Ore Mountains

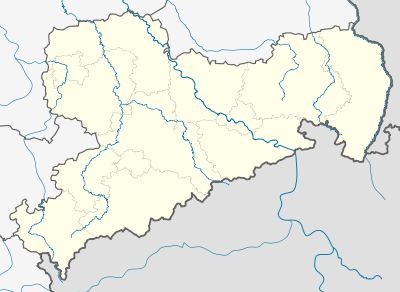

The Ore Mountains or Ore Mountain Range[1] ( /ɔːr/) (German: Erzgebirge [ˈeːɐ̯tsɡəˌbɪʁɡə]; Czech: Krušné hory [ˈkruʃnɛː ˈhorɪ]; both literally "ore mountains"[2]) in Central Europe have formed a natural border between Saxony and Bohemia for around 800 years, from the 12th to the 20th centuries. Today, the border between Germany and the Czech Republic runs just north of the main crest of the mountain range. The highest peaks are the Klínovec (German: Keilberg), which rises to 1,244 metres (4,081 ft) above sea level and the Fichtelberg (1,215 metres (3,986 ft)).

| Ore Mountains | |

|---|---|

| Erzgebirge - Krušné hory | |

Reservoir near Myslivny | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Klínovec |

| Elevation | 1,244 m (4,081 ft) |

| Coordinates | 50°23′46″N 12°58′04″E |

| Geography | |

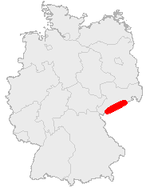

Location in Germany

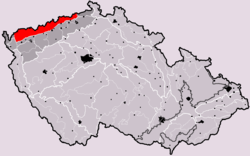

Location in the Czech Republic  | |

| Countries | Czech Republic and Germany |

| Regions/States | Karlovy Vary, Ústí nad Labem and Saxony |

| Range coordinates | 50°35′N 13°00′E |

| Geology | |

| Orogeny | Variscan |

| Age of rock | Paleozoic |

| Type of rock | sedimentary, metamorphic and igneous rocks |

| Climbing | |

| Official name | Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | (ii), (iii), (iv) |

| Designated | 2019 |

| Reference no. | 1478 |

| State Party | |

| Region | Western Europe/Eastern Europe |

The area played an important role in contributing Bronze Age ore, and as the setting of the earliest stages of the early modern transformation of mining and metallurgy from a craft to a large-scale industry, a process that preceded and enabled the later Industrial Revolution.

Geography

Geology

The Ore Mountains are a Hercynian block tilted so as to present a steep scarp face towards Bohemia and a gentle slope on the German side.[4] They were formed during a lengthy process:

During the folding of the Variscan orogeny, metamorphism occurred deep underground, forming slate and gneiss. In addition, granite plutons intruded into the metamorphic rocks. By the end of the Palaeozoic era, the mountains had been eroded into gently undulating hills (the Permian massif), exposing the hard rocks.

In the Tertiary period these mountain remnants came under heavy pressure as a result of plate tectonic processes during which the Alps were formed and the North American and Eurasian plates were separated. As the rock of the Ore Mountains was too brittle to be folded, it shattered into an independent fault block which was uplifted and tilted to the northwest. This can be very clearly seen at a height of 807 m above sea level (NN) on the mountain of Komáří vížka which lies on the Czech side, east of Zinnwald-Georgenfeld, right on the edge of the fault block.

Consequently, it is a fault-block mountain range which, today has been incised by a whole range of river valleys whose rivers drain southwards into the Eger and northwards into the Mulde or directly into the Elbe. This process is known as dissection.

The Ore Mountains are geologically considered to be one of the most heavily researched mountain ranges in the world.

The main geologic feature in the Ore Mountains is the Late Paleozoic Eibenstock granite pluton, which is exposed for 25 miles along its northwest–southeast axis and up to 15 miles in width. This pluton is surrounded by progressive zones of contact metamorphism in which Paleozoic slates and phyllites have been changed to spotted hornfels, andalusite hornfels, and quartzites. Two key mineral centers intersect this pluton at Joachimsthal, one trending northwesterly from Schneeberg through Johanngeorgenstadt to Joachimsthal, and a second trending north–south from Freiberg through Marienberg, Annaberg, Niederschlag, Joachimsthal, and Schlaggenwald. Late Tertiary faulting and volcanism gave rise to basalt and phonolite dikes. Ore veins include iron, copper, tin, tungsten, lead, silver, cobalt, bismuth, uranium, plus iron and manganese oxides.[5]

The most important rocks occurring in the Ore Mountains are schist, phyllite and granite with contact metamorphic zones in the west, basalt as remnants in the Plešivec (Pleßberg), Scheibenberg, Bärenstein, Pöhlberg, Velký Špičák (Großer Spitzberg or Schmiedeberger Spitzberg), Jelení hora (Haßberg) and Geisingberg as well as gneisses and rhyolite (Kahleberg) in the east. The soils consist of rapidly leaching grus. In the western and central areas of the mountains it is formed from weathered granite. Phyllite results in a loamy, rapidly weathered gneiss in the east of the mountains producing a light soil. As a result of the subsoils based on granite and rhyolite, the land is mostly covered in forest; on the gneiss soils it was possible to grow and cultivate flax in earlier centuries and, later, rye, oats and potatoes up to the highlands. Today the land is predominantly used for pasture. But it is not uncommon to see near-natural mountain meadows.

To the north of the Ore Mountains, west of Chemnitz and around Zwickau lies the Ore Mountain Basin which is only really known geologically. Here there are deposits of stone coal where mining has already been abandoned. A similar but smaller basin with abandoned coal deposits, the Döhlen Basin, is located southwest of Dresden on the northern edge of the Ore Mountains. It forms the transition to the Elbe Valley zone.

Terrain

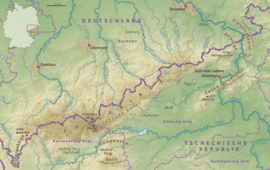

The western part of the Ore Mountains is home to the two highest peaks of the range: Klínovec, located in the Czech part, with an altitude of 1,244 metres (4,081 ft) and Fichtelberg, the highest mountain of Saxony, Germany, at 1,214 metres (3,983 ft). The Ore Mountains are part of a larger mountain system and adjoin the Fichtel Mountains to the west and the Elbe Sandstone Mountains to the east. Past the River Elbe, the mountain chain continues as the Lusatian Mountains. While the mountains slope gently away in the northern (German) part, the southern (Czech) slopes are rather steep.

Topography

The Ore Mountains are oriented in a southwest–northeast direction and are about 150 km long and, on average, about 40 km wide. From a geomorphological perspective the range is divided into the Western, Central and Eastern Ore Mountains, separated by the valleys of the Schwarzwasser and Zwickauer Mulde and the Flöha ("Flöha Line"), the division of the western section along the River Schwarzwasser is of a more recent date. The Eastern Ore Mountains mainly comprise large, gently climbing plateaux, in contrast with the steeper and higher-lying western and central areas, and are dissected by river valleys that frequently change direction. The crest of the mountains themselves forms, in all three regions, a succession of plateaux and individual peaks.

To the east it is adjoined by the Elbe Sandstone Mountains and, to the west, by the Elster Mountains and other Saxon parts of the Vogtland. South(east) of the Central and Eastern Ore Mountains lies the North Bohemian Basin and, immediately east of that, the Bohemian Central Uplands which are separated from the Eastern Ore Mountains by narrow fingers of the aforementioned basin. South(east) of the Western Ore Mountains lie the Sokolov Basin, the Eger Graben and the Doupov Mountains. To the north the boundary is less sharply defined because the Ore Mountains, a typical example of a fault-block, descend very gradually.

The topographical transition from the Western and Central Ore Mountains to the loess hill country to the north between Zwickau and Chemnitz is referred to as the Ore Mountain Basin; that from the Eastern Ore Mountains as the Ore Mountain Foreland. Between Freital and Pirna, the area is called the Dresden Ore Mountain Foreland (Dresdner Erzgebirgsvorland) or Bannewitz-Possendorf-Burkhardswald Plateau (Bannewitz-Possendorf-Burkhardswalder Plateau). Geologically the Ore Mountains reach the city limits of Dresden at the Windberg hill near Freital and the Karsdorf Fault. The V-shaped valleys of the Ore Mountains break through this fault and the shoulder of the Dresden Basin.

The Ore Mountains belong to the Bohemian Massif within Europe's Central Uplands, a massif that also includes the Upper Palatine Forest, the Bohemian Forest, the Bavarian Forest, the Lusatian Mountains, the Iser Mountains, the Giant Mountains and the Inner-Bohemian Mountains. At the same time it forms a y-shaped mountain chain, along with the Upper Palatine Forest, Bohemian Forest, Fichtel Mountains, Franconian Forest, Thuringian Slate Mountains and Thuringian Forest, that has no unique name but is characterised by a rather homogeneous climate.

According to cultural tradition, Zwickau is seen historically as part of the Ore Mountains, Chemnitz is seen historically as just lying outside them, but Freiberg is included. The supposed limit of the Ore Mountains continues southwest of Dresden towards the Elbe Sandstone Mountains. From this perspective, its main characteristics, i.e., gently sloping plateaus climbing up to the ridgeline incised by V-shaped valleys, continue to the southern edge of the Dresden Basin. North of the Ore Mountains the landscape gradually transitions into the Saxon Lowland and Saxon Elbeland. Its cultural-geographical transition to Saxon Switzerland in the area of the Müglitz and Gottleuba valleys is not sharply defined.

Notable peaks

The highest mountain in the Ore Mountains is the Klínovec (German: Keilberg), at 1,244 metres, in the Bohemian part of the range. The highest elevation on the Saxon side is the 1,215-metre-high Fichtelberg, which was the highest mountain in East Germany. The Ore Mountains contain about thirty summits with a height over 1,000 m above sea level (NN), but not all are clearly defined mountains. Most of them occur around the Klínovec and the Fichtelberg. About a third of them are located on the Saxon side of the border.

Natural regions in the Saxon Ore Mountains

In the division of Germany into natural regions that was carried out Germany-wide in the 1950s[6] the Ore Mountains formed major unit group 42:

- 42 Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

- 420 Southern slopes of the Ore Mountains (Südabdachung des Erzgebirges)

- 421 Upper Western Ore Mountains (Oberes Westerzgebirge)

- 422 Upper Eastern Ore Mountains (Oberes Osterzgebirge)

- 423 Lower Western Ore Mountains (Unteres Westerzgebirge)

- 424 Lower Eastern Ore Mountains (Unteres Osterzgebirge)

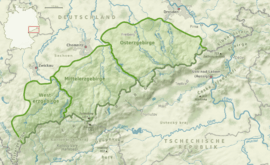

Even after the reclassification of natural regions by the Federal Agency for Nature Conservation in 1994 the Ore Mountains, region D16, remained a major unit group with almost unchanged boundaries. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, the working group Naturhaushalt und Gebietscharakter of the Saxon Academy of Sciences (Sächsische Akademie der Wissenschaften) in Leipzig merged the Ore Mountains with the major unit group of Vogtland to the west and the major landscape units of Saxon Switzerland, Lusatian Highlands and Zittau Mountains to the east into one overarching unit, the Saxon Highlands and Uplands. In addition, its internal divisions were changed. Former major unit 420 was grouped with the western part of major units 421 and 423 to form a new major unit, the Western Ore Mountains (Westerzgebirge), the eastern part of major units 421 and 423 became the Central Ore Mountains (Mittelerzgebirge) and major units 422 and 424 became the Eastern Ore Mountains (Osterzgebirge).

The current division therefore looks as follows:[7]

- Saxon Highlands and Uplands (Sächsisches Bergland und Mittelgebirge)

- Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

- Western Ore Mountains (Westerzgebirge)

- Central Ore Mountains (Mittelerzgebirge)

- Eastern Ore Mountains (Osterzgebirge)

- Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge)

The geographic unit of the Southern Slopes of the Ore Mountains remains unchanged under the title of Southern Ore Mountains (Süderzgebirge).

Climate

The climate of the higher regions of the Ore Mountains is characterised as distinctly harsh. Temperatures are considerably lower all year round than in the lowlands, and the summer is noticeably shorter and cool days are frequent. The average annual temperatures only reach values of 3 to 5 °C. In Oberwiesenthal, at a height of 922 m above sea level (NN), on average only about 140 frost-free days per year are observed. Based on reports of earlier chroniclers, the climate of the upper Ore Mountains in past centuries must have been even harsher than it is today. Historic sources describe hard winters in which cattle froze to death in their stables, and occasionally houses and cellars were snowed in even after snowfalls in April. The population was regularly cut off from the outside world.[8] The upper Ore Mountains was therefore nicknamed Saxon Siberia already in the 18th century.[9]

The fault block mountain range that climbs from northwest to southeast, and which enables prolonged rain to fall as orographic rain when weather systems drive in from the west and northwest, gives rise to twice as much precipitation as in the lowlands which exceeds 1,100 mm on the upper reaches of the mountains. Since a large part of the precipitation falls as snow, in many years a thick and permanent layer of snow remains until April. The ridges of the Ore Mountains are one of the snowiest areas in the German Central Uplands. Foehn winds, and also the so-called Bohemian Wind may occur during certain specific southerly weather conditions.

As a result of the climate and the heavy amounts of snow a natural Dwarf Mountain Pine region is found near Satzung, near the border to Bohemia at just under 900 m above sea level (NN). By comparison, in the Alps these pines do not occur until 1,600 to 1,800 m above sea level (NN).

History

Etymology of the name

The term Saltusbohemicus ("Bohemian Forest") for the region emerged in the 12th century. In the German language the names Böhmischer Wald, Beheimer Wald, Behmerwald or Böhmerwald were used, in Czech the name Český les. The last-mentioned names are used today for the mountain range along the Czech Republic's southwestern border (see: Bohemian Forest).

From earlier research, other names for the Ore Mountains have also appeared in a few older written records. However, the names Hircanus Saltus (Hercynian Forest) or Fergunna, which appeared in the 9th century, were only used in a general sense for the vast forests of the Central Uplands. Frequently the term Miriquidi is used to refer directly to the Ore Mountains, but it only surfaces twice in the 10th and early 11th centuries, and these sources do not permit a clear identification with the ancient forest that formerly covered the whole of the Ore Mountains and its foreland.

Following the discovery of large ore deposits the area was further renamed in the 16th century. Petrus Albinus used the name Erzgebirge ("Ore Mountains") for the first time in 1589, in his chronicle. In the early 17th century, the name Meißener Berge ("Meissen Mountains") was temporarily used. A quarter of a century later the names Erzgebirge in German and Rudohoří in Czech became established. The Czech toponym is ![]()

The mountains are sometimes divided into the Saxon Ore Mountains and Bohemian Ore Mountains. A similarly named range in Slovakia is usually known as the Slovak Ore Mountains.

Economic history

Europe's earliest mining district appears to be located in Erzgebirge, dated to 2500 BC. From there tin was traded north to the Baltic Sea and south to the Mediterranean following the Amber Road trading route, of great importance in the Bronze Age. Tin mining knowledge spread to other European tin mining districts from Erzgebirge and evidence of tin mining begins to appear in Brittany, Devon and Cornwall, and in the Iberian Peninsula around 2000 BC.[12] These deposits saw greater exploitation when they fell under Roman control between the third century BC and the first century AD.[13] Demand for tin created a large and thriving network amongst Mediterranean cultures of Classical times.[14][15] By the Medieval period, Iberia's and Germany's deposits lost importance and were largely forgotten while Devon and Cornwall began dominating the European tin market.[13]

From the time of the first wave of settlement, the history of the Ore Mountains has been heavily influenced by its economic development, especially that of the mining industry.

Settlement in the Ore Mountains was slow to begin with, especially on the Bohemian side. The harsh climate and short growing seasons hindered the cultivation of agricultural products. Nevertheless, settlements were supported by the aristocratic Hrabischitz family and established mainly at the foot of the mountains and along mountain streams into the deep woods.

In 1168, as a result of settlement in the early 12th century at the northern edge of the Ore Mountains, the first silver ore was discovered in the vicinity of present-day Freiberg, resulting in the First Berggeschrey or mining rush. Almost simultaneously, the first tin ore was discovered on the southern edge of the mountains in Bohemia.

In the 13th century, colonization of the mountains took place only sporadically along the Bohemian Way (antiqua Bohemiae semita). It was here that Sayda was built, a station on the trade route from Freiberg via Einsiedl, Johnsdorf and Brüx to Prague. In Sayda it joined the so-called salt road that ran from Halle via Oederan and onto Prague. Glass-making was introduced into the region from the second half of the 13th century. The emergence of this branch of trade benefited from the abundance of excess timber, which was created by clearings and new settlements and which was able to meet the high demand of the glassworks. Monks from Waldsassen Abbey brought a knowledge of the glass manufacture to the Ore Mountains. Most glassworks were located in the vicinity of Moldau, Brandau and the Frauenbach valley. The oldest glassworks site is Ulmbach. This timber-hungry industry lost its importance, however, with the boom in mining, which also enjoyed royal patronage.

Mining on the Bohemian side of the mountains probably began in the 14th century. An indication of this is a contract between Boresch of Riesenburg and the Ossegg abbot, Gerwig, in which the division of revenue derived from ore was agreed. Grains of tin (Zinnkörner or Graupen) were obtained at that time in the Seiffen mining area and gave the Bohemian mining town of Graupen (Czech Krupka) its name.

With the further settlement of the Ore Mountains in the 15th century, new, rich, ore deposits were eventually discovered around Schneeberg Annaberg and St. Joachimsthal. The Second Berggeschrey started and triggered a massive wave of colonization. In quick succession, new, planned, mining towns were built across the Ore Mountains in the vicinity of newly discovered ore deposits. Typical examples are the towns of Marienberg, Oberwiesenthal, Gottesgab (Boží Dar), Sebastiansberg (Hora Sv. Šebestiána) and Platten (Horní Blatná). Economically, however, only silver and tin ores were used. From that time, the wealth of Saxony was built on the silver mines of the Ore Mountains. As a metal used for coinage, silver was minted on site in the mountain towns into money. The Joachimsthaler coins, minted in the valley of Joachimsthal, became famous and gave their name to the medieval coin known as the Thaler from which the word "dollar" is derived.[16] After the end of the Hussite Wars, the economy in Bohemia, which had been disrupted by the conflict, recovered.

.jpg)

In the 16th century the Ore Mountains became the heartland of the Central European mining industry. New ore discoveries attracted more and more people, and the number of residents on the Saxon side of the mountains continued to rise rapidly. Bohemia, in addition to migration from within the country, also received migration from elsewhere, mainly of German miners, who settled in the mountain villages and in the towns at the edge of the mountains.

Under Emperor Ferdinand II an unprecedented Re-Catholicization began in Bohemia from 1624 to 1626, whereupon a large number of Bohemian Protestants then fled into the neighbouring Electorate of Saxony. As a result, many Bohemian villages became devastated and desolate, while on the Saxon side new places were founded by these migrants, such as the mining town of Johanngeorgenstadt.

Ore mining largely came to a standstill in the 17th century, especially after the Thirty Years' War. Due to the very sharp decline of the mining industry and because the search for new ore deposits proved fruitless, the population had to resort to other occupations. Agricultural yields were low, however, and also the demand for wood was reduced by the closure of smelteries. Many people were already active at that time in textile production. However, since that was not enough for subsistence, the manufacture of wooden goods and toys developed, especially in the Eastern Ore Mountains. Here, the artisans were required by Prince-Elector Augustus under the Timber Act of 1560, to buy their wood in Bohemia. Wood from the Saxon Ore Mountains was still needed for the mines and smelters in Freiberg. This export of timber led, among other things, to the construction of an artificial cross-border rafting channel, the Neugrabenflöße, along the river Flöha. Because of the decline in industrial production in that period, people without any ties migrated to the interior of Germany or Bohemia.

After the discovery of the cobalt blue pigments the mining industry experienced a revival.[5] Cobalt was extracted especially in Schneeberg, and processed in the state paintworks to produce cobalt blue paints and dyes. They succeeded in keeping the method of production secret for a long time, so that for about 100 years the blue colour works had a worldwide monopoly. From about 1820 in Johanngeorgenstadt, uranium was also extracted and was then used to colour glass, amongst other things. Even richer deposits of uranium ore were found in St. Joachimsthal. St. Andrew's White Earth Mine (Weißerdenzeche St. Andreas) at Aue supplied kaolin to the Meissen Porcelain Factory in Meissen for nearly 150 years. Its export from the state, however, was prohibited by the Prince-electors under threat of severe punishment or even death.

Towards the end of the 19th century, mining slowly declined again. Drainage costs increased, from the mid-19th century, led to a steady decrease in yield, despite sinking of deeper galleries (Erbstollen) and the expansion of ditch and tunnel (Rösche) systems for supplying the necessary water for overshot wheels from the crest of the mountains, such as the Freiberg Mines Water Management System or the Reitzenhainer Zeuggraben. Only a few mines remained profitable over a long period. Amongst them was the Himmelsfürst Fundgrube near Erbisdorf, whose 50 continuous years of profitable operation were commemorated in 1818 with the issue of a commemorative coin (Ausbeutetaler) and which went on to make a profit continuously until 1848. Thanks to discoveries of rich ore seams it became the most productive Freiberg mine of the 19th century.

But even the excavation of the Rothschönberger Stolln, the largest and most important Saxon drainage adit, which drained the entire Freiberg district, could not stop the decline of mining. Because even before the completion of this technical achievement the German Empire introduced the gold standard in 1871, the price of silver dropped rapidly and led to the unprofitability of the entire Ore Mountain silver mining industry. This situation was not altered even by short-term discoveries of rich deposits in various mines nor the state's purchase of all the Freiberg mines and their incorporation into the state-owned enterprise, Oberdirektion der Königlichen Erzbergwerke, founded in 1886. In 1913, the last silver mines closed and the company was disbanded.

Mining in the Ore Mountains was given new life during the First and Second World Wars in order to supply raw materials. The Third Reich also saw the resumption of silver mining. Afterwards the people returned to the manufacture of wooden products and toys, especially in the Eastern Ore Mountains. The clock industry is centred on Glashütte. In the Western Ore Mountains, economic alternatives were offered by the engineering and textile industries.

In 1789 the chemical element uranium was discovered in St. Joachimsthal; then in pitchblende from the same area, radium was discovered by Marie Curie in 1898. In the late 1930s, following the discovery of the nuclear fission, uranium ore became of particular interest for military purposes. After the incorporation of Sudetenland into Germany in 1938 all the uranium production facilities were commandeered for the development of nuclear weapons. After the American atomic bomb was dropped on Japan in 1945, Soviet experts searched for evidence of the German nuclear energy project to support Soviet atomic bomb development. Shortly thereafter, the processing of uranium ore for the Soviet Union began in the Ore Mountains under the code name SAG Wismut, a cover up for the Eastern Bloc's highly secretive uranium mining.[5][17][18]

For the third time in history, thousands of people poured into the Ore Mountains to build a new life. The principal mining areas were located around Johanngeorgenstadt, Schlema and Aue. Uranium ore deposits were also exploited for the Soviet Union in Bohemian Jáchymov (St. Joachimsthal). Its processing was associated with serious health consequences for the miners. In addition a dam burst in 1954 at Lengenfeld at a uranium mining waste lake; 50,000 cubic metres of waste water poured down 4 kilometres into the valley.[19] Until 1991 uranium ore was also mined in Aue-Alberoda and Pöhla.

Mining operations in Freiberg that had begun in 1168 finally ceased in 1968 after 800 years. In Altenberg and Ehrenfriedersdorf tin mining continued to 1991. The smelting of these ores took place mainly in Muldenhütten until the early 1990s. In St. Egidien and Aue there were important nickel smelting sites. In Pöhla in the Western Ore Mountains, during exploratory work for SDAG Wismut new, rich lodes of tin ore were discovered in the 1980s. The test workings of that time are now considered the largest tin finds in Europe. Another well-known place of tin production was Seiffen. The village in the Eastern Ore Mountains has become a leading centre of wood and toy manufacturing. Here, wooden smoking figures, nutcrackers, hand-carved wooden trees (Spanbäume), candle arches, (Schwibbogen), Christmas pyramids and music boxes are made. Up to the last third of the 20th century, Coal was mined near Zwickau until 1978, around Lugau and Oelsnitz until 1971 and in the Döhlen Basin near Freital until 1989.

The mountains that until the late 11th (and early 12th century) were covered in dense forests were almost completely transformed into a cultural landscape by the mining industry and by settlement. The population density is high right up into the upper regions of the mountains. For example, Oberwiesenthal, the highest town in Germany, lies in the Ore Mountains, and neighbouring Boží Dar (German: Gottesgab) on the Czech side, is actually the highest town in Central Europe. Only on the relatively inaccessible, less climatically favourable ridges are there still large, contiguous forests, but since the 18th century these have been managed economically. Due to the high demand for timber by the mining and smelting industries, where it was needed for pit props and fuel, large-scale deforestation took place from the 12th century onwards, and even the forests owned by the nobility could not cover the growing demand for wood. In the 18th century, industries were encouraged to use coal as fuel instead of timber in order to preserve the forests, and this was enforced in the 19th century. In the early 1960s the first signs of forest dieback were seen in the Eastern Ore Mountains near Altenberg and Reitzenhain, after local damage to the forests had become apparent since the 19th century as a result of smelter smoke (Hüttenrauch). The German population of the Bohemian part of the Ore Mountains was expelled in 1945 in accordance with to the Beneš decrees.

Nature

The upper western part of the Ore Mountains, known in German as Erzgebirge, belongs to the Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park. The eastern part, called the Eastern Ore Mountains (Osterzgebirge), is a protected landscape. Further small areas are nature reserves and natural monuments, and are protected by the state.

Nature reserves

- Germany (selection)

- Western Ore Mountains Special Protected Area (SPA Westerzgebirge)

- Valley of the Große Bockau Special Area of Conservation (FFH-Gebiet Tal der Großen Bockau)

- Mountain meadows in the Eastern Ore Mountains major nature conservation project (Naturschutzgroßprojekt Bergwiesen im Osterzgebirge)

- Geisingberg nature reserve, 314.00 ha

- Georgenfelder Hochmoor nature reserve, 12.45 ha

- Fürstenau Heath (Fürstenauer Heide) nature reserve (Black Grouse conservation area near Fürstenau), 7.24 ha

- Kleiner Kranichsee nature reserve, 28.97 ha

- Großer Kranichsee nature reserve, 611.00 ha

- Hermannsdorf Meadows (Hermannsdorfer Wiesen) nature reserve, 185.00 ha

- The Czech Republic (selection)

- NPR Božídarské rašeliniště, 929.57 ha (1965)

- NPR Velké jeřábí jezero, 26.9 ha (1938)

- NPR Velký močál, 50.27 ha (1969)

- NPR Novodomské rašeliniště, 230 ha (1967)

- PR Černý rybník, 32.56 ha (1993)

- PR Malé jeřábí jezero, 6.02 ha (1962)

- PR Ryžovna, 20 ha

Mining and Pollution

Ever since the settlement in mediaeval times, the Ore Mountains were farmed intensively. This led to widespread clearings of the originally dense forest, also to keep up with the enormous need for wood in mining and metallurgy. Mining including the construction of dumps, impoundments, and ditches in many places also directly shaped the scenery and the habitats of plants and animals.

Evidence for local forest dieback due to the smoke from smelting furnaces was first noted the 19th century. In the 20th century, several mountain crests were deforested because of their climatically exposed location. Thus, in recent years, mixed forests are cultivated which are more resistant to weather effects and pests than the traditional monocultures of spruces.

The Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park

Human interventions have created a unique cultural landscape with a large number of typical biotopes which are worthy of protection such as mountain meadows and wetlands. Today, even old mining spoil heaps offer a living environment for a variety of plants and animals. 61% of the area of Ore Mountains/Vogtland Nature Park is covered with woodland. In particular in the western Ore Mountains, huge contiguous woodlands spread all the way to the highest altitudes and are used for forestry. Moreover, in this area several rain water fed bogs are found. Many of these protected areas offer a retreat for rare species with special environmental adaptations such as different species of orchids and gentian, the Eurasian pygmy owl and kingfishers. Some alpine species of plants and animals that have been found at higher altitudes of the Ore mountains are otherwise only known from more distant places in the Sudeten mountains or the Alps. After conditions improved, once displaced species such as Eagle owls and Black storks have returned in the early 21st century.

Economy

The German part of the Ore Mountains is one of the major business locations in Saxony. The region has a high density of industrial operations. Since 2000, the number of industrial workers has risen against the Germany-wide trend by about 20 percent. Typical of the Ore Mountains are mainly small, often owner-managed, businesses.

The economic strengths of the Ore Mountains are mainly in manufacturing. 63 percent of the industrial workforce is employed in the metalworking and electrical industry.

Only of minor importance is the formerly dominant textile and clothing industry (5 percent of industrial net product) and the food industry. The newly established chemical, leather and plastic industries and the industries traditionally based in the Ore Mountains-based – wood, paper, furniture, glass and ceramics works – each contribute about 14 percent of regional net product.

Mining, the essential historical basis of industrial development in the Ore Mountains, currently plays only a minor economic role on the Saxon side of the border. For example, in Hermsdorf/Erzgeb. in the Eastern Ore Mountains, calcite is mined, and near Lengefeld in the Central Ore Mountains, dolomitic marble is extracted. For the first time in two decades, an ore mine was opened in Niederschlag near Oberwiesenthal on 28 October 2010. It is expected that 50,000-130,000 tons of fluorspar per year will be extracted there.

In the Czech part of the Ore Mountains, tourism has gained a certain importance, even though the Krkonoše are more important for domestic tourism. In addition, mining still plays a greater role, particularly coal mining in the southern forelands of the Ore Mountains. Europe's largest deposits of lithium-bearing mica zinnwaldite in Cínovec, a Czech village between town of Dubí and the border with Germany which gave its old German name Zinnwald to the mineral, are expected to be mined starting 2019 (as of June 2017).[20][21]

Tourism

When several Ore Mountain passes were upgraded into chaussees in the 19th century, and the Upper Ore Mountains were accessed by the railway, tourism began to develop. One of the early promoters of tourism in the Ore Mountains was Otto Delitsch. In 1907, a memorial was erected to him in Wildenthal. In many places mountain inns and observation towers were erected on the highest peaks. At that time, skiers used the ridges with their guaranteed snow. Today, steam-worked narrow gauge railways dating to that era, such as the Pressnitz Valley Railway, are popular tourist attractions.

In 1924 the Fichtelberg Cable Car became the first cable car in Germany, and it still takes visitors to the highest mountain in Saxony. The Ridgeway (Kammweg) was one of the first long-distance paths to be established. This once ran from Hainsberg near Asch over the Ore Mountains, Bohemian Switzerland and the Lusatian Mountains to Sněžka in the Krkonoše. Today there is not only a dense network of trails, but also an extensive cross country skiing network and downhill ski slopes for winter sports. The most important ski resort is Oberwiesenthal on the Fichtelberg mountain. And the Ore Mountain/Krušné hory Ski Trail is a German-Czech ski mountaineering trail along the entire Ore Mountain crest.

Based on the historical Silver Road a tourist road was created in 1990 running from Zwickau to Dresden traversing the entire Ore Mountains and linking its main attractions. These include visitor mines, mining trails, technical and local history museums and numerous other smaller attractions, especially the medieval town centres in the old mining towns and its major churches, such as Freiberg Cathedral, St. Anne's Church in Annaberg-Buchholz or St Wolfgang's Church at Schneeberg. On the Bohemian and Saxon sides of the border there are also many castles, built in different architectural styles, which may be visited. One of the best known examples is Augustusburg Castle

In the Advent and Christmas season the Ore Mountains, with its distinct traditions, Christmas markets and miners' parades is also a popular destination for short breaks.

With 960,963 guests staying for 2,937,204 nights in 2007[22] the Ore Mountains and West Saxony is the most important Saxon holiday destination after the cities, and tourism is an important economic factor in the region. Since 2004 the Ore Mountain Tourist Association (Tourismusverband Erzgebirge) has offered the Ore Mountain Card (ErzgebirgsCard) with which over 100 museums, castles, heritage railways and other sights may be visited free of charge.

UNESCO World Heritage Site

In 2019, the following 22 mines or mining complexes were added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region.[3]

| Site | Country | Location | Area ha (acre) |

Buffer Area ha (acre) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dippoldiswalde Medieval Silver Mines | Germany | 50°53′48″N 13°40′26″E | 536.871 | - |

| Altenberg-Zinnwald Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°45′50″N 13°46′13″E | 269.367 | 1,716.705 |

| Lauenstein Administrative Centre | Germany | 50°47′07″N 13°49′23″E | 2.926 | 18.885 |

| Freiberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°55′05″N 13°20′40″E | 624.434 | 2,202.532 |

| Hoher Forst Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°37′10″N 12°34′07″E | 44.799 | 103.604 |

| Schneeberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°35′44″N 12°38′39″E | 218.15 | 670.351 |

| Schindlers Werk Smalt Works | Germany | 50°32′31″N 12°39′30″E | 2.659 | 2.7 |

| Annaberg-Frohnau Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°34′52″N 12°59′33″E | 191.994 | 926.131 |

| Pöhlberg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°34′32″N 13°02′43″E | 118.94 | - |

| Buchholz Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°33′47″N 12°59′20″E | 37.346 | - |

| Marienberg Mining Town | Germany | 50°39′02″N 13°09′47″E | 25.306 | 44.603 |

| Lauta Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°39′50″N 13°08′33″E | 20.592 | - |

| Ehrenfriedersdorf Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°38′35″N 12°58′35″E | 71.148 | 891.575 |

| Grünthal Silver-Copper Liquation Works | Germany | 50°39′01″N 13°22′08″E | 12.917 | 25.294 |

| Eibenstock Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°30′45″N 12°35′57″E | 100.656 | 248.312 |

| Rother Berg Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°31′12″N 12°47′15″E | 4.519 | 38.556 |

| Uranium Mining Landscape | Germany | 50°38′00″N 12°41′08″E | 811.213 | 746.263 |

| Jáchymov Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°22′16″N 12°54′47″E | 738.452 | 637.9 |

| Abertamy – Boží Dar – Horní Blatná – Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°24′23″N 12°50′14″E | 2,608.279 | 3,011.867 |

| The Red Tower of Death | Czech Republic | 50°19′44″N 12°57′12″E | 0.2 | 2.804 |

| Krupka Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°41′6.″N 13°51′19″E | 317.565 | 474.299 |

| Mědník Hill Mining Landscape | Czech Republic | 50°25′27″N 13°06′41″E | 7.724 | 1,255.41 |

Culture

_2006-11-30.jpg)

The culture of the Ore Mountains was shaped mainly by mining that goes back to the Middle Ages. The old saying, coined here, that "everything comes from the mine" (Alles kommt vom Bergwerk her!) refers to many areas of life in the region, from its landscape, to its handicrafts, industry, living traditions and folk art. The visitor may recognise this on his arrival from the normal everyday greeting Glück Auf! that is used in the region.

The Ore Mountains has its own dialect, Erzgebirgisch, which sits on the boundary between Upper German and Central German and is not therefore uniform.

The first important native dialect poet of the Ore Mountains was Christian Gottlob Wild in the early 19th century. At the beginning of the 20th century, Hans Soph, Stephan Dietrich and especially Anton Günther were active; their works have a lasting impact to this day in Ore Mountain songs and writings. Erzgebirgisch songs were later popularised by various local groups. The most famous include the Preßnitzer Musikanten, Geschwister Caldarelli, Zschorlauer Nachtigallen, the Erzgebirgsensemble Aue and Joachim Süß and his Ensemble. Today it is mainly De Randfichten, but also groups like Wind, Sand und Sterne, De Ranzn, De Krippelkiefern, De Erbschleicher and Schluckauf that sing in the Erzgebirgisch dialect.

The Ore Mountains are nationally known for their variety of customs at Advent and Christmas time. This is epitomized by traditional Ore Mountain folk art, in the form of smoking figures, Christmas pyramids, candle arches, nutcrackers, miners' and angels' figures, all of which are used as Christmas decorations. Above all, places in the Upper Ore Mountains decorate their windows during the Christmas season in such a way that they are transformed into a "sea of light". In addition, traditional Christmas mining celebrations such as the Mettenschicht and Hutzenabende draw many visitors and have made the Ore Mountains known as "Christmasland" (Weihnachtsland).

In addition to the Christmas markets and other smaller traditional and modern folk festivals, the Annaberger Kät is the most famous and largest Ore Mountain folk festival. Started in 1520 by Duke George the Bearded, it has been held annually since.

Also interesting is Ore Mountain cuisine, which is simple, but rich in tradition.

In 2019 the region was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List as the Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region.[3]

Gallery

Stürmer mountain

Stürmer mountain Old adit near Johanngeorgenstadt

Old adit near Johanngeorgenstadt- Jáchymov town hall

Klínovec mountain

Klínovec mountain Uranite from the Ore Mountains

Uranite from the Ore Mountains

See also

- Erzgebirgisch, the local German dialect

- List of mountains in the Ore Mountains

- List of regions of Saxony

- Hans Carl von Carlowitz (1645–1714), mining and forestry expert

- Saxon Highlands and Uplands

References

- Also called sometimes the Ore Mountains range, Erz Mountains /ɛərts, ɜːrts/ or the Krušné Mountains /ˈkrʊʃni, -neɪ/ after the German and Czech names respectively.

- "Krušné hory". rozhlas.cz. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Erzgebirge/Krušnohoří Mining Region". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 2019-07-08.

- Elkins, T H (1972). Germany (3rd ed.). London: Chatto & Windus, p. 291. ASIN B0011Z9KJA.

- Heinrich, E. Wm. (1958). Mineralogy and Geology of Radioactive Raw Materials. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc. pp. 283–284.

- Emil Meynen, ed. (1953–1962). Handbuch der naturräumlichen Gliederung Deutschlands. Remagen/Bad Godesberg: Bundesanstalt für Landeskunde.

- Map of natural regions in Saxony Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine at www.umwelt.sachsen.de (pdf, 859 kB)

- Athenaum sive Universitas Boemo-Zinnwaldensis von 1717, published by Peter Schenk.

- Anonymous (1775). Mineralogische Geschichte des Sächsischen Erzgebirges. Hamburg: Carl Ernst Bohn.

- "Deutscher Wetterdienst, Normalperiode 1961–1990". dwd.de. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Novotný, Michal (2004-01-20). "Krušné hory". Český rozhlas Regina. Retrieved 2015-07-07.

- Penhallurick, R.D. (1986). Tin in Antiquity: its Mining and Trade Throughout the Ancient World with Particular Reference to Cornwall. London: The Institute of Metals. ISBN 0-904357-81-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gerrard, S. (2000). The Early British Tin Industry. Stroud: Tempus Publishing. ISBN 0-7524-1452-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lo Schiavo, F. (2003). "The problem of early tin from the point of view of Nuragic Sardinia". In Giumlia-Mair, A.; Lo Schiavo, F. (eds.). The Problem of Early Tin. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 121–132. ISBN 1-84171-564-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pulak, C. (2001). "The cargo of the Uluburun ship and evidence for trade with the Aegean and beyond". In Bonfante, L.; Karageogrhis, V. (eds.). Italy and Cyprus in Antiquity: 1500–450 BC. Nicosia: The Costakis and Leto Severis Foundation. pp. 12–61. ISBN 9963-8102-3-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- National Geographic. June 2002. p. 1. Ask Us.

- Zoellner, Tom (2009). Uranium. New York: Penguin Books. pp. 17–22, 38, 55, 135–142, 161–165, 173–176. ISBN 9780143116721.

- Williams, Susan (2016). Spies in the Congo. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 187. ISBN 9781610396547.

- Peter Diehl: Altstandorte des Uranbergbaus in Sachsen pdf file

- Seidler, Christoph (2 May 2012). "Mining Revival: German Solar Firm Goes Hunting For Lithium". Retrieved 2 April 2018 – via Spiegel Online.

- Editorial, Reuters. "RPT-Miners eye Europe's largest lithium deposit in Czech Republic". reuters.com. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Stat Statistics Office for the Free State of Saxony, Accommodation statistics (including campers)". sachsen.de. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

Further reading

- Harald Häckel, Joachim Kunze: Unser schönes Erzgebirge. 4th edition, Häckel 2001, ISBN 3-9803680-0-9

- Peter Rölke (Hrsg.): Wander- & Naturführer Osterzgebirge, Berg- & Naturverlag Rölke, Dresden 2007, ISBN 978-3-934514-20-1

- Müller, Ralph u.a.: Wander- & Naturführer Westerzgebirge, Berg- & Naturverlag Rölke, Dresden 2002, ISBN 3-934514-11-1

- NN: Kompass Karten: Erzgebirge West, Mitte, Ost. Wander- und Radwanderkarte 1:50.000, GPS kompatibel. Kompass Verlag, 2002, ISBN 3-85491-954-9

- NN: Erzgebirge, Vogtland, Chemnitz. HB Bildatlas, Heft No. 171. 2., akt. Aufl. 2001, ISBN 3-616-06271-3

- Peter Rochhaus: Berühmte Erzgebirger in Daten und Geschichten. Sutton Verlag, Erfurt 2006, ISBN 978-3-86680-020-5

- Siegfried Roßberg: Die Entwicklung des Verkehrswesens im Erzgebirge – Der Kraftverkehr. Bildverlag Böttger, Witzschdorf 2005, ISBN 3-9808250-9-4

- Bernd Wurlitzer: Erzgebirge, Vogtland. Marco Polo Reiseführer. 5., akt. Aufl. Mairs Geographischer Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-8297-0005-9

- Emmermann, Rolf; Tischendorf, Gerhard; Trumbull, Robert B; Möller, Peter (1994): Magmatism and Metallogeny in the Erzgebirge. Geowissenschaften; 12; 337–341; doi:10.2312/GEOWISSENSCHAFTEN.1994.12.337

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ore Mountains. |

- Ore Mountains article at www.britannica.com

- UNESCO World Heritage Project "Montanregion Erzgebirge"

- Ore mountains tourist website for the Czech Ore Mountains

- Animation of geological formation of the Ore Mountains

- http://www.westerzgebirge.com/htm/erzgebirge-personen.htm

-Deutschland.png)

-Deutschland.png)

-Deutschland.png)

-Deutschland.png)

.jpg)

.jpg)