Vranje

Vranje (Serbian Cyrillic: Врање, pronounced [ʋrâɲɛ] (![]()

Vranje | |

|---|---|

| City of Vranje | |

.jpg) .jpg) .jpg) From top: Main pedestrian zone, Courthouse in Vranje, County Building, National Museum, Prohor of Pčinja Monastery, White Bridge, Markovo Kale fortress | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

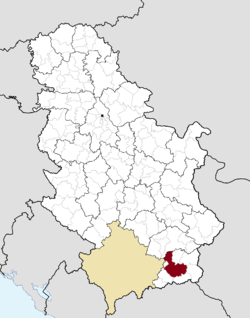

Location of the city of Vranje within Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 42°33′N 21°54′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Southern and Eastern Serbia |

| District | Pčinja |

| Municipalities | 2 |

| Settlements | 105 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Slobodan Milenković (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 36.96 km2 (14.27 sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 860 km2 (330 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 487 m (1,598 ft) |

| Population (2011 census)[2] | |

| • Rank | 17th in Serbia |

| • Urban | 60,485 |

| • Urban density | 1,600/km2 (4,200/sq mi) |

| • Administrative | 83,524 |

| • Administrative density | 97/km2 (250/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 17500 |

| Area code | +381(0)17 |

| ISO 3166 code | SRB |

| Car plates | VR |

| Website | www |

Vranje is the economical, political, and cultural centre of the Pčinja District in Southern Serbia. It is the first city from the Balkans to be declared UNESCO city of Music.[3][4] It is located on the Pan-European Corridor X, close to the borders with North Macedonia and Bulgaria. The Serbian Ortodox Eparchy of Vranje is seated in the city and the 4th Land Force Brigade of the Serbian army is stationed here.

History

The Romans conquered the region in the 2nd or 1st centuries BC. Vranje was part of Moesia Superior and Dardania during Roman rule. The Roman fortresses in the Vranje region were abandoned during the Hun attacks in 539–544 AD; these include the localities of Kale at Vranjska Banja, Gradište in Korbevac and Gradište in Prvonek.[5]

The first written mention of Vranje comes from Byzantine chronicle Alexiad by Anna Comnena (1083–1153), in which it is mentioned how Serbian ruler Vukan in 1093, as part of his conquests, reached Vranje and conquered it, however only shortly, as he was forced to retreat from the powerful Byzantines.[6] The city name stems from the Old Serbian word vran ("black"). The second mention is from 1193, when Vranje was temporarily taken by Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja from the Byzantines.[6] Vranje definitely entered the Serbian state in 1207 when it was conquered by Grand Prince Stefan Nemanjić.[6]

Some time before 1306, tepčija Kuzma was given the governorship of Vranje (a župa, "county", including the town and neighbouring villages), serving King Stefan Milutin.[7] At the same time, kaznac Miroslav held the surroundings of Vranje.[8] Next, kaznac Baldovin (fl. 1325–45) received the province around Vranje, serving King Stefan Dečanski.[9] Next, župan Maljušat, Baldovin's son, held the župa of Vranje.[10] By the time of the proclamation of the Serbian Empire, holders with the title kefalija are present in Vranje, among other cities.[11] During the fall of the Serbian Empire, Vranje was part of Uglješa Vlatković's possessions, which also included Preševo and Kumanovo. Uglješa became a vassal of Serbian Despot Stefan Lazarević after the Battle of Tripolje (1403); Vranje became part of Serbian Despotate.

The medieval župa was a small landscape unit, whose territory expanded with creation of new settlements and independence of hamlets and neighbourhoods from župa villages and shepherd cottages.[6] Good mercantile relations with developing mine city Novo Brdo led to creation of numerous settlements.[6] In 1455, Vranje was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, amid the fall of the medieval Serbian state.[6] It was organized as the seat of a kaza (county), named Vranje, after the city and the medieval župa.[6] In the mid-19th century Austrian diplomat Johann Georg von Hahn stated that the population of Vranje kaza was 6/7 Bulgarian and 1/7 Albanian, while the city population consisted of 1000 Christian-Bulgarian families, 600 Albanian-Turkish and 50 Romani.[12][13] The urban Muslim population of Vranje consisted of Albanians and Turks, of which a part were themselves of Albanian origin.[14]

The report of the Austrian diplomat must be taken with utmost reserve. Austrian diplomat, apart from a tendency to satisfy Bulgarian allay ambitions for those regions (the two world wars witness those tendencies), was probably guided by the fact that the region of Vranje was Ottoman Kyustendil 'kaza' which large eastern parts were indeed populated by the Bulgarians. Kyustendil was the Turkified name of the 14th-century local feudal Serbian Constantine Dragaš; at that time, the region itself was Serbian region. Indeed, number of sources clearly show that the region has been inhabited by the Serbs for more than 10 centuries. Such is Charter of Stefan Uroš IV Dušan, 1308 – 1355,;[15] or, a monograph about the Turkish “censuses” from 1487, 1519, 1570, 1861, confirming that the population of Vranje was Serbe,.[16] There also exist 4 lists of the inhabitants of Vranje in the 19th century (1858, 1869, 1883 and 1890) where Bulgarians are never mentioned. Yet, it is not easy to distinguish Serbs from the Bulgarians only by their names even up to 1878, but after this date almost all names are clearly Serbian names.[17]

Vranje was part of the Ottoman Empire until 1878, when the town was captured by the Serbian army commanded by Jovan Belimarković.[6] During the Serbian–Ottoman War (1876–1878) most of the Muslim population of Vranje fled to the Ottoman vilayet of Kosovo while a smaller number left after the conflict.[14] The city entered the Principality of Serbia, with little more than 8,000 inhabitants at that time.[6] The only Muslim population permitted to remain after the war in the town were Serbian speaking Muslim Romani of whom in 1910 numbered 6,089 in Vranje.[18] Up until the end of the Balkan Wars Vranje had a special position and role, as the transmissive station of Serbian state political and cultural influence on Macedonia.[19]

In the early 20th century, Vranje had around 12,000 inhabitants. As a border town of the Kingdom of Serbia, it was used as the starting point for Serbian guerrilla (Chetniks) who crossed into Ottoman territory and fought in Kosovo and Macedonia. In World War I, the main headquarters of the Serbian army was in the town. King Peter I Karađorđević, Prime Minister Nikola Pašić and the chief of staff General Radomir Putnik stayed in Vranje. Vranje was occupied by the Kingdom of Bulgaria on 16–17 October 1915, after which war crimes and Bulgarisation was committed on the city and wider region.[20]

After the war, Vranje was part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes in one of the 33 oblasts; in 1929, it became part of the Vardar Banovina. During World War II, Nazi German troops entered the town on 9 April 1941 and transferred it to Bulgarian administration on 22 April 1941. During Bulgarian occupation, 400 Serbs were shot and around 4,000 interned. Vranje was liberated by the Yugoslav Partisans on 7 September 1944.

During Socialist Yugoslavia, Vranje was organized into the Pčinja District. In the 1960s and 1970s it was industrialized. During the 1990s, the economy of Vranje was heavily affected by the sanctions against Serbia and the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

Geography

Vranje is situated in the northwestern part of the Vranje basin, on the left waterside of the South Morava.[6]

Vranje is at base of the mountains Pljačkovica (1,231 metres (4,039 feet)), Krstilovice (1,154 metres (3,786 feet)) and Pržar (731 metres (2,398 feet)). The Vranje river and the city are divided by the main road and railway line, which leads to the north Leskovac (70 km), Niš (110 kilometres (68 miles)) and Belgrade (347 kilometres (216 miles)), and, to the south Kumanovo (56 kilometres (35 miles)), Skopje (91 kilometres (57 miles)) and Thessalonica (354 kilometres (220 miles)). It is 70 km (43 mi) from the border with Bulgaria, 40 km (25 mi) from the border with North Macedonia.

Vranje is the economical, political, and cultural centre of the Pčinja District in South Serbia.[6] The Pčinja District also includes the municipalities of Bosilegrad, Bujanovac, Vladičin Han, Preševo, Surdulica, and Trgovište.[6] It is located on the Pan-European Corridor X.

Climate

| Climate data for Vranje (1981–2010, extremes 1961–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 17.9 (64.2) |

22.4 (72.3) |

26.3 (79.3) |

31.5 (88.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

37.9 (100.2) |

41.6 (106.9) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.6 (96.1) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

18.7 (65.7) |

41.6 (106.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.2 (39.6) |

6.8 (44.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.3 (63.1) |

22.5 (72.5) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.7 (83.7) |

29.1 (84.4) |

24.2 (75.6) |

18.4 (65.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.1 (41.2) |

17.1 (62.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

1.8 (35.2) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.2 (52.2) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.8 (53.2) |

5.7 (42.3) |

1.2 (34.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −3.6 (25.5) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.6 (54.7) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

10.3 (50.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.5 (34.7) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −25.0 (−13.0) |

−22.0 (−7.6) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.3 (36.1) |

5.0 (41.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−7.0 (19.4) |

−12.6 (9.3) |

−18.0 (−0.4) |

−25.0 (−13.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 35.4 (1.39) |

38.3 (1.51) |

38.2 (1.50) |

52.0 (2.05) |

56.3 (2.22) |

63.2 (2.49) |

44.7 (1.76) |

43.2 (1.70) |

46.7 (1.84) |

52.4 (2.06) |

57.4 (2.26) |

50.5 (1.99) |

578.3 (22.77) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 14 | 131 |

| Average snowy days | 10 | 9 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 39 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 81 | 75 | 67 | 64 | 65 | 65 | 61 | 60 | 67 | 73 | 79 | 83 | 70 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 73.8 | 100.7 | 151.3 | 176.2 | 230.5 | 274.3 | 316.1 | 294.8 | 209.8 | 153.4 | 87.5 | 55.5 | 2,123.9 |

| Source: Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia[21] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1093 | 3,900 | — |

| 1386 | 5,800 | +0.14% |

| 1800 | 10,564 | +0.14% |

| 1878 | 15,875 | +0.52% |

| 1900 | 27,586 | +2.54% |

| 1905 | 34,110 | +4.34% |

| 1910 | 39,487 | +2.97% |

| 1921 | 48,817 | +1.95% |

| 1948 | 59,504 | +0.74% |

| 1953 | 62,659 | +1.04% |

| 1961 | 65,367 | +0.53% |

| 1971 | 72,208 | +1.00% |

| 1981 | 82,527 | +1.34% |

| 1991 | 86,518 | +0.47% |

| 2002 | 87,288 | +0.08% |

| 2011 | 83,524 | −0.49% |

| There is no citation available for pre-1948 population. Source: [22] | ||

The city population has been expanded by Yugoslav-era settlers and urbanization from its surroundings. Serb refugees of the Yugoslav Wars (1991–95) and the Kosovo War (1998–99), especially during and following the 1999 NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, as well as emigrants from Kosovo in the aftermath of the latter conflict have further increased the population.

According to the 2011 census results, there are 83,524 inhabitants in the city of Vranje.

Ethnic groups

The ethnic composition of the city administrative area (2011 census):[23]

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 76,569 | 91.67% |

| Roma | 4,654 | 5.57% |

| Bulgarians | 589 | 0.71% |

| Macedonians | 255 | 0.31% |

| Montenegrins | 48 | 0.06% |

| Gorani | 43 | 0.05% |

| Croats | 33 | 0.04% |

| Yugoslavs | 22 | 0.03% |

| Muslims | 17 | 0.02% |

| Albanians | 13 | 0.02% |

| Russians | 10 | 0.01% |

| Others | 1,271 | 1.52% |

| Total | 83,524 |

Municipalities and settlements

The city of Vranje consists of two city municipalities: Vranje and Vranjska Banja.[2] Their municipal areas include the following settlements:

- Municipality of Vranje

- Aleksandrovac

- Barbarušince

- Barelić

- Beli Breg

- Bojin Del

- Bresnica

- Buljesovce

- Buštranje

- Crni Lug

- Čestelin

- Ćukovac

- Ćurkovica

- Davidovac

- Dobrejance

- Donja Otulja

- Donje Punoševce

- Donje Trebešinje

- Donje Žapsko

- Donji Neradovac

- Dragobužde

- Drenovac

- Dubnica

- Dulan

- Dupeljevo

- Golemo Selo

- Gornja Otulja

- Gornje Punoševce

- Gornje Trebešinje

- Gornje Žapsko

- Gornji Neradovac

- Gradnja

- Gumerište

- Katun

- Klašnjice

- Koćura

- Kopanjane

- Kruševa Glava

- Krševica

- Kupinince

- Lalince

- Lepčince

- Lukovo

- Margance

- Mečkovac

- Mijakovce

- Mijovce

- Milanovo

- Milivojce

- Moštanica

- Nastavce

- Nova Brezovica

- Oblička Sena

- Ostra Glava

- Pavlovac

- Pljačkovica

- Preobraženje

- Ranutovac

- Rataje

- Ribnice

- Ristovac

- Roždace

- Rusce (Vranje)

- Sikirje

- Smiljević

- Soderce

- Srednji Del

- Stance

- Stara Brezovica

- Strešak

- Stropsko

- Struganica

- Studena

- Surdul

- Suvi Dol

- Tesovište

- Tibužde

- Trstena

- Tumba

- Urmanica

- Uševce

- Viševce

- Vlase (Vranje)

- Vranje

- Vrtogoš

- Zlatokop

- Municipality of Vranjska Banja

Society and culture

Culture

Vranje was an important Ottoman trading site. The White Bridge is a symbol of the city and is called "most ljubavi" (lovers' bridge) after the tale of the forbidden love between the Muslim girl Ajša and Christian Stojan that resulted in the father killing the couple. After that, he built the bridge where he had killed her and had the story inscribed in Ottoman Arabic. The 11th-century Markovo Kale fortress is in the north of the city. The city has traditional Balkan and Ottoman architecture.

The well-known theater play Koštana by Bora Stanković is set in Vranje.

Vranje is famous for its popular, old music, lively and melancholic at the same time. The best known music is from the theater piece with music, Koštana, by Bora Stanković. This original music style has been renewed recently by taking different, specific, and more oriental form, with the contribution of rich brass instruments. It is played particularly by the Vranje Romani people.

Vranje is the seat of Pčinja District and, as such, is a major center for cultural events in the district. Most notable annual events are Borina nedelja, Stari dani, Dani karanfila (in Vranjska Banja), etc.

Vranje lies close to Besna Kobila mountain and Vranjska Banja, locations with high potential that are underdeveloped. Other locations in and around Vranje with some tourist potential include Prohor Pčinjski monastery, Kale-Krševica, Markovo kale, Pržar, birth-house museum of Bora Stankovic.

Largest hotels are Hotel Vranje, near the center and Hotel Pržar overlooking the city and the valley. The city has traditional Serbian cuisine as well as international cuisine restaurants and many cafes and bars.

Culture institutions

- National Museum (in former Pasha's residence, built in 1765)

- Youth Cultural Centre

- National Library

- Centre for Talents

- Theater "Bora Stanković"

- Tourist organization of Vranje

Sport

The city has one top-flight association football team, Dinamo Vranje.

Economy

Vranje is located in southern Serbia, on Corridor X near the border with North Macedonia and Bulgaria. The distance from Thessalonica international harbor is 285 km (177 mi); distance from the international airports of Skopje and Niš are 90 km (56 mi). Vranje has a long tradition of industrial production, trade, and tourism and is rich in natural resources, such as forests and geothermal resources.[24]

Until the second half of the 20th century Vranje was a craftsman town. The crafts included weaving, water-milling, and carriages craft. With the beginning of industrialization in the 1960s, many of these crafts disappeared. In those years, many factories were opened, such as the Tobacco Industry of Vranje (Serbian: Дуванска индустрија Врање), Simpo, Koštana (shoe factory), Yumco (cotton plant), Alfa Plam (technical goods), SZP Zavarivač Vranje and others.

The most common industries in the city of Vranje are timber industry, clothing, footwear and furniture, food and beverages, agricultural, textile industry, chemical industry, construction industry, machinery and equipment, and business services. There are more than 2,500 small- and medium-size companies. To potential investors there are industrial sites, with plan documents and furnished infrastructure. Among the companies with business locations in the city are British American Tobacco, Simpo, Sanch, Kenda Farben, Danny style, OMV and Hellenic Petroleum.[24]

As of September 2017, Vranje has one of 14 free economic zones established in Serbia.[25]

- Historical statistics

As of 1961, there were 1,525 employees; in 1971, there were 4,374 employees; and in 1998, there were 32,758 employees. Following the breakup of Yugoslavia, and due to sanctions imposed on FR Yugoslavia during the rule of Slobodan Milošević, the number of employees began to drop; factories which employed a large number of people closed, among whom are Yumco and Koštana. As of 2010, there were only 18,958 employed inhabitants and 7,559 unemployed. As of 2010, the city of Vranje has 59,278 available workers. In 2010, the City Council passed the "Strategy of sustainable development of the city of Vranje from 2010 to 2019," for the achievement of objectives through a transparent and responsible business partnership with industry and the public.[24]

- Economic preview

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[26]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 185 |

| Mining and quarrying | 312 |

| Manufacturing | 8,085 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 190 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 424 |

| Construction | 564 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 3,037 |

| Transportation and storage | 987 |

| Accommodation and food services | 658 |

| Information and communication | 206 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 289 |

| Real estate activities | 4 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 618 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 353 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 1,529 |

| Education | 1,431 |

| Human health and social work activities | 2,016 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 255 |

| Other service activities | 347 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 103 |

| Total | 21,594 |

Notable people

- Borisav (Bora) Stanković (1875–1927), a Serbian writer.

- Miroslav-Cera Mihailović, contemporary poet.

- Jovan Hadži-Vasiljević, (1866–1946), historian.

- Djordje Tasić, (1892–1943), one of the most notable Serbian jurists.

- Justin Popović (1894–1979), theologian and philosopher.

- Gedik Ahmed Pasha († 482), Grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire

- Physicians: Dr. Franjo Kopsa († 1898); Dr. Dragoljub Mihajlović († 1980).

- Scientists: Dejan Stojković (Ph.D. physics, professor in USA), Marjan Bosković (MD), anatomy professor; Dragan Pavlovć (MD), professor of pathophysiology and anesthesiology; Dragoslav Mitrinović, mathematician.

- Painters: Jovica Dejanović, Miodrag Stanković-Dagi, Zoran Petrušijević-Zop, Suzana Stojanović.

- Musicians: Bakija Bakić († 1989), Staniša Stošić († 2008), Čedomir Marković

- Aleksandar Davinić: journalist, satirist.

- Curators: Jelena Veljković, Marko Stamenković.

- Architects: Milan Stamenković (Moscow Architectural Institute State Academy)

- Josip Kuže, was a Yugoslav and Croatian football coach and former player.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

The city of Vranje is twinned with:

See also

References

- "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- "UNESCO designates 66 new Creative Cities | Creative Cities Network". en.unesco.org. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- "Vranje među kreativnim gradovima Uneska". www.novosti.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Janković, Đorđe. "The Slavs in the 6th century North Illyricum". Projekat Rastko (in Serbian). Belgrade. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Bazić 2008, p. 254.

- Blagojević 2001, p. 26.

- Синиша Мишић (2010). Лексикон градова и тргова средњовековних српских земаља: према писаним изворима. Завод за уџбенике. p. 76. ISBN 978-86-17-16604-3.

- Starinar 1936, p. 72: "... сродника и наследника кнеза Балдовина. Кнез Балдовин je из времена краља Стефана Уроша III Дечанског (1321 — 1331). Пре њега je, изгледа, био y Врањи тепчија Кузма, a пре овога казнац Мирослав (свакако онај исти који ce помиње y ..."

- Blagojević 2001, pp. 41, 52.

- Blagojević 2001, p. 252.

- Reise von Belgrad nach Salonik. Von J. G. v. Hahn, K. K. Consul für östliche Griechenland. Wien 1861

- von Hahn, Johann. Bulgarians in Southwest Morava, Illuminated by A. Teodoroff-Balan

- Jagodić, Miloš (1998). "The Emigration of Muslims from the New Serbian Regions 1877/1878". Balkanologie. 2 (2).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) para. 6. "According to the information about the language spoken among the Muslims in the cities, we can see of which nationality they were. So, the Muslim population of Niš and Pirot consisted mostly of Turks; in Vranje and Leskovac they were Turks and Albanians"; para. 11. "The Turks have been mostly city dwellers. It is certain, however, that part of them was of Albanian origin, because of the well-known fact that the Albanians have been very easily assimilated with Turks in the cities."; para. 26, 48.

- in “Vranje through centuries” (“Vranje kroz vekove”, Vranje 1993)

- see Aleksandar Trajkovic : INOGOSTE - Zupa u Juznoj Srbiji, Dom Kulture Radoje Domanovic, Surdulica, 2ooo)

- I. Jovanovic: Tefters and lists, population of Vranje in the 19th century; in Serbian: Ivan Jovanovic, Tefteri I spiskovi, stanovnistvo Vranja u devetnaestom veku, Istorijski arhiv “31. Januar3, 2009, Vranje)

- Malcolm, Noel (1998). Kosovo: A short history. London: Macmillan. p. 208. ISBN 9780333666128.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)"Vranje itself became a major Gypsy centre, with a large population of Serbian-speaking Muslim Gypsies. After the nineteenth- century expulsions of Muslim Slavs and Muslim Albanians from the Serbian state, these Gypsies were virtually the only Muslims permitted to remain on Serbian soil: in 1910 there were 14,335 Muslims in the whole kingdom of Serbia (6,089 of them in Vranje), and roughly 90 per cent of the urban Muslims were Gypsies."

- Bazić 2008, p. 255.

- Mitrović 2007, pp. 222–223.

- "Monthly and annual means, maximum and minimum values of meteorological elements for the period 1981–2010" (in Serbian). Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. Retrieved 25 February 2017.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Агенција за страна улагања и промоцију извоза Републике Србије (СИЕПА) – Град Врање

- Mikavica, A. (3 September 2017). "Slobodne zone mamac za investitore". politika.rs (in Serbian). Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- "Miasta partnerskie i zaprzyjaźnione Nowego Sącza". Urząd Miasta Nowego Sącza (in Polish). Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2013.

Sources

- Blagojević, Miloš (2001). Државна управа у српским средњовековним земљама [State administration in the Serb medieval lands]. Službeni list SRJ.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitrović, Andrej (2007). Serbia's Great War, 1914–1918. West Lafayette, Indiana: Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-477-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pešić, Miodrag (1975). Врање. Нова Југославија.

- Врање кроз векове, избор радова. Vranje. 1993.

- Dragoljub Mihajlović (1969). Vranje koje ne umire. Izdanje autora.

- Simonović, Rista (1964). Врање, околина и људи. 1.

- Simonović, Rista (1973). Врање, околина и људи. 2.

- Simonović, Rista (1984). Staro vranje koje nestaje. I.

- Врањски гласник: библиографија. 1998.

- Борислава Лилић (2006). Југоисточна Србија, 1878-1918. Институт за Савремену Историју.

- Bulatović, Aleksandar (2007). Врање: Културна стратиграфија праисторијских локалитета у Врањској регији. Archaeological institute, Belgrade; National museum, Vranje.

- Trifunoski, Jovan (1963). Врањска котлина.

- Nikolić, Rista. Врањска Пчиња.

- Mišić, Siniša (2002). Југоисточна Србија средњег века. Vranje: Međuopštinski arhiv Vranje i Udruženje istoričara Braničeva i Timočke krajine.

Further reading

- Tatomir P. Vukanović (1978). Vranje: etnička istorija i kulturna baština vranjskog gravitacionog područja u doba oslobođenja od Turaka, 1878. Radnički univerzitet u Vranju.

- Сања Златановић (2003). Свадба - прича о идентитету: Врање и околина. Etnografski institut SANU. ISBN 978-86-7587-026-5.

- Jadranka Đorđević (2001). Srodnički odnosi u Vranju. Etnografski institut. ISBN 978-86-7587-018-0.

- Hrabri vranjski i moravski bataljoni: 1912-1918. Vranjska podružnica Udruženja nosilaca Albanske spomenice. 1970.

- Bazić, Mirjana (2008). "Istorijski značaj i prosvetna politika grada Vranja" (PDF). Baština. 24: 253–260.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vranje. |