Arecaceae

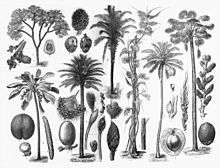

The Arecaceae are a botanical family of perennial flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are colloquially called palm trees.[3] Currently 181 genera with around 2,600 species are known,[4] most of them restricted to tropical and subtropical climates. Most palms are distinguished by their large, compound, evergreen leaves, known as fronds, arranged at the top of an unbranched stem. However, palms exhibit an enormous diversity in physical characteristics and inhabit nearly every type of habitat within their range, from rainforests to deserts.

| Arecaceae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coconut (Cocos nucifera) in Martinique | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae Bercht. & J.Presl, nom. cons.[1] |

| Type genus | |

| Areca | |

| Subfamilies | |

| Diversity | |

| Well over 2600 species in some 202 genera | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Palms are among the best known and most extensively cultivated plant families. They have been important to humans throughout much of history. Many common products and foods are derived from palms. In contemporary times, palms are also widely used in landscaping, making them one of the most economically important plants. In many historical cultures, because of their importance as food, palms were symbols for such ideas as victory, peace, and fertility. For inhabitants of cooler climates today, palms symbolize the tropics and vacations.[5]

Etymology

The word Arecaceae is derived from the word areca with the suffix "-aceae".[6] Areca is derived from Portuguese, via Malayalam അടയ്ക്ക (aṭaykka), which is from Proto-Dravidian *aṭ-ay-kkāy (“areca nut”).[7][8] The suffix -aceae is the feminine plural of the Latin -āceus ("resembling").

Morphology

Whether as shrubs, tree-like, or vines, palms have two methods of growth: solitary or clustered. The common representation is that of a solitary shoot ending in a crown of leaves. This monopodial character may be exhibited by prostrate, trunkless, and trunk-forming members. Some common palms restricted to solitary growth include Washingtonia and Roystonea. Palms may instead grow in sparse though dense clusters. The trunk develops an axillary bud at a leaf node, usually near the base, from which a new shoot emerges. The new shoot, in turn, produces an axillary bud and a clustering habit results. Exclusively sympodial genera include many of the rattans, Guihaia, and Rhapis. Several palm genera have both solitary and clustering members. Palms which are usually solitary may grow in clusters and vice versa. These aberrations suggest the habit operates on a single gene.[9]

Palms have large, evergreen leaves that are either palmately ('fan-leaved') or pinnately ('feather-leaved') compound and spirally arranged at the top of the stem. The leaves have a tubular sheath at the base that usually splits open on one side at maturity.[10] The inflorescence is a spadix or spike surrounded by one or more bracts or spathes that become woody at maturity. The flowers are generally small and white, radially symmetric, and can be either uni- or bisexual. The sepals and petals usually number three each, and may be distinct or joined at the base. The stamens generally number six, with filaments that may be separate, attached to each other, or attached to the pistil at the base. The fruit is usually a single-seeded drupe (sometimes berry-like)[11] but some genera (e.g., Salacca) may contain two or more seeds in each fruit.

Like all monocots, palms do not have the ability to increase the width of a stem (secondary growth) via the same kind of vascular cambium found in non-monocot woody plants.[12] This explains the cylindrical shape of the trunk (almost constant diameter) that is often seen in palms, unlike in ring-forming trees. However, many palms, like some other monocots, do have secondary growth, although because it does not arise from a single vascular cambium producing xylem inwards and phloem outwards, it is often called "anomalous secondary growth".[13]

The Arecaceae are notable among monocots for their height and for the size of their seeds, leaves, and inflorescences. Ceroxylon quindiuense, Colombia's national tree, is the tallest monocot in the world, reaching up to 60 m tall.[14] The coco de mer (Lodoicea maldivica) has the largest seeds of any plant, 40–50 cm in diameter and weighing 15–30 kg each (coconuts are the second largest). Raffia palms (Raphia spp.) have the largest leaves of any plant, up to 25 m long and 3 m wide. The Corypha species have the largest inflorescence of any plant, up to 7.5 m tall and containing millions of small flowers. Calamus stems can reach 200 m in length.

Range and habitat

Most palms are native to tropical and subtropical climates. Palms thrive in moist and hot climates but can be found in a variety of different habitats. Their diversity is highest in wet, lowland forests. South America, the Caribbean, and areas of the south Pacific and southern Asia are regions of concentration. Colombia may have the highest number of palm species in one country. There are some palms that are also native to desert areas such as the Arabian peninsula and parts of northwestern Mexico. Only about 130 palm species naturally grow entirely beyond the tropics, mostly in humid lowland subtropical climates, in highlands in southern Asia, and along the rim lands of the Mediterranean Sea. The northernmost native palm is Chamaerops humilis, which reaches 44°N latitude along the coast of Liguria, Italy.[15] In the southern hemisphere, the southernmost palm is the Rhopalostylis sapida, which reaches 44°S on the Chatham Islands where an oceanic climate prevails.[16] Cultivation of palms is possible north of subtropical climates, and some higher latitude locals such as Ireland, Scotland, England, and the Pacific Northwest feature a few palms in protected locations and microclimates.

Palms inhabit a variety of ecosystems. More than two-thirds of palm species live in humid moist forests, where some species grow tall enough to form part of the canopy and shorter ones form part of the understory.[17] Some species form pure stands in areas with poor drainage or regular flooding, including Raphia hookeri which is common in coastal freshwater swamps in West Africa. Other palms live in tropical mountain habitats above 1000 m, such as those in the genus Ceroxylon native to the Andes. Palms may also live in grasslands and scrublands, usually associated with a water source, and in desert oases such as the date palm. A few palms are adapted to extremely basic lime soils, while others are similarly adapted to extreme potassium deficiency and toxicity of heavy metals in serpentine soils.[16]

Palms are a monophyletic group of plants, meaning the group consists of a common ancestor and all its descendants.[17] Extensive taxonomic research on palms began with botanist H.E. Moore, who organized palms into 15 major groups based mostly on general morphological characteristics. The following classification, proposed by N.W. Uhl and J. Dransfield in 1987, is a revision of Moore's classification that organizes palms into six subfamilies.[18]

- Coryphoideae

- Calamoideae

- Nypoideae

- Ceroxyloideae

- Arecoideae

- Phytelephantoideae

A few general traits of each subfamily are listed below.

The Coryphoideae are the most diverse subfamily, and are a paraphyletic group, meaning all members of the group share a common ancestor, but the group does not include all the ancestor's descendants. Most palms in this subfamily have palmately lobed leaves and solitary flowers with three, or sometimes four carpels. The fruit normally develops from only one carpel.

Subfamily Calamoideae includes the climbing palms, such as rattans. The leaves are usually pinnate; derived characters (synapomorphies) include spines on various organs, organs specialized for climbing, an extension of the main stem of the leaf-bearing reflexed spines, and overlapping scales covering the fruit and ovary.

Subfamily Nypoideae contains only one species, Nypa fruticans,[19] which has large, pinnate leaves. The fruit is unusual in that it floats, and the stem is dichotomously branched, also unusual in palms.

Subfamily Ceroxyloideae has small to medium-sized flowers, spirally arranged, with a gynoecium of three joined carpels.

The Arecoideae are the largest subfamily, with six diverse tribes (Areceae, Caryoteae, Cocoseae, Geonomeae, Iriarteeae, and Podococceae) containing over 100 genera. All tribes have pinnate or bipinnate leaves and flowers arranged in groups of three, with a central pistillate and two staminate flowers.

The Phytelephantoideae are a monoecious subfamily. Members of this group have distinct monopodial flower clusters. Other distinct features include a gynoecium with five to 10 joined carpels, and flowers with more than three parts per whorl. Fruits are multiple-seeded and have multiple parts.[20]

Currently, few extensive phylogenetic studies of the Arecaceae exist. In 1997, Baker et al. explored subfamily and tribe relationships using chloroplast DNA from 60 genera from all subfamilies and tribes. The results strongly showed the Calamoideae are monophyletic, and Ceroxyloideae and Coryphoideae are paraphyletic. The relationships of Arecoideae are uncertain, but they are possibly related to the Ceroxyloideae and Phytelephantoideae. Studies have suggested the lack of a fully resolved hypothesis for the relationships within the family is due to a variety of factors, including difficulties in selecting appropriate outgroups, homoplasy in morphological character states, slow rates of molecular evolution important for the use of standard DNA markers, and character polarization.[21] However, hybridization has been observed among Orbignya and Phoenix species, and using chloroplast DNA in cladistic studies may produce inaccurate results due to maternal inheritance of the chloroplast DNA. Chemical and molecular data from non-organelle DNA, for example, could be more effective for studying palm phylogeny.[20]

Selected genera

- Archontophoenix—Bangalow palm

- Areca—Betel palm

- Astrocaryum

- Attalea

- Bactris—Pupunha

- Beccariophoenix—Beccariophoenix alfredii

- Bismarckia—Bismarck palm

- Borassus—Palmyra palm, sugar palm, toddy palm

- Butia

- Calamus—Rattan palm

- Ceroxylon

- Cocos—Coconut

- Coccothrinax

- Copernicia—Carnauba wax palm

- Corypha—Gebang palm, Buri palm or Talipot palm

- Elaeis—Oil palm

- Euterpe—Cabbage heart palm, açaí palm

- Hyphaene—Doum palm

- Jubaea—Chilean wine palm, Coquito palm

- Latania—Latan palm

- Licuala

- Livistona—Cabbage palm

- Mauritia—Moriche palm

- Metroxylon—Sago palm

- Nypa—Nipa palm

- Parajubaea—Bolivian coconut palms

- Phoenix—Date palm

- Phoenix sylvestris—Wild date palm

- Pritchardia

- Raphia—Raffia palm

- Rhapidophyllum

- Rhapis

- Roystonea—Royal palm

- Sabal—Palmettos

- Salacca—Salak

- Syagrus—Queen palm

- Thrinax

- Trachycarpus—Windmill palm, Kumaon palm

- Trithrinax

- Veitchia—Manila palm, Joannis palm

- Washingtonia—Fan palm

Evolution

The Arecaceae are the first modern family of monocots appearing in the fossil record around 80 million years ago (Mya), during the late Cretaceous period. The first modern species, such as Nypa fruticans and Acrocomia aculeata, appeared 94 Mya, confirmed by fossil Nypa pollen dated to 94 Mya. Palms appear to have undergone an early period of adaptive radiation. By 60 Mya, many of the modern, specialized genera of palms appeared and became widespread and common, much more widespread than their range today. Because palms separated from the monocots earlier than other families, they developed more intrafamilial specialization and diversity. By tracing back these diverse characteristics of palms to the basic structures of monocots, palms may be valuable in studying monocot evolution.[22] Several species of palms have been identified from flowers preserved in amber, including Palaeoraphe dominicana and Roystonea palaea.[23] Evidence can also be found in samples of petrified palmwood.

Uses

Human use of palms is as old or older than human civilization itself, starting with the cultivation of the date palm by Mesopotamians and other Middle Eastern peoples 5000 years or more ago.[24] Date wood, pits for storing dates, and other remains of the date palm have been found in Mesopotamian sites.[25] The date palm had a tremendous effect on the history of the Middle East. W.H. Barreveld wrote:

One could go as far as to say that, had the date palm not existed, the expansion of the human race into the hot and barren parts of the "old" world would have been much more restricted. The date palm not only provided a concentrated energy food, which could be easily stored and carried along on long journeys across the deserts, it also created a more amenable habitat for the people to live in by providing shade and protection from the desert winds (Fig. 1). In addition, the date palm also yielded a variety of products for use in agricultural production and for domestic utensils, and practically all parts of the palm had a useful purpose.[24]

An indication of the importance of palms in ancient times is that they are mentioned more than 30 times in the Bible,[26] and at least 22 times in the Quran.[27]

Arecaceae have great economic importance, including coconut products, oils, dates, palm syrup, ivory nuts, carnauba wax, rattan cane, raffia, and palm wood.

Along with dates mentioned above, members of the palm family with human uses are numerous.

- The type member of Arecaceae is the areca palm, the fruit of which, the areca nut, is chewed with the betel leaf for intoxicating effects (Areca catechu).

- Carnauba wax is harvested from the leaves of a Brazilian palm (Copernicia).

- Rattans, whose stems are used extensively in furniture and baskets, are in the genus Calamus.

- Palm oil is an edible vegetable oil produced by the oil palms in the genus Elaeis.

- Several species are harvested for heart of palm, a vegetable eaten in salads.

- Sap of the nipa palm, Nypa fruticans, is used to make vinegar.

- Palm sap is sometimes fermented to produce palm wine or toddy, an alcoholic beverage common in parts of Africa, India, and the Philippines. The sap may be drunk fresh, but fermentation is rapid, reaching up to 4% alcohol content within an hour, and turning vinegary in a day.[28]

- Palmyra and date palm sap is harvested in Bengal, India, to process into gur and jaggery.

- Dragon's blood, a red resin used traditionally in medicine, varnish, and dyes, may be obtained from the fruit of Daemonorops species.

- Coconut is the partially edible seed of the fruit of the coconut palm (Cocos nucifera).

- Coir is a coarse, water-resistant fiber extracted from the outer shell of coconuts, used in doormats, brushes, mattresses, and ropes. In India, beekeepers use coir in their bee smokers.

- Some indigenous groups living in palm-rich areas use palms to make many of their necessary items and food. Sago, for example, a starch made from the pith of the trunk of the sago palm Metroxylon sagu, is a major staple food for lowland peoples of New Guinea and the Moluccas. This is not the same plant commonly used as a house plant and called "sago palm".

- Palm wine is made from Jubaea also called Chilean wine palm, or coquito palm

- Recently, the fruit of the açaí palm Euterpe has been used for its reputed health benefits.

- Saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) is under investigation as a drug for treating enlarged prostates.

- Palm leaves are also valuable to some peoples as a material for thatching, basketry, clothing, and in religious ceremonies (see "Symbolism" below).[16]

- Ornamental uses: Today, palms are valuable as ornamental plants and are often grown along streets in tropical and subtropical cities. Chamaedorea elegans is a popular houseplant and is grown indoors for its low maintenance. Farther north, palms are a common feature in botanical gardens or as indoor plants. Few palms tolerate severe cold and the majority of the species are tropical or subtropical. The three most cold-tolerant species are Trachycarpus fortunei, native to eastern Asia, and Rhapidophyllum hystrix and Sabal minor, both native to the southeastern United States.

- The southeastern U.S. state of South Carolina is nicknamed the Palmetto State after the sabal palmetto (cabbage palmetto), logs from which were used to build the fort at Fort Moultrie. During the American Revolutionary War, they were invaluable to those defending the fort, because their spongy wood absorbed or deflected the British cannonballs.[29]

- Singaporean politician Tan Cheng Bock uses a palm tree-like symbol similar to a Ravenala to represent him in the 2011 Singaporean presidential election.[30]. The symbol of a party he founded, Progress Singapore Party, was also based on a palm tree.[31][32]

Fruit of the date palm Phoenix dactylifera

Fruit of the date palm Phoenix dactylifera Washingtonia robusta palms line Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica, California.

Washingtonia robusta palms line Ocean Avenue in Santa Monica, California.- Sabal palm in the Canaveral National Seashore

Coconut flowers

Coconut flowers

Endangered species

Like many other plants, palms have been threatened by human intervention and exploitation. The greatest risk to palms is destruction of habitat, especially in the tropical forests, due to urbanization, wood-chipping, mining, and conversion to farmland. Palms rarely reproduce after such great changes in the habitat, and those with small habitat ranges are most vulnerable to them. The harvesting of heart of palm, a delicacy in salads, also poses a threat because it is derived from the palm's apical meristem, a vital part of the palm that cannot be regrown (except in domesticated varieties, e.g. of peach palm).[33] The use of rattan palms in furniture has caused a major population decrease in these species that has negatively affected local and international markets, as well as biodiversity in the area.[34] The sale of seeds to nurseries and collectors is another threat, as the seeds of popular palms are sometimes harvested directly from the wild. At least 100 palm species are currently endangered, and nine species have reportedly recently become extinct.[17]

However, several factors make palm conservation more difficult. Palms live in almost every type of warm habitat and have tremendous morphological diversity. Most palm seeds lose viability quickly, and they cannot be preserved in low temperatures because the cold kills the embryo. Using botanical gardens for conservation also presents problems, since they can rarely house more than a few plants of any species or truly imitate the natural setting.[35] Also, the risk of cross-pollination can lead to hybrid species.

The Palm Specialist Group of the World Conservation Union (IUCN) began in 1984, and has performed a series of three studies to find basic information on the status of palms in the wild, use of wild palms, and palms under cultivation. Two projects on palm conservation and use supported by the World Wildlife Fund took place from 1985 to 1990 and 1986–1991, in the American tropics and southeast Asia, respectively. Both studies produced copious new data and publications on palms. Preparation of a global action plan for palm conservation began in 1991, supported by the IUCN, and was published in 1996.[35]

The rarest palm known is Hyophorbe amaricaulis. The only living individual remains at the Botanic Gardens of Curepipe in Mauritius.

Arthropod pests

Pests that attack a variety of species of palms include:

- Raoiella indica, the red palm mite[36]

- Caryobruchus gleditsiae, the palm seed beetle or palm seed weevil[37]

- Rhynchophorus ferrugineus, the red palm weevil, recently introduced to Europe[38][39]

Symbolism

The palm branch was a symbol of triumph and victory in classical antiquity. The Romans rewarded champions of the games and celebrated military successes with palm branches. Early Christians used the palm branch to symbolize the victory of the faithful over enemies of the soul, as in the Palm Sunday festival celebrating the triumphal entry of Jesus Christ into Jerusalem. In Judaism, the palm represents peace and plenty, and is one of the Four Species of Sukkot; the palm may also symbolize the Tree of Life in Kabbalah.

Panaiveriyamman was an ancient Tamil tree deity related to fertility. Named after panai, the Tamil name for the Palmyra palm, she was also known as Taalavaasini, a name that further related her to all types of palms.[40]

The canopies of the Rathayatra carts which carry the deities of Krishna and his family members in the cart festival of Jagganath Puri in India are marked with the emblem of a palm tree. Specifically it is the symbol of Krishna's brother, Baladeva.

Today, the palm, especially the coconut palm, remains a symbol of the tropical island paradise.[17] Palms appear on the flags and seals of several places where they are native, including those of Haiti, Guam, Saudi Arabia, Florida, and South Carolina.

Other plants

Some species commonly called palms, though they are not true palms, include:

- Cordyline australis[41] (Torbay palm, ti palm,[41] palm lily[41]) (family Asparagaceae) and other representatives in the genus Cordyline and perhaps also in Dracaena with which Cordyline may be confused.

- Cycas revoluta (Sago palm[41]) and the rest of the order Cycadales

- Ravenala (Traveller's palm[41]) (family Strelitziaceae)

- Pandanus spiralis, Screw palm.,[41] and perhaps other Pandanus spp.

- Cyathea cunninghamii (Palm fern[41]) and other Tree ferns (families Cyatheaceae and Dicksoniaceae) that may be confused with palms.

- Setaria palmifolia (Palm grass[41]), a Poaceae.

- Carludovica palmata (Panama hat palm[41]) and perhaps other members in the family Cyclanthaceae.

- Yucca brevifolia (Joshua tree, or palm tree yukka), and Yucca aloifolia, of genus Yucca in family Asparagaceae.

See also

- Coconut

- Fan palm—genera with palmate leaves

- List of Arecaceae genera

- List of foliage plant diseases (Palmae)

- List of hardy palms—palms able to withstand colder temperatures

- Palm wine—palm tree wine-making process

- Postelsia—called the "sea palm" (a brown alga)

References

Citations

- Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009), "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 161 (2): 105–121, doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x, archived from the original on 2017-05-25, retrieved 2010-12-10

- "Arecaceae Bercht. & J. Presl, nom. cons". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 2007-04-13. Archived from the original on 2009-08-11. Retrieved 2009-07-18.

- The name "Palmaceae" is not accepted because the name Arecaceae (and its acceptable alternative Palmae, ICBN Art. 18.5 Archived 2006-05-24 at the Wayback Machine) are conserved over other names for the palm family.

- Christenhusz, M. J. M. & Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1. Archived from the original on 2016-07-29.

- Landscaping with Palms in the Mediterranean Archived June 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Arecaceae - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- "areca - Wiktionary". en.wiktionary.org. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- "Areca", Wikipedia, 2019-08-19, retrieved 2019-09-04

- Uhl, Natalie W. and Dransfield, John (1987) Genera Palmarum – A classification of palms based on the work of Harold E. Moore. Lawrence, Kansas: Allen Press. ISBN 0-935868-30-5 / ISBN 978-0-935868-30-2

- Arecaceae – University of Hawaii Botany Archived 2006-04-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Zona, Scott (2000). "Arecaceae". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). 22. New York and Oxford. Archived from the original on 2006-05-25 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Chase, Mark W. (2004). "Monocot relationships: an overview". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1645–1655. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1645. PMID 21652314.

- Donoghue, Michael J. (2005). "Key innovations, convergence, and success: macroevolutionary lessons from plant phylogeny" (PDF). Paleobiology. 31: 77–93. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2005)031[0077:KICASM]2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-07-23.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- :: Presidencia de la República de Colombia :: Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- Francesco Orsino & Silvia Olivari (1987) The presence of Chamaerops humilis L. on Portofino promontory (East Liguria), Webbia, 41:2, 261-272

- Tropical Palms by Food and Agriculture Organization Archived May 6, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Virtual Palm Encyclopedia – Introduction Archived 2006-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- N. W. Uhl, J. Dransfield (1987). Genera palmarum: a classification of palms based on the work of Harold E. Moore, Jr. (Allen Press, Lawrence, Kansas).

- John Leslie Dowe (2010). Australian Palms: Biogeography, Ecology and Systematics. p. 83. ISBN 9780643096158. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- Palms on the University of Arizona Campus Archived June 21, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Hahn, W.J. (2002). A Molecular Phylogenetic Study of the Palmae (Arecaceae) Based on atpB, rbcL, and 18S nrDNA Sequences (Systematic Botany 51(1): 92–112).

- Virtual Palm Encyclopedia – Evolution and the fossil record Archived 2006-04-18 at the Wayback Machine

- Poinar, G. (2002). "Fossil palm flowers in Dominican and Baltic amber". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 139 (4): 361–367. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2002.00052.x.

- W.H. Barreveld. "Date Palm Products – Introduction". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Archived from the original on 19 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- Date Sex @ University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Archived 2004-01-13 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- Bible search for "palm" Archived 2007-03-10 at the Wayback Machine

- Koran search for "palm"

- Battcock, Mike; Azam-Ali, Sue. "Chapter Four: Products of Yeast Fermentation". Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Revolutionary War Exhibit Text – November 2002 Archived November 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- See, Sharon (18 August 2011). "PE: Candidates unveil election symbols". Channel News Asia. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- "Tan Cheng Bock cries twice speaking about succession & party recruitment at PSP launch event". Mothership. Retrieved 2019-08-04.

- "PSP can help people take up issues only if voted into Parliament, says Tan Cheng Bock at party launch". The Straits Times. 3 August 2019.

- Rose Kahele (August–September 2007). "Big Island Hearts". Hana Hou! Vol. 10, No. 4. Archived from the original on 2016-08-26. Retrieved 2016-08-14.

- Dennis Johnson, ed. (1996). Palms: Their Conservation and Sustained Utilization (PDF). International Union for Conservation of Nature. ISBN 978-2-8317-0352-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-01-14. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- Palm Conservation: Its Atecedents, Status, and Needs Archived 2006-08-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "Pest Alerts - Red palm mite, DPI - FDACS". Doacs.state.fl.us. Archived from the original on 2010-12-02. Retrieved 2010-07-30.

- Robert E. Woodruff (1968). "The palm seed "weevil," Caryobruchus gleditsiae (L.) in Florida (Coleoptera: Bruchidae)" (PDF). Entomology Circular. 73: 1–2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24.

- Rhynchophorus ferrugineus Archived 2007-07-23 at the Wayback Machine at North American Plant Protection Organization (NAPPO)

- Ferry & Gómez. 2002. The red palm weevil in the Mediterranean. Vol. 46, No 4, Palms (formerly Principes), Journal of the International Palm Society. link Archived 2009-02-27 at the Wayback Machine link

- Symbolism of trees Archived 2016-01-23 at the Wayback Machine

- (c) FAO 1995. Tropical Palms.. Introduction. "Tropical Palms - Introduction". Archived from the original on 2006-08-31. Retrieved 2006-07-15. NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 10. FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 92-5-104213-6

General sources

- Dransfield J., Uhl N.W., Asmussen C.B., Baker W.J., Harley M.M., Lewis C.E. (January 2005). "A new phylogenetic classification of the palm family, Arecaceae". Kew Bulletin 60: 559–569. (Latest Arecaceae or Palmae classification.)

- Hahn, W. J. (February 2002). "A Molecular Phylogenetic Study of the Palmae (Arecaceae) Based on atpB, rbcL, and 18S nrDNA Sequences". Systematic Botany 51(1): 92–112. JSTOR 3070898.

- Schultz-Schultzenstein, C. H. (1832). Natürliches System des Pflanzenreichs..., p. 317. Berlin, Germany. (in German)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arecaceae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Arecaceae |

- Palmpedia—A wiki-based site dedicated to high quality images and information on palm trees.

- Fairchild Guide to Palms—A collection of palm images, scientific data, and horticultural information hosted by Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden, Miami.

- Kew Botanic Garden's Palm Genera list—A list of the currently acknowledged genera by Kew Royal Botanic Gardens in London, England (Archived 2007)

- Palm species listing with images—Palm and Cycad Societies of Australia (PACSOA)

- Palm & Cycad Societies of Florida, Inc. (PACSOF), which includes pages on Arecaceae taxonomy and a photo index.

- Sterken, Peter (2008). "The Elastic Stability of Palms" (PDF). Plant Science Bulletin. 54 (4). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2008.

- Palmaceae in the BoDD—Botanical Dermatology Database