Pope–Leighey House

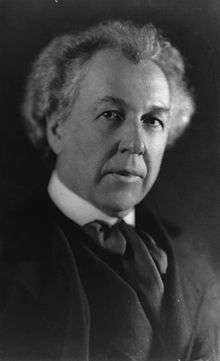

The Pope–Leighey House, formerly known as the Loren Pope Residence, is a suburban home in Virginia designed by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright. The house, which belongs to the National Trust for Historic Preservation, has been relocated twice and sits on the grounds of Woodlawn Plantation, Alexandria, Virginia. Along with the Andrew B. Cooke House and the Luis Marden House, it is one of the three homes in Virginia designed by Frank Lloyd Wright.

Pope–Leighey House | |

| |

| |

| Location | East of Accotink off US 1, near Alexandria, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 38°43′9.95″N 77°8′9.53″W |

| Built | 1941 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Usonian |

| NRHP reference No. | 70000791[1] |

| VLR No. | 029-0058 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 18, 1970 |

| Designated VLR | October 6, 1970[2] |

Conception

Commissioned in 1939 by journalist Loren Pope and his wife Charlotte Pope, the design followed Wright's Usonian principles and was completed in 1941 at an official cost of $7,000 (original target price was $5,000)[3] — at 1005 Locust Street, Falls Church, Virginia.[4][5]

Loren Pope, at the time a writer for the Washington Evening Star had grown interested in Wright after studying his Wasmuth Portfolio, a 1938 Time Magazine article and Wright's recently published autobiography.[3] Pope met Wright in 1938 when the architect made a presentation in D.C. while working on another project that would remain un-built. Pope approached Wright at his presentation, indicating he'd like Wright to design his home. Wright indicated that he did not design speculative work, rather only designed homes for "people who deserved them."[3]

Pope subsequently wrote the architect, beginning his letter "Dear Mr. Wright, There are certain things a man wants during life, and of life. Material things and things of the spirit. The writer has one fervent wish that includes both. It is a house created by you."[3] After Wright agreed, Pope subsequently visited another Usonian home of Wright's design and met Wright at Taliesin. The architect originally designed a house of 1,800 square feet (170 m2). Mr. Pope at the time made $50 per week, and borrowing the money for the house proved difficult, with one lender counseling Pope the home would be a "white elephant."[3] Pope's employer, the Evening Star, eventually offered a loan of $5,700 and construction commenced after Wright sized the plan down from 1800 sf to 1200 sf.[3]

In May 1941, less than 2 months after the Pope’s moved in, their 3 year old son Ned died when he wandered out of the house and drowned in a neighbor’s pond.[6] Pope and his family lived in the house for 6 years, moving in 1946 to a 365-acre farm in Loudoun County,[3] planning to subsequently build a larger Wright-designed home. Limitations on his income precluded Pope from affording the new home until 1959, when Wright was busy with the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

Design

The design follows Wright's Usonian model of well-designed space for middle-income residents with a design that brings nature inside, using modest materials and a flat roof.

The home's L-shaped layout features two bedrooms and a bathroom in one wing and living and dining areas in the other. At the juncture of the two wings are the home's entrance, a study, and the kitchen. The home was designed on a 2 by 4 feet (0.61 by 1.22 m) rectangular grid scored into a concrete floor painted in Wright's signature color, Cherokee Red. To accommodate the original site's slope, the house features two levels.

The living room features a ceiling at eleven-and-a half feet (3.5 m), the bedroom wing opens outward with tall glass doors and windows, and the house features a patterned ribbon of clerestory windows at the top of the walls. Materials included Tidewater red cypress (finished in clear wax), brick, and glass. The entire house features radiant heating with hot water pipes embedded in the concrete slab. The furniture was designed by Wright.

Construction

Wright assigned apprentice Gordon Chadwick to oversee construction of the home,[3] though Wright himself visited the house several times. Wright felt the house's construction was costing the owner too much and did not request his final payment. Wright, who wanted to name the home "Touchstone,"[3] felt the design was one of the best representations of his Usonian ideals.[3] Howard Rickert from Vienna, Virginia, was the project's primary carpenter.[3]

First Relocation

The Popes sold the home to Robert and Marjorie Leighey in 1946. In 1961, the state of Virginia informed the Leigheys the house would be condemned to make way for Interstate 66. Robert died in 1963, and Marjorie Leighey donated the home to the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 1964, along with the entire $31,500 condemnation award to help pay for the relocation.[7] Before donating the home, Ms. Leighey had turned down the initial condemnation award of $25,605 from the Virginia Highway Department.[8]

The home was dismantled, moved, and reconstructed on the property of Woodlawn Plantation, 9000 Richmond Highway, Alexandria, Virginia, where it opened to the public as the Pope–Leighey House in 1965.[9] Leighey continued to reside in the home from 1969 until her death in 1983.

.jpg)

Second Relocation

The house had initially been poorly located at Woodlawn Plantation — over an area with unstable marine clay. In 1995, the house was again relocated[10] thirty feet[11] at a cost of $500,000.[11]

References

- "National Register of Historical Places - VIRGINIA - Fairfax County". National Park Service.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 5 June 2013.

- "The Pope–Leighey House An Interview with Loren Pope". National Building Museum, Steven M. Reiss, AIA, 2006.

- Terry B. Morton, "The Threat, Rescue, and Move," in The Pope–Leigh[e]y House (Washington DC: National Trust for Historic Preservation, 1969), p. 106.

- Sargent, Sarah (December 20, 2010). "Affordable Housing". Virginia Living. Cape Fear Publishing. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- Paul Hendrickson, "Plagued By Fire: the Dreams and Furies of Frank Lloyd Wright," (New York: Alfred A. Knoff, 2019), p. 28.

- "The Pope–Leighey House". Delmars.com.

- Franklin, Ben A. (20 March 1964). "House by Wright Faces Demolition". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Pope–Leighey House, National Trust for Historic Preservation". Archived from the original on 2019-01-27. Retrieved 2010-05-19.

- "The Pope–Leighey House".

- "Small Frank Lloyd Wright House Moved for $500,000". NPR, Morning Edition, September 14, 1995.

Fifty-five years ago Frank Lloyd Wright built the Pope–Leighey House for $7,000. It is now being moved 30 feet away... at a cost of more than half a million dollars.

Further reading

- Steven M. Reiss. Lloyd Wright's Pope–Leighey House (University of Virginia Press; 2014) 216 pages

- The Pope–Leigh[e]y House. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Washington, DC. 1969. LC 74-105251.

- Storrer, William Allin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University Of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2 (S.268)

External links

- Pope–Leighey House, 9000 Richmond Highway (moved from Falls Church, VA), Mount Vernon, Fairfax County, VA: 33 photo, 9 measured drawings, 6 data pages, and 2 photo caption pages at Historic American Buildings Survey

- Frank Lloyd Wright's Pope–Leighey House. National Trust for Historic Preservation website

- Call Number: HABS VA,30-FALCH,2- American Memory from the Library of Congress

- Photos on Arcaid

- Pope–Leighey House on dgunning.org

- Pope–Leighey House on peterbeers.net

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pope-Leighey House. |

- Andrew B. Cooke House, Virginia Beach, Virginia

- Marden House, Mclean, Virginia

- Chronological list of Frank Lloyd Wright works

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works by location