Mirdasid dynasty

The Mirdasid dynasty (Arabic: المرداسيون) was an Arab dynasty that controlled the Emirate of Aleppo more or less continuously from 1024 until 1080.

Mirdasid dynasty مرداسيون | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1024–1080 | |||||||||

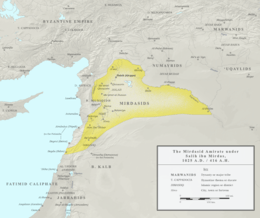

Map of the Mirdasid emirate at its zenith during the rule of Salih ibn Mirdas in 1025 | |||||||||

| Capital | Aleppo | ||||||||

| Common languages | Arabic | ||||||||

| Religion | Shia Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Emirate | ||||||||

| Emir | |||||||||

• 1024–1029 | Salih ibn Mirdas | ||||||||

• 1029–1038 | Shibl al-Dawla Nasr | ||||||||

• 1042–1062 | Mu'izz al-Dawla Thimal | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• | ᵿ̃ɵ | ||||||||

• Established | 1024 | ||||||||

• | ̣ | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 1080 | ||||||||

| Currency | Dirham, dinar | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arab Empires

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

East Africa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

General description

The Mirdasids were members of the Banu Kilab,[1] an Arab tribe that had been present in northern Syria for several centuries. Like the other Arab tribes of the region, the Mirdasids were Shi'a Muslims. Such Arab tribes were susceptible to the propaganda of the Qarmatians, who denounced the wealth of the urban Sunni population. As a result, they were given to Shia sympathies.[2] However, as a result of the expansion of the Seljuk Turks into the area they were constrained to convert to Sunni Islam under Rashid al-Dawla Mahmud.

Unlike other Arab tribes of Syrian province that managed to establish their autonomy or independence in the late 10th/early 11th centuries, the Mirdasids focused their energies on urban development. As a result, Aleppo prospered during their reign. The Mirdasids demonstrated a high degree of tolerance to Christians, favoring Christian merchants in their territories and employing several as viziers. This policy, no doubt influenced by comparatively good relations with the Christian Byzantine Empire, often upset the Muslim population.

The early history of the Mirdasid dynasty is characterized by constant pressure from both the Byzantines and the Fatimids of Egypt. By mixing diplomacy (the Mirdasids were vassals of both the Byzantines and Fatimids several times) and military force, the Mirdasids were able to survive against these two powers.

Militarily, the Mirdasids had the advantage of light Arab cavalry, and several Arab groups in the region, such as the Numayrids of Harran and their own Kilabi brethren, provided valuable assistance. Later on, the Seljuks supplanted the Byzantines and Fatimids as their primary antagonist; the Turks' light cavalry was superior to their own and the Mirdasids had a much more difficult time dealing with them. The Mirdasids had resorted to recruiting Turkic mercenaries into their armies, although this caused its own problems, as the Turks began to acquire an increased role in the government.

List of Mirdasid emirs

| Royal title | Name | Reign start | Reign end | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asad al-Dawla | Salih ibn Mirdas | 18 January 1025[3] | 12 May 1029[3] | |

| Shibl al-Dawla | Nasr ibn Salih | May 1029[3] | May 1038[5] |

|

| Mu'izz al-Dawla | Thimal ibn Salih | February 1042[5] | 1057[6] |

|

| Rashid al-Dawla | Mahmud ibn Nasr[7] | July/August 1060[7] | April 1061[7] | |

| Mu'izz al-Dawla | Thimal ibn Salih | April 1061[7] | 1062[7] | |

| Asad al-Dawla | Atiyya ibn Salih | 1062[7] | August 1065[7] | |

| Rashid al-Dawla | Mahmud ibn Nasr | August 1065 | 1074/75 | |

| Jalal al-Dawla | Nasr ibn Mahmud | 1074/75[8] | 1075[8] | |

| Sabiq ibn Mahmud | 1075/1076[8] | June 1080[8] |

Historical overview

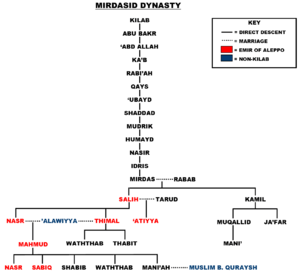

After the overthrow of the Hamdanids in 1004, Aleppo had been ruled by several princes nominally subordinate to the Fatimids. It was from these individuals that Salih ibn Mirdas took the town in 1024.[1] When he died fighting the Fatimids five years later, his two sons Shibl al-Daula Nasr and Mu'izz al-Daula Thimal succeeded him, although Nasr quickly became sole amir. Despite a victory over the Byzantines in Azaz in 1030,[1] in the next year he became a Byzantine vassal. Later he transferred his allegiance to the Fatimids. However, the Fatimid governor of Damascus, Anushtakin al-Dizbari, killed Nasr in battle and took Aleppo 1038.

Nasr's brother Thimal managed to recover Aleppo in 1042 and eventually made peace with the Fatimids. He was a vassal of both the Byzantine Emperor and Fatimid Caliph. Troubles with the Kilab, however, caused him to give up Aleppo to the Fatimids in exchange for several coastal towns. The Kilab threw their support behind Thimal's nephew Rashid al-Daula Mahmud, who took Aleppo in 1060. Thimal returned and in 1061 regained Aleppo from Mahmud, but died a year later.

After Thimal's death a succession dispute emerged between Mahmud and Thimal's brother 'Atiyya ibn Salih, leading to a split in the Mirdasid domains. Mahmud controlled the western half, while 'Atiyya controlled the east. In order to gain an edge over Mahmud, 'Atiyya recruited a band of Turks, but they later defected to Mahmud, forcing 'Atiyya to give up Aleppo in 1065.

The Turks began moving into northern Syria in greater numbers, forcing Mahmud to convert to Sunni Islam and become a vassal of the Seljuk sultan. Mahmud's death in 1075, followed by that of his son and successor Nasr ibn Mahmud in 1076, resulted in Nasr's brother Sabiq ibn Mahmud becoming amir. Conflicts between him and members of his family, along with several different Turkish groups, left the Mirdasid domains devastated, and in 1080, prompted by Sabiq, the Uqailid Sharaf al-Daula Muslim took over Aleppo. The Mirdasids maintained a level of influence in the region after the loss of Aleppo, and attempted to stem the advance of the First Crusade.

Kurdish offshoot

According to the Sharafnama,[9] the Kurdish Mirdasi dynasty, ruling Eğil, Palu and Çermik, took its name from the Mirdasids. Part of the Mirdasids had fled to this region after Salih ibn Mirdas had been killed in 1029. The ruling dynasty allegedly commenced in the early 11th century, when a mystic by the name of Pir Mansour travelled from Hakkari to the village of Pîran, close to the fortress of Egil. He attained widespread fame among the local Kurds and Mirdasids, and his son, Pir Bedir took the fortress of Egil by force and initiated the dynasty's rule over the region.[10]

See also

- Banu 'Amir

- Jarrahids

- Jarwanid dynasty

- Kalbids

- List of Shi'a Muslims dynasties

- Uqailids

- Usfurids

References

- Burns, Ross (2013). Aleppo, A History. Routledge. p. 99. ISBN 9780415737210.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 115.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 117.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 116.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 118.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 119.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 120.

- Bianquis 1993, p. 121.

- Bedlîsî, Şerefxanê (2014). Şerefname: Dîroka Kurdistanê. Translated by Avci, Z. Viranşehir: Azad. ISBN 978-605-64041-8-4.

- Minorsky, Vladimir (1978). The Turks, Iran, and the Caucasus in the Middle Ages. London: Variorum Prints. ISBN 0-86078-028-7.

Further reading

- Bianquis, Thierry (1993). "Mirdās, Banū or Mirdāsids". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Pellat, Ch. (eds.). The Encyclopaedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume VII: Mif–Naz. Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 115–123. ISBN 90-04-09419-9.

- Heidemann, Stefan (2002). Die Renaissance der Städte in Nordsyrien und Nordmesopotamien: Städtische Entwicklung und wirtschaftliche Bedingungen in ar-Raqqa und Harran von der Zeit der beduinischen Vorherrschaft bis zu den Seldschuken. Islamic History and Civilization. Studies and Texts (in German). 40. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-12274-5.