Zabrze

Zabrze (/ˈzɑːbʒeɪ/; Polish pronunciation: [ˈzabʐɛ] (![]()

Zabrze | |

|---|---|

Main Post Office | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

Zabrze  Zabrze | |

| Coordinates: 50°18′09″N 18°46′41″E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | |

| County | city county |

| Established | thirteenth century |

| Town rights | 1922 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Małgorzata Mańka-Szulik |

| Area | |

| • City | 80.40 km2 (31.04 sq mi) |

| Population (31 December 2019) | |

| • City | 172,360 |

| • Urban | 2,746,000 |

| • Metro | 4,620,624 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 41-800 to 41-820 |

| Area code(s) | +48 32 |

| Car plates | SZ |

| Website | https://www.um.zabrze.pl |

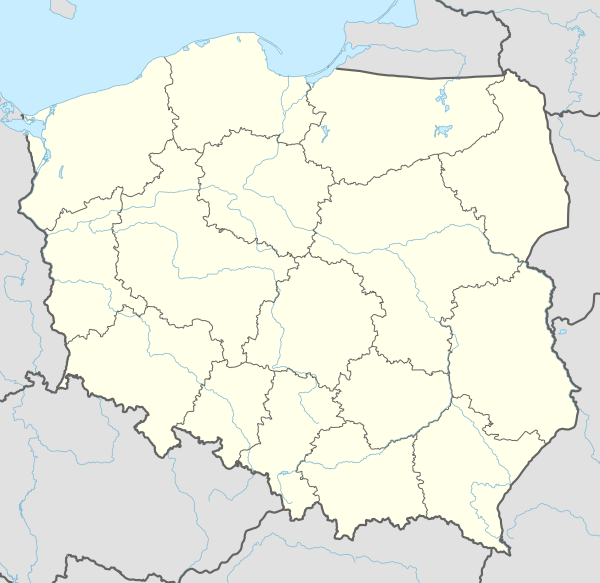

Zabrze is located in the Silesian Voivodeship, which was reformulated in 1999. Before 1999 it was in Katowice Voivodeship. It is one of the cities composing the 2.7 million inhabitant conurbation referred to as the Katowice urban area, itself a major centre in the greater Silesian metropolitan area which is populated by just over five million people.[2] The population of Zabrze as of December 2019 is 172,360, down from June 2009 when the population was 188,122.[1]

History

Early history

Biskupice (Biskupitz), which is now a subdivision of Zabrze, was first mentioned in 1243 as Biscupici dicitur cirka Bitom. Zabrze (or Old Zabrze) was mentioned in 1295-1305 as Sadbre sive Cunczindorf (German for Konrad/Kunze's village; sive = "or"). In the Late Middle Ages, the local Silesian Piast dukes invited German settlers into the territory, resulting in increasing German settlement. The settlement was part of the Silesian duchies of fragmented Poland. Zabrze became part of the Habsburg Monarchy of Austria in 1526, and was later annexed by the Kingdom of Prussia during the Silesian Wars. In 1774, the Dorotheendorf settlement was founded. When the first mine in Zabrze became operational in 1790, the town became an important mining center. In the 19th century, new coal mines, steelworks, factories and a power plant were created. A road connecting Gliwice and Chorzów and a railway connecting Opole and Świętochłowice were led through Zabrze.

Early 20th century

In 1905, the Zabrze commune was formed by the former communes Alt-Zabrze, Klein-Zabrze and Dorotheendorf. The Zabrze commune was renamed Hindenburg in 1915 in honour of Generalfeldmarschall Paul von Hindenburg. The name change was approved by Emperor Wilhelm II on 21 February 1915.[3] Up till then, it was one of the few cities whose Polish name was retained during German rule.

In 1904 the "Sokół" Polish Gymnastic Society in Zabrze was established, which was also a Polish patriotic and pro-independence organization.[4] As a result of the Prussian harassment it was liquidated in 1911, but it was reactivated twice, in 1913 and 1918.[5][4] Its members took an active part in the post-war plebiscite campaign and the Silesian uprisings.[4]

Interwar period

During the plebiscite held after World War I, 21,333 inhabitants (59%) of the Hindenburg commune voted to remain in Germany, while 14,873 (41%) voted for incorporation to Poland, which just regained its independence.[3] In May 1921 the Third Silesian Uprising broke out and Hindenburg was captured by Polish insurgents, who held it until the end of the uprising.[3] When Upper Silesia was divided between Poland and Germany in 1921, the Hindenburg commune remained in Germany. It received its city charter in 1922. Just five years after receiving city rights Hindenburg became the biggest city in German-ruled western Upper Silesia and the second biggest city in German-ruled Silesia after Wrocław (then Breslau). Nevertheless, various Polish organizations still operated in the city in the interbellum, including a local branch of the Union of Poles in Germany,[6] Polish libraries, sports clubs, credit unions, choirs, scout troops and an amateur theater.[7] Polish newspaper Głos Ludu was published in the city.[8] In a secret Sicherheitsdienst report from 1934, Zabrze was named one of the main centers of the Polish movement in western Upper Silesia.[9] In terms of religion, most of the city's population adhered to the Catholic Church.[10]

In the 1920s, the communists, Christian democrats and nationalists enjoyed the greatest support among the German population, while Poles supported Polish parties.[11] In 1928, among the largest cities in western Upper Silesia, Polish parties received the most votes in Zabrze.[7] In the March 1933 elections, most of the citizens voted for the Nazi Party, followed by Zentrum and the Communist Party. Nazi politician Max Fillusch became the city's mayor and remained in the position until 1945.[12]

The anti-Polish organization Bund Deutscher Osten was very active in the city, it dealt with propaganda, indoctrination and espionage of the Polish community, as well as denouncing Poles to local authorities.[13] When, the Barbórka (traditional holiday of miners) church services were organized separately for Poles and Germans in 1936, the Polish service enjoyed a greater attendance,[14] however, due to Nazi oppression and propaganda, the attendance at Polish services in the 1930s gradually decreased, according to Bund Deutscher Osten.[15] Polish activists were increasingly persecuted since 1937.[6] People were urged to Germanise their names, Polish inscriptions were removed from tombstones.[13] Some Polish priests were expelled from the city, both before[16] and during World War II.[17] As a result of German persecution the Jewish community dropped from 1,154 people in 1933 to 551 in 1939, and its remainder was deported to Nazi concentration camps in 1942.[10] The town's synagogue, that had stood since 1872, was destroyed in the Kristallnacht pogroms of November 1938.[18]

World War Two

During World War II, in 1941 the German administration requisitioned church property, in which it removed Polish symbols and memorabilia.[19] Church bells were confiscated for war purposes in 1942.[20] The Germans established three working parties of the Stalag VIII-B/344 prisoner-of-war camp in the city,[21] and also a subcamp of Auschwitz III was located there.

In January 1945, the Soviets captured the city and afterwards deported some inhabitants to the Soviet Union, while some of the German inhabitants were expelled west.

Contemporary history

Following World War II, according to the Potsdam Agreement the city was handed over to Poland in 1945 and the town's name was changed to the historic Zabrze on 19 May 1945. The first post-war mayor of Zabrze was Paweł Dubiel, pre-war Polish activist and journalist in Upper Silesia, prisoner of the Dachau and Mauthausen Nazi concentration camps during the war.[22] The pre-war Polish inhabitants of the region, who formed the majority of the city's population in 1948,[23] were joined by Poles expelled from former eastern Poland annexed by the Soviet Union.

The city limits were largely expanded in 1951, by including Mikulczyce, Rokitnica, Grzybowice, Makoszowy, Kończyce and Pawłów as new districts.[23] New neighbourhoods were built from the 1950s to 1990s.[23] In 1948, Górnik Zabrze football club was founded, which won its first Polish championship in 1957, and soon became the pride of the city as one of the most successful clubs in Poland.

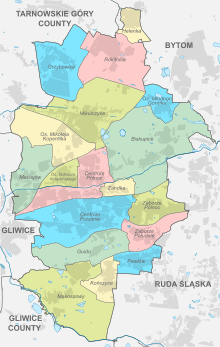

Administrative division

On 17 September 2012, the Zabrze city council decided on a new administrative division of the city. Zabrze was subsequently divided into 15 districts and 3 housing estates.[24]

- 1. Helenka

- 2. Grzybowice

- 3. Rokitnica

- 4. Mikulczyce

- 5. Młody Górnik estate

- 6. Mikołaj Kopernik estate

- 7. Biskupice

- 8. Maciejów

- 9. Tadeusz Kotarbiński estate

- 10. Centrum Północ

- 11. Centrum Południe

- 12. Guido

- 13. Zaborze Północ

- 14. Zaborze Południe

- 15. Pawłów

- 16. Kończyce

- 17. Makoszowy

- 18. Zandka

Infrastructure

The Polish A4, which is part of the European E40, has a motorway junction near Zabrze. The Drogowa Trasa Srednicowa leads through the town.

Culture and sights

Among the cultural institutions of the town are the Zabrze Philharmonic and Teatr Nowy ("New Theatre"). Dom Muzyki i Tańca ("House of Music and Dance") indoor arena is located in Zabrze. The local museums are the Coal Mining Museum, the Municipal Museum and the Military Technology Museum. The Maciej mine shaft and the Main Key Adit (Główna Kluczowa Sztolnia Dziedziczna), one of the longest such structures in Europe, are open for tourists.

Among the historical architecture there are many industrial facilities, as well as various churches, houses, public buildings, etc. There are also numerous monuments referring to the history of the city, especially the Silesian Uprisings fought here and World War II.

There is also a botanical garden and several parks in Zabrze.

Coal Mining Museum

Coal Mining Museum- New Theatre

- Maciej mine shaft

Main Key Adit

Main Key Adit Monument to the Heroes of Monte Cassino

Monument to the Heroes of Monte Cassino Botanical garden

Botanical garden

Politics

Members of Parliament (Sejm) elected from Bytom/Gliwice/Zabrze constituency

- Chojnacki Jan, SLD-UP

- Dulias Stanisław, Samoobrona

- Gałażewski Andrzej, PO

- Janik Ewa, SLD-UP

- Kubica Józef, SLD-UP

- Martyniuk Wacław, SLD-UP

- Okoński Wiesław, SLD-UP

- Szarama Wojciech, PiS

- Szumilas Krystyna, PO

- Widuch Marek, SLD-UP

Sports

The city's most renown sports team is Górnik Zabrze, one of the most accomplished Polish football clubs, 14 times Polish champions, 6 times Polish Cup winners, and 1969–70 European Cup Winners' Cup runners-up, as the only Polish team to reach the final stage of a major European football competition. Other popular team is NMC Górnik Zabrze, two times Polish men's handball champions and three times Polish Cup winners. Both teams compete in the national top leagues, the Ekstraklasa and Superliga respectively.

Many sportspeople were born in Zabrze, including footballers Łukasz Skorupski and Adam Bodzek, and pro ice hockey player of the National Hockey League, Wojtek Wolski.

Economy

Like other towns in this populous region, it is an important manufacturing centre, having coal-mines, iron, wire, glass, chemical and oil works, and local Upper Silesia Brewery, etc.

Notable people

- Karl Godulla (1781–1848), Prussian industrialist

- James Kleist (1873-1949), German-American Jesuit scholar

- Heinz Fiebig (1897–1964), Wehrmacht general

- Fritz Katz (1898–1969), pioneer of adrenal transplants

- Wolfgang Jörchel (1907–1945), Standartenführer in the Waffen SS

- Władysław Turowicz (1908–1980), Polish-Pakistani military scientist

- Fritz Laband (1925–1982), German footballer

- Friedrich Nowottny (born 1929), German television journalist

- Janosch (born 1931), German author

- Joachim Kroll (1933–1991), German serial killer

- Joachim Kerzel (born 1941), German actor

- Jan Sawka (1946–2012), Polish-American artist, architect

- Krystian Zimerman (born 1956), internationally renowned classical pianist, was born here in 1956.

- Waldemar Sorychta (born 1967), Polish heavy metal musician and producer

- Czesław Śpiewa, (born 1979), Polish singer

- Wojtek Wolski (born 1986), Polish-Canadian ice-hockey player playing in the NHL

- Margarete Stokowski (born 1988), Polish-German writer

- The Dumplings, electropop band[25]

Twin towns – sister cities

References

- "Local Data Bank". Statistics Poland. Retrieved 25 June 2020. Data for territorial unit 2478000.

- European Spatial Planning Observation Network (ESPON)

- Historia - Hindenburg at the official website of Zabrze

- "Polskie Towarzystwo Gimnastyczne "Sokół" w Zabrzu, Historia Zabrza". Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Encyklopedia powstań śląskich, Instytut Śląski w Opolu, Opole, 1982, p. 637

- Cygański 1984, p. 24.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 74.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 124.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 60.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 35.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 53-54.

- Stadtkreis Zabrze at Geschichte on Demand website

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 50.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 130.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 157.

- Cygański 1984, p. 26.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 100.

- Ghetto Fighters' House archives, Photo No. 55805: a memorial monument placed by the Zabrze municipality in 1998 to commemorate its Jewish community.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 102.

- Rosenbaum & Węcki 2010, p. 105.

- "Working Parties". Stalag VIIIB 344 Lamsdorf. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Dubiel Paweł Mikołaj (1902-1980)". Biblioteka Sejmowa (in Polish). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- "Okres powojenny". Urząd Miasta Zabrze (in Polish). Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- Zestawienie liczby mieszkańców z uwzględnieniem podziału na dzielnice na dzień: 30-09-2013.

- "The Dumplings — Free listening, videos, concerts, stats and photos at Last.fm". www.last.fm. Retrieved 19 May 2016.

- "Miasta partnerskie i zaprzyjaźnione". um.zabrze.pl (in Polish). Zabrze. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

Bibliography

- Cygański, Mirosław (1984). "Hitlerowskie prześladowania przywódców i aktywu Związków Polaków w Niemczech w latach 1939 - 1945". Przegląd Zachodni (in Polish) (4).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rosenbaum, Sebastian; Węcki, Mirosław (2010). Nadzorować, interweniować, karać. Nazistowski obóz władzy wobec Kościoła katolickiego (1934–1944). Wybór dokumentów (in Polish). Katowice: IPN. ISBN 978-83-8098-299-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zabrze. |

- Municipal website (in Polish)

- Zabrze Community (in Polish)

- Portal Zabrze.com.pl (in Polish)

- Encyclopædia Britannica Zabrze

- Jewish Community in Zabrze on Virtual Shtetl

- Old images of the city (in German)

- http://www.zabrze.aplus.pl/