Grand National Assembly of Turkey

The Grand National Assembly of Turkey (Turkish: Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi), usually referred to simply as the TBMM or Parliament (Turkish: Meclis or Parlamento), is the unicameral Turkish legislature. It is the sole body given the legislative prerogatives by the Turkish Constitution. It was founded in Ankara on 23 April 1920 in the midst of the National Campaign. The parliament was fundamental in the efforts of Mareşal Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, 1st President of the Republic of Turkey, and his colleagues to found a new state out of the remnants of the Ottoman Empire.

Grand National Assembly of Turkey Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi | |

|---|---|

| 27th Parliament of Turkey | |

.svg.png) Seal of the Turkish Parliament | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | April 23, 1920 July 20, 1961 (Bicameral) November 9, 1982 |

| Disbanded | May 27, 1960 September 12, 1980 |

| Preceded by | General Assembly of the Ottoman Empire |

| Leadership | |

Süreyya Sadi Bilgiç (AKP) since 24 February 2019 Haydar Akar (CHP) Nimetullah Erdoğmuş (HDP) Celal Adan (MHP) since 12 July 2018 | |

Leader of the House | |

| Structure | |

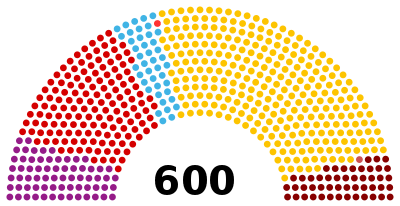

| Seats | 600 |

_.svg.png) | |

Political groups | Government (291)

Supported by (50) Opposition (245)

Vacant (14)

|

| Elections | |

| Party-list proportional representation D'Hondt method | |

Last election | 24 June 2018 |

Next election | 25 June 2023 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Grand National Assembly of Turkey Bakanlıklar Ankara, 06543 Turkey | |

| Website | |

| Grand National Assembly of Turkey | |

History

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Turkey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Turkey has had a history of parliamentary government before the establishment of the current national parliament. These include attempts at curbing absolute monarchy during the Ottoman Empire through constitutional monarchy, as well as establishments of caretaker national assemblies immediately prior to the declaration of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 but after the de facto dissolution of the Ottoman Empire earlier in the decade.

Parliamentary practice before the Republican era

Ottoman Empire

There were two parliamentary governments during the Ottoman period in what is now Turkey. The First Constitutional Era lasted for only two years, elections being held only twice. After the first elections, there were a number of criticisms of the government due to the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–1878 by the representatives, and the assembly was dissolved and an election called on 28 June 1877. The second assembly was also dissolved by the sultan Abdul Hamid II on 14 February 1878, the result being the return of absolute monarchy with Abdul Hamid II in power and the suspension of the Ottoman constitution of 1876, which had come with the democratic reforms resulting in the first constitutional era.[1]

The Second Constitutional Era is considered to have begun on 23 July 1908. The constitution that was written for the first parliament included control of the sultan on the public and was removed during 1909, 1912, 1914 and 1916, in a session known as the "declaration of freedom". Most of the modern parliamentary rights that were not granted in the first constitution were granted, such as the abolition of the right of the Sultan to deport citizens that were claimed to have committed harmful activities, the establishment of a free press, a ban on censorship. Freedom to hold meetings and establish political parties was recognized, and the government was held responsible to the assembly, not to the sultan.[2]

During the two constitutional eras of the Ottoman Empire, the Ottoman parliament was called the General Assembly of the Ottoman Empire and was bicameral. The upper house was the Senate of the Ottoman Empire, the members of which were selected by the sultan.[3] The role of the Grand Vizier, the centuries-old top ministerial office in the empire, transformed in line with other European states into one identical to the office of a Prime Minister, as well as that of the speaker of the Senate. The lower chamber of the General Assembly was the Chamber of Deputies of the Ottoman Empire, the members of which were elected by the general public.[4]

Establishment of the national Parliament

After World War I, the victorious Allied Powers sought the dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire through the Treaty of Sèvres.[5] The political existence of the Turkish nation was to be completely eliminated under these plans, except for a small region. Nationalist Turkish sentiment rose in the Anatolian peninsula, engendering the establishment of the Turkish national movement. The political developments during this period have made a lasting impact which continues to affect the character of the Turkish nation. During the Turkish War of Independence, Mustafa Kemal put forth the notion that there would be only one way for the liberation of the Turkish people in the aftermath of World War I, namely, through the creation of an independent, sovereign Turkish state. The Sultanate was abolished by the newly founded parliament in 1922, paving the way for the formal proclamation of the republic that was to come on 29 October 1923.[6]

Transition to Ankara

Mustafa Kemal, in a speech he made on 19 March 1920 announced that "an Assembly will be gathered in Ankara that will possess extraordinary powers" and communicated how the members who would participate in the assembly would be elected and the need to realise elections, at the latest, within 15 days.[7] He also stated that the members of the dispersed Ottoman Chamber of Deputies could also participate in the assembly in Ankara, to increase the representative power of the parliament. These elections were held as planned, in the style of the elections of the preceding Chamber of Deputies, in order to select the first members of the new Turkish assembly. This Grand National Assembly, established on national sovereignty, held its inaugural session on 23 April 1920.[6] From this date until the end of the Turkish War of Independence in 1923, the provisional government of Turkey was known as the Government of the Grand National Assembly.

Republican era

1923–1945

.jpg)

The first trial of multi-party politics, during the republican era, was made in 1924 by the establishment of the Terakkiperver Cumhuriyet Fırkası at the request of Mustafa Kemal, which was closed after several months. Following a 6-year one-party rule, after the foundation of the Serbest Fırka (Liberal Party) by Ali Fethi Okyar, again at the request of Mustafa Kemal, in 1930, some violent disorders took place, especially in the eastern parts of the country. The Liberal Party was dissolved on 17 November 1930 and no further attempt at a multiparty democracy was made until 1945.[8]

1945–1960

The multi-party period in Turkey was resumed by the founding of the National Development Party (Milli Kalkınma Partisi), by Nuri Demirağ, in 1945. The Democrat Party was established the following year, and won the general elections of 1950; one of its leaders, Celal Bayar, becoming President of the Republic and another, Adnan Menderes, Prime Minister.[9]

1960–1980

After the military forces intervened in the country's political life on 27 May 1960, Prime Minister Adnan Menderes, President Celal Bayar, and all the ministers and members of the Assembly were arrested.[10] The Assembly was closed. The Committee of National Unity, CNU (Milli Birlik Komitesi), assumed all the powers of the Assembly by a provisional constitution and began to run the country. Executive power was used by ministers appointed by the CNU.[11]

The members of the CNU began to work on a new and comprehensive constitution. The Constituent Assembly (Kurucu Meclis), composed of members of the CNU and the members of the House of Representatives, was established to draft a new constitution on 6 January 1961. The House of Representatives consisted of those appointed by the CNU, representatives designated by two parties of that time (PRP and Republican Villagers National Party, RVNP), and representatives of various professional associations.[12]

The constitutional text drafted by the Constituent Assembly was presented to the voters in a referendum on 9 July 1961, and was accepted by 61.17% of the voters. The 1961 Constitution, the first prepared by a Constituent Assembly and the first to be presented to the people in a referendum, included innovations in many subjects.[12]

The 1961 Constitution stipulated a typical parliamentarian system. According to the Constitution, Parliament was bicameral. The legislative power was vested in the House of Representatives and the Senate. while the executive authority was vested in the President and the Council of Ministers. The Constitution envisaged a Constitutional Court.[12]

The 1961 Constitution regulated fundamental rights and freedom, including economic and social rights, over a wide spectrum and adopted the principles of a democratic social state and the rule of law. The 1961 Constitution underwent many comprehensive changes after the military memorandum of 12 March 1971, but continued to be in force until the military coup of 1980.[13]

1980–2018

The country underwent a military coup on 12 September 1980. The Constitution was suspended and political parties were dissolved.[14] Many politicians were forbidden from entering politics again. The military power ruling the country established a "Constituent Assembly", as had been done in 1961. The Constituent Assembly was composed of the National Security Council and the Advisory Assembly. Within two years, the new constitution was drafted and was presented to the referendum on 7 November 1982. Participation in the referendum was 91.27%. As a result, the 1982 Constitution was passed with 91.37% of the votes.[15]

The greatest change brought about by the 1982 Constitution was the unicameral parliamentary system.[14] The number of MPs were 550 members. The executive was empowered and new and more definite limitations were introduced on fundamental rights and freedoms. Also a 10% Electoral threshold was introduced.[16] Except for these aspects, the 1982 Constitution greatly resembled the 1961 Constitution.

The 1982 Constitution, from the time it was accepted until the present time, has undergone many changes, especially the "integration laws", which have been introduced within the framework of the European Union membership process, and which has led to a fundamental evolution.[13]

2018–present

After the 2017 constitutional referendums, the first general election of the Assembly would under a presidential system, with an executive president who will have the power to renew the elections for the Assembly.[17] The new Assembly would increase the number of MPs from 550 to 600.[18]

Composition

There are 600 members of parliament (deputies) who are elected for a five-year term by the D'Hondt method, a party-list proportional representation system, from 87 electoral districts which represent the 81 administrative provinces of Turkey (Istanbul and Ankara are divided into three electoral districts whereas İzmir and Bursa are divided into two each because of its large populations). To avoid a hung parliament and its excessive political fragmentation, since 1982 a party must win at least 10% of the national vote to qualify for representation in the parliament.[16] As a result of this threshold, only two parties won seats in the legislature after the 2002 elections and three in 2007. The 2002 elections saw every party represented in the previous parliament ejected from the chamber and parties representing 46.3% of the voter turnout were excluded from being represented in parliament.[16] This threshold has been criticized, but a complaint with the European Court for Human Rights was turned down.[19]

Independent candidates may also run[20] and can be elected without needing a threshold.[21]

Speaker of the parliament

A new term in the parliament began on 23 June 2015, after the June 2015 General Elections. Deniz Baykal from the CHP temporarily served as the speaker, as it is customary for the oldest member of the TBMM to serve as speaker during a hung parliament. İsmail Kahraman was elected after the snap elections on 22 November 2015.[22]

Members (since 1999)

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 1999–2002

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 2002–2007

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 2007–2011

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 2011–2015

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, June to Nov, 2015

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 2015-2018

- List of members of the parliament of Turkey, 2018-2023

Parliamentary groups

Parties who have at least 20 deputies may form a parliamentary group. Currently there are five parliamentary groups at the GNAT: AKP, which has the highest number of seats, CHP, MHP, İyi Party and HDP.[23]

Committees

Specialized committees

- Constitution committee (26 members)[24]

- Justice committee (24 members)[25]

- National Defense committee (24 members)[26]

- Internal affairs committee (24 members)[27]

- Foreign affairs committee (24 members)[28]

- National Education, Culture, Youth and Sports committee (24 members)[29]

- Development, reconstruction, transportation and tourism committee (24 members)[30]

- Environment committee (24 members)[31]

- Health, family, employment, social works committee (24 members)[32]

- Agriculture, forestry, rural works committee (24 members)[33]

- Industry, Commerce, Energy, Natural Resources, Information and Technology Committee (24 members)[34]

- Equal Opportunity for Women and Men Committee (26 members)[35]

- Application committee (13 members)[36]

- Planning and Budget committee (39 members)[37]

- Public economic enterprises committee (35 members)[38]

- Committee on inspection of Human rights (23 members)[39]

- Security and Intelligence Committee (17 members)[40]

- European Union Harmonization Committee (21 members) (not available in Parliamentary Procedures)[41]

Parliamentary research committees

These committees are one of auditing tools of the Parliament. The research can begin upon the demand of the Government, political party groups or min 20 MPs. The duty is assigned to a committee whose number of members, duration of work and location of work is determined by the proposal of the Parliamentary Speaker and the approval of the General Assembly.[42][43]

Parliamentary investigation committees

These committees are established if any investigation demand re the president, vice president, and ministers occur and approved by the General Assembly through hidden voting.[43]

International committees

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Organisation of Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (8 members)[44]

- Parliamentary Assembly of NATO (18 members)[45]

- The Council of Europe Parliamentary Assembly (18 members)[46]

- Turkey – European Union Joint Parliamentary Committee (25 members)[47]

- Parliamentary Union of the Organization of Islamic Conference (5 members)[48]

- Union of Asian Parliaments (5 members)[49]

- Parliamentary Assembly of Union for the Mediterranean (7 members)[50]

- Inter-parliamentary Union (9 members)[51]

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation (9 members)[52]

- Mediterranean Parliamentary Assembly (5 members)[53]

- Parliamentary Assembly of Turkic-Speaking Countries (9 members)[54]

- Parliamentary Assembly of Economic Cooperation Organization (5 members)[55]

- Parliamentary Assembly of the Southeast European Cooperation Process (6 members)[56]

An MP can attend more than one committee if s/he is not a member of Application Committee or Planning and Budgeting Committee. Members of those committees can not participate in any other committees. On the other hand, s/he does not have to work for a committee either. Number of members of each committee is determined by the proposal of the Advisory Council and the approval of the General Assembly.[43]

Sub committees are established according to the issue that the committee receives. Only Public Economic Enterprises (PEEs) Committee has constant sub committees that are specifically responsible for a group of PEEs.[43]

Committee meetings are open to the MPs, the Ministers’ Board members and the Government representatives. The MPs and the Ministers’ Board members can talk in the committees but can not make amendments proposals or vote. Every MP can read the reports of the committees.[43]

NGOs can attend the committee meetings upon the invitation of the committee therefore volunteer individual or public participation is not available. Media, but not the visual media, can attend the meetings. The media representatives are usually the parliamentary staff of the media institutions. The committees can prevent the attendance of the media with a joint decision.[57]

Current composition

The 27th Parliament of Turkey took office on 7 July 2018, following the ratification of the results of the general election held on 1 November 2015. The composition of the 27th Parliament, is shown below.

Changes since March 2020

_.svg.png)

Latest election results

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alliance | Party | Votes | Seats | ||||||

| # | % | ± | # | ± | % | ||||

| People's Alliance Cumhur İttifakı | Justice and Development Party* Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi | 21,335,579 | 42.56 | -6.94 | 295 | -22 | 49.17 | ||

| Nationalist Movement Party Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi | 5,564,517 | 11.10 | -0.80 | 49 | +9 | 8.17 | |||

| People's Alliance total | 26,900,096 | 53.66 | -7.74 | 344 | -13 | 57.33 | |||

| Nation Alliance Millet İttifakı | Republican People's Party* Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi | 11,348,899 | 22.64 | -2.68 | 146 | +12 | 24.33 | ||

| İyi Party* İyi Parti | 4,990,710 | 9.96 | New | 43 | New | 7.17 | |||

| Felicity Party* Saadet Partisi | 673,731 | 1.34 | +0.66 | 0 | ±0 | 0.00 | |||

| Nation Alliance total | 17,013,340 | 33.94 | +7.94 | 189 | +55 | 31.50 | |||

| Peoples' Democratic Party Halkların Demokratik Partisi | 5,866,309 | 11.70 | +0.94 | 67 | +8 | 11.17 | |||

| Free Cause Party Hür Dava Partisi | 157,612 | 0.31 | +0.31 | 0 | ±0 | 0.00 | |||

| Patriotic Party Vatan Partisi | 117,779 | 0.23 | -0.02 | 0 | ±0 | 0.00 | |||

| Other Diğer | 75,283 | 0.15 | -1.44 | 0 | ±0 | 0.00 | |||

| Invalid/blank votes | 1,053,310 | – | – | – | – | – | |||

| Total | 51,183,729 | 100.00 | – | 600 | +50 | 100.00 | |||

| Registered voters/turnout | 59,354,840 | 86.23 | +1.05 | – | – | – | |||

| Source: Anadolu Ajansı | |||||||||

| *Notes: Two members of the Felicity Party were elected on the Republican People's Party list, one member of the Democrat Party was elected on the İyi Party list, and one member of the Great Union Party was elected on the Justice and Development Party list. | |||||||||

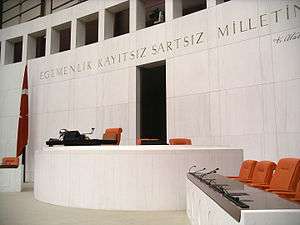

Parliament Building

The current Parliament Building is the third to house the nation's parliament. The building which first housed the Parliament was converted from the Ankara headquarters of the Committee of Union and Progress, the political party that overthrew Sultan Abdulhamid II in 1909 in an effort to bring democracy to the Ottoman Empire. Designed by architect Hasip Bey,[60] it was used until 1924 and is now used as the locale of the Museum of the War of Independence, the second building which housed the Parliament was designed by architect Vedat (Tek) Bey (1873–1942) and used from 1924 to 1960.[60] It is now been converted as the Museum of the Republic. The Grand National Assembly is now housed in a modern and imposing building in the Bakanlıklar neighborhood of Ankara.[61] The monumental building's project was designed by architect and professor Clemens Holzmeister (1886–1993).[60] The building was depicted on the reverse of the Turkish 50,000 lira banknotes of 1989–1999.[62] The building was hit by airstrikes three times during the 2016 Turkish coup d'état attempt, suffering noticeable damage.[63] Later, the Parliament went through a revision in the summer of 2016.[64]

Picture gallery

The current TBMM front facade.

The current TBMM front facade.- The old TBMM.

Balcony of the old TBMM.

Balcony of the old TBMM. The General Assembly is the meeting place of the TBMM.

The General Assembly is the meeting place of the TBMM. President Atatürk entering the TBMM.

President Atatürk entering the TBMM. Funeral of President Demirel.

Funeral of President Demirel..jpg) Garden of the second TBMM.

Garden of the second TBMM.- A scale model of the current TBMM.

Discussion in the TBMM in the 1980s.

Discussion in the TBMM in the 1980s. Hatı Çırpan at the rostrum.

Hatı Çırpan at the rostrum. The predecessor of the TBMM was the Ottoman Parliament.

The predecessor of the TBMM was the Ottoman Parliament._p733_-_THE_OTTOMAN_PARLIAMENT%2C_1877.jpg) The Ottoman Parliament in 1877.

The Ottoman Parliament in 1877.

See also

- List of Chairmen of the Senate of Turkey

- List of Speakers of the Parliament of Turkey

- Politics of the Republic of Turkey

- List of legislatures by country

Notes

- Elected on Justice and Development Party list, but do not sit together in parliament

- Elected on the Peoples' Democratic Party list, but do not sit together in parliament

- Elected on the İYİ Party list, but do not sit together in parliament

- Elected on the Republican People's Party list, but do not sit together in parliament

References

Citations

- "Türk Demokrasi Tarihinde I. Meşrutiyet Dönemi" (PDF) (in Turkish). Gazi University. 2005. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Yüzüncü Yılında II. Meşrutiyet'in İlanı Üzerine Bir İnceleme" (in Turkish). Gazi University. 2008. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Mütareke Dönemi'nde Ayan Meclisi'nin Çalışmaları" (PDF). The Journal of International Social Research (in Turkish). 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "İlk Osmanlı Seçimleri ve Parlamentosu". Sosyoloji Dergisi (in Turkish). 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. Morrow. ISBN 0-688-03093-9.

- "The Fundamental Law and abolition of the sultanate". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Olağanüstü yetkiler taşıyan bir meclisin Ankara'da toplanması kararı". atam.gov.tr (in Turkish). Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Opposition". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Turkey under the Democrats, 1950–60". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "The military coup of 1960". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "The National Unity Committee". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Turkey under the Democrats, 1950–60". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Developer, Design: Emre Baydur, IT. "The Grand National Assembly of Turkey". global.tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- "The 1980s". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "1982 referandumu: Mavi, Beyaz'a karşı" (in Turkish). BBC. 4 April 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Crossing the threshold – the Turkish election". www.electoral-reform.org.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- "AKP under pressure: failed coup attempt, crackdown on dissidents, and economic crisis". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- "Anayasa değişikliği kabul edildi! Yeni anayasa ne getiriyor?". Milliyet (in Turkish). 17 April 2017. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- hlsjrnldev. "ECHR Upholds Turkey's 10% Threshold in Elections". Retrieved 17 February 2020.

- Turkish Directorate General of Press and Information (24 August 2004). "Political Structure of Turkey". Turkish Prime Minister's Office. Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 14 December 2006.

- e.g. Istanbul in 2011 has a successful candidate at 3.2% Archived 15 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Meclis Başkanı'nı seçti". Milliyet. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 25 November 2015.

- "IPU PARLINE database: TURKEY (Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (T.B.M.M)), Full text". archive.ipu.org. Retrieved 18 February 2020.

- "Anayasa Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Adalet Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Milli Savunma Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "İçişleri Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Dışişleri Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Milli Eğitim, Kültür, Gençlik ve Spor Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Bayındırlık, İmar, Ulaştırma ve Turizm Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Çevre Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Sağlık, Aile, Çalışma ve Sosyal İşler Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Tarım, Orman ve Köyişleri Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Sanayi, Ticaret, Enerji, Tabii Kaynaklar, Bilgi ve Teknoloji Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Kadın Erkek Fırsat Eşitliği Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Dilekçe Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Plan ve Bütçe Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Kamu İktisadi Teşebbüsleri Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "İnsan Haklarını İnceleme Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Güvenlik ve İstihbarat Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Avrupa Birliği Uyum Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Köroğlu, Veli (December 2006). "Meclis Araştırması". Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi. Vol. 3 no. 2. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi İçtüzüğü" (PDF). tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Avrupa Güvenlik ve İşbirliği Teşkilatı Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Nato Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Avrupa Konseyi Parlamenter Meclisi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Türkiye - Avrupa Birliği Karma Parlamento Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "İslam İş Birliği Teşkilatı Parlamento Birliği". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Asya Parlamentoları Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Akdeniz İçin Birlik Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Parlamentolararası Birlik Komisyonu". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Karadeniz Ekonomik İşbirliği Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Akdeniz Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Türk Dili Konuşan Ülkeler Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Ekonomik İş Birliği Teşkilatı Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Güney Doğu Avrupa İş Birliği Süreci Parlamenter Asamblesi". tbmm.gov.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Türkiye Parlamentosunda Açıklık ve Şeffaflık, Yasama Süreçlerine Sivil Katılım" (PDF). tusev.org.tr. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- SABAH, DAILY (12 March 2020). "Political parties alarmed over coronavirus spread to Turkey, measures in place". Daily Sabah. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Turkey's opposition CHP and HDP to seek allies at party congresses". Ahval. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "The Grand National Assembly of Turkey".

- Yale, Pat; Virginia Maxwell; Miriam Raphael; Jean-Bernard Carillet (2005). Turkey. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-683-8.

- Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey Archived 3 June 2009 at WebCite. Banknote Museum: 7. Emission Group – Fifty Thousand Turkish Lira – I. Series Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine & II. Series Archived 22 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved on 20 April 2009.

- "Ankara parliament building 'bombed from air' – state agency". RT. 15 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2019.

- "Meclis yaz dönemini tadilatla geçirecek" (in Turkish). TRT News. 23 August 2016.

Sources

- Kinross, Patrick (1977). The Ottoman Centuries: The Rise and Fall of the Turkish Empire. Morrow. ISBN 0-688-03093-9.

- Shaw, Stanford Jay; Shaw, Ezel Kural (1977). History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29163-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grand National Assembly of Turkey. |