Petrovaradin

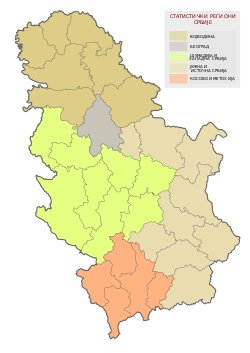

Petrovaradin (Serbian Cyrillic: Петроварадин, pronounced [petroʋarǎdiːn]) is one of two city municipalities which constitute the city of Novi Sad. As of 2011, the urban area has 27,083 inhabitants, while the municipality has 33,865 people inhabitants. Lying across the river Danube from the main part of Novi Sad, it is built around the Petrovaradin Fortress, historical anchor of the modern city.

Petrovaradin | |

|---|---|

Town and city municipality | |

.jpg)   From top: Belgrade's street, Belgrade's Gate, The Our Lady of Snow ecumenic church, Petrovaradin Fortress | |

Coat of arms | |

Petrovaradin Location within Novi Sad | |

| Coordinates: 45°15′N 19°52′E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| District | South Bačka |

| City | |

| Government | |

| • President of the local community | Dušan Popović (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 56.40 km2 (21.78 sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 89.30 km2 (34.48 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 81 m (266 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Urban | 27,083 |

| • Municipality | 33,865 |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 21131 |

| Area code | +381 21 |

| Vehicle registration | ns |

| Website | www |

Name

Petrovaradin was founded by Celts, but its original name is not known. During Roman administration it was known as Cusum. After the Romans conquered the region from the Celtic tribe of Scordisci, they built the Cusum fortress where present Petrovaradin Fortress now stands. In addition, the town received its name from the Byzantines, who called it Petrikon or Petrikov (Πετρικον) and who presumably named it after Saint Peter.

In documents from 1237, the town was first mentioned under the name Peturwarod (Pétervárad), which was named after Hungarian lord Peter, son of Töre. Petrovaradin was known under the name Pétervárad during Hungarian administration, Varadin or Petervaradin during Ottoman administration, and Peterwardein during Habsburg administration.

Today, the municipality is known in Serbian as Петроварадин, in Hungarian as Pétervárad, and in German as Peterwardein.

Geography

Petrovaradin is located in the Syrmia region, on the Danube river and Fruška Gora, a horst mountain with elevation of 78–220 m (municipality up to 451 m). The northern part of Fruška Gora consists of massive landslide zones, but they are not active, except in Ribnjak neighborhood (between Sremska Kamenica and Petrovaradin fortress).

History

Human settlement in the territory of present-day Petrovaradin has been traced as far back as the Stone Age (about 4500 BC). This region was conquered by Celts (in the 4th century BC) and Romans (in the 1st century BC).

The Celts founded the first fortress at this location. It was part of the tribal state of the Scordisci, which had its capital in Singidunum (present-day Belgrade). During the Roman administration, a larger fortress was built (in the 1st century) with the name Cusum and was included into Roman Pannonia. Subsequently, the fortress was included into the Pannonia Inferior and the Pannonia Secunda. In the 5th century, Cusum was devastated by the invasion of the Huns.

The town was then conquered by Ostrogoths, Gepids, and Lombards. By the end of the 5th century, Byzantines had reconstructed the town and called it by the names Cusum and Petrikon or Petrikov. It was part of the Byzantine province of Pannonia. Subsequently, it passed into the hands of Avars, Franks, Pannonian Croats, Pannonian Slavs, Bulgarians, and Byzantines again. During Bulgarian administration, the town was known as Petrik and was part of the domain of duke Sermon, while during subsequent Byzantine administration, it was part of the Theme of Sirmium.

Later, the town became part of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Between 1522 and 1526, Petrovaradin was a base for the early Ŝajkaš regiments, but in 1526, the Ottoman Empire took Petrovaradin after a two-week battle waged against combined forces of Serbs and Hungarians.

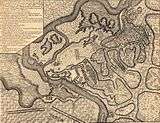

In the war of 1683-1699 with the Habsburg Monarchy, the Ottomans abandoned Petrovaradin. In 1690, they returned for just two years. After that, Petrovaradin remained under Habsburg control.

In 1695, a military force of Serbs—600 infantry and 200 cavalry—under Captain Pane Božić were brought to Petrovaradin to serve. One thousand Serbs worked on the Citadel and fortifications.

During Hungarian administration, the town was firstly part of the Bolgyán County and then part of the Syrmia County, while during Ottoman administration, it was firstly part of the vassal duchy of Syrmia ruled by Serb duke Radoslav Čelnik (1527-1530), and then part of the Sanjak of Syrmia.

During the Ottoman administration, Petrovaradin had 200 houses, and three mosques. There was also a Christian quarter with 35 houses populated with Serbs.

Petrovaradin was the site of a notable battle on August 5, 1716 in which the Habsburg Monarchy led by the Prince Eugene of Savoy defeated the forces of the Ottomans led by the Silahdar Damat Ali Pasha. Habsburg forces led by Prince Eugene later defeated the Ottomans at Belgrade before the Ottomans sued for peace at Požarevac.

During the Habsburg administration, Petrovaradin was part of the Habsburg Military Frontier (Slavonian general command - Petrovaradin regiment). In 1848–49, the town was part of Serbian Vojvodina, but in 1849, it was returned under the administration of the Military Frontier. With the abolishment of the Military Frontier in 1881, the town was included into the Syrmia County of Croatia-Slavonia, which was the autonomous kingdom within Austria-Hungary.

In 1918, the town firstly became part of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, then part of the Kingdom of Serbia and finally part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later known as Yugoslavia). Between 1918 and 1922, the town was part of the Syrmia County, between 1922 and 1929 part of the Syrmia Oblast, and between 1929 and 1941 part of the Danube Banovina, a province of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. From 1918 to 1936, Yugoslav Royal Air Force was based in Petrovaradin. During World War II (1941–1944), the town was occupied by the Axis Powers and it was attached to the Independent State of Croatia. Since the end of the war in this part of Yugoslavia in 1944, the town was part of the Autonomous Province of Vojvodina, which from 1945 was part of the new socialist Serbia within socialist Yugoslavia.

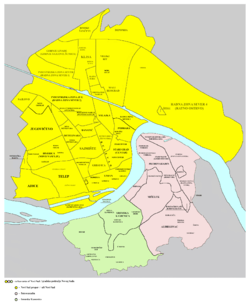

Settlements and neighborhoods

Petrovaradin is one of the two city municipalities of the City of Novi Sad and it is located in the northern Serbian province of Vojvodina. Approximately 25-30% of total area of City of Novi Sad (699 km²) is an area of Petrovaradin municipality, which is approximately 100–130 km²; of which approximately 30% is a part of urban area of Novi Sad. Much of land outside of urban area is part of National Park of Fruška Gora.

Municipality of Petrovaradin includes 5 settlements:

- Town of Petrovaradin

- Town of Sremska Kamenica

- Village of Bukovac

- Village of Ledinci

- Village of Stari Ledinci

Neighborhoods and parts of Petrovaradin are: Petrovaradin Fortress, Podgrađe Tvrđave (which is a fortified part of Petrovaradin and part of Petrovaradin Fortress complex), Stari Majur (which is part of Petrovaradin where offices of Petrovaradin local community are located), Novi Majur, Bukovački Plato (Bukovački Put), Sadovi, Široka Dolina, Širine, Vezirac, Trandžament, Ribnjak, Mišeluk, Alibegovac, Radna Zona Istok, Marija Snežna (Radna Zona Istok), and Petrovaradinska Ada (Ribarska Ada).

Demographics

In 1961 Petrovaradin had 8,408 inhabitants; in 1971 10,477; in 1981 10,338; in 1991 11,285; and in 2002 13,973. By city's registry estimation, from mid-2005, Petrovaradin town had 15,266 inhabitants.[4]

Ethnic groups

- Municipality

According to the 2011 census, the total population of the territory of present-day Petrovaradin municipality was 33,865, of whom 27,328 (80.69%) were ethnic Serbs. All settlements in the municipality have an ethnic Serb majority.

- Town

| Ethnic group | 1991 | % | 2002 | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 5,643 | 50% | 9,708 | 69.48% |

| Croats | 2,236 | 19.81% | 1,364 | 9.76% |

| Yugoslavs | 1,893 | 16.78% | 779 | 5.58% |

| Hungarians | 431 | 3.82% | 396 | 2.83% |

| Montenegrins | 250 | 2.22% | 228 | 1.63% |

| Ruthenians | 148 | 1.31% | 141 | 1.01% |

| Other | 653 | 5.79% | 1,357 | 9.71% |

| Total | 11,285 | - | 13,973 | - |

During the Ottoman administration, Petrovaradin was mostly populated by Muslims, while some Serbs lived there as well in the Christian quarter. According to Habsburg census from 1720, inhabitants of Petrovaradin mostly had German and Serbo-Croatian names and surnames.[5] During the subsequent period of the Habsburg administration and in one part of the 20th century, the largest ethnic group in the Petrovaradin town were ethnic Croats. According to the 1910 census the town had 5,527 residents, of which 3,266 spoke Croatian (59.09%), 894 German (16.18%), 730 Serbian (13.21%), 521 Hungarian (9.43%) and 159 Slovak (2.88%).[6] Since 1971 census, largest ethnic group in Petrovaradin are Serbs. Today, there are a couple of neighborhoods with sizable number of Croats in Petrovaradin, like Stari Majur and Podgrađe Tvrđave.

Economy

The following table gives a preview of total number of employed people per their core activity (as of 2017):[7]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 163 |

| Mining | 12 |

| Processing industry | 1,081 |

| Distribution of power, gas and water | 114 |

| Distribution of water and water waste management | 610 |

| Construction | 373 |

| Wholesale and retail, repair | 1,206 |

| Traffic, storage and communication | 333 |

| Hotels and restaurants | 198 |

| Media and telecommunications | 115 |

| Finance and insurance | 15 |

| Property stock and charter | 3 |

| Professional, scientific, innovative and technical activities | 280 |

| Administrative and other services | 86 |

| Administration and social assurance | 174 |

| Education | 384 |

| Healthcare and social work | 2,252 |

| Art, leisure and recreation | 181 |

| Other services | 117 |

| Total | 7,687 |

Politics

The town of Petrovaradin is the seat of Petrovaradin Municipality. Since 2002, when the new statute of the City of Novi Sad came into effect, it has been divided into two city municipalities, Petrovaradin and Novi Sad. Between 1980 and 1989, Petrovaradin also had municipality status within Novi Sad. From 1989 to 2002, Novi Sad's municipalities were abolished and territory of the former Petrovaradin municipality was part of Novi Sad municipality, which included the whole territory of the present-day City of Novi Sad.

The city municipalities of Novi Sad were formally established in 2002, for the sole reason that Novi Sad could get a city status. In 2007, after the update of the law of local government, the requirement for multiple municipalities for city status was lifted (and 20 additional cities were proclaimed).[8] However, the renewed 2008 city statute also foresaw formation of two separate municipalities, but as of 2009 none of them de facto exist, and the whole city is run solely by the city administration. Petrovaradin municipality does not yet have its own offices,[9] and the town is administered only by local community office.

Culture

Petrovaradin Fortress at night

Petrovaradin Fortress at night Petrovaradin

Petrovaradin- Petrovaradin railway station

- Ribnjak

- The Our Lady of Snow ecumenic church, mostly Catholic, most important Marian shrine in Serbia

- Molinari park

Serbian Orthodox Church of Saint Paul in Petrovaradin

Serbian Orthodox Church of Saint Paul in Petrovaradin City museum in Petrovaradin

City museum in Petrovaradin

Notable people

- Josip Jelačić - Croatian ban and army general, born in Petrovaradin.

- Kosta Nađ, general in the Yugoslav National Liberation Army

See also

- List of places in Serbia

- List of cities, towns and villages in Vojvodina

Notes and references

- Notes

- Petrovaradin, Enciklopedija Novog Sada, knjiga 20, Novi Sad, 2002

- Radenko Gajić, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - Gibraltar na Dunavu, Sremski Karlovci, 1993

- mr Agneš Ozer, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - vodič kroz vreme i prostor, Novi Sad, 2002

- mr Agneš Ozer, Petrovaradin Fortress - A Guide through time and space, Novi Sad, 2002

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradin kroz legendu i stvarnost, Novi Sad, 2001

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradin i Srem - misterija prošlosti, Novi Sad, 2003

- Veljko Milković, Petrovaradinska tvrđava - podzemlje i nadzemlje, Novi Sad, 2005

- Military Heritage did a feature about the Muslim Turks versus Christian Nobility 1716 battle and crusade at Peterwardein, and the success of Prince Eugene of Savoy (Ludwig Heinrich Dyck, Military Heritage, August 2005, Volume 7, No. 1, pp 48 to 53, and p. 78), ISSN 1524-8666.

- Henderson, Nicholas. Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson. 1964

- Mckay, Derek. Prince Eugene of Savoy. London: Thames and Hudson. 1977

- Nicolle, David and Hook, Christa. The Janissaries. Botley: Osprey Publishing. 2000

- Setton, Kenneth M. Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. 1991

- References

- "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 2010-11-28.

- "Насеља општине Петроварадин" (pdf). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

- City's police registry data

- Ivan Jakšić, Iz popisa stanovništva Ugarske početkom XVIII veka, Novi Sad, 1966, pages 309-310.

- Pétervárad. Révai nagy lexikona, vol. 15. p. 387. Hungarian Electronic Library. (in Hungarian).

- ОПШТИНЕ И РЕГИОНИ У РЕПУБЛИЦИ СРБИЈИ, 2018. (PDF). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- Law on Territorial Organization and Local Self-Government Archived 2011-05-13 at the Wayback Machine, Parliament of Serbia (in Serbian)

- "Petrovaradin - opština koje nema" (in Serbian). Radio Television of Vojvodina. 2009-04-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petrovaradin. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Peterwardein. |