Hillside Home School II

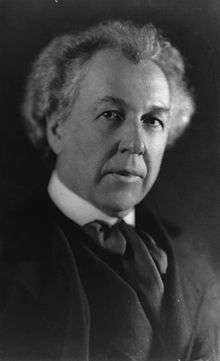

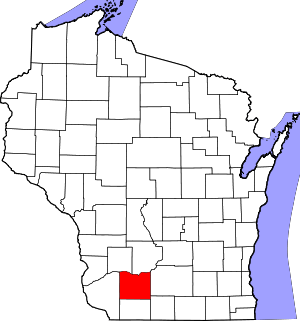

The Hillside Home School II was originally designed by architect Frank Lloyd Wright in 1901 for his aunts Jane and Ellen C. Lloyd Jones in the town of Wyoming, Wisconsin (south of the village of Spring Green). The Lloyd Jones sisters commissioned the building to provide classrooms for their school, also known as the Hillside Home School. The Hillside Home School structure is on the Taliesin estate, which was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1976. There are four other Wright-designed buildings on the estate (also National Historic Landmarks): the Romeo and Juliet Windmill tower, Tan-y-Deri, Midway Barn, and Wright's home, Taliesin.

The Hillside Home School | |

The Hillside Home School on the Taliesin Estate | |

| Location | South of Spring Green, in Iowa County, Wisconsin |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 43°08′30″N 90°04′15″W |

| Built | 1901-03, 1932, 1952 |

| Architect | Frank Lloyd Wright |

| Architectural style | Prairie School |

| Visitation | 25,000 (2019) |

| Website | "Hillside Home School". |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000081 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | March 14, 1973 |

| Designated CP | January 7, 1976 |

History

The Hillside Home School institution was a nonsectarian, coeducational, day and boarding school for children from first through twelfth grade[1] (Wright would start his home, Taliesin north of the school, 10 years later, in 1911). This structure was the third building he would design for his aunts. He designed the first building, Hillside Home School I, in 1887,[2] and the second one, Romeo and Juliet Windmill Tower, in 1896.

The Weekly Home News (Spring Green's newspaper) reported on October 17, 1901, that: "Owing to the increased attendance, the principals have decided to build a new schoolhouse. The plans have been drawn and sent from the studio of Frank Ll. Wright, architect, Chicago, and work upon the construction will begin at once." The "Home News" then reported on February 19, 1903, that the building would be complete by "the last day of April".

The Hillside Home School institution ran from 1887 until 1915.[3] Educator Mary Ellen Chase taught at the Hillside Home School for three years in the beginning of her career (1910–1913). She later wrote about her experiences in the book, The Goodly Fellowship:

I suppose that the Hillside Home School were it existing today as it was existing in 1909, would be termed a progressive school by all the supporters and disciples of such institutions. Yet the charm and value of Hillside lay in the fact that it did not standoff and gaze complacently at itself as a pioneer in the new education. In other words, it lacked the self-consciousness as well as the self-righteousness of certain of our modern experiments in child growth instead of child discipline... It was simply a school, a home, and a farm all in one....[4]

Jane and Ellen Lloyd Jones closed the school in 1915, and the grounds were purchased by Frank Lloyd Wright, who wrote about the "acute financial distress"[5] of the Lloyd Jones sisters and their school:

There seemed no way out; no one to help. So I did. To "pay up" and give them a little rest—rest so much needed but which no one, least of all myself, believed they knew how to take. They wanted to turn everything over to me, asking me to promise that their work would continue. I promised. That promise comforted them.[6]

Taliesin Fellowship

In 1932, Wright was able to use the Hillside Home School building for his newly established Taliesin Fellowship (now the School of Architecture at Taliesin[7]). He and his apprentices in the Fellowship converted the old gymnasium on the west side of the original Hillside Home School structure into a theater. On the north end of the original Hillside Home School structure, he added a large drafting room with dormitories on either side (left).[8][9] The original theater was re-designed and reconstructed after the original one was destroyed by fire in 1952 (rebuilt theater, lower left).[10]

In 1941, architectural historian, Henry-Russell Hitchcock described the Hillside Home School building in his book, In the Nature of Materials:

The construction is unusually solid for this period of Wright's work, comparing thus with the contemporary Heurtley house. The lower walls are of native rock-faced random ashlar, superbly laid and reminding one of the finest of Richardson's masonry. But the stone was light and flesh-colored and has remained so in this country environment so that the effect is not grim or even severe. The marked batter of the pavilion walls serves to centralize and concentrate their design. This batter was used on the Imperial Hotel fifteen years later. It also appears once more in the rough stone and concrete bases of Taliesin West, 1938, and the Pauson house, 1940, near Phoenix, Arizona.[11]

The drafting studio at Hillside became Wright's main Wisconsin studio after World War II.[12] As a result, most of Wright's commissions and building designs were worked on in this studio while Wright was in Wisconsin in the summer. These designs include:

- First Unitarian Society Meeting House

- Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum

- Price Tower

- "The Illinois", a project for a mile-high building, in 1956.[13]

References

- http://www.steinerag.com/flw/Artifact%20Pages/PCSprgGreen.htm

- William Allin Storrer. The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2 (S.367), p. 3.

- Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Frank Lloyd Wright Complete Works, Vol. 1: 1885–1916, Taschen, 2009, p. 154.

- Mary Ellen Chase, A Goodly Fellowship (The Macmillan Company, New York City, 1939), Chapter 3, "I Seek My Fortune in the Middle West", p. 93-94.

- Frank Lloyd Wright. 1943 addition to An Autobiography in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, volume 4: 1939-49. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1994). 125.

- Frank Lloyd Wright. 1943 addition to An Autobiography in Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, volume 4: 1939-49. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1994). 125.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on April 3, 2019. Retrieved September 29, 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM25967

- https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM25968

- William Allin Storrer, The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion, p. 232.

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, 1887–1941: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright (New York, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942), p. 50

- https://www.wisconsinhistory.org/Records/Image/IM131734

- "Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright (1951-1956)".

See Also

- Mary Ellen Chase, A Goodly Fellowship (The Macmillan Company, New York City, 1939).

- Henry-Russell Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, 1887–1941: The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright (New York, Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1942; New York, Da Capo Press, Inc., 1969).

- Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, Frank Lloyd Wright Complete Works Taschen, 2009.

- William Allin Storrer, The Frank Lloyd Wright Companion. University of Chicago Press, 2006, ISBN 0-226-77621-2, (S.069).

External links

- Taliesin Preservation, Inc.

- The School of Architecture at Taliesin – official website.

- The Wright Library – This website has additional Frank Lloyd Wright information; the linked page has descriptions of the original school booklets for the Hillside Home School run by the Lloyd Jones sisters.