Norman Wilkinson (artist)

Norman Wilkinson CBE RI (24 November 1878 – 30 May 1971) was a British artist who usually worked in oils, watercolors and drypoint. He was primarily a marine painter, but also an illustrator, poster artist, and wartime camoufleur. Wilkinson invented dazzle painting to protect merchant shipping during the First World War.

Norman Wilkinson | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Wilkinson in front of his painting with a model demonstrating one of his dazzle camouflage designs | |

| Born | 24 November 1878 Cambridge, England |

| Died | 30 May 1971 (aged 92) United Kingdom |

| Occupation | Artist |

Background

Wilkinson was born in Cambridge, England, and attended school at Berkhamsted School in Hertfordshire and at St. Paul's Cathedral Choir School in London. His early artistic training occurred in the vicinity of Portsmouth and Cornwall, and at Southsea School of Art, where he was later a teacher as well. He also studied with seascape painter Louis Grier. While aged 21, he studied academic figure painting in Paris, but by then he was already interested in maritime subject matter.[1]

Illustration career

Wilkinson's career in illustration began in 1898, when his work was first accepted by The Illustrated London News, for which he then continued to work for many years, as well as for the Illustrated Mail. Throughout his life, he was a prolific poster artist, designing for the London and North Western Railway, the Southern Railway and the London Midland and Scottish Railway.[1][2] It was mostly owing to his fascination with the sea that he travelled extensively to such locations as Spain, Germany, Italy, Malta, Greece, Aden, the Bahamas, the United States, Canada and Brazil. He also competed in the art competitions at the 1928 and 1948 Summer Olympics.[3]

First World War camouflage

During the First World War, while serving in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, he was assigned to submarine patrols in the Dardanelles, Gallipoli and Gibraltar, and, beginning in 1917, to a minesweeping operation at HMNB Devonport. In April 1917, German submarines (called U-boats) achieved unprecedented success in torpedo attacks on British ships, sinking nearly eight per day. In his autobiography, Wilkinson remembers the moment when, in a flash of insight, he arrived at what he thought would be a way to respond to the submarine threat.[4] He decided that, since it was all but impossible to hide a ship on the ocean (if nothing else, the smoke from its smokestacks would give it away), a far more productive question would be: how can a ship be made to be more difficult to aim at from a distance through a periscope? In his own words, he decided that a ship should be painted "not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading".[4]

After initial testing, Wilkinson's plan was adopted by the British Admiralty, and he was placed in charge of a naval camouflage unit, housed in basement studios at the Royal Academy of Arts. There, he and about two dozen associate artists and art students (camoufleurs, model makers, and construction plan preparators) devised dazzle camouflage schemes, applied them to miniature models, tested the models (using experienced sea observers), and prepared construction diagrams. These were used by other artists at the docks (one of whom was Vorticist artist Edward Wadsworth) in painting the actual ships. Wilkinson was assigned to Washington, D.C. for a month in early 1918, where he served as a consultant to the U.S. Navy, in connection with its establishment of a comparable unit (headed by Harold Van Buskirk, Everett Warner, and Loyd A. Jones).[5][6][7][8]

After the war, there was some contention about who had originated dazzle painting. When Wilkinson applied for credit to the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors, he was challenged by several others, especially the zoologist John Graham Kerr who had developed a disruptive camouflage paint scheme earlier in the war.[9] However, at the end of a legal procedure, Wilkinson was formally declared the inventor of dazzle camouflage, and awarded monetary compensation.[10]

Second World War camouflage

During the Second World War, Wilkinson was again assigned to camouflage, not in dazzle-painting ships (which had fallen out of favour) but with the British Air Ministry, where his primary responsibility was the concealment of airfields.[11] He also travelled extensively to sketch and record the work of the Royal Navy, the Merchant Navy and Coastal Command throughout the war. An exhibition of 52 of the resulting paintings, The War at Sea, was shown at the National Gallery in September 1944. It included nine paintings of the D-Day landings, which Wilkinson had witnessed from HMS Jervis, plus naval actions such as the sinking of the Bismarck. The exhibition toured Australia and New Zealand in 1945 and 1946. The War Artists' Advisory Committee bought one painting from Wilkinson; he donated the other 51 paintings to the Committee.[12]

Awards and honours

Wilkinson was elected to the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours (RI) in 1906, and became its President in 1936, an office he held until 1963. He was elected Honourable Marine Painter to the Royal Yacht Squadron in 1919. He was a member of the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Royal Society of Marine Artists, and the Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the 1918 New Year Honours, and a Commander of the Order (CBE) in the 1948 Birthday Honours.[1]

Exhibits and collections

.jpg)

Wilkinson's marine paintings are displayed in the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich, the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, the Fine Art Society, the Glasgow Institute of the Fine Arts, the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, the Abbey Gallery, the Royal Society of Artists, Birmingham, and the Beaux Arts Gallery. The Imperial War Museum has over 30 ship models painted in a variety of dazzle schemes by Wilkinson, mostly from 1917.[13]

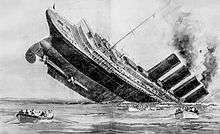

He created a painting titled Plymouth Harbour for the first class smoking room of the RMS Titanic. The painting perished when the ship went down. He also created a comparable painting titled The Approach to the New World, which hung in the same location on the Titanic's sister ship, the RMS Olympic. This latter work is seen in the 1958 film A Night to Remember aboard the Titanic, due to the loss of Plymouth Harbour. A full-sized reproduction of Plymouth Harbour was later produced by Wilkinson's son Rodney based on a miniature copy found among his father's documents. This version appears in the 1997 film Titanic.[14]

References

- "Mr. Norman Wilkinson". The Times. The Times Digital Archive. 1 June 1971. p. 12.

- Cole, Beverley; Durack, Richard; National Railway Museum (1992). Railway Posters 1923-1947: From the Collection of the National Railway Museum, York. Laurence King Publishing. p. 58. ISBN 9781856690140.

- Gjerde, Arild; Jeroen Heijmans; Bill Mallon; Hilary Evans (October 2017). "Norman Wilkinson Bio, Stats, and Results". Olympics. Sports Reference. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- Wilkinson, 1969. p. 79

- Hartcup, 1980.

- Behrens, 2002.

- Behrens, 2009.

- Wilkinson, 1969.

- Hugh Murphy and Martin Bellamy, "The Dazzling Zoologist: John Graham Kerr and the Early Development of Ship Camouflage" in The Northern Mariner XIX No 2 (April 2009), p. 177

- Wilkinson, 1969. pp. 94–95

- Goodden, 2007.

- Foss, Brian (2007). War paint: Art, War, State and Identity in Britain, 1939–1945. Yale University Press. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-300-10890-3.

- Imperial War Museum, collection database

- "A scene to remember: how the directors of Titanic accurately recreated a poignant moment". The Independent.

Sources

- Swinburne, Henry Lawrence; Wilkinson, Norman; Jellicoe, John. (1907). The Royal Navy. London: A. and C. Black. OCLC 3594590

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Norman Wilkinson. |

- Behrens, Roy R. (2002), False Colors: Art, Design and Modern Camouflage. Dysart, Iowa: Bobolink Books. ISBN 0-9713244-0-9.

- Behrens, Roy R. (2009), Camoupedia: A Compendium of Research on Art, Architecture and Camouflage. Dysart, Iowa: Bobolink Books. ISBN 978-0-9713244-6-6.

- Cole, Beverley and Richard Durack (1992), Railway Posters, 1923–1947. London: Laurence King.

- Goodden, Henrietta (2007), Camouflage and Art: A Design for Deception in World War 2. London: Unicorn Press. ISBN 978-0-906290-87-3.

- Hartcup, Guy (1980), Camouflage: A History of Concealment and Deception in War. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Newark, Tim (2007), Camouflage. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-51347-7.

- Wilkinson, Norman (1919), "The Dazzle Painting of Ships," as reprinted (in abridged form) in James Bustard, Camouflage. Exhibition catalogue. Edinburgh: Scottish Arts Council, 1988, unpaged.

- ___ (1969), A Brush with Life. London: Seeley Service.

External links

- 160 paintings by or after Norman Wilkinson at the Art UK site