitions, and is also equipped with a toboggan run and a minigolf course. There is also a roller rink with a roller skating club nearby.

Poznań has experience as a host for international sporting events such as the official 2009 EuroBasket.[30]

The city is also considered to be the hotbed of Polish field hockey, with several top teams: Warta Poznań; Grunwald Poznań; which also has shooting, wrestling, handball and tennis sections; Pocztowiec Poznań; and AZS AWF Poznań, the student club which also fields professional teams in women's volleyball and basketball (AZS Poznań).

Other clubs include: Posnania Poznań, one of the best rugby union clubs in the country; Polonia Poznań, formerly a multi-sports club with many successes in rugby, however today only a football section remains; KKS Wiara Lecha, football club formed by the supporters of Lech Poznań; and Odlew Poznań, arguably the most famous amateur club in the country due to their extensive media coverage and humorous exploits. There are also numerous rhythmic gymnastics and synchronised swimming clubs, as well as numerous less notable amateur football teams.

Poznań bid for the 2014 Summer Youth Olympics but lost to Nanjing, with the Chinese city receiving 47 votes over Poznań's 42.

Infrastructure

Since the end of the communist era in 1989, Poznań municipality and suburban area have invested heavily in infrastructure, especially public transport and administration. There is massive investment from foreign companies in Poznań as well as in communities west and south of Poznań (namely, Kórnik and Tarnowo Podgórne).

City investments into transportation were mostly into public transport. While the number of cars since 1989 has at least doubled, municipal policy concentrated on improving public transport. Limiting car access to the city centre, building new tram lines (including Poznański Szybki Tramwaj) and investing in new rolling stock (such as modern Combino trams by Siemens and Solaris low-floor buses) actually increased the level of ridership.

Future investments into transportation include the construction of a third bypass of Poznań, and the completion of A2 (E30) motorway towards Berlin. New cycle lanes are being built, linking to existing ones, and an attempt is currently being made to develop a Karlsruhe-style light rail system for commuters. All this is made more complicated (and more expensive) by the heavy neglect of transport infrastructure throughout the Communist era.

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Poznań is twinned with:[31][32]

Gallery

Bamberka Fountain

Bamberka Fountain Proserpine Fountain

Proserpine Fountain

.jpg)

- The apse of St. Florian's Church

Poznań University Library

Poznań University Library.jpg) Liberty Square Fountain

Liberty Square Fountain- Spring of Nations Square

- Collegium Maius

Hygieia Statue

Hygieia Statue Bałtyk office building

Bałtyk office building- Okrąglak Department Store

Saint Francis Church

Saint Francis Church Academy of Music

Academy of Music Collegium Chemicum Novum

Collegium Chemicum Novum._Ysbail.jpg) Bank headquarters

Bank headquarters- Termy Maltańskie

- Western Institute

- Underground tram station Piaśnicka/Kurlandzka

Wilson's Park

Wilson's Park

Notable people

- Anna Anderson (c. 1900–1984), pretender of Grand Duchess Anastasia of Russia

- Ryszard "Peja" Andrzejewski (born 1976), rapper

- Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière (1886–1941), German U-boat commander

- Isidor Ascheim (1891–1968), painter and printmaker

- Stanisław Barańczak (1946–2014), poet

- Hanna Banaszak (born 1957), singer, poet

- Herbert Baum (1912–1942) resistance fighter

- Zygmunt Bauman (1925–2017), sociologist

- Heinrich Caro (1834–1910), chemist

- Hipolit Cegielski (1815–1868), businessman

- Dezydery Chłapowski (1788–1848), general

- August Cieszkowski (1814–1894), philosopher

- Antoni Czubiński (1928–2003), historian

- Leopold Damrosch (1832–1885), conductor

- Ludwig Dessoir, (1810–1874), actor

- Franciszek Dobrowolski (1830–1896), theater director

- Tytus Działyński (1796–1861), political activist

- Małgorzata Dydek (1974–2011), basketball player

- Akiva Eiger (1761–1837), Rabbi of Poznań (1815–1837)

- Ewaryst Estkowski (1820–1856), teacher

- Gerard Ettinger (1909–2002), designer and manufacturer of leather goods[47]

- Krystyna Feldman (1916–2007), actress

- Wojciech Fibak (born 1952), tennis player

- Gerhard Flesch (1909–1948), German Nazi Gestapo and SS officer executed for war crimes

- Fredrak Fraske (1872–1973), the last surviving United States veteran of the Indian Wars

- Johannes Gad (1842–1926), neurophysiologist

- Jean Gebser (1905–1973), human consciousness scientist

- Eduard Gerhard (1795–1867), archaeologist

- Arkadiusz Głowacki (born 1979), footballer

- Friedrich Goltz (1834–1902), physiologist

- Konstanty Gorski (1859–1924), composer and violinist

- Joanna Hoffmann-Dietrich (born 1968), artist and academic

- Paul von Hindenburg (1847–1934), Field Marshal and President of the Weimar Republic

- Maksymilian Jackowski (1815–1905), activist

- Anna Jantar (1950–1980), a popular Polish singer, who perished in a plane crash.

- Alfred Jodl (1890–1946), German WW2 military commander executed for war crimes

- John Jonston (1603–1675), naturalist and physician

- Jan A.P. Kaczmarek (born 1954), composer

- Maria and Bogdan Kalinowski, filmgoing couple

- Richard Kandt (1867–1918), doctor and explorer

- Ernst Hartwig Kantorowicz (1895–1963), historian

- Marek Karpinski, computer scientist

- Günther von Kluge (1882–1944), Field Marshal

- Krzysztof Komeda (1931–1969), jazz musician

- Leo Königsberger (1837–1921), mathematician

- Antoni Kraszewski (1797–1870), politician

- Germaine Krull (1897–1985), photographer

- Jakub Kucner (born 1988), male model

- Gerard Labuda (born 1916), historian

- Arthur Liebehenschel (1901–1948), Nazi commandant of Auschwitz and Majdanek executed for war crimes

- Jarosław Leitgeber (1848–1933), purveyor of Polish books under partitions

- Paul Leonhardt (1877–1934), chess master

- Karol Libelt (1807–1875), philosopher

- Karol Marcinkowski (1800–1848), physician and social activist

- Władysław Markiewicz (born 1920), sociologist

- Teofil Matecki (1810–1886), philosopher

- Heinrich Mendelssohn (1881–1959), building tycoon

- Karl-Friedrich Merten (1905–1993), U-boat commander

- Małgorzata Musierowicz (born 1945), novelist

- Andrzej Niegolewski (1787–1857), colonel

- Władysław Niegolewski (1814–1880), politician

- Władysław Oleszczyński (1809–1866), sculptor

- Catherine Opalińska (1680–1747), Queen consort of Poland, Grand Duchess consort of Lithuania

- Lilli Palmer (1914–1986), actress

- Janusz Pałubicki (born 1948), politician

- Kazimierz Piwarski, (1903–1968), historian

- Gustaw Potworowski, (1800–1860), activist

- Edward Raczyński (1786–1845), politician

- Cyryl Ratajski (1875–1942), mayor of Poznań

- Antoni Radziwiłł (1775–1833), aristocrat

- Marian Rejewski (1905–1980), cryptoanalist, Enigma codemachine codebreaker

- Richard Rothe (1799–1867), Lutheran theologian

- Jerzy Różycki (1909–1942), cryptoanalist, Enigma codemachine codebreaker

- Dame Elisabeth Schwarzkopf (1915–2006), operatic and concert lyric soprano, born in Jarocin

- Michał Sczaniecki (1910–1977), historian

- Urszula Sipinska (born 1947), singer-songwriter, pianist and architect

- Bohdan Smoleń (born 9 June 1947), comedian and actor

- Józef Struś (1510–1568), scientist and mayor of Poznań

- Sir Paweł Edmund Strzelecki (20 July 1797 – 6 October 1873), Polish explorer and geologist

- Rafał Szukała (born 1971), butterfly swimmer

- Roman Szymański (1840–1908), political activist

- Mirosław Szymkowiak (born 1976) football player

- Jerzy Topolski (1928–1998), historian

- Lech Trzeciakowski (1931–2017), historian

- Jorge Veytia (born 1981), jurist

- Hubert Wagner (1941–2002), volleyball player and head coach of Poland men's national volleyball team

- Jan Węglarz (born 1947), computer scientist

- Leon Wegner (1824–1873), economist

- Roman Wilhelmi (1936–1991), actor

- Ray Wilson (born 1968), former vocalist of Genesis

- Tommy Wiseau (born 1955), director, script writer, movie maker, and actor, speculated to be born here

- Zygmunt Wojciechowski, (1900–1955), historian and founder of the Western Institute

- Anna Wolff-Powęska, historian

- Henryk Zygalski (1906–1978), cryptoanalist, Enigma codemachine codebreaker

- Judah Loew ben Bezalel (1512 or 1526–1609), important Talmudic scholar, Jewish mystic, and philosopher

See also

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Posen (city). |

- Tourism in Poland

- History of Poland

- Royal coronations in Poland including in Poznań cathedral

- Poznań Fortress

- The Poznań

- 15th Poznań Uhlans Regiment

References

- "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 21 June 2020. Data for territorial unit 3064000.

- "Poznan". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- "Liczba ludności aglomeracji poznańskiej wzrasta :: Aktualności :: Portal Metropolii Poznań". Aglomeracja.poznan.pl. 21 July 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "RZĄDOWE CENTRUM STUDIÓW STRATEGICZNYCH" (PDF). Funduszestrukturalne.gov.pl. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Wielkopolskie Biuro Planowania Przestrzennego – POZNAŃSKI OBSZAR METROPOLITALNY". Wbpp.poznan.pl. 29 April 2008. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Delimitacja Poznańskiego Obszaru Metropolitalnego". Wbpp.poznan.pl. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Delimitacja Poznańskiego Obszaru Metropolitalnego. Od pomysłu do planu | Derc | Acta Universitatis Nicolai Copernici Ekonomia". Wydawnictwoumk.pl. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "The World According to GaWC 2018". Retrieved 25 December 2018.

- "High quality of life – Study – Poznan.pl". Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- "Quality of Life in Poznan". Retrieved 25 April 2017.

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 87, 156, 159. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. p. 87. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

Das städtische Bürgertum war auch in Polen und Böhmen zunächst überwiegend deutscher Herkunft. [English: Also in Poland and Bohemia were the burghers in the towns initially primarily of German origin.]

- Walter Kuhn. Geschichte der deutschen Ostsiedlung in der Neuzeit (in German). 1. p. 105.

- J. Perles: Geschichte der Juden in Posen. In: Monatsschrift für Geschichte und Wissenschaft des Judentums. Vol. 13, Breslau 1864, pp. 321–334 (in German, online)

- Kotowski, Albert S. (1998). Polens Politik gegenüber seiner deutschen Minderheit 1919–1939 (in German). Forschungsstelle Ostmitteleuropa, University of Dortmund. p. 56. ISBN 3-447-03997-3.

- Jerzy Topolski. Dzieje Poznania w latach 1793–1945: 1918–1945. PWN. 1998. pp. 958, 1425.

- "Trial of Gauleiter Arthur Greiser". Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals. United Nations War Crimes Commission. Wm. S. Hein Publishing. 1997. p. 86.

- "Survival artist: a memoir of the Holocaust", Eugene Bergman, 2009, pg. 20

- Price, Waldine, Gutzon Borglum: The Man Who Carved a Mountain, Waldine Price, 1961 p. 181

- "Monument to the Victims of June 1956". Lonely Planet. 28 June 1981. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Poznan, Poland Köppen Climate Classification". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Poznań (12330) – WMO Weather Station". NOAA. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Welcome to Poznań ZOO". Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- Adam, Georgina (7 March 2014). "Grazyna Kulczyk's collection on show at Boadilla del Monte, Madrid". Financial Times. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- Berendt, Joanna (30 November 2015). "Polish Philanthropist, Grazyna Kulczyk, Is Seeking to Open Museum in Warsaw". New York Times. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- WSB University in Poznań Archived 1 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – WSB Universities

- Polska, Grupa Wirtualna. "Widok jak z horroru w samym centrum miasta. Stadion, który straszy od lat – Magazyn WP". Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- "Warta Poznań będzie grać w Grodzisku Wielkopolskim". sport.interia.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- "Armia Poznań – LFA – Liga Futbolu Amerykańskiego" (in Polish). Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- 2009 EuroBasket, ARCHIVE.FIBA.com, Retrieved 5 June 2016.

- "Poznań – Miasta partnerskie". 1998–2013 Urząd Miasta Poznania (in Polish). City of Poznań. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2013.

- "Poznań Official Website – Twin Towns". (in Polish) [[copyright|]] 1998–2008 Urząd Miasta Poznania. Retrieved 29 November 2008.

- "City of Brno Foreign Relations – Statutory city of Brno" (in Czech). Brno.cz. Archived from the original on 15 January 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2011.

- "Brno – Partnerská města" (in Czech). Brno.cz. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- "Wprowadzenie". Poznan.pl. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "Hanover – Twin Towns" (in German). Hannover.de. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 17 July 2009.

- Archived 14 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- 第五章 友好城市 [Sister Cities]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen Municipal People's Government (in Chinese). 22 March 2008. Archived from the original on 19 July 2014.

- 国际友好城市一览表 [International Sister Cities List]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen Municipal People's Government (in Chinese). 20 January 2011. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013.

- 友好交流 [Friendly exchanges]. Foreign Affairs Office of Shenzhen Municipal People's Government (in Chinese). 2014. Archived from the original on 12 November 2014.

- "The Interior" (PDF). Svsu.edu. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- "The New Old World: Buffalo's Polish Sister City Is Rewriting Its Destiny". Buffalo-Rzeszow Sister Cities, Inc. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014.

- pt:São José dos Pinhais

- http://www.sjp.pr.gov.br/noticias/exposicao-de-litogravura-simboliza-aproximacao-de-sjp-com-cidades-irmas%5B%5D

- http://www.sjp.pr.gov.br/abertura-de-exposicao-sobre-a-imigracao-polonesa-marca-325-anos-da-cidade/%5B%5D

- pt:Posnânia

- "Gerard Ettinger". The Daily Telegraph. 12 August 2002. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

Bibliography

- Frieder Monzer: Posen, Thorn, Bromberg (mit Großpolen, Kujawien und Südostpommern), Trescher Reiseführer, Berlin 2011

- Gotthold Rhode: Geschichte der Stadt Posen, Neuendettelsau 1953

- Collective work, Poznań. Dzieje, ludzie kultura, Poznań 1953

- Robert Alvis, Religion and the Rise of Nationalism: A Profile of an East-Central European City, Syracuse University Press, Syracuse 2005

- K. Malinowski (red.), Dziesięć wieków Poznania (in three volumes), Poznań 1956

- Collective work, Poznań, Poznań 1958

- Collective work, Poznań. Zarys historii, Poznań 1963

- Cz. Łuczak, Życie społeczno-gospodarcze w Poznaniu 1815–1918, Poznań 1965

- J. Topolski (red.), Poznań. Zarys dziejów, Poznań 1973

- Zygmunt Boras, Książęta Piastowscy Wielkopolski, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie, Poznań 1983

- Jerzy Topolski (red.), Dzieje Poznania, Wydawnictwo PWN, Warszawa, Poznań 1988

- Alfred Kaniecki, Dzieje miasta wodą pisane, Wydawnictwo Aquarius, Poznań 1993

- Witold Maisel (red.), Przywileje miasta Poznania XIII-XVIII wieku. Privilegia civitatis Posnaniensis saeculorum XIII-XVIII. Władze Miasta Poznania, Poznańskie Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Nauk, Wydawnictwa Żródłowe Komisji Historycznej, Tom XXIV, Wydawnictwo PTPN, Poznań 1994

- Wojciech Stankowski, Wielkopolska, Wydawnictwo WSiP, Warszawa 1999

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Poznań. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Poznań. |

| Look up Poznań in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |