Robert and Rae Levin House

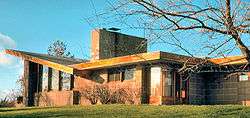

In 1949, Robert and Rae Levin worked with Frank Lloyd Wright to build a house in Kalamazoo, Michigan. It was the first house to be built in Parkwyn Village, a planned community of Usonian houses. Usonia is a word used by Frank Lloyd Wright and refers to the residents of the United States Of North America.[1] Those houses were meant for the common man at that time.[1] The finished house was constructed of textile blocks, big windows and skylights, built-in furniture, and a mix of shallow and grand sloping ceilings. Wright designed the house to be connected closely to nature.[1]

| Robert and Rae Levin House | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | House |

| Architectural style | Usonian |

| Location | Kalamazoo, Michigan |

| Coordinates | 42.262816°N 85.632425°W |

| Construction started | 1949 |

| Design and construction | |

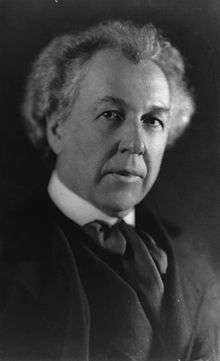

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

Beginning Process

In the early 1940s, a group of employees from the Upjohn Company began to meet and plan for a new cooperative community in Kalamazoo. They were looking for a design that was inexpensive yet practical, and a community where decisions were made equally.[2] The group began to search for land and interview architects. After interviewing architects they asked for their opinion as to what architect would be the best for the job, and they all said Frank Lloyd Wright, but that he would never agree to work with them.

The group contacted Wright between 1946 and 1947 requesting his involvement in their community. By phone the group explained their ideas and were invited to Taliesin to explain their ideas more thoroughly. Part of the group went to present their ideas. Even though it was a small task during this period of his career, Wright accepted the job.[2]

After Wright agreed to work with them, they began recruiting other families to become part of their community. Potential families had to attend a Parkwyn Association meeting before they could buy land within the community. The association was not allowed to discriminate against race, religion, or color.[1] By November 1948 there were 26 families.

The group then found 72 acres (290,000 m2) of land in Galesburg, ten miles (16 km) away from Kalamazoo. Some wanted to live there, but others wanted to live closer to town. Soon the group split into two, those who wanted to live closer to the city, and those who wanted to live in Galesburg, often called "The Acres" or "Galesburg Country Homes". The families wanting to live closer to town found 47 acres (190,000 m2) and called their community “Parkwyn Village”. Although the two groups were not living in the same location, they worked together to promote both communities.[3]

During 1947 both plattes were designed, and sent to the Federal Housing Administration for approval. Wright planned circular lots for Parkwyn Village so there would be shared space between each house, but later changed them to rectangles after having the lots denied by the FHA for financing. Even though technically the area between each house was not shared, the owners planted trees and flowers between the properties to honor the original plans.[1]

The plan included space for community owned property. That area included an outdoor grill, picnic tables, swings, teeter-totters, tennis courts, an ice-skating rink, a baseball diamond, swimming pool, and a community center. Some of these amenities were forgotten and never completed.[2]

Wright also planned for a circular road pattern to build a stronger sense of community, and underground utilities so there would be no curbs, gutters, sewers, or above ground telephone wires.[2]

Textile Blocks

Textile blocks are concrete blocks designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and were used to build the Levin House. Some blocks contained patterns and some had cut outs with glass inserted, to allow light to filter through.

The Association was told there was going to be a machine to help with the making of the blocks. A machine was never made available to them like Wright said.[4] An engineer, who was part of the Parkwyn Association, built a mold for making the concrete blocks. First, concrete was poured into the mold, and then the mold was removed and the block was set outside to cure overnight. Proper curing strengthens the blocks and makes them more durable. Water is needed to cure the blocks and the closest supply was from the nearby pond, so that was the water used.[4] The color added to the blocks was a mix of red and yellow, creating a shade of orange. Rae Levin chose the color for the blocks. Unskilled laborers were hired from a local university to make the blocks. They were mostly college students interested in the project.[4] Over 15,000 blocks were built.[4]

Due to the pond water, a white residue was left on the blocks. The unskilled laborers did not understand that the blocks were not going to be covered by plaster or wallpaper but were going to be seen from the inside.[4] The discoloration was an annoyance to the owners.[4]

The house was assembled without mortar between the bricks, but with a steel rod for the inner foundation. This method of assembling the blocks was also used for the Imperial Hotel.

Money

Wright, after meeting with the two groups, agreed to an average house price of $15,000. The end price turned out to be much higher than Wright had estimated.[4]

The 47 acres (190,000 m2) of land cost $18,000. The roads cost $7,000. The under-ground electricity cost $9,000. The telephone wiring cost $1,600. The water system cost $10,000. Surveying of the land cost $1,500. The surveying of the land after the FHA denied the circular lots cost $600. The tennis courts cost $2,772.[4]

Finished House

As with many of the Usonian houses, Wright used a large amount of glass, wide roof overhangs, large fireplaces, open interiors, spacious terraces, and outdoor living facilities. He did not like the idea of a house being like a cardboard box, so his designs were far from four walls and a single flat roof.[1] A Usonian house was intended to be "a thing loving the ground with the new sense of space, light, and freedom."

Wright used natural light to help dramatize forms and textures. In the Levin house there were many grand windows, as well as smaller cut-outs that light could shine through in the textile bricks.

To help simplify the house, the garage became an open-carport, radiators became radiant heat, and paint was not used in favor of natural wood. Wright also reduced the need for free standing furniture by creating built-in furniture.[2]

The original finished house consisted of three bedrooms, two baths, a study, a living room, a dining room, a screened in porch, and a small basement utility room. In the original plans the kitchen was labeled as a workspace that included the clothes washer and dryer. Later a family room, two bedrooms, and a basement were added to the house.[4]

Life in the House

James Levin, son of Robert and Rae Levin, remembers people knocking at the door wanting to see his home. About once a month students and others interested in Wright's work would ask for a tour of the Levin House.[4]

Because Wright designed his homes to be horizontal with the surrounding environment, his roofs were flat, causing them to leak.[1] After a snowfall, the Levins would climb onto the roof to shovel snow off it.[4] Wright made the Usonian houses feel like a comfortable shelter by lowering the ceilings to “human proportions”. [1] In a section of the Levin House, the roof is about five feet from the ground, when outside. The Levin children loved the low roof because in the winter they would jump off of it and into the snow banks.[4]

The most frequent complaint in the Usonian homes was the kitchen.[1] Wright didn't think big kitchens were important.[1] The homeowners disliked the small size and lack of view to the outside.

Originally there was no attic or basement. In place of a garage there was a carport. The house had very little storage space, but there was a small shed accessible from the outside that the Levins used to store pickles.[4]

See also

- Frank Lloyd Wright buildings

- Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works by date

- List of Frank Lloyd Wright works by location

- Broadacre City

- Usonia

Notes

- Chamberlain, Laura. "Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Communities in Kalamazoo County, Michigan." Kalamazoo Historic Preservation Commission, 1999.

- McCartney, Heather. Parkwyn Village. Kalamazoo, 1976.

- Peterson, Kelly. "Wright Around Kalamazoo." History of Kalamazoo Today Nov. 2003: 8-12.

- Robert and Rae Levin (speakers) (September 2000). 2000 Annual Conference: "Broadacre City and Beyond: Frank Lloyd Wright's Vision for Usonia" (Videotape). Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy.

The Creation of Parkwyn Village, A Miniature Broadacre City in Kalamazoo, Michigan

References

- Hoag, Edwin (1977), Masters of Modern Architecture, Indianapolis: the Bobbs-Merrill company, ISBN 0-672-52338-8

- Sergeant, John (1976), Frank Lloyd Wright's Usonian Houses, New York: Whitney Library of Design, ISBN 0-8230-7177-4

- Storrer, William Allin. The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University Of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2 (S.298)

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Levin House. |

- Kalamazoo Public Library: Frank Lloyd Wright Houses