Kladovo

Kladovo (Serbian Cyrillic: Кладово, pronounced [klâdɔʋɔ]) is a town and municipality located in the Bor District of eastern Serbia. It is situated on the right bank of the Danube river. The population of the town is 8,913, while the population of the municipality is 20,635 (2011 census).

Kladovo Кладово | |

|---|---|

Town and municipality | |

Kladovo town panorama | |

Coat of arms | |

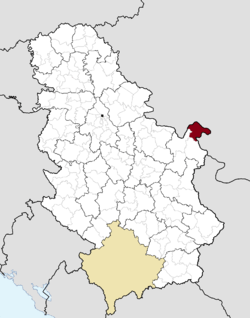

Location of the municipality of Kladovo within Serbia | |

| Coordinates: 44°37′N 22°37′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Southern and Eastern Serbia |

| District | Bor |

| Settlements | 23 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Saša Nikolić |

| Area | |

| • Town | 29.13 km2 (11.25 sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 627.25 km2 (242.18 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 45 m (148 ft) |

| Population (2011 census)[2] | |

| • Town | 8,913 |

| • Town density | 310/km2 (790/sq mi) |

| • Municipality | 20,635 |

| • Municipality density | 33/km2 (85/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 19320 |

| Area code | +381(0)19 |

| Car plates | KL |

| Website | www |

Name

In Serbian, the town is known as Kladovo (Кладово), in Romanian Cladova, in German as Kladowo or Kladovo and in Latin and Romanised Greek as Zanes. In the time of the Roman Empire, the name of the town was Zanes while the fortifications was known as Diana and Pontes (from Greek "sea" -pontos, or Roman "bridge" - pontem). Emperor Trajan had a number of fortications constructed in the area during the Roman times, such as the well-known Trajan's Bridge (Pontes was built on the Serbian side, Theodora was built on the Romanian side). Later, Slavs founded a settlement that was named Novi Grad (Нови Град), while Ottomans built a fortress here and called it Fethülislam. The present-day name of Kladovo is first recorded in 1596 in an Austrian military document.

There are several theories about the origin of the current name of the town:

- According to one theory (Ranka Kuic), name of the town derived from Celtic word "kladiff" meaning "cemetery" in English.

- According to another theory (Ranko Jakovljevic), the name derived from the word "klad" (a device used to hold a person shackled).

- A third theory has it that the name derives from the Slavic word "kladenac" meaning "a well" in English or from the Slavic word "klada" meaning "(tree) stump".

- There is also a theory that the name goes back to the Bulgarian duke Glad, who ruled over this region in the 9th century.

There is a settlement with the same name in Russia near Moscow and it is believed that this settlement was founded by Serbs who moved there from Serbian Kladovo in the 18th century. One of the suburbs of Berlin also has this name, which originates from the Slavic Lusatian Serbs (Sorbs) who live in eastern Germany.

The name is also found in the Arad and Timiș counties of Romania, Cladova, in Arad county Cladova, Arad, Cladova in Timiș county Cladova, Timiș

Geography

East of the town are the sandy region of Kladovski Peščar, black locust forests and a marshy area of Kladovski Rit which used to be a large fish pond. It is home for 140 species of birds, of which 80 are nesting in the area. There are mixed colonies of pygmy cormorants and herons, while other birds include swans, white-tailed eagles, European bee-eaters, numerous ducks, etc. Surrounding area is a hunting ground for wild boars. Neighboring geographical localities, like Osojna and Lolićeva Česma, are popular local excursion areas.[3]

History

Early Bronze Age pottery of the Kostolac-Kocofeni culture was found in Donje Butorke, Kladovo,[4] as well as several miniature duck-shaped vases of 14th century BC in Mala Vrbica and Korbovo.[5] Bronze Age necropolis with rituals, pottery (decorated with meander) and other significant archaeological items were found in Korbovo.[6][7]

In ancient times, a fortification near Trajan's bridge named Zanes/Pontes existed at this location, the area was governed by the Dacian Albocense tribe. In the Middle Ages, the Slavs founded here new town named Novi Grad (Нови Град), but it was razed by the Hungarians in 1502. It was rebuilt in 1524 by the Ottomans and received new name: Fethi Islam (Fethülislam). According to Ottoman traveler, Evliya Chelebi, who visited the town in 1666, most of its inhabitants spoke local Slavic language and Turkish language, while some also spoke Vlach. In 1784, the population of Kladovo numbered 140 Muslim and 50 Christian houses.

From 1929 to 1941, Kladovo was part of the Morava Banovina of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Settlements

Aside from the town of Kladovo, the municipality includes the following settlements:

- Towns

- Kladovo

- Brza Palanka

- Villages

- Vajuga

- Velesnica

- Velika Vrbica

- Velika Kamenica

- Grabovica

- Davidovac

- Kladušnica

- Korbovo

- Kostol

- Kupuzište

- Ljubičevac

- Mala Vrbica

- Manastirica

- Milutinovac

- Novi Sip

- Petrovo Selo

- Podvrška

- Reka

- Rečica

- Rtkovo

- Tekija na Dunavu

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1948 | 26,161 | — |

| 1953 | 27,792 | +1.22% |

| 1961 | 28,217 | +0.19% |

| 1971 | 33,173 | +1.63% |

| 1981 | 33,376 | +0.06% |

| 1991 | 31,881 | −0.46% |

| 2002 | 23,613 | −2.69% |

| 2011 | 20,635 | −1.49% |

| Source: [8] | ||

According to the 2011 census results, the municipality has a population of 20,635 inhabitants.

Ethnic groups

The ethnic composition of the municipality:[9]

| Ethnic group | Population | % |

|---|---|---|

| Serbs | 17,673 | 85.65% |

| Vlachs | 788 | 3.82% |

| Montenegrins | 236 | 1.14% |

| Romanians | 156 | 0.76% |

| Macedonians | 42 | 0.20% |

| Romani | 36 | 0.17% |

| Croats | 35 | 0.17% |

| Yugoslavs | 16 | 0.08% |

| Others | 1,653 | 8.01% |

| Total | 20,635 |

Economy

The main business are the hydro-electric power plants of Đerdap: Iron Gate I and Iron Gate II. Other businesses began primarily to support the building and operation of the power plant, and the local folk.

The population of the villages around Kladovo is mostly supported by the family members who work as guest-workers in the countries of western Europe, agriculture is a side activity more than an income-generating one.

The following table gives a preview of total number of registered people employed in legal entities per their core activity (as of 2018):[10]

| Activity | Total |

|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry and fishing | 63 |

| Mining and quarrying | 5 |

| Manufacturing | 1,302 |

| Electricity, gas, steam and air conditioning supply | 443 |

| Water supply; sewerage, waste management and remediation activities | 71 |

| Construction | 73 |

| Wholesale and retail trade, repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles | 809 |

| Transportation and storage | 129 |

| Accommodation and food services | 305 |

| Information and communication | 77 |

| Financial and insurance activities | 33 |

| Real estate activities | 2 |

| Professional, scientific and technical activities | 82 |

| Administrative and support service activities | 98 |

| Public administration and defense; compulsory social security | 252 |

| Education | 290 |

| Human health and social work activities | 460 |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | 30 |

| Other service activities | 68 |

| Individual agricultural workers | 139 |

| Total | 4,731 |

Features

Kladovo has one hospital, two daycare and kindergarten centers, one elementary school (grades 1 through 8), one high school and several vocational schools.

Though the river Danube is very polluted by international standards, many people still fish in it. Before the power plant was built, sturgeon caviar from this area was very popular and was exported as a delicacy to the western Europe and the United States. In the 1960s, up to 3 tons of caviar yearly was exported from Kladovo. Record catch from that period is a 188 kg (414 lb) heavy sturgeon with 20 kg (44 lb) of the roe in it. However, the records from the past, dated in 1793, report of the sturgeon which had 500 kg (1,100 lb). The specificity of the Caviar of Kladovo was that the roe gets "ripe" enough during the 850 km (530 mi) long journey of the fish from the Black Sea upstream the Danube. Also, roe was turned into the caviar using the dry method.[11]

The nearby archeological sites include the remnants of Roman Emperor Trajan's bridge, one of many Trajan's tables, remnants of Trajan's road through the Danube's Iron Gates, and the Roman fortress Diana.

The Trajan's Bridge is located 5 km downstream from Kladovo. It had 20 pillars and was 1,200 m long. Trajan's successor Hadrian partially demolished it to prevent the raids of the Dacians and the bridge was later neglected. The bridge is depicted in a relief on the Trajan's Column in Rome. Until the 16th century, it was the largest bridge ever built.[12] The 20 pillars were still visible in 1856, when the level of the Danube hit a record low. In 1906, the Commission of the Danube decided to destroy two of the pillars that were obstructing navigation. In 1932, there were 16 pillars remaining underwater, but in 1982 only 12 were mapped by archaeologists; the other four had probably been swept away by water. Only the entrance pillars are now visible on either bank of the Danube.[13]

When the artificial Đerdap Lake was formed from 1967-72 as a result of the Iron Gate I Hydroelectric Power Station. The lake inundated the old Roman road along the coast and the only remaining part of the old path is the Tabula Traiana, a Roman memorial plaque, which was elevated for 25 m. The process of lifting the table (4 m x 1.75 m) lasted from 1966 to 1969, today is several meters above the lake level and is observable only from the lake.[12]

Remains of the fortress Diana are located 2 km downstream of the Iron Gate I. Diana is one of the largest and best preserved Roman forts on this section of the Danubian Limes. It was built by the emperor Trajan at the beginning of the 2nd century BC and was destroyed by the joint attack of the Slavs and Pannonian Avars in the 6th century.[12]

During the Ottoman occupation of the Balkan peninsula a fortress was built near the town. It was named Fetislam (originally Feht-ul-Islam meaning "gate of Islam") and it is located 300 m (980 ft) upstream of Kladovo's downtown. Construction began in 1524 and the present look of Fetislam dates from the period of Suleiman the Magnificent in the mid 16th century. The construction was supervised by Malkoçoğlu Balı Bey, while the architect was Osman Pasha. It consists of "Big Town" and "Little Town", which represent two levels of the fortress' defense. It was very important for the Ottomans as, due to its location, domineered the Iron Gate gorge. Fetislam has round, two-storeys high towers. The rectangular cannon fortification with six round bastions, Fetislam became important military structure up to the end of World War I. It was damaged in World War II and by the neglect after the war. In 1968 conversion into the sport complex slowly began and it was partially renovated in 1973, including the amphitheater. The fortress was endangered with the rise of the Danube water level with the construction of the massive Iron Gate dam. Today, it contains children's playgrounds, track and soccer fields, handball, volleyball and tennis courts.[12][14]

The Đerdap national park offers scenic views, excellent hunting grounds, and many trails for hiking (most trails are not well marked or maintained, so hiking is recommended only for the experienced).

The town has two hotels: "Đerdap" and "Aquastar Danube". Nearby the city (8 km on the road to Belgrade) there is a youth camp named "Karataš" (Turkish kara-tash for "black stone") which can host some of the visiting tourists. Kladovo has many cafés and restaurants, some offering live music entertainment late into the night. The town's quay stretches about 3 kilometers (1.9 mi) along the Danube river and is used for walking and cycling.

Kladovo has a beach, Đerdap Archaeology Museum, Orthodox Church of Saint George and a pedestrian zone (Kladovo Skadarlija). Kladovo is on the European bicycle path and in 2016 about 16,000 cyclists passed through the town. As of 2017, the bus line Belgrade-Kladovo was the only one in Serbia which had bicycle carriers on the buses. The neighboring villages of Tekija and Brza Palanka also arranged beaches on the river. Other touristic attractions include the organized visits to the Iron Gate I power plant, local cuisine and the surrounding wine region between Kladovo and Negotin, the Negotin Valley. In the 19th century, the wine produced here was shipped to Belgrade, Novi Sad, Budapest, Vienna, etc.[12]

The public market was open in 1586, when the Ottomans moved the seat of nahiyah to Fetislam tower. In the mid-19th century, it was recorded that the market is open on Saturdays. In the mid-20th century, the market was equipped with the concrete market stalls, receiving little maintenance[15] until 2019, when more extensive renovation works begun.[16]

Gallery

2.jpg) Tabula Traiana

Tabula Traiana Fetislam Fortress entry

Fetislam Fortress entry

Sports Hall "Jezero"

Sports Hall "Jezero"

Notable residents

Born in Kladovo municipality:

- Avram Petronijević, born in Tekija (Kladovo)

- Darko Perić, actor, born in Kladovo

Temporary residents:

- Saint Nicodim Tismansky (14-15th century)

- Vuk Stefanović Karadžić, a Serbian linguist and reformer of the Serbian language[17]

See also

References

- "Municipalities of Serbia, 2006". Statistical Office of Serbia. Retrieved 28 November 2010.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia: Comparative Overview of the Number of Population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011, Data by settlements" (PDF). Statistical Office of Republic Of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4. Retrieved 27 June 2014.

- Slobodan T. Petrović (18 March 2018). "Стубови Трајановог моста" [Pillars of the Trajan's Bridge]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1068 (in Serbian). pp. 22–23.

- "[Projekat Rastko] Dragoslav Srejovic: Kulture bakarnog i ranog bronzanog doba na tlu Srbije". www.rastko.rs. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- http://sehumed.uv.es/revista/numero16/SEHUMED_colecc131.PDF

- "[Projekat Rastko] Dr Draga Garasanin: Bronze Age in Serbia". www.rastko.rs. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Страница није пронађена « Народни музеј у Београду Archived 2011-10-06 at the Wayback Machine

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "2011 Census of Population, Households and Dwellings in the Republic of Serbia" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "MUNICIPALITIES AND REGIONS OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA, 2019" (PDF). stat.gov.rs. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. 25 December 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- Miroslav Stefanović (22 April 2018). "Мегдани аласа и риба грдосија" [Fights between the fishermen and the giant fishes]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1073 (in Serbian). pp. 28–29.

- Olivera Milošević (3 September 2017), "Dunav i istorija magneti Kladova", Politika (in Serbian), p. 16

- Romans Rise from the Waters Archived 2006-12-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Mirjana Nikić (21 December 2018). "Игралиште одржало тврђаву" [Playground kept the fortress in shape]. Politika-Moja kuća (in Serbian). p. 01.

- U.R. (12 September 2018). "Неуређена кладовска пијаца" [Unregulated Kladovo market]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 13.

- "Počeli radovi na rekonstrukciji gradske zelene pijace". Municipality of Kladovo official website (in Serbian). 14 February 2019.

- Stojanovic, Milija (11 June 2017). "DA LI ZNATE DA JE VUK KARADŽIĆ U KLADOVU I NEGOTINU PROVEO NAJLEPŠE GODINE SVOG ŽIVOTA". TK Magazin (in Serbian). Retrieved 19 July 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kladovo. |

- Official website

- Library Cultural Center Kladovo (in Serbian)