Persoonia

Persoonia is a genus of about one hundred species of shrubs and small trees in the subfamily Persoonioideae in the large and diverse plant family Proteaceae. In the eastern states of Australia, they are commonly known as geebungs, while in Western Australia and South Australia they go by the common name snottygobbles.[1] While their flowers are small and not prominent, persoonias are best known in the Australian bush for the striking bright green foliage of many species.

| Persoonia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Persoonia levis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Subfamily: | Persoonioideae |

| Tribe: | Persoonieae |

| Genus: | Persoonia Sm. |

| Type species | |

| Persoonia lanceolata | |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

| |

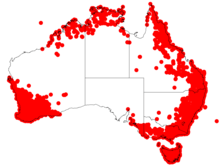

| Occurrence data downloaded from AVH | |

Description

Persoonias are usually shrubs, sometimes small trees and usually have smooth bark. The adult leaves are simple, usually arranged alternately but sometimes in opposite pairs, or in whorls of three or four. If a petiole is present, it is short. The flowers are arranged singly or in racemes, usually of a few flowers, either in leaf axils or on the ends of the branches. Sometimes the raceme continues to grow into a leafy shoot. The tepals are free from each other except near their base, have their tips rolled back and are usually yellow. There is a single stigma on top of the ovary and surrounded by four stamens. The fruit is a drupe containing one or two seeds.[2][3][4]

Taxonomy and naming

The genus Persoonia was first formally described in 1798 by James Edward Smith and the description was published in Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.[5][6] The generic name is in honour of Dutch mycologist and botanist Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.[4] Smith did not nominate a type species but in 1988, Persoonia lanceolata was nominated as the lectotype.[7]

The term geebung is derived from the Dharug language word geebung, while the Wiradjuri term was jibbong.[8] The etymology of "snottygobble" is more obscure. The English Dialect Dictionary published in 1904 lists snotergob, snot-gob and snotty-gobble as "the fruit of the yew-tree, Taxus baccata" noting that "children devour quantities of the red part of these berries, which they call snotty-gobbles, and suffer no ill-effects".[9] The pulp around the hard stone in the drupes of Persoonia is edible although "the operation is a little like nibbling sweet cotton wool".[10]

Molecular hylogenetic studies indicate that Toronia, Garnieria and Acidonia all lie within the large genus Persoonia.[11]

Distribution and habitat

All species are endemic to Australia, though a closely related species, Toronia toru is found in New Zealand and has been described as a species within the genus Persoonia previously. They are widespread in non-arid regions. One species, P. pertinax, is found only in the Great Victoria Desert, while a few other species venture into the arid zone, but most are concentrated in the subtropical to temperate parts of south eastern and south western Australia, including Tasmania.

Most species are plants of well-drained, acid, sandy or sandstone-based soils that are low in nutrients, although one, Persoonia graminea, grows in swampy habitats. Three species (P. acicularis, P. bowgada and P. hexagona) tolerate mildly calcareous soils, and several south eastern species sometimes grow on basalt-derived soils, and but these are unusual. The greatest diversity of species is found in areas with soils derived from sandstones and granites.

Ecology

Interactions between micro-organisms and Persoonia species are poorly known, and no mycorrhizal associations have been reported for any species of Persoonioideae. Several species of Persoonia (P. elliptica, P. gunnii, P. longifolia, P. micranthera, P. muelleri) are known to be highly susceptible to infection by an Oomycete, Phytophthora cinnamomi, in the wild and this pathogen is strongly suspected of being responsible for the deaths of many other species in cultivation.

The sclerophyllous plant communities where Persoonia species usually live are fire-prone environments, hence Persoonia species have adapted to frequent bushfires. The most obvious adaptations are features that allow plants to survive fires, albeit in a more-or-less pruned state. Many species, especially in the south west, are lignotuberous, resprouting from ground level after fire. Several also develop thick bark that protects epicormic buds, which resprout from trunks and large branches after fire. The most eye-catching of these are the four “paper-barked” species: P. falcata, P. levis, P. linearis and P. longifolia. Branch resprouters with less conspicuous protective bark include P. amaliae, P. elliptica, P. katerae and P. stradbrokensis. Fire-sensitive species survive fires as buried seeds, which tend to germinate prolifically after disturbance. These species seem to require an interval of at least eight years between fires, allowing newly germinated plants to reach reproductive maturity and establish a replacement seed bank. The natural patterns and processes involved in this kind of life cycle, including seed longevity, the environmental cues that stimulate germination, and even the time from germination to first flowering are still poorly understood.

The best studied interaction between animals and Persoonia species is that between the plants and their pollinators. All species that have been studied in detail have been found to be pollinated by a variety of native bees, but especially species of Leioproctus subgenus Cladocerapis (Colletidae), which rarely visit any plants but Persoonia. The behaviour of these bees on Persoonia flowers is quite predictable. Both males and females alight on the cross-shaped “platform” formed by the recurved anther tips, orient themselves to be facing one of the anther/tepals, then slide, face first, down between the anther and the style to reach the two glands at either side of the base of the tepal, and drink the nectar from them. Females gather pollen grains with their legs while drinking nectar. The insect then withdraws to the top of the flower, makes a 180° turn, then repeats the process on the other side of the flower. Another species group in Leioproctus, subgenus Filiglossa, also specialises in feeding on Persoonia flowers but these smaller bees seem to be nectar and pollen “thieves”, not effective pollinators. The introduced honeybee (Apis mellifera) is also a frequent visitor of Persoonia flowers at most sites but it is still unclear whether this species is an effective pollinator. The fleshy fruits of Persoonia species are clearly adapted for animal dispersal but it is still unclear whether mammals such as possums and wallabies, or large flying birds such as currawongs are the most important dispersers. Parrots, also feed on Persoonia fruits, but the fruit (and seed) they eat are unripe, and hence their interaction with the plants is predatory rather than symbiotic.

Species

- Persoonia acerosa

- Persoonia acicularis

- Persoonia acuminata

- Persoonia adenantha

- Persoonia amaliae

- Persoonia angustiflora

- Persoonia arborea – tree geebung

- Persoonia asperula – mountain geebung

- Persoonia baeckeoides

- Persoonia bargoensis – Bargo geebung

- Persoonia biglandulosa

- Persoonia bowgada

- Persoonia brachystylis

- Persoonia brevifolia

- Persoonia brevirhachis

- Persoonia chamaepeuce – yellow geebung, dwarf geebung

- Persoonia chamaepitys – prostrate geebung, mountain geebung

- Persoonia chapmaniana

- Persoonia comata

- Persoonia confertiflora – cluster-flower geebung

- Persoonia conjuncta

- Persoonia cordifolia

- Persoonia coriacea – leathery-leaf persoonia

- Persoonia cornifolia

- Persoonia curvifolia

- Persoonia cuspidifera

- Persoonia cymbifolia

- Persoonia daphnoides

- Persoonia dillwynioides

- Persoonia elliptica – snottygobble

- Persoonia falcata – wild pear

- Persoonia fastigiata

- Persoonia filiformis

- Persoonia flexifolia

- Persoonia glaucescens – Mittagong geebung

- Persoonia graminea

- Persoonia gunnii – mountain geebung

- Persoonia hakeiformis

- Persoonia helix

- Persoonia hexagona

- Persoonia hindii

- Persoonia hirsuta – hairy persoonia, hairy geebung

- Persoonia inconspicua

- Persoonia iogyna

- Persoonia isophylla

- Persoonia juniperina – prickly geebung

- Persoonia kararae

- Persoonia katerae

- Persoonia lanceolata – lance-leaf geebung

- Persoonia laurina – laurel-leaved geebung, laurel geebung

- Persoonia laxa

- Persoonia leucopogon

- Persoonia levis – broad-leaved geebung

- Persoonia linearis – narrow-leaved geebung

- Persoonia longifolia – long-leaf persoonia

- Persoonia manotricha

- Persoonia marginata – Clandulla geebung

- Persoonia media

- Persoonia micranthera – small-flowered snottygobble

- Persoonia microphylla

- Persoonia mollis

- Persoonia moscalii – creeping geebung

- Persoonia muelleri – Mueller’s geebung

- Persoonia myrtilloides – myrtle geebung

- Persoonia nutans – nodding geebung

- Persoonia oblongata

- Persoonia oleoides

- Persoonia oxycoccoides

- Persoonia papillosa

- Persoonia pauciflora – North Rothbury persoonia

- Persoonia pentasticha

- Persoonia pertinax

- Persoonia pinifolia – pine-leaved geebung

- Persoonia procumbens

- Persoonia prostrata

- Persoonia pungens

- Persoonia quinquenervis

- Persoonia recedens

- Persoonia rigida – rigid, hairy, or stiff geebung

- Persoonia rudis

- Persoonia rufa

- Persoonia rufiflora

- Persoonia saccata

- Persoonia saundersiana

- Persoonia scabra

- Persoonia sericea – silky geebung

- Persoonia silvatica

- Persoonia spathulata

- Persoonia stradbrokensis

- Persoonia striata

- Persoonia stricta

- Persoonia subtilis

- Persoonia subvelutina – velvety geebung

- Persoonia sulcata

- Persoonia tenuifolia

- Persoonia teretifolia

- Persoonia terminalis – Torrington geebung

- Persoonia trinervis

- Persoonia tropica

- Persoonia virgata

- Persoonia volcanica

References

- Bernhardt, Peter (2002). The Rose's Kiss: A Natural History of Flowers. University of Chicago Press. p. 118. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Weston, Peter H. "Genus Persoonia". Royal Botanic Garden Sydney. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Jeanes, Jeff A. "Persoonia". Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Persoonia Sm". Western Australian Herbarium. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Persoonia". APNI. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Smith, James Edward (1798). "The Characters of Twenty New Genera of Plants. 4:". Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. 4: 215–216. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Persoonia Sm". APNI. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Australian National Botanic Gardens (2007). "Aboriginal Plant Use - NSW Southern Tablelands: Geebung". Canberra, Australian Capital Territory: Department of the Environment and Heritage. Retrieved 5 November 2011.

- Wright, Joseph (1905). The English Dialect Dictionary (Volume V). Amen Corner, London: Henry Frowde. p. 594.

- Crib, Alan B.; Crib, Joan W. (1980). Wild food in Australia. Sydney: Collins. p. 49. ISBN 0006344364.

- Holmes, G. D., Weston, P. H., Murphy, D. J., Connelly, C., & Cantrill, D. J. (2018). The genealogy of geebungs: phylogenetic analysis of Persoonia (Proteaceae) and related genera in subfamily Persoonioideae. Australian Systematic Botany, 31(2), 166-189.

Further reading

- Bernhardt, P.; Weston, P. H. (1996). "The pollination ecology of Persoonia (Proteaceae) in eastern Australia". Telopea. 6: 775–804.

- Maynard, G. V. (1995). "Pollinators of Australian Proteaceae". In McCarthy, Patrick (ed.). Flora of Australia: Volume 16: Eleagnaceae, Proteaceae 1. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 30–33. ISBN 0-643-05693-9.

- Weston, P. H. (1995). "Persoonioideae". In McCarthy, Patrick (ed.). Flora of Australia: Volume 16: Eleagnaceae, Proteaceae 1. CSIRO Publishing / Australian Biological Resources Study. pp. 47–125. ISBN 0-643-05693-9.

- Weston, Peter H. (2003). "Proteaceae subfamily Persoonioideae". Australian Plants. 22 (175): 62–78. ISSN 0005-0008.

External links