Vračar

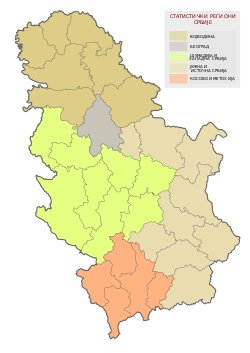

Vračar (Serbian Cyrillic: Врачар, pronounced [v̞rǎt͡ʃaːr]) is a municipality of the city of Belgrade. According to the 2011 census results, the municipality has a population of 56,333 inhabitants.

Vračar Врачар | |

|---|---|

Cathedral of Saint Sava in mid-August 2008 | |

Flag .png) Coat of arms | |

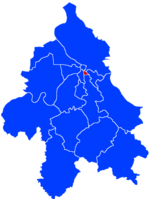

Location of Vračar within the city of Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44.7953°N 20.4678°E | |

| Country | |

| City | |

| Status | Municipality |

| Settlements | 1 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Municipality of Belgrade |

| • Mun. president | Milan Nedeljković (SNS) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 2.87 km2 (1.11 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 142 m (466 ft) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 56,363 |

| • Density | 20,000/km2 (51,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11000 |

| Area code(s) | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

| Website | www |

With an area of only 291 hectares, it is the smallest of all Belgrade's (and Serbian) municipalities, but also the most densely populated. Vračar is one of the three municipalities that constitute the very center area of Belgrade, together with Savski Venac and Stari Grad. It is an affluent municipality, having one of the most expensive real estate prices within Belgrade, and has the highest proportion of university educated inhabitants compared to all other Serbian municipalities.[2] One of the most famous landmarks in Belgrade, the Saint Sava Temple is located in Vračar.

Vračar borders five other Belgrade municipalities: Voždovac to the south, Zvezdara to the east, Palilula to the northeast, Stari Grad to the north and Savski Venac to the west. It is generally bounded by the three boulevards: Boulevard of Liberation, Southern Boulevard and the Boulevard of King Aleksandar.

Though today the smallest municipality of Belgrade, historically Vračar occupied much larger territory. It was divided in three parts: East Vračar, which roughly occupies the modern municipality, West Vračar which is today a local community (sub-municipal unit) within the municipality of Savski Venac and Great Vračar, which is today known as Zvezdara, though the local community of Vračarsko Polje (Vračar Field) retained its name within the Zvezdara municipality.[3]

Geography

The neighborhood of Vračar is located on the top of the Vračar plateau, partially in the easternmost section of the municipality of Savski Venac as a result of a series of administrative changes of municipal boundaries after World War II. Despite its small area, being located less than a kilometer away from downtown (Terazije) it borders many other Belgrade neighborhoods: the square and neighborhood of Slavija to the north, Palilula to the northeast, Čubura and Gradić Pejton to the east, Neimar to the south and the park and neighborhood of Karađorđev Park to the southwest.

With 132 metres (433 feet), Vračar plateau is one of the highest points in downtown Belgrade, which is generally built on a hilly terrain (32 hills altogether).[4] The top of the hill was flattened and turned into the plateau when earth from the top was used to cover and drain the pond on Slavija, in the western foothills of the Vračar hill.[5] Almost no geographical features survive today as the area is completely urbanized, except for the small section of Karađorđev Park on the southern slopes of the plateau. Some much larger parks, like major portion of Karađorđev Park or parks Manjež and Tašmajdan are left just outside the Vračar's administrative borders.

Cityscape

The most dominant feature of modern Vračar is the massive Temple of Saint Sava. Its decades long, troubled construction shaped not only the present appearance of the plateau but also the entire skyline of Belgrade. The plateau has been reshaped in the early 2000s, with fountains, marble access roads to the temple with pillars, and playgrounds added, while the already existing monument to the leader of the First Serbian Uprising, Karađorđe, was erected on a low, artificial hillock. The plateau is also the location of the National Library of Serbia and Karađorđev Park begins here, with the craftsmen settlement of Gradić Pejton and the bohemian quarter of Čubura nearby.

History

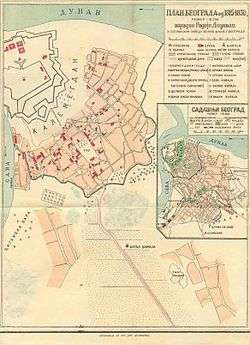

Vračar (derived from Serbian word vrač meaning the 'medicine man', 'healer') was first mentioned in 1440, during the siege of Belgrade by the Ottoman sultan Murad II. Ottoman map from 1492 mentions Vračar as a tower.[3] In 1560 it is mentioned as the Christian village outside the fortress of Kalemegdan with 17 houses. It is believed this village is the place where in 1595 the Turkish grand vizier Sinan Pasha burned at the stake the remains of Saint Sava, a major Serbian saint, to pacify and punish a rebellious population.

At the beginning of the 19th century Vračar, as a geographical term, referred to a much wider area, from the village of Savamala (present Mostar) on the west to the village of Paliula (present neighborhood of Karaburma), which means it used to cover at least three times larger territory than the municipality covers today. By order of prince Miloš Obrenović, an alternative city centre with western characteristics was designed and built here while city of Belgrade was still under Turkish rule and for three quarters an oriental town with all the characteristics of Islamic architecture. On the other hand, Vračar was built with broad streets and boulevards, first parks and monuments. It was housing all Serbian public buildings and state institutions in Belgrade, known as a place where the remains of the Serbian Saint Archbishop Sava Nemanjic were burned by Turks. The Masonic Temple on this site was destroyed during the German bombing of Belgrade on 6 April 1941. Today, it is the site of the biggest Christian Orthodox Cathedral in the world.

The Times on October 17, 1843 published a text full of exultations. 'Four years have passed since the time when I was last here, and how Belgrade has changed! I have hardly recognised it. The high belfry on the church (Cathedral) now screens by its shadow the Turkish mosques; many shops are now provided with new doors and glass windows, oriental clothing is more rare and houses with several storeys, in European manner, are being built everywhere'.

Many architects-baumeisters (builders) Germans, Czechs, Italians and the Serbians who appeared only at the end of the 1860s built new Serbian Belgrade in Vračar. After 1867, when Turkish military garrisons left the Belgrade fortress Kalemegdan they extended their architectural activities on the ruins of the Turkish houses (Stambol gate, Dorćol, Palilula) and on the ruins of the Serbian huts in the Sava river port, Savamala.

When Belgrade was divided into six quarters in 1860, Vračar was one of them.[6] By the census of 1883 it had a population of 5,965.[7]

In the eastern section of Vračar, on the border of the Kalenić, Čubura and Krunski Venac neighborhoods, a settlement of one-floor villas began to develop in the early 1920s. At that time, a tram line No. 1-a was passing through here, connecting downtown to Crveni Krst. As majority of the parcels were purchased by the army generals and their family members, the neighborhood became known as the "Quarter of the Generals" (Milivoje Zečević, Bogoljub Ilić, Svetislav Milosavljević, families Kocić, Lukić, Petrović, Đonović, etc.). The villas were later upgraded with additional floors and were given names (Villa Stana, Villa Kocić, Villa Ilić).[8]

Since the 1880s, the neighborhood was roughly divided into Zapadni Vračar (West Vračar) and Istočni Vračar (East Vračar), divided by the road of Šumadijski put (present Boulevard of Liberation). The municipality of Vračar was officially formed in 1952 after Belgrade was administratively reorganized from districts (rejon) to municipalities. Already on September 1, 1955 Vračar was divided into Zapadni Vračar (West Vračar) and Istočni Vračar (East Vračar). Year and a half later, on January 1, 1957, parts of Istočni Vračar merged with the municipality of Neimar and the western part of the municipality of Terazije to create new, albeit the smallest municipality in Belgrade, Vračar. Zapadni Vračar became municipality of Savski Venac, while the easternmost section of Istočni Vračar became part of the municipality of Zvezdara (local community of Vračarsko Polje; Zvezdara hill itself was styled Veliki Vračar - Big Vračar).

Neighborhoods

As Vračar has a very small area by itself, its sub-neighborhoods are also small, some of them encompassing only a street or so:

|

|

|

|

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 62,158 | — |

| 1953 | 75,139 | +3.87% |

| 1961 | 88,422 | +2.06% |

| 1971 | 84,291 | −0.48% |

| 1981 | 78,862 | −0.66% |

| 1991 | 69,680 | −1.23% |

| 2002 | 58,386 | −1.59% |

| 2011 | 56,333 | −0.40% |

| Source: [9] | ||

As the other two central Belgrade municipalities, Stari Grad and Savski Venac, Vračar has been depopulating for the last five decades. Despite that, Vračar is by far, thanks to its small area, the most densely populated municipality of Belgrade, with 18,967 inhabitants per square kilometer (2011 census; 28,380 back in 1971).

Administration

Recent presidents of the municipal assembly:

- 1993–1996: Dragan Maršićanin (b. 1950)

- 1996–2006: Milena Marković (b. 1950)

- 2006–2015: Branimir Kuzmanović (b. 1968)

- 2015–2016: Tijana Blagojević (b. 1980)

- 2016–present: Milan Nedeljković (b. 1957)

Mrs Dunja Vlahović (b. 1912), who was municipal president from January 1957 when Vračar was restored as one municipality, was one of the first female municipal presidents in Serbia.

District (Serbian: srez) which comprised the suburban area of Belgrade after 1945 was called Vračar District (Vračarski srez) though the name Belgrade District was also used. In 1955 the Vračar District merged with the City of Belgrade and parts of some bordering districts to create new, enlarged Belgrade District.

Economy

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[11]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 109 |

| Mining and quarrying | 53 |

| Manufacturing | 1,840 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 1,084 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 416 |

| Construction | 2,027 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 5,747 |

| Transportation and storage | 1,191 |

| Accommodation and food services | 2,320 |

| Information and communication | 2,099 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 1,031 |

| Real estate activities | 351 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 4,608 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 5,510 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 2,338 |

| Education | 1,678 |

| Human health and social work activities | 2,413 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 1,373 |

| Other service activities | 1,979 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 8 |

| Total | 38,175 |

Characteristics

Vračar is a residential and very important commercial part of Belgrade. The tall skyscraper in downtown Belgrade, the Beograđanka, Cvetni Trg (famous for its flower shops) and the square of Slavija occupy the western section of the municipality. Other important features are the Temple of Saint Sava and the National Library of Serbia on the Vračar plateau, northern section of the big interchange Autokomanda and the stadium of the FK Obilić (Miloš Obilić Stadium) and the Architecture high school in the extreme west of the municipality. Commercial center of the municipality is the area surrounding the Kalenić, largest open green market in Belgrade.

The "Vračar plane tree" is a tree in the Makenzijeva street, protected as the natural monument. It is a London plane, 23 m (75 ft) high in 2013 and is estimated to be planted circa 1860.[12]

International cooperation

Vračar is twinned with following cities and municipalities:[13]

See also

- Istočni Vračar

- Zapadni Vračar

- Veliki Vračar

- Subdivisions of Belgrade

- List of Belgrade neighborhoods and suburbs

Historical references

- Beograd - Izdanje opštine beogradske, 1911;

- Zapisi starog Beograđanina 2000;

- Iz starog Beograda, Živorad P. Jovanović 1964;

- Siluete starog Beograda, Milan Jovanović - Stojimirović, 1971;

- Uspon Beograda, Milivoje M.Kostić, 2000;

- Beogradske gradske pijace, JKP Beogradske pijace, 1999;

- Vračarski glasnik, 1997–2004

References

- "Насеља општине Врачар" (pdf). stat.gov.rs (in Serbian). Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Retrieved on 2013-02-01.

- Marija Brakočević (21 May 2014). "Beograd leži na 23 brda" [Belgrade lays on 23 hills]. Politika (in Serbian).

- "Opservatorija: Beograd - Vračar (osnovana 1887 godine)" (in Serbian). Politika. 2017.

- Milan Četnik, "Generali na koti Vračar", Politika (in Serbian)

- Dejan Aleksić (9 May 2017), "Šest decenija opštine Palilula - Nekad selo, a danas urbana celina grada", Politika (in Serbian)

- Belgrade by the 1883 census

- Nenad Novak Stefanović (9 November 2018). "Кад је трамвај звонио Врачаром" [When tram was ringing through Vračar]. Politika-Moja kuća (in Serbian). p. 01.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved 26 February 2017.

- "ETHNICITY Data by municipalities and cities" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 1 March 2018.

- "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- Vladimir Vukasović (9 June 2013), "Prestonica dobija još devet prirodnih dobara", Politika (in Serbian)

- Stalna konferencija gradova i opština. Retrieved on 2007-06-18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vračar. |