Fault block

Fault blocks are very large blocks of rock, sometimes hundreds of kilometres in extent, created by tectonic and localized stresses in Earth's crust. Large areas of bedrock are broken up into blocks by faults. Blocks are characterized by relatively uniform lithology. The largest of these fault blocks are called crustal blocks. Large crustal blocks broken off from tectonic plates are called terranes.[1] Those terranes which are the full thickness of the lithosphere are called microplates. Continent-sized blocks are called variously microcontinents, continental ribbons, H-blocks, extensional allochthons and outer highs.[2]

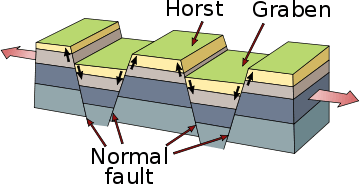

Because most stresses relate to the tectonic activity of moving plates, most motion between blocks is horizontal, that is parallel to the Earth's crust by strike-slip faults. However vertical movement of blocks produces much more dramatic results. Landforms (mountains, hills, ridges, lakes, valleys, etc.) are sometimes formed when the faults have a large vertical displacement. Adjacent raised blocks (horsts) and down-dropped blocks (grabens) can form high escarpments. Often the movement of these blocks is accompanied by tilting, due to compaction or stretching of the crust at that point.

Fault-block mountains

Fault-block mountains often result from rifting, an indicator of extensional tectonics. These can be small or form extensive rift valley systems, such as the East African Rift zone. Death Valley in California is a smaller example. There are two main types of block mountains; uplifted blocks between two faults and tilted blocks mainly controlled by one fault.

Lifted type block mountains have two steep sides exposing both sides scarps, leading to the horst and graben terrain seen in various parts of Europe including the Upper Rhine valley, a graben between two horsts - the Vosges mountains (in France) and the Black Forest (in Germany), and also the Rila - Rhodope Massif in Bulgaria, Southeast Europe, including the well defined horsts of Belasitsa (linear horst), Rila mountain (vaulted domed shaped horst) and Pirin mountain - a horst forming a massive anticline situated between the complex graben valleys of Struma and that of Mesta.[3][4][5]

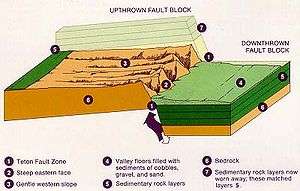

Tilted type block mountains have one gently sloping side and one steep side with an exposed scarp, and are common in the Basin and Range region of the western United States.

Example of graben is the basin of the Narmada River in India, between the Vindhya and Satpura horsts.

See also

- Orogeny – The formation of mountain ranges

Notes

- A crustal block may or may not also comprise a tectonostratigraphic terrane that has a specific geologic definition. Bulter, Robert F. (1992) "Chapter 11: Applications to Regional Tectonics" Paleomagnetism: Magnetic Domains to Geologic Terranes Blackwell, pp. 205–223, page 205, archived here by Internet Archive on 26 October 2004

- Péron-Pinvidic1, Gwenn and Manatschal, Gianreto (2010). "From microcontinents to extensional allochthons: witnesses of how continents rift and break apart?". Petroleum Geoscience. 16 (3): 189–197. doi:10.1144/1354-079309-903.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) page 189

- Geographic Dictionary of Bulgaria 1980, p. 368

- Dimitrova & al 2004, p. 53

- Donchev & Karakashev 2004, pp. 128–129

References

- Plummer, Charles, David McGeary, and Diane Carlson. Physical Geology 8th ed. McGraw-Hill, Boston, 1999.

- Monroe, James S., and Reed Wicander. The Changing Earth: Exploring Geology and Evolution. 2nd educational Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 1997. ISBN 0-314-09577-2 (pp. 234,-8)