Bolesław I the Brave

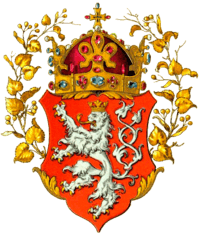

Bolesław the Brave (Polish: Bolesław Chrobry ![]()

| Bolesław I the Brave | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Poland | |

| Reign | 992 – 1025 |

| Predecessor | Mieszko I |

| King of Poland | |

| Reign | 1025 |

| Successor | Mieszko II Lambert |

| Born | 967 Poznań |

| Died | 17 June 1025 (aged 57–58) Kraków? |

| Burial | Cathedral Basilica of Sts. Peter and Paul, Poznań |

| Wives |

|

| Issue Detail | Bezprym Regelinda Mieszko II Lambert Otto |

| Dynasty | Piast |

| Father | Mieszko I of Poland |

| Mother | Dobrawa of Bohemia |

| Religion | Chalcedonian Christianity |

Bolesław supported the missionary goals of Bishop Adalbert of Prague and Bruno of Querfurt. The martyrdom of Adalbert in 997 and his imminent canonization were used to consolidate Poland's autonomy from the Holy Roman Empire. This perhaps happened most clearly during the Congress of Gniezno (11 March 1000), which resulted in the establishment of a Polish church structure with a Metropolitan See at Gniezno. This See was independent of the German Archbishopric of Magdeburg, which had tried to claim jurisdiction over the Polish church. Following the Congress of Gniezno, bishoprics were also established in Kraków, Wrocław, and Kołobrzeg, and Bolesław formally repudiated paying tribute to the Holy Roman Empire. Following the death of Holy Roman Emperor Otto III in 1002, Bolesław fought a series of wars against the Holy Roman Empire and Otto's cousin and heir, Henry II, ending in the Peace of Bautzen (1018). In the summer of 1018, in one of his expeditions, Bolesław I captured Kiev, where he installed his son-in-law Sviatopolk I as ruler. According to legend, Bolesław chipped his sword when striking Kiev's Golden Gate. Later, in honor of this legend, a sword called Szczerbiec ("Jagged Sword") would become the coronation sword of Poland's kings.

Bolesław I was a remarkable politician, strategist, and statesman. He not only turned Poland into a country comparable to older western monarchies, but he raised it to the front rank of European states. Bolesław conducted successful military campaigns in the west, south and east. He consolidated Polish lands and conquered territories outside the borders of modern-day Poland, including Slovakia, Moravia, Red Ruthenia, Meissen, Lusatia, and Bohemia. He was a powerful mediator in Central European affairs. Finally, as the culmination of his reign, in 1025 he had himself crowned King of Poland. He was the first Polish ruler to receive the title of rex (Latin: "king").

He was an able administrator who established the "Prince's Law" and built many forts, churches, monasteries and bridges. He introduced the first Polish monetary unit, the grzywna, divided into 240 denarii,[1] and minted his own coinage. Bolesław I is widely considered one of Poland's most capable and accomplished Piast rulers.

Early life

Bolesław was born in 966 or 967,[2] the first child of Mieszko I of Poland and his wife, the Bohemian princess Dobrawa.[3][4] His Epitaph, which was written in the middle of the 11th century, emphasized that Bolesław had been born to a "faithless" father and a "true-believing" mother, suggesting that he was born before his father's baptism.[4][5] Bolesław was baptized shortly after his birth.[6] He was named after his maternal grandfather, Boleslaus I, Duke of Bohemia.[7] Not much is known about Bolesław's childhood. His Epitaph recorded that he underwent the traditional hair-cutting ceremony at the age of seven and a lock of his hair was sent to Rome.[6] The latter act suggests that Mieszko wanted to place his son under the protection of the Holy See.[6][8] Historian Tadeusz Manteuffel says that Bolesław needed that protection because his father had sent him to the court of Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor in token of his allegiance to the emperor.[8] However historian Marek Kazimierz Barański notes that the claim that Bolesław was sent as a hostage to the imperial court is disputed.[9]

Bolesław's mother, Dobrawa died in 977; his widowed father married Oda of Haldensleben who had already been a nun.[10][11] Around that time, Bolesław became the ruler of Lesser Poland, through it is not exactly clear in what circumstances. Jerzy Strzelczyk says that Bolesław received Lesser Poland from his father; Tadeusz Manteuffel states that he seized the province from his father with the local lords' support; and Henryk Łowmiański writes that his uncle, Boleslav II of Bohemia, granted the region to him.[12]

Accession and consolidation

Mieszko I died on 25 May 992.[13][14] The contemporaneous Thietmar of Merseburg recorded that Mieszko left "his kingdom to be divided among many claimants", but Bolesław unified the country "with fox-like cunning"[15] and expelled his stepmother and half-brothers from Poland.[16][17] Two Polish lords Odilien and Przibiwoj,[18] who had supported her and her sons, were blinded on Bolesław's order.[17] Historian Przemysław Wiszniewski says that Bolesław had already taken control of the whole of Poland by 992;[19] Pleszczyński writes that this only happened in the last months of 995.[16]

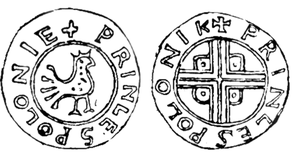

Bolesław's first coins were issued around 995.[20] One of them bore the inscription Vencievlavus, showing that he regarded his mother's uncle Duke Wenceslaus I of Bohemia as the patron saint of Poland.[21] Bolesław sent reinforcements to the Holy Roman Empire to fight against the Polabian Slavs in summer 992.[22][23] Bolesław personally led a Polish army to assist the imperial troops in invading the land of the Abodrites or Veleti in 995.[22][23][24] During the campaign, he met the young German monarch, Otto III.[25]

Soběslav, the head of the Bohemian Slavník dynasty, also participated in the 995 campaign.[26] Taking advantage of Soběslav's absence, Boleslav II of Bohemia invaded the Slavníks' domains and had most members of the family murdered.[27] After learning of his kinsmen's fate, Soběslav settled in Poland.[28][16] Bolesław gave shelter to him "for the sake of [Soběslav's] holy brother",[29] Bishop Adalbert of Prague, according to the latter's hagiographies.[30] Adalbert (known as Wojciech before his consecration)[31] also came to Poland in 996, because Bolesław "was quite amicably disposed towards him".[32][30] Adalbert's hagiographies suggest that the bishop and Bolesław closely cooperated.[33] Early 997 Adalbert left Poland to proselytize among the Prussians who had been invading the easter borderlands of Bolesław's realm.[24][33] However, the pagans murdered him on 23 April 997.[33] Bolesław ransomed Adalbert's remains, paying its weight in gold, and buried it in Gniezno.[9][33][34] He sent parts of the martyr bishop's corpse to Emperor Otto III who had been Adalbert's friend.[34]

Congress of Gniezno and its aftermath (999–1002)

Emperor Otto III held a synod in Rome where Adalbert was canonized on the emperor's request on 29 June 999.[33][35] Before 2 December 999, Adalbert's brother, Radim Gaudentius, was consecrated "Saint Adalbert's archbishop".[35][36] Otto III made a pilgrimage to Saint Adalbert's tomb in Gniezno, accompanied by Pope Sylvester II's legate, Robert, in early 1000.[37][38] Thietmar of Merseburg mentioned that it "would be impossible to believe or describe"[39] how Bolesław received the emperor and conducted him to Gniezno.[40] A century later, Gallus Anonymus added that "[m]arvelous and wonderful sights Bolesław set before the emperor when he arrived: the ranks first of the knights in all their variety, and then of the princes, lined up on a spacious plain like choirs, each separate unit set apart by the distinct and varied colors of its apparel, and no garment there was of inferior quality, but of the most precious stuff that might anywhere be found."[40][41]

Bolesław took advantage of the emperor's pilgrimage.[42] After the Emperor's visit in Gniezno, Poland started to develop into a sovereign state, in contrast with Bohemia, which remained a vassal state, incorporated in the Kingdom of Germany.[43] Thietmar of Merseburg condemned Otto III for "making a lord out of a tributary"[44] in reference to the relationship between the Emperor and Bolesław.[45] Gallus Anonymus emphasized that Otto III declared Bolesław "his brother and partner" in the Holy Roman Empire, also calling Bolesław "a friend and ally of the Roman people".[46][37][40] The same chronicler mentioned that Otto III "took the imperial diadem from his own head and laid it upon the head of Bolesław in pledge of friendship"[46] in Gniezno.[40] Bolesław also received "one of the nails from the cross of our Lord with the lance of St. Maurice"[46] from the Emperor.[37][40]

Gallus Anonymus claimed that Bolesław was "gloriously raised to kingship by the emperor"[47] through these acts, but the Emperor's acts in Gniezno only symbolized that Bolesław received royal prerogatives, including the control of the Church in his realm.[40] Radim Gaudentius was installed as the archbishop of the newly established Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Gniezno.[36] At the same time, three suffragan bishoprics, subordinated to the see of Gniezno – the dioceses of Kołobrzeg, Kraków and Wrocław – were set up.[48] Bolesław had promised that Poland would pay Peter's Pence to the Holy See to obtain the pope's sanction to the establishment of the new archdiocese.[42] Unger, who had been the only prelate in Poland and was opposed to the creation of the archdiocese of Gniezno, was made bishop of Poznań, directly subordinated to the Holy See.[49] However, Polish commoners only slowly adopted Christianity: Thietmar of Merseburg recorded that Bolesław forced his subjects with severe punishments to observe fasts and to refrain from adultery.[50]

If anyone in this land should presume to abuse a foreign matron and thereby commit fornication, the act is immediately avenged through the following punishment. The guilty party is led on to the market bridge, and his scrotum is affixed to it with a nail. Then, after a sharp knife has been placed next to him, he is given the harsh choice between death or castration. Furthermore, anyone found to have eaten meat after Septuagesima is severely punished, by having his teeth knocked out. The law of God, newly introduced in these regions gains more strength from such acts of force than from any fast imposed by the bishops

During the time the Emperor spent in Poland, Bolesław also showed off his affluence.[45] At the end of the banquets, he "ordered the waiters and the cupbearers to gather the gold and silver vessels ... from all three days' coursis, that is, the cups and goblets, the bowls and plates and the drinking-horns, and he presented them to the emperor as a toke of honor ... [h]is servants were likewise told to collect the wall-hangings and the coverlets, the carpets and tablecloths and napkins and everything that had been provided for their needs and take them to the emperor's quarters",[47] according to Gallus Anonymus.[45] Thietmar of Merseburg recorded that Bolesław presented Otto III with a troop of "three hundred armoured warriors".[52][49] Bolesław also gave Saint Adalbert's arm to the Emperor.[49]

After the meeting, Bolesław escorted Otto III to Magdeburg in Germany where "they celebrated Palm Sunday with great festivity"[53] on 25 March 1000.[54] A continuator of the chronicle of Adémar de Chabannes recorded, decades after the events, that Bolesław also accompanied Emperor Otto from Magdeburg to Aachen where Otto III had Charlemagne's tomb reopened and gave Charlemagne's golden throne to Bolesław.[49][55][56]

An illustrated Gospel, made for Otto III around 1000, depicted four women symbolizing Roma, Gallia, Germania and Sclavinia as doing homage to the Emperor who sat on his throne.[55] Historian Alexis P. Vlasto writes that "Sclavinia" referred to Poland, proving that it was regarded as one of the Christian realms subjected to the Holy Roman Empire in accordance with Otto III's idea of Renovatio imperii[55] – the renewal of the Roman Empire based on a federal concept.[57] Within that framework, Poland, along with Hungary, was upgraded to an eastern foederatus of the Holy Roman Empire, according to historian Jerzy Strzelczyk.[57]

Coins struck for Bolesław shortly after his meeting with the emperor bore the inscription Gnezdun Civitas, showing that he regarded Gniezno as his capital.[55] The name of Poland was also recorded on the same coins referring to the Princes Polonie [sic].[55] The title princeps was almost exclusively used in Italy around that time, suggesting that it also represented the Emperor's idea of the renewal of the Roman Empire.[55] However, Otto's premature death on 23 January 1002 put an end to his ambitious plans.[54] The contemporaneous Bruno of Querfurt stated that "nobody lamented" the 22-year-old emperor's "death with greater grief than Bolesław".[58][59]

Expansion (1002–1019)

Three candidates were competing with each other for the German royal crown after Otto III's death.[60] One of them, Duke Henry IV of Bavaria, promised the Margraviate of Meissen to Bolesław in exchange for his assistance against Eckard I, Margrave of Meissen who was the most powerful contender.[60] However, Eckard was murdered on 30 April 1002, which enabled Henry of Bavaria to defeat his last opponent, Herman II, Duke of Swabia.[60] Fearing that Henry II would side with elements in the German Church hierarchy, which were unfavorable towards Poland,[61] and taking advantage of the chaos that followed Margrave Eckard's death and Henry of Bavaria's conflict with Henry of Schweinfurt, Bolesław invaded Lusatia and Meissen.[42][62] He "seized Margrave Gero's march as far as the river Elbe",[63] and also Bautzen, Strehla and Meissen.[64] At the end of July, he participated at a meeting of the Saxon lords where Henry of Bavaria, who had meanwhile been crowned king of Germany, only confirmed Bolesław's possession of Lusatia, and granted Meissen to Margrave Eckard's brother, Gunzelin, and Strehla to Eckard's oldest son, Herman.[65][66] The relationship between King Henry and Bolesław became tense after assassins tried to murder Bolesław in Merseburg, because he accused the king of the conspiracy against him.[65][66] In retaliation, he seized and burned Strehla and took the inhabitants of the town into captivity.[65]

Duke Boleslaus III of Bohemia was dethroned and the Bohemian lords made Vladivoj, who had earlier fled to Poland, duke in 1002.[65] The Czech historian Dušan Třeštík writes that Vladivoj seized the Bohemian throne with Bolesław's assistance.[67] After Vladivoj died in 1003, Bolesław invaded Bohemia and restored Boleslaus III who had many Bohemian noblemen murdered.[68][65] The Bohemian lords who survived the massacre "secretly sent representatives" to Bolesław, asking "him to rescue them from fear of the future",[69] according to Thietmar of Merseburg.[68] Bolesław invaded Bohemia and had Boleslaus III blinded.[65] He entered Prague in March 1003 where the Bohemian lords proclaimed him duke.[70][71] King Henry sent his envoys to Prague, demanding Bolesław to take an oath of loyalty and to pay tribute to him, but Bolesław refused to obey.[66][70] He also allied himself with the king's opponents, including Henry of Schweinfurt to whom he sent reinforcements.[72] King Henry defeated Henry of Schweinfurt, forcing him to flee to Bohemia in August 1003.[73] Bolesław invaded the Margraviate of Meissen, but Margrave Gunzelin refused to surrender his capital.[73] It is also likely that Polish forces took control of Moravia and Upper Hungary (present day Slovakia) in 1003 as well. The proper conquest date of the Hungarian territories is 1003 or 1015 and this area stayed a part of Poland until 1018.[74]

King Henry allied himself with the pagan Lutici,[71] and broke into Lusatia in February 1004, but heavy snows forced him to withdraw.[68][73] He invaded Bohemia in August 1004, taking the oldest brother of the blinded Boleslaus III of Bohemia, Jaromír, with him.[73] The Bohemians rose up in open rebellion and murdered the Polish garrisons in the major towns.[73] Bolesław left Prague without resistance, and King Henry made Jaromír duke of Bohemia on 8 September.[73] Boleslaw's ally Soběslav died in this campaign.[71]

During the next part of the offensive King Henry retook Meissen and in 1005, his army advanced as far into Poland as the city of Poznań where a peace treaty was signed.[75] According to the peace treaty Bolesław lost Lusatia and Meissen and likely gave up his claim to the Bohemian throne. Also in 1005, a pagan rebellion in Pomerania overturned Boleslaw's rule and resulted in the destruction of the just implemented local bishopric.[76]

In 1007, King Henry denounced the Peace of Poznań, which caused Bolesław's attack on the Archbishopric of Magdeburg as well as the re-occupation of the marches of Lusatia, through he stopped short of retaking Meissen.[71] The German counter-offensive began three years later, in 1010, but it was of no significant consequence.[71] In 1012, a five-year peace was signed. Bolesław broke the peace, however, and once again invaded Lusatia. Bolesław's forces pillaged and burned the city of Lubusz (Lebus).[75] In 1013, a peace accord was signed at Merseburg.[71] As part of the treaty, Bolesław paid homage to King Henry for the March of Lusatia (including the town of Bautzen) and Sorbian Meissen as fiefs.[71] A marriage of Bolesław's son Mieszko with Richeza of Lotharingia, daughter of the Count Palatine Ezzo of Lotharingia and granddaughter of Emperor Otto II, was also performed.[71] During the brief period of peace on the western frontier that followed, Bolesław took part in a short campaign in the east, towards the Kievan Rus' territories.[71]

In 1014, Bolesław sent his son Mieszko to Bohemia in order to form an alliance with Duke Oldrich against Henry, by then crowned emperor.[71] Oldrich imprisoned Mieszko and turned him over to Henry, who however released him in a gesture of good will.[71] Bolesław nonetheless refused to aid the emperor militarily in his Italian expedition.[71] This led to imperial intervention in Poland and so in 1015 a war erupted once again.[71] The war started out well for the emperor, as he was able to defeat the Polish forces at the Battle of Ciani.[77] Once the imperial forces crossed the river Oder, Bolesław sent a detachment of Moravian knights in a diversionary attack against the Eastern March of the empire. Soon after, the imperial army, having suffered a defeat near the Bóbr marshes, retreated from Poland without any permanent gains.[71] After this event, Bolesław's forces took the initiative. Margrave Gero II of Meissen was defeated and killed during a clash with the Polish forces in late 1015.[78][79]

Later that year, Bolesław's son Mieszko was sent to plunder Meissen. His attempt at conquering the city, however, failed.[75] In 1017, Bolesław defeated Duke Henry V of Bavaria. In that same year, supported by his Slavic allies, Emperor Henry once again invaded Poland, however, once again to very little effect.[71] He did besiege the cities of Głogów and Niemcza, but was unable to conquer them.[71] The imperial forces once again were forced to retreat, suffering significant losses.[71] Taking advantage of the involvement of Czech troops, Bolesław ordered his son to invade Bohemia, where Mieszko met very little resistance.[80] On 30 January 1018, the Peace of Bautzen was signed. The Polish ruler was able to keep the contested marches of Lusatia and Sorbian Meissen not as fiefs, but as a part of Polish territory,[71] and also received military aid in his expedition against Kievan Rus.[81] Also, Bolesław (then a widower) strengthened his dynastic bonds with the German nobility through his marriage with Oda, daughter of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen. The wedding took place four days later, on 3 February in the castle of Cziczani (also Sciciani, at the site of either modern Groß-Seitschen[82] or Zützen).[83]

War in Kiev

Bolesław organized his first expedition east, to support his son-in-law Sviatopolk I of Kiev, in 1013, but the decisive engagements were to take place in 1018 after the peace of Budziszyn was already signed.[84] At the request of Sviatopolk I, in what became known as the Kiev Expedition of 1018m the Polish duke send an expedition Kievan Rus' with an army of between 2,000–5,000 Polish warriors, in addition to Thietmar's reported 1,000 Pechenegs, 300 German knights, and 500 Hungarian mercenaries.[85] After collecting his forces during June, Boleslaw led his troops to the border in July and on 23 July at the banks of the Bug River, near Wołyń, he defeated the forces of Yaroslav the Wise prince of Kiev, in what became known as the Battle at Bug river. All primary sources agree that the Polish prince was victorious in battle.[86][87] Yaroslav retreated north to Novgorod, rather than to Kiev. The victory opened the road to Kiev.[84] The city, which suffered from fires caused by the Pecheneg siege, surrendered upon seeing the main Polish force on 14 August.[88] The entering army, led by Bolesław, was ceremonially welcomed by the local archbishop and the family of Vladimir I of Kiev.[89] According to popular legend Bolesław notched his sword (Szczerbiec) hitting the Golden Gate of Kiev.[89] Although Sviatopolk lost the throne soon afterwards and lost his life the following year,[89] during this campaign Poland re-annexed the Red Strongholds, later called Red Ruthenia, lost by Bolesław's father in 981.[84]

Last years (1019–1025)

Historians dispute the exact date of Bolesław's coronation. Some believe that since the year 1000, the Polish ruler asked the Pope to consent to his coronation, following the Congress of Gniezno. Independent German sources clearly confirmed that after Henry II's death in 1024, Bolesław took advantage of the interregnum in Germany and crowned himself king in 1025. The exact date and place of the coronation remain unknown. It is generally assumed that the coronation took place on Easter, exactly on 18 April, although Tadeusz Wojciechowski believes that the coronation took place already on 24 December 1024.[90] The basis for this assertion is that the coronations of kings were usually held during religious festivities. It is most likely that the place for the coronation was Gniezno. Poland was thus raised to the rank of a kingdom before its neighbor Bohemia. Others (like Johannes Fried) believe that the coronation of 1025 was only the renewal of a previous coronation performed in 1000 (multiple coronations were common at the time).

Wipo of Burgundy in his Chronicle describes this event:

[In 1025] Boleslaus [of the Slavic nation], duke of the Poles, took for himself in injury to King Conrad the regal insignia and the royal name. Death swiftly killed his temerity.

.jpg)

Hence it is assumed that Bolesław received permission for his coronation from Pope John XIX, who at that point had a bad relationship with the Holy Roman Empire. Stanisław Zakrzewski put forward the theory that the coronation had the tacit consent of Conrad II and that the pope only confirmed this fact. This is corroborated by Conrad's confirmation of the royal title to Mieszko II, his agreement with the counts of Tusculum, and the papal interactions with Conrad and Bolesław.[92]

Bolesław I died shortly after his coronation on 17 June, most likely from an illness. The location of Boleslaw's burial site is uncertain. According to Jan Długosz (and followed by modern historians and archaeologists), he was buried in the Archcathedral Basilica of St. Peter and St. Paul, Poznań. In the 14th century, King Casimir III the Great reportedly ordered the construction of a Gothic sarcophagus, to which he transferred Boleslaw's remains.

The sarcophagus was partially destroyed in 1772 during a fire, and completely destroyed a few years later in 1790 due to the collapse of the south tower. Then, the remains were moved to the Chapter house, where three bone fragments where donated to Tadeusz Czacki (in 1801, at his request). Czacki, a notable Polish historian, pedagogue, and numismatist, placed one of the bone fragments in his ancestral mausoleum in Poryck (now Pavlivka) in the Volhynia region; the other two were given to Princess Izabela Czartoryska née Flemming, who placed them in her recently founded Czartoryski Museum in Puławy. After many historical twists, the burial place of Bolesław I ultimately remained at Poznań Cathedral, in the Golden Chapel.[93] The content of his epitaph is known to historians. It is Bolesław's epitaph, which, in part, came from the original tombstone, that is one of the first sources (dated to the period immediately after Bolesław's death, probably during the reign of Mieszko II[94]) that gave the King his widely known nickname of "Brave" (Polish: Chrobry) -later Gallus Anonymus in the Chapter 6 of his Gesta principum Polonorum named the Polish ruler as Bolezlavus qui dicebatur Gloriosus seu Chrabri.

Family

The contemporaneous Thietmar of Merseburg recorded Bolesław's marriages, also mentioning his children.[95] Bolesław's first wife was a daughter of Rikdag, Margrave of Meissen.[95][9] Historian Manteuffel says that the marriage was arranged in the early 980s by Mieszko I who wanted to strengthen his links with the Saxon lords and to enable his son to succeed Rikdag in Meissen.[96] Bolesław "later sent her away",[18] according to Thietmar's Chronicon.[95] Historian Marek Kazimierz Barański writes that Bolesław repudiated his first wife after her father's death in 985 which left the marriage without any political value.[9]

Bolesław "took a Hungarian woman"[18] as his second wife.[95] Most historians identify her as a daughter of the Hungarian ruler Géza, but this theory has not been universally accepted.[97] She gave birth to a son, Bezprym, but Bolesław repudiated her.[95]

Bolesław's third wife, Emnilda, was "a daughter of the venerable lord, Dobromir".[18][95] Her father was a West Slavic or Lechitic prince, either a local ruler from present-day Brandenburg who was closely related to the imperial Liudolfing dynasty,[22] or the last independent prince of the Vistulans, before their incorporation into Poland.[9] Wiszewski dates the marriage of Bolesław and Emnilda to 988.[3] Emnilda exerted a beneficial influence on Bolesław, forming "her husband's unstable character",[18] according to Thietmar of Merseburg's report.[95] Bolesław's and Emnilda's oldest (unnamed) daughter "was an abbess"[18] of an unidentified abbey.[3] Their second daughter Regelinda, who was born in 989, was given in marriage to Herman I, Margrave of Meissen in 1002 or 1003.[3] Mieszko II Lambert who was born in 990[3] was Bolesław's favorite son and successor.[98] The name of Bolesław's and Emnilda's third daughter, who was born in 995, is unknown; she married Sviatopolk I of Kiev between 1005 and 1012.[3] Bolesław's youngest son, Otto, was born in 1000.[3]

Bolesław's fourth marriage, from 1018 until his death, was to Oda (c. 995 – 1025), daughter of Margrave Eckard I of Meissen. They had a daughter, Matilda (c. 1018 – 1036), betrothed (or married) on 18 May 1035 to Otto of Schweinfurt.

See also

- Bolesław Chrobry Tournament – speedway event named after the King

- Castle Chrobry in Szprotawa

- History of Poland (966–1385)

References

- A. Czubinski, J. Topolski, Historia Polski, Ossolineum, 1989.

- Tymieniecki Kazimierz, Bolesław Chrobry. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja. Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. ISBN 83-04-00148-9. Page 248

- Wiszewski 2010, p. xliii.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 115.

- Wiszewski 2010, pp. 57, 60.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. 63.

- Barford 2001, p. 163.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 51.

- Barański 2008, p. 51, 60–68.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 52.

- Wiszewski 2010, pp. xliii, 35.

- Wiszewski 2010, pp. 8–9.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 55.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. xlii.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 4.58.), p. 192.

- Pleszczyński 2001, p. 417.

- Manteuffel 1982, pp. 56–57.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 4.58.), p. 193.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. xxxvii.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 145.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, pp. 144–145.

- Pleszczyński 2001, p. 416.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 56.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 125.

- Vlasto 1970, pp. 124–125.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 57.

- Manteuffel 1982, pp. 57–58.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 58.

- Life of Saint Adalbert Bishop of Prague and Martyr (ch. 25.), p. 165.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. 13.

- Barford 2001, p. 255.

- Life of Saint Adalbert Bishop of Prague and Martyr (ch. 26.), p. 167.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 60.

- Vlasto 1970, pp. 104–105.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 105.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 61.

- Barford 2001, p. 264.

- Vlasto 1970, pp. 125–126.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 4.45.), p. 183.

- Pleszczyński 2001, p. 419.

- The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles (ch. 6.), p. 35.

- Thompson 2012, p. 21.

- Zamoyski 1987, p. 14.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 5.10.), p. 212.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 62.

- The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles (ch. 6.), p. 37.

- The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles (ch. 6.), p. 39.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 121.

- Pleszczyński 2001, p. 420.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 122.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 8.2), p. 362.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 4.46.), p. 184.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 4.46.), p. 185.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 63.

- Vlasto 1970, p. 127.

- Zamoyski 1987, p. 13.

- Strzelczyk 2003, p. 24.

- Life of the Five Brethren by Bruno of Querfurt (ch. 8.), p. 237.

- Pleszczyński 2001, p. 421.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 64.

- Tymieniecki Kazimierz, Bolesław Chrobry. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja. Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. ISBN 83-04-00148-9. Page 250

- Manteuffel 1982, pp. 64–65.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 5.9.), p. 211.

- Thompson 2012, pp. 21–22.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 65.

- Reuter 2013, p. 260.

- Třeštík 2011, p. 78.

- Berend, Urbańczyk & Wiszewski 2013, p. 142.

- The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (ch. 5.30.), p. 225.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 66.

- Tymieniecki Kazimierz, Bolesław Chrobry. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja. Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. ISBN 83-04-00148-9. Page 251

- Manteuffel 1982, pp. 66–67.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 67.

- Makk, Ferenc (1993). Magyar külpolitika (896–1196) ("The Hungarian External Politics (896–1196)"). Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Műhely. pp. 48–49. ISBN 963-04-2913-6.

- Thietmar of Merseburg, Thietmari merseburgiensis episcopi chronicon, 1018

- Jan M Piskorski, Pommern im Wandel der Zeiten, 1999, p.32, ISBN 83-906184-8-6 OCLC 43087092

- "Bitwa pod Ciani, bo nie chce mi się". Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Olszowski, Michał. "historycy.org -> Bolesław Chrobry - "pan na Morawach"". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- "Czy Bolesław Chrobry podbił Słowację?". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Zajączkowski, Grzegorz. "Włącz Polskę- Polska-szkola.pl". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- "Bolesław Chrobry: legalny władca Czech czy uzurpator - Czasopisma - Onet.pl Portal wiedzy". Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Michael Schmidt. "Digitales historisches Ortsverzeichnis von Sachsen". Hov.isgv.de. Retrieved 12 January 2013.

- Elke Mehnert, Sandra Kersten, Manfred Frank Schenke, Spiegelungen: Entwürfe zu Identität und Alterität ; Festschrift für Elke Mehnert, Frank & Timme GmbH, 2005, p.481, ISBN 3-86596-015-4

- Tymieniecki Kazimierz, Bolesław Chrobry. In: Konopczyński Władysław (ed): Polski słownik biograficzny. T. II: Beyzym Jan – Brownsford Marja. Kraków: Nakładem Polskiej Akademii Umiejętności, 1936. ISBN 83-04-00148-9. Page 252

- R.Jaworski,Wyprawa Kijowska Chrobrego, 2006

- Cross, Samuel Hazzard; Sherbowitz-Wetzor, Olgerd, eds. The Russian Primary Chronicle: Laurentian Text, 1953

- Anonymous Gaul,Cronicae et gesta ducum sive principum Polonorum

- Wyprawa Kijowska Chrobrego Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 2. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 5 August 2006. P. 10

- Wyprawa Kijowska Chrobrego Chwała Oręża Polskiego Nr 2. Rzeczpospolita and Mówią Wieki. Primary author Rafał Jaworski. 5 August 2006. P. 11

- Tadeusz Wojciechowski: Szkice historyczne jedynastego wieku, ed. III. 1951, p. 153.

- The Deeds of Conrad II (Wipo) (ch. 9.), p. 75.

- Wipo: Gesta Chuonradi II imperatoris, p. 34.

- Michał Rożek, Adam Bujak: Nekropolie królów i książąt polskich, Warsaw 1988, pp. 12–14.

- Przemysław Wiszniewski: Domus Bolezlai. W poszukiwaniu tradycji dynastycznej Piastów (do około 1138 roku), Wrocław 2008, p. 62.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. 39.

- Manteuffel 1982, p. 53.

- Wiszewski 2010, p. 376.

- Manteuffel 1982, pp. 77–78.

Sources

Primary sources

- "Life of the Five Brethren by Bruno of Querfurt (Translated by Marina Miladinov)" (2013). In Saints of the Christianization Age of Central Europe (Tenth-Eleventh Centuries) (Edited by Gábor Klaniczay, translated by Cristian Gaşpar and Marina Miladinov, with an introductory essay by Ian Wood) [Central European Medieval Texts, Volume 6.]. Central European University Press. pp. 183–314. ISBN 978-615-5225-20-8.

- "Life of Saint Adalbert Bishop of Prague and Martyr (Translated by Cristian Gaşpar)" (2013). In Saints of the Christianization Age of Central Europe (Tenth-Eleventh Centuries) (Edited by Gábor Klaniczay, translated by Cristian Gaşpar and Marina Miladinov, with an introductory essay by Ian Wood) [Central European Medieval Texts, Volume 6.]. Central European University Press. pp. 77–182. ISBN 978-615-5225-20-8.

- Ottonian Germany: The Chronicon of Thietmar of Merseburg (Translated and annotated by David A. Warner) (2001). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4926-1.

- "The Deeds of Conrad II (Wipo)" (2000). In Imperial Lives & Letters of the Eleventh Century (Translated by Theodor E. Mommsen and Karl F. Morrison, with a historical introduction and new suggested readings by Karl F. Morrison, edited by Robert L. Benson). Columbia University Press. pp. 52–100. ISBN 978-0-231-12121-7.

- The Deeds of the Princes of the Poles (Translated and annotated by Paul W. Knoll and Frank Schaer with a preface by Thomas N. Bisson) (2003). CEU Press. ISBN 963-9241-40-7.

Secondary sources

- Barański, Marek Kazimierz (2008). Dynastia Piastów w Polsce [The Piast Dynasty in Poland] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. ISBN 978-83-01-14816-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The Early Slavs: Culture and Society in Early Medieval Eastern Europe. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Berend, Nora; Urbańczyk, Przemysław; Wiszewski, Przemysław (2013). Central Europe in the High Middle Ages: Bohemia, Hungary and Poland, c. 900-c. 1300. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78156-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Norman (2005). God's Playground: A History of Poland, Volume I: The Origins to 1795 (Revised Edition). Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12817-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Manteuffel, Tadeusz (1982). The Formation of the Polish State: The Period of Ducal Rule, 963–1194 (Translated and with an Introduction by Andrew Gorski). Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1682-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pleszczyński, Andrzej (2001). "Poland as an ally of the Holy Ottonian Empire". In Urbańczyk, Przemysław (ed.). Europe around the Year 1000. Wydawnictwo DIG. pp. 409–425. ISBN 83-7181-211-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reuter, Timothy (2013). Germany in the Early Middle Ages, c. 800–1056. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-582-49034-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosik, Stanisław (2001). Bolesław Chrobry i jego czasy [Bolesław the Brave and his Times] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Dolnośląskie. ISBN 978-83-70-23888-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strzelczyk, Jerzy (2003). "Die Anfänge Polens und Deutschlands". In Lawaty, Andreas; Orłowski, Hubert (eds.). Deutsche und Polen: Geschichte-Kultur-Politik (in German). Verlag C. H. Beck. pp. 16–25. ISBN 978-3-406-49436-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thompson, James Westfall (2012). "Medieval German expansion in Bohemia and Poland". In Berend, Nóra (ed.). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Ashgate Variorum. pp. 1–38. ISBN 978-1-4094-2245-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Třeštík, Dušan (2011). "Great Moravia and the beginnings of the stte (9th and 10th centuries)". In Pánek, Jaroslav; Tůma, Oldřich (eds.). A History of the Czech Lands. Charles University in Prague. pp. 65–79. ISBN 978-80-246-1645-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Vlasto, A. P. (1970). The Entry of the Slavs into Christendom: An Introduction to the Medieval History of the Slavs. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-10758-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wiszewski, Przemysław (2010). Domus Bolezlai: Values and Social Identity in Dynastic Traditions of Medieval Poland (c. 966–1138). Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-18142-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zamoyski, Adam (1987). The Polish Way: A Thousand-year History of the Poles and their Culture. Hippocrene Book. ISBN 0-7818-0200-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

Bolesław I the Brave Piast Dynasty Born: 966 or 967 Died: 17 June 1025 | ||

| Preceded by Mieszko I |

Duke of the Polans 25 May 992 – 17 June 1025 King of Poland (since 18 April 1025) |

Succeeded by King Mieszko II Lambert |

| Preceded by Odo II |

Margrave of Saxon Eastern March 1002–1025 |

Succeeded by Mieszko II |

| Preceded by Vladivoj |

Duke of Bohemia 1003–1004 |

Succeeded by Jaromír |