Music box

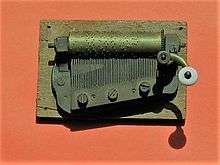

A music box or musical box is an automatic musical instrument in a box which produces musical notes by using a set of pins placed on a revolving cylinder or disc to pluck the tuned teeth (or lamellae) of a steel comb. The earliest known mechanical musical instruments date back to 9th-century Baghdad. In Flanders, in the early 13th century, a bell ringer invented a cylinder with pins which operate cams, which then hit the bells. (See below.) The popular device best known today as a "music box" developed from musical snuff boxes of the 18th century and were originally called carillons à musique (French for "chimes of music"). Some of the more complex boxes also contain a tiny drum and/or bells in addition to the metal comb.

.jpg)

History

The original snuff boxes were tiny containers which could fit into a gentleman's waistcoat pocket. The music boxes could have any size from that of a hat box to a large piece of furniture, but most were tabletop specimens. They were usually powered by clockwork and originally produced by artisan watchmakers. For most of the 19th century, the bulk of music box production was concentrated in Switzerland, building upon a strong watchmaking tradition. The first music box factory was opened there in 1815 by Jérémie Recordon and Samuel Junod. There were also a few manufacturers in Bohemia and Germany. By the end of the 19th century, some of the European makers had opened factories in the United States.

The cylinders were normally made of metal and powered by a spring. In some of the costlier models, the cylinders could be removed to change melodies, thanks to an invention by Paillard in 1862, which was perfected by Metert of Geneva in 1879. In some exceptional models, there were four springs, to provide continuous play for up to three hours.

The very first boxes at the end of the 18th century made use of metal disks. The switchover to cylinders seems to have been completed after the Napoleonic wars. In the last decades of the 19th century, however, mass-produced models such as the Polyphon and others all made use of interchangeable metal disks instead of cylinders. The cylinder-based machines rapidly became a minority.

The term "music box" is also applied to clockwork devices where a removable metal disk or cylinder was used only in a "programming" function without producing the sounds directly by means of pins and a comb. Instead, the cylinder (or disk) worked by actuating bellows and levers which fed and opened pneumatic valves which activated a modified wind instrument or plucked the chords on a modified string instrument. Some devices could do both at the same time and were often combinations of player pianos and music boxes, such as the Orchestrion.

There were many variations of large music machines, usually built for the affluent of the pre-phonograph 19th century.

The Symphonium company started business in 1885 as the first manufacturers of disc-playing music boxes.[1] Two of the founders of the company, Gustave Brachhausen and Paul Riessner, left to set up a new firm, Polyphon, in direct competition with their original business and their third partner, Oscar Paul Lochmann.[1] Following the establishment of the Original Musikwerke Paul Lochmann in 1900, the founding Symphonion business continued until 1909.[1]

According to the Victoria Museums in Australia, “The Symphonion is notable for the enormous diversity of types, styles and models produced... No other disc-playing musical box exists in so many varieties. The company also pioneered the use of electric motors...the first model fitted with an electric motor being advertised in 1900. The company moved into the piano-orchestrion business and made both disc-operated and barrel-playing models, player-pianos and phonographs.“

Meanwhile, Polyphon expanded to America. where Brachhausen established the Regina Company. Regina was a spectacular success (see Wikipedia article). It eventually reinvented itself as a maker of vacuums and steam cleaners.

In the heyday of the music box, some variations were as tall as a grandfather clock and all used interchangeable large disks to play different sets of tunes. These were spring-wound and driven and both had a bell-like sound. The machines were often made in England, Italy, and the US, with additional disks made in Switzerland, Austria, and Prussia. Early "juke-box" pay versions of them existed in public places. Marsh's free Museum and curio shop in Long Beach, Washington (US) has several still-working versions of them on public display. The Musical Museum, Brentford, London has a number of machines.[2] The Morris Museum in Morristown, New Jersey, USA has a notable collection, including interactive exhibits. In addition to video and audio footage of each piece, the actual instruments are demonstrated for the public daily on a rotational basis.[3]

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, most music boxes were gradually replaced by player pianos, which were louder and more versatile and melodious, when kept tuned, and by the smaller gramophones which had the advantage of playing back voices. Regina produced combinations of these devices. Escalating labour costs increased the price and further reduced volume. Now modern automation is helping to bring music box prices back down.

Collectors prize surviving music boxes from the 19th century and the early 20th century as well as new music boxes being made today in several countries (see "Evolving Box Production", below). Inexpensive, small windup music box movements (including the cylinder and comb and the spring) that add a bit of music to mass-produced jewellery boxes and novelty items are now produced in countries with low labour costs.

Many kinds of music box movements are available to the home craft person, locally or through online retailers. A wide range of recordings and videos of historic music boxes is available on the web.

Timeline

9th century: In Baghdad, Iraq, the Banū Mūsā brothers, a trio of Persian inventors, produced "the earliest known mechanical musical instrument", in this case a hydropowered organ which played interchangeable cylinders automatically, which they described in their Book of Ingenious Devices. According to Charles B. Fowler, this "cylinder with raised pins on the surface remained the basic device to produce and reproduce music mechanically until the second half of the nineteenth century."[4]

Early 13th century: In Flanders, an ingenious bell ringer invents a cylinder with pins which operates cams, which then hit the bells.[4]

1598: Flemish clockmaker Nicholas Vallin produces a wall-mounted clock which has a pinned barrel playing on multiple tuned bells mounted in the superstructure. The barrel can be programmed, as the pins can be separately placed in the holes provided on the surface of the barrel.[5]

1665: Ahasuerus Fromanteel in London makes a table clock which has quarter striking and musical work on multiple bells operated by a pinned barrel. These barrels can be changed for those playing different tunes.[6]

1760s: Watches are made in London by makers such as James Cox which have a pinned drum playing popular tunes on several small bells arranged in a stack.

1772: A watch is made by one Ransonet at Nancy, France which has a pinned drum playing music not on bells but on tuned steel prongs arranged vertically.[7]

1780: The mechanical singing bird is invented by the Jaquet-Droz brothers, clockmakers from La Chaux-de-Fonds. In 1848, the manufacturing of the singing birds is improved by Blaise Bontems in his Parisian workshop, to the point where it has remained unchanged to this day. Barrel organs become more popular.

1796: Antoine Favre-Salomon, a clockmaker from Geneva replaces the stack of bells by a comb with multiple pre-tuned metallic notes in order to reduce space. Together with a horizontally placed pinned barrel, this produces more varied and complex sounds. One of these first music boxes is now displayed at the Shanghai Gallery of Antique Music Boxes and Automata in Pudong's Oriental Art Center.[8] Numerous musical objects are produced in greater quantities in Geneva by several makers.

1800: Isaac Daniel Piguet in Geneva produces repeating musical watches with a pinned horizontal disc operating radially arranged tuned steel teeth.

1811: The first music boxes are produced in Sainte-Croix; an industry which surpasses the watchmaking and lace industries, and rapidly brings renown to the town. At this time, the musical-box industry represents 10% of Switzerland's export.

1865: Charles Reuge, a watchmaker from the Val-de-Travers, settles in Sainte-Croix. He is one of many artisans making pocket watches with musical movements of the traditional calibre.

1870: A German inventor creates a music box with discs, therefore allowing an easier and more frequent change of tunes. It is also the golden years of automata. Already known in Egypt, they will be improved to become real works of art.

1877: Thomas Edison invents the phonograph, which has important consequences for the musical-box industry, especially around the end of the century.

1892: Gustave Brachhausen, who had been involved with the manufacturer of Polyphon disk music boxes in Germany, sails for America to establish the Regina Music Box Company in New Jersey. Regina, whose boxes are renowned among collectors for their tone, becomes a success and some 100,000 are sold before sales cease in 1921.

Early 20th century: The invention of the phonograph, the First World War and the economic crisis in the '20s bring down Sainte-Croix's main industry and make the luxury music box completely disappear.

Between the two world wars most of the Swiss companies converted to the manufacture of other products requiring precise mechanical parts. Some went back to making watches, others were eventually responsible for the famous Bolex movie cameras and the Hermes typewriters. Some simply sold out to Reuge.

Located near Lake Neuchâtel, Reuge is one of the last of the Swiss survivors making music boxes of all sizes and shapes, with or without automatons in a modern style with clear acrylic sides to see the mechanical operation. They have in a sense branched out widely from their original cylinder offerings since they also offered traditional-looking music boxes with removable metal disks for around 1,000 euros, with each disk costing in the neighborhood of 14 euros. The higher range boxes with removable cylinders and small assorted tables made of fine woods can cost up to 34,000 euros and about an equivalent number of US dollars. They also sell several models of clear acrylic paperweights with a music box movement inside, for a minimum of about 250 euros. They have, however, discontinued the smaller movements. Old Reuge music boxes are worth thousands of dollars but even so, cannot be compared to the fabulously large and highly complex music boxes which were produced in nineteenth-century Switzerland by legendary makers such as Nicole Frères or Paillard. Since approximatively 2007 Reuge developed a strong business in the world of "bespoke" customized pieces for leaders in business and politics.

Nidec Sankyo in Japan started up in the aftermath of World War II, using the latest in automation. Modern production methods resulted in reasonable prices, producing company growth. Sankyo started with small movements, introduced 50-note movements by the late 1970s, and in 2006 is producing disc boxes playing discs as large as 16" (with two 80-note combs and reminiscent of the "Mira") and are also working on a dual-cylinder 100-note movement. Sankyo now offers a wide variety of music boxes in Japan, and supplies movements to many other manufacturers and distributors. Some of these sell them retail (even online) to hobbyists for as low as 3 euros each. Sankyo Seiki bills itself as the biggest manufacturer of music boxes in the world and advertises that it controls 50% of the market. Recently, it has started selling licences for its musical-box tunes to cellular phone companies, for use as ring tones. The company is an industrial concern which also makes magnetic and hologram card readers, appliance components, industrial robots and miniature motors of all kinds.

The Porter Music Box company of Vermont produces steel disc music boxes in several formats. They offer clockwork, spring-wound models as well as electric ones. They stand out by their continuing production of discs, with a selection of about a thousand tunes. The discs can also be played on many antique music boxes bearing the Polyphon and Regina brand names.

The small 18-note musical movements are now being made almost exclusively in countries with low labour costs such as China and Taiwan. Many of these productions are used in mobiles, children's musical toys, and jewellery boxes.

In March 2016, the band Wintergatan released a video of their homemade Marble Machine which took 14 months to make and played in any key using a 3,000-piece wooden construction fueled by 2,000 marbles. Band member Martin Molin used a hand crank to mobilize the marbles, which then created various noises on a vibraphone and other installed musical elements.[9]

In 2019, Tevofy Technology Ltd., based in Taiwan, released the first app-controlled mechanical music box called Muro Box, which stands for Music Robot in a Box. Unlike traditional music box, people do not need to punch holes to compose songs on a paper-strip music box. Also, there is no minimum order for making customized music box movement to play a selected song. Muro Box gives more freedom in composing songs and choosing songs to play on a music box.[10]

Coin-operated models

In Switzerland, coin-operated music boxes, usually capable of playing several tunes, were installed in places such as train stations and amusement parks. Some of the models had a mechanism for automatically changing the metal disks. These were, in a sense, the precursors to jukebox. However, they soon disappeared from their intended venues and were displaced by the jukebox, which could produce a greater variety of sounds and full songs rather than warped fragments.

Because most of the coin-operated music boxes were built for rough treatment (such as slapping and kicking by a customer), many of these large models have survived into the 21st century, despite their relatively low production quantities. They are sought by collectors who have the space for their large or very large cabinets.

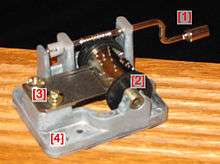

Parts

- The bedplate is the relatively heavy metal foundation on which all the other pieces are fastened, usually by screws.

- The ratchet lever or the windup key is used to put the spring motor under tension, which is to wind it up.

- The spring motor or motors (two or more can be used to make playing times longer) give anywhere from a few minutes to an hour or more of playing time.

- The comb is a flat piece of metal with dozens or even hundreds of tuned teeth, or 'reeds', of different lengths.

- The cylinder is the programming object, a metallic version of a punched card which instead of having holes to express a program, is studded with tiny pins at the correct spacing to produce music by displacing the teeth of the comb at the correct time. The tines of the comb 'ring', or sound, as they slip off the pins. The disc in a disc music box plays this function, with pins perpendicular to the plane surface.

- Multiple-tune cylinders have more than one set of pins intertwined on the same cylinder, with, for example, the B pins for a second song lying halfway between the B and C pins of the first song, etc. Offsetting the cylinder slightly relative to the comb brings the different set of pins into contact with the teeth, thereby playing an alternate piece of music. Many modern music boxes will have as many as four sets of pins intertwined, with a mechanism automatically shifting the cylinder from one song or movement to the next.

Repertoire

In 1974–75, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen composed Tierkreis, a set of twelve pieces on the signs of the zodiac, for twelve music boxes.[11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

See also

- Barrel organ

- Cuckoo clock

- Graphophone

- Musical clock

- Player piano

- Singing bird box

- Shanghai Gallery of Antique Music Boxes and Automata

References

- "Hose, K. (2009) A Brief History of the Symphonion Company in Museums Victoria Collections".

- "musicalmuseum.co.uk". Archived from the original on 2011-04-26. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- morrismuseum.org

- Fowler, Charles B. (October 1967), "The Museum of Music: A History of Mechanical Instruments", Music Educators Journal, MENC_ The National Association for Music Education, 54 (2): 45–49, doi:10.2307/3391092, JSTOR 3391092. Citation on p. 45.

- In the Collections of the British Museum (M.L. Antiquities Dept. Ilbert collection)

- Horological Masterworks Exhibition AHS 2003 Catalogue No.14

- Sotheby's Auction Masterpieces from the Time Museum June 19, 2002 Lot 73

- en.shoac.com.cn, "Antique Music Box Gallery", accessed 18 Dec 2014.

- "Wintergatan Marble Machine – A Feat of Both Music and Engineering", indiebandguru.com, Retrieved March 3, 2016

- “Muro Box Story.” Muro Box, 26 June 2019, murobox.com/en/story/index.html.

- Peter Andraschke, "Kompositorische Tendenzen bei Karlheinz Stockhausen seit 1965", in Zur Neuen Einfachheit in der Musik, Studien zur Wertungsforschung 14, edited by Otto Kolleritsch, 126–43 (Vienna and Graz: Universal Edition [for the Institut für Wertungsforschung an der Hochschule für Musik und darstellende Kunst in Graz], 1981). ISBN 3-7024-0153-9.

- Giuliano d'Angiolini, "Tierkreis, oeuvre pour instrument mélodique et/ou harmonique: un tournant dans le parcours musical de Stockhausen", Analyse Musicale (1989, 1er trimestre): 68–73.

- Hermann Conen, Formel-Komposition: Zu Karlheinz Stockhausens Musik der siebziger Jahre, Kölner Schriften zur Neuen Musik 1, edited by Johannes Fritsch and Dietrich Kämper. (Mainz: Schott's Söhne, 1991). ISBN 3-7957-1890-2.

- Wilfried Gruhn, "'Neue Einfachheit'? Zu Karlheinz Stockhausens Melodien des Tierkreis", in Reflexionen uber Musik heute: Texte und Analysen, edited by Wilfried Gruhn, 185–202 (Mainz, London, New York, and Tokyo: B. Schott's Söhne, 1981. ISBN 3-7957-2648-4.

- Jerome Kohl, "The Evolution of Macro- and Micro-Time Relations in Stockhausen’s Recent Music", Perspectives of New Music 22 (1983–84): 147–85, citation on 148.

- Michael Kurtz, Stockhausen: A Biography, translated by Richard Toop (London and Boston: Faber and Faber, 1992). ISBN 0-571-14323-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-571-17146-X (pbk).

- Gallus Oberholzer, "Karlheinz Stockhausen komponierte 12 Melodien speziell für Spieldosen", Das mechanische Musikinstrument: Journal der Gesellschaft für selbstspielende Musikinstrumente 12, no. 46 (December 1988): 49.

- Christel Stockhausen, "Stockhausens Tierkreis: Einführung und Hinweise zur praktischen Aufführung" Melos 45 / Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 139 (July–August 1978): 283–87.

Further reading

- Bahl, Gilbert. Music Boxes: The Collector's Guide to Selecting, Restoring and Enjoying New and Vintage Music Boxes. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Running Press, 1993.

- Bowers, Q. David. Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments. ISBN 0-911572-08-2. Lanham, Maryland: Vestal Press, Inc., 1972.

- Diagram Group. Musical Instruments of the World. New York: Facts on File, 1976.

- Ganske, Sharon. Making Marvelous Music Boxes. New York: Sterling Publishing Company, 1997.

- Greenhow, Jean. Making Musical Miniatures. London: B T Batsford, 1979.

- Hoke, Helen, and John Hoke. Music Boxes, Their Lore and Lure. New York: Hawthorn Books, 1957.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. (1973). Clockwork Music. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-789004-8.

- Ord-Hume, Arthur W. J. G. The Musical Box: A Guide for Collectors. ISBN 0-88740-764-1. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 1995.

- Reblitz, Arthur A. The Golden Age of Automatic Musical Instruments. ISBN 0-9705951-0-7. Woodsville, NH: Mechanical Music Press, 2001.

- Reblitz, Arthur A., Q. David Bowers. Treasures of Mechanical Music. ISBN 0-911572-20-1. New York: The Vestal Press, 1981.

- Sadie, Stanley. ed. Musical Box. The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. ISBN 1-56159-174-2. MacMillan. 1980. Vol 12. P. 814.

- Smithsonian Institution. History of Music Machines. ISBN 0-87749-755-9. New York: Drake Publishers, 1975.

- Templeton, Alec, as told to Rachael Bail Baumel. Alec Templeton's Music Boxes. New York: Wilfred Funk, 1958.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Musical boxes. |

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Performance of Listen Thing and Pandora's Secret on a punched paper-tape controlled music box (video)

- Musical Box Society International Glossary of Terms

- Music Box Maniacs – a website dedicated to paper strip punch card music boxes

- Muro box - the first app-controlled music box

Audio of historical music boxes

- Polyphon Music Box, made app. 1850

- Mira Music Box – Sammy 1903

- Mechanical Music Box – Auld Lang Syne

- Mechanical Music from Phonogrammarchiv of the Austrian Academy of Sciences

- LP vinyl record: "The Concert Regina Music Box and the Symphonium" (1977, Nostalgia Repertoire Records – Sonic Arts Corporation, 665 Harrison Street, San Francisco Ca. 94107, Curator: Leo de Gar Kulka, Record No. RR 4771 Stereo.)