Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15

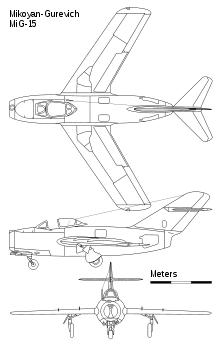

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (Russian: Микоян и Гуревич МиГ-15; USAF/DoD designation: Type 14; NATO reporting name: Fagot) is a jet fighter aircraft developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich for the Soviet Union. The MiG-15 was one of the first successful jet fighters to incorporate swept wings to achieve high transonic speeds. In combat over Korea, it outclassed straight-winged jet day fighters, which were largely relegated to ground-attack roles, and was quickly countered by the similar American swept-wing North American F-86 Sabre.

| MiG-15 | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| A Soviet Air Forces MiG-15UTI two-seater trainer over Duxford Air Festival 2017 | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Mikoyan-Gurevich |

| First flight | 30 December 1947 |

| Introduction | 1949 |

| Status | In limited service with the Korean People's Army Air Force |

| Primary users | Soviet Air Forces (historical)

|

| Number built | 13,130 in the USSR + at least 4,180 under license |

| Developed into | Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 |

When refined into the more advanced MiG-17, the basic design would again surprise the West when it proved effective against supersonic fighters such as the Republic F-105 Thunderchief and McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II in the Vietnam War of the 1960s.

The MiG-15 is believed to have been one of the most produced jet aircraft; in excess of 13,000 were manufactured.[1] Licensed foreign production may have raised the production total to almost 18,000. The MiG-15 remains in service with the Korean People's Army Air Force as an advanced trainer.

Design and development

The first turbojet fighter developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich OKB was the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-9, which appeared in the years immediately after World War II. It used a pair of reverse-engineered German BMW 003 engines.[2] The MiG-9 was a troublesome design that suffered from weak, unreliable engines and control problems. Categorized as a first-generation jet fighter, it was designed with the straight-style wings common to piston-engined fighters.

The Germans had been unable to develop turbojets with thrust over 1,130 kilograms-force (11,100 N; 2,500 lbf) running at the time of the surrender in May 1945, which limited the performance of immediate Soviet postwar jet aircraft designs. They did inherit the technology of the advanced axial-compressor Junkers 012 and BMW 018 engines, in the class of the later Rolls-Royce Avon, that were some years ahead of the then currently available British Rolls-Royce Nene engine. The Soviet aviation minister Mikhail Khrunichev and aircraft designer A. S. Yakovlev suggested to Premier Joseph Stalin that the USSR buy the conservative but fully developed Nene engines from Rolls-Royce (having been alerted to the fact that the U.K. Labour government wanted to improve post-war UK-Russia foreign relations) for the purpose of copying them in a minimum of time. Stalin is said to have replied, "What fool will sell us his secrets?"[3]

However, he gave his consent to the proposal and Mikoyan, engine designer Vladimir Klimov, and others travelled to the United Kingdom to request the engines. To Stalin's amazement, the British Labour government and its Minister of Trade, Sir Stafford Cripps, were perfectly willing to provide technical information and a license to manufacture the Rolls-Royce Nene. Sample engines were purchased and delivered with blueprints. Following evaluation and adaptation to Russian conditions, the windfall technology was tooled for mass-production as the Klimov RD-45 to be incorporated into the MiG-15.[3]

To take advantage of the new engine, the Council of Ministers ordered the Mikoyan-Gurevich OKB to build two prototypes for an advanced high-altitude daytime interceptor to defend against bombers. It was to have a top speed of 1,000 kilometres per hour (620 mph) and a range of 1,200 kilometres (750 mi).[4]

Designers at MiG's OKB-155 started with the earlier MiG-9 jet fighter. The new fighter used Klimov's British-derived engines, swept wings, and a tailpipe going all the way back to a swept tail. The German Me 262 was the first fighter fitted with an 18.5° wing sweep, but it was introduced merely to adjust the center of gravity of its heavy Junkers Jumo 004 pioneering axial-compressor turbojet engines. Further experience and research during World War II later established that swept wings would give better performance at transonic speeds. At the end of World War II, the Soviets seized many of the assets of Germany's aircraft industry. The MiG team studied these plans, prototypes and documents, particularly swept-wing research and designs, even going so far as to produce a flying testbed in 1945 to investigate swept-wing design concepts as the piston-engined "pusher"-layout, MiG-8 Utka (Russian for "duck", from its tail-first canard design). The swept wing later proved to have a decisive performance advantage over straight-winged jet fighters when it was introduced into combat over Korea.

The design that emerged had a mid-mounted 35-degree swept wing with a slight anhedral and a tailplane mounted up on the swept tail. Western analysts noted that it strongly resembled Kurt Tank's Focke-Wulf Ta 183, a later design than the Me 262 that never progressed beyond the design stage . While the majority of Focke-Wulf engineers (in particular, Hans Multhopp, who led the Ta 183 development team) were captured by Western armies, the Soviets did capture plans and wind-tunnel models for the Ta 183.[5] The MiG-15 bore a much stronger likeness to the Ta 183 than the American F-86 Sabre, which also incorporated German research. The MiG-15 does bear a resemblance in layout, sharing the high tailplane and nose-mounted intake, although the aircraft are different in structure, details, and proportions. The MiG-15's design understandably shared features, and some appearance commonalities with the MiG design bureau's own 1945–46 attempt at a Soviet-built version of the Messerschmitt Me 263 rocket fighter in the appearance of its fuselage. The new MiG retained the previous straight-winged MiG-9's wing and tailplane placement while the F-86 employed a more conventional low-winged design. To prevent confusion during the height of combat the US painted their aircraft with bright stripes to distinguish them.[6]

The resulting prototypes were designated I-310.[7] The I-310 was a swept-wing fighter with 35-degree sweep in wings and tail, with two wing fences fitted to each wing to improve airflow over the wing. The design used a single Rolls-Royce Nene fed by a split-forward air intake. A duct carried intake air around the cockpit area and back together ahead of the engine.[7][8] Its first flight was 30 December 1947,[9] some two months after the American F-86 Sabre had first flown. It demonstrated exceptional performance, reaching 1,042 kilometres per hour (647 mph) at 3,000 metres (9,800 ft).[10]

The Soviet Union's first swept-wing jet fighter had been the underpowered Lavochkin La-160, which was otherwise more similar to the MiG-9. The Lavochkin La-168, which reached production as the Lavochkin La-15, used the same engine as the MiG but used a shoulder mounted wing and t-tail; it was the main competitive design. Eventually, the MiG design was favoured for mass production. Designated MiG-15, the first production example flew on 31 December 1948. It entered Soviet Air Force service in 1949, and subsequently received the NATO reporting name "Fagot". Early production examples had a tendency to roll to the left or to the right due to manufacturing variances, so aerodynamic trimmers called "nozhi" (knives) were fitted to correct the problem, the knives being adjusted by ground crews until the aircraft flew correctly.[3]

An improved variant, the MiG-15bis ("second"), entered service in early 1950 with a Klimov VK-1 engine, another version of the Nene with improved metallurgy over the RD-45, plus minor improvements and upgrades.[11] Visible differences were a headlight in the air intake separator and horizontal upper edge airbrakes. The 23 mm cannon were placed more closely together in their undercarriage. Some "bis" aircraft also adopted under-wing hardpoints for unguided rocket launchers or 50–250 kg (110–550 lb) bombs. Fighter-bomber modifications were dubbed "IB", "SD-21", and "SD-5". About 150 aircraft were upgraded to SD-21 specification during 1953–1954.

The MiG-15 arguably had sufficient power to dive at supersonic speeds, but the lack of an "all-flying" tail greatly diminished the pilot's ability to control the aircraft as it approached Mach 1. As a result, pilots understood they must not exceed Mach 0.92, where the flight surfaces became ineffective. Additionally, the MiG-15 tended to spin after it stalled, and often the pilot could not recover.[12] Later MiGs incorporated all-flying tails.

The MiG-15 was originally intended to intercept American bombers like the B-29. It was even evaluated in mock air-to-air combat trials with a captured U.S. B-29, as well as the later Soviet B-29 copy, the Tupolev Tu-4. To ensure the destruction of such large bombers, the MiG-15 carried autocannons: two 23 mm with 80 rounds per gun and a single 37 mm with 40 rounds. These weapons provided tremendous punch in the interceptor role, but their limited rate of fire and relatively low velocity made it more difficult to score hits against small and manoeuvrable enemy jet fighters in air-to-air combat. The 23 mm and 37 mm also had radically different ballistics, and some United Nations pilots in Korea had the unnerving experience of 23 mm shells passing over them while the 37 mm shells flew under. The cannon were fitted into a simple pack that could be winched out of the bottom of the nose for servicing and reloading, allowing pre-prepared packs to be rapidly swapped out. (Some sources mistakenly claim the pack was added in later models.)[3]

Operational history

The MiG-15 was widely exported, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) receiving MiG-15bis models in 1950. Its baptism of fire occurred during the last phases (1946–49) of the Chinese Civil War. During the first months of 1950, the aviation of Nationalist China attacked from Taiwan the communist position in continental China, especially Shanghai. Mao Zedong requested the military assistance of the USSR, and the 50th IAD (Истребительная Авиадивизия, ИАД; Istrebitelnaya Aviadiviziya; Fighter Aviation Division) equipped with the MiG-15bis was deployed in the southern part of the PRC. On 28 April 1950, Captain Kalinikov shot down a P-38 of the Kuomintang, scoring the first aerial victory of the MiG-15. Another followed on 11 May, when Captain Ilya Ivanovich Schinkarenko downed the B-24 Liberator of Li Chao Hua, commander of the 8th Air Group of the nationalist Air Force.

Chinese MiG-15s took part in the first jet-versus-jet dogfights during the Korean War. The swept-wing MiG-15 quickly proved superior to the first-generation, straight-wing jets of western air forces such as the Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star and the British Gloster Meteor, as well as piston-engined P-51 Mustangs and Vought F4U Corsairs with the MiG-15 of First Lieutenant Semyon Fyodorovich Khominich scoring the first jet-vs-jet victory in history when he bagged the F-80C of Frank Van Sickle, who died in the encounter (the USAF credits the loss to North Korean flak).[13] Only the F-86 Sabre was a match for the MiG.

The Korean War (1950–1953)

When the Korean War broke out on 25 June 1950, the Korean People's Air Force (KPAF) was equipped with World War II-vintage Soviet prop-driven fighters, including 93 Il-10s and 79 Yak-9Ps,[14] and "40–50 assorted transport/liaison/trainer aircraft".[15] The vast numerical and technical superiority of the United States Air Force (USAF), led by advanced jets such as Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star and Republic F-84 Thunderjet fighters, quickly achieved air superiority, thus laying North Korea's cities bare to the destructive power of USAF B-29 bombers, which, together with Navy and Marine aircraft, roamed the skies largely unopposed for a time.

In February 1950, the 50th IAD had already been moved to China to support the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) defending Shanghai and begin training Chinese pilots in the MiG-15. The Soviet pilots and technicians who were already in China relocated from Shanghai to North East China at the end of 1950. In the Soviet Union, more MiG-15 pilots were recruited; the volunteers had to be younger than 27 years and priority was given to World War II veterans. They formed the 29th GvIAP, which formed the core of the Soviet unit, the 64th Fighter Aviation Corps (64th IAK).

The MiG-15's performance amazed its Western opponents. The British Chief of the Air Staff said "Not only is it faster than anything we are building today, but it is already being produced in very large numbers [...] The Russians, therefore, have achieved a four year lead over British development in respect of the vitally important interceptor fighter".[16] The MiG-15 proved very effective in its designed role against formations of B-29 heavy bombers, shooting down numerous bombers. In a match-up with the F-86, the results were not as clear-cut, and Americans claimed that the F-86 had the advantage in combat kills. The Soviet 64th IAK claimed 1,106 UN aircraft destroyed in the Korean War, compared to Allied records that 142 Allied aircraft were downed by Soviet MiG-15 pilots. Western experts do acknowledge many Soviet pilots earned bigger individual scores than their American counterparts due to a number of factors, though overall figures of NATO were probably overstated.[17]

For many years, the participation of Soviet aircrews in the Korean War was widely suspected by the UN forces, but consistently denied by the Soviet Union. With the end of the Cold War Soviet pilots who participated in the conflict have begun to reveal their role.[18] Soviet aircraft were adorned with North Korean or Chinese markings and pilots wore either North Korean uniforms or civilian clothes to disguise their origins. For radio communication, they were given cards with common Korean words for various flying terms spelled out phonetically in Cyrillic characters.[18] These subterfuges did not long survive the stresses of air-to-air combat, however, as pilots routinely communicated (cursed) in Russian. Soviet pilots were prevented from flying over areas in which they might be captured, which would indicate that the Soviet Union was an active combatant in the war.

.svg.png)

The USSR never acknowledged that its pilots ever flew over Korea during the Cold War. Americans who intercepted radio traffic during combat confirmed hearing Russian-speaking voices, but only the Communist Chinese and North Korean combatants took responsibility for the flying. Until the publishing of recent books by Chinese, Russian and ex-Soviet authors, such as Zhang Xiaoming, Leonid Krylov, Yuriy Tepsurkaev and Igor Seydov, little was known of the actual pilots. The Americans recognized the techniques of their opponents whom they called "honchos",[17] and dubbed "MiG Alley" the site of numerous dogfights in the northwestern portion of North Korea where the Yalu River empties into the Yellow Sea.

The Soviet fighters operated close to their bases, limited by the range of their aircraft, and were guided to the air battlefield by good ground control, which directed them to the most advantageous positions. They were not allowed to cross an imaginary line drawn from Wonsan to Pyongyang, and never to fly over sea. The MiG-15s always operated in pairs, with an attacking leader covered by a wingman. Most of the first regimental, squadron commanders and pilots in 1951 were World War II combat veterans, and were well prepared and trained. But from February 1952, when the crack pilots of the 303rd and 324th IAD were largely replaced by less experienced pilots, F-86 Sabres and their well-trained US pilots would keep the edge until the end of the war. Another advantage the Sabre pilots had was Chodo Island radar station, which provided radar coverage of MiG Alley.

Large formations of MiGs would lie in wait on the Chinese side of the border. When UN aircraft entered MiG Alley, the MiGs would swoop down from high altitude to attack. If they ran into trouble, they would try to escape back over the border into China. Soviet MiG-15 squadrons operated in big groups, but the basic formation was a six-aircraft group, divided into three pairs, each composed of a leader and a wingman:

- The first pair of MiG-15s attacked the enemy Sabres.

- The second pair protected the first pair.

- The third pair remained above, supporting the two other pairs when needed. This pair had more freedom and could also attack targets of opportunity, such as lone Sabres that had lost their wingmen.

MiG-15 entry in Far East Asia

In April 1950, Soviet MiG-15s flown by Soviet pilots first appeared over Shanghai, thwarting a Nationalist Chinese bombing campaign. The Soviets had secretly deployed MiG-15s to Antung next to the border with North Korea in August 1950 and were training Chinese MiG-15 pilots when China entered the war in support of North Korea. By October, the Soviet Union had agreed to provide air regiments of state-of-the-art Soviet-designed and -built MiG-15 fighters, along with the trained crews to fly them. Simultaneously, the Kremlin agreed to supply the Chinese and North Koreans with their own MiG-15s, as well as train their pilots. In November, the 50th IAD was ordered to join the fight with its MiG-15s, with their noses painted red and in North Korean markings, and more MiG-15 units were moved to the Far East. On 1 November 1950, eight MiG-15s intercepted about 15 USAF F-51D Mustangs, and First Lieutenant Fyodor V. Chizh shot down Aaron Abercombrie, killing the American pilot. Three MiG-15s of the same unit intercepted 10 F-80 Shooting Stars, and First Lieutenant Semyon Fyodorovich Khominich scored the first jet-vs-jet victory in history when he downed the F-80C of Frank Van Sickle, who also perished (USAF credits both losses to the action of the North Korean flak).[13] However, on 9 November, the Soviet MiG-15 pilots suffered their first loss when Lieutenant Commander William T. Amen off the aircraft carrier USS Philippine Sea shot down and killed Captain Mikhail F. Grachev while flying a Grumman F9F Panther.[19]

To counter this unexpected development, three squadrons of the F-86 Sabre, America's only operational jet with swept wings, were quickly rushed to the Far East in December.[20] On 17 December 1950, Lieutenant Colonel Bruce H. Hinton forced Major Yakov Nikanorovich Yefromeyenko to eject from his burning MiG.[13] In the following days, both sides fired at the other, with Captain Nikolay Yefremovich Vorobyov[21] shooting down the F-86A of Captain Lawrence V. Bach in his MiG-15bis on 22 December 1950.[13] Both sides exaggerated their claims of aerial victories that month. Sabre fliers claimed eight MiGs, and the Soviets 12 F-86s; the actual losses were three MiGs and at least four Sabres.

In October 1950, Stalin had promised to send ground weaponry to China and to transfer 16 aviation regiments to the northeastern area to protect Chinese territory. The MiG-15 squadrons earmarked for Korea were drawn from elite units, as opposed to the inexperienced MiG-15 pilots the US had fought in the winter of 1950. The first large Soviet aviation unit sent to Korea, the 324th IAD, was an air defense interceptor division commanded by Colonel Ivan Kozhedub, who, with 62 victories, was the top Allied (and Soviet) ace of World War II. In November 1950, the 151st and 28th IADs plus the veteran 50th IAD were reorganized into the 64th IAK (Air Fighter Corps).

At the end of 1950, the Soviet Union assigned a new unit to support China, the 324th IAD (made up of two regiments: 176th GIAP and 196th IAP). At that time, a MiG-15 interceptor regiment numbered 35 to 40 aircraft, and a division usually included three regiments. When the new unit arrived to air bases along the Yalu River in March 1951, it had undergone preliminary training at Soviet bases in the neighboring Maritime Military Districts and started an intense period of air-to-air training in the MiG-15. The Soviets trained alongside Chinese and Korean pilots. Both regiments of the 324th IAD redeployed to the forward airbase in Antung, and entered into battle in early April 1951. The 303rd IAD of General Georgiy A. Lobov arrived in Korea in June of that same year and commenced combat operations in August.

MiG pilots were instructed to jump the American formations in coordinated attacks from different directions, using both height and high speed in their favor. These tactics were tested on 12 April 1951 when 44 MiG-15s faced a USAF formation of 48 B-29 Superfortresses escorted by 96 jet fighters. The Soviet air units claimed to have shot down 29 American aircraft through the rest of the month: 11 F-80s, seven B-29s and nine F-51s.[13] 23 out of these 29 claims match acknowledged losses, but US sources assert that most of them were either operational or due to flak, admitting only four B-29s (a downed B-29, plus two B-29s and a RB-29 that crash-landed or were damaged beyond repair). US historians agree that the MiG-15 gained aerial superiority over northwestern Korea.[13]

Those first encounters established the main features of the aerial battles of the next two and a half years. The MiG-15 and MiG-15bis had a higher ceiling than all versions of the Sabre – 15,500 m (50,900 ft) versus 14,936 m (49,003 ft) of the F-86F – and accelerated faster than F-86A/E/Fs due to their better thrust-to-weight ratio – 1,005 km/h (624 mph) versus 972 km/h (604 mph) of the F-86F. The MiG-15's 2,800 m (9,200 ft) per minute climbing rate was also greater than the 2,200 m (7,200 ft) per minute of the F-86A and -E (the F-86F matched the MiG-15). A better turn radius above 10,000 m (33,000 ft) further distinguished the MiG-15, as did more powerful weaponry – one 37 mm N-37 cannon and two 23 mm NR-23 cannon, versus the inferior hitting power of the six 12.7 mm (.50 in) machine guns of the Sabre. But the MiG was slower at low altitude – 935 km/h (581 mph) in the MiG-15bis configuration as opposed to the 1,107 km/h (688 mph) of the F-86F. The Soviet World War II-era ASP-1N gyroscopic gunsight was less sophisticated than the accurate A-1CM and A4 radar ranging sights of the F-86E and -F. All Sabres could turn tighter below 8,000 m (26,000 ft).[23]

Thus, if the MiG-15 forced the Sabre to fight in the vertical plane or in the horizontal one above 10,000 m (33,000 ft), it gained a significant advantage. Furthermore, a MiG-15 could easily escape from a Sabre by climbing to its ceiling, knowing that the F-86 could not follow. Below 8,000 m (26,247 ft), however, the Sabre had a slight advantage over the MiG in most aspects excluding climb rate, especially if the Soviet pilot made the mistake of fighting in the horizontal plane.

The main mission of the MiG-15 was not to dogfight the F-86, but to counter the USAF Boeing B-29 Superfortress bombers. This mission was assigned to the elite of the Soviet Air Force (VVS), in April 1951 to the 324th IAD of Colonel Ivan Kozhedub, and later to the 303rd IAD of General Georgiy A. Lobov, who arrived to Korea in June of the same year.[13]

A total of 44 MiG-15s achieved victories in that mission on 12 April 1951 when they intercepted a large formation of 48 B-29 Superfortresses, 18 F-86 Sabres, 54 F-84 Thunderjets and 24 F-80 Shooting Stars heading towards the bridge linking North Korea and Red China over the Yalu river in Uiju. When the ensuing battle was finished, the experienced Soviet fliers had shot down or damaged beyond repair 10 B-29As, one F-86A and three F-80Cs for the loss of only one MiG.[13]

U.S. strategic bombers returned the week of 22–27 October to neutralize the North Korean aerodromes of Namsi, Taechon and Saamchan, taking further losses to the MiG-15. On 23 October 1951, 56 MiG-15bis intercepted nine B-29s escorted by 34 F-86s and 55 F-84Es. In spite of their numerical inferiority, the Soviet airmen shot down or damaged beyond repair eight B-29As and two F-84Es, losing only one MiG in return and leading Americans to call that day "Black Tuesday".[24] The most successful Soviet pilots that day were Lieutenant Colonel Aleksandr P. Smorchkov and 1st Lieutenant Dmitriy A. Samoylov. The former shot down a Superfortress on each of 22, 23 and 24 October.[13] Samoylov added two F-86As to his tally on 24 October 1951,[25][26] and on 27 October shot down two more aircraft: a B-29A and an F-84E.[25][27] These losses among the heavy bombers forced the Far East Air Forces High Command to cancel the precision daylight attacks of the B-29s and only undertake radar-directed night raids.[28]

From November 1951 to January 1952, both sides tried to achieve air superiority over the Yalu, or at least tried to deny it to the enemy, and in consequence, the intensity of the aerial combat reached peaks not seen before between MiG-15 and F-86 pilots. During the period from November 1950 to January 1952, no fewer than 40 Soviet MiG-15 pilots were credited as aces, with five or more victories. Soviet combat records show that the first pilot to claim his fifth aerial victory was Captain Stepan Ivanovich Naumenko on 24 December 1950.[19][29] The honor falls to Captain Sergei Kramarenko, when on 29 July 1951, he scored his actual fifth victory.[30] Approximately 16 out of those 40 pilots actually became aces, the most successful being Major Nikolay Sutyagin, credited with 22 victories, 13 of which were confirmed by the US; Colonel Yevgeny Pepelyaev with 19 claims, 15 confirmed; and Major Lev Shchukin with 17 credited, 11 verified.[31]

The MiG leaders, enjoying the advantage from the ground and the tactical advantage of an aircraft with superior altitude performance were able to dictate the tactical situation at least until the battle was started. They could decide to fight or stay out as they wished. The advantage of radar control from the ground also allowed the MiGs, if desired, to pass through the gaps in the F-86 patrol pattern.

First rotation: January 1952 to July 1952

At the end of January 1952, the 303rd IAD was replaced by the 97th (16th and 148th IAP) and in February the 324th IAD was replaced by the 190th IAD (256th, 494th and 821st IAP). These new units were poorly trained, the bulk of the pilots having only 50–60 hours flying the MiG. Consequently, those units suffered great losses by the now better prepared American Sabre pilots. At least two Soviet fliers became aces during that period: Majors Arkadiy S. Boytsov and Vladimir N. Zabelin, with six and nine victories respectively.[32]

During the six months of February to July 1952, they lost 81 MiGs, and 34 pilots were killed by F-86s, and in return they only shot down 68 UN aircraft (including 36 F-86s). The greatest losses came on 4 July 1952, when 11 MiGs were downed by Sabres, with one pilot killed in action. Contributing to all this was the secret "Maple Special" Operation, a plan by Colonel Francis Gabreski to cross the Yalu River into Manchuria (something officially forbidden) and catch the MiGs unaware during their takeoffs or landings, when they were at disadvantage: flying slow, at a low level, and sometimes short of ammunition and fuel.

Even under these circumstances, MiG-15 pilots would score at least two important victories against American aces:

- 10 February 1952: Major George Andrew Davis, Jr., an ace credited with 14 victories, 10 confirmed by Communist sources, was shot down and killed. The victor's identity was disputed between 1st Lieutenant Mikhail Akimovich Averin and Zhang Jihui.[32][33][34][35]

- 4 July 1952: A few seconds after shooting down 1st Lieutenant M. I. Kosynkin, future ace Captain Clifford D. Jolley was forced to eject out of his crippled F-86E after being caught by surprise by MiG-15bis pilot 1st Lieutenant Vasily Romanovich Krutkikh.[26][32][36][37]

Third rotation: July 1952 – July 1953

In May 1952, new and better trained PVO divisions, the 133rd and 216th IADs, arrived in Korea. They would replace the 97th and 190th by July 1952, and if they could not take aerial superiority away from the now well prepared Americans, then they certainly neutralized it between September 1952 and July 1953. In September 1952, the 32nd IAD also started combat operations. Again, the figures of victories and losses in the air are still debated by historians of the US and the former Soviet Union, but on at least three occasions, Soviet MiG-15 aces gained the upper hand against Sabre aces:

- 7 April 1953: The 10-kill ace Captain Harold E. Fischer was shot down over Manchuria shortly after causing damage to a Chinese and a Soviet MiG over Dapu airbase in Manchuria. The attacker's identity was disputed between 1st Lieutenant Grigoriy Nesterovich Berelidze and Han Dechai.[38][39]

- 12 April 1953: Captain Semyon Alekseyevich Fedorets, a Soviet ace with eight victories, shot down the F-86E of Norman E. Green, but shortly afterward was attacked by the future top American ace of the Korean War, Captain Joseph C. McConnell. In the ensuing dogfight, they shot each other down, ejecting and being rescued safely.[32]

- 20 July 1953: During a raid deep into Manchuria, and after shooting down two Chinese MiGs, Majors Thomas M. Sellers and Stephen L. Bettinger (the second an ace with five kills) tried to catch by surprise two Soviet MiG-15s that were landing in Dapu. The Soviet fliers skillfully forced the Americans to overshoot, reversed direction and shot both down: Captain Boris N. Siskov forced Bettinger to bail out and his wingman 1st Lieutenant Vladimir I. Klimov killed Major Sellers. This was Siskov's fifth victory, making him the last ace of the Korean War. Those were also the last Sabres downed by Soviet fliers in the war.[26][38][40]

The MiG-15 threat forced the Far East Air Forces to cancel B-29 daylight raids in favor of night radar-guided missions from November 1951 onward. Initially, this presented a threat to Communist defenses, as their only specialized night-fighting unit was equipped with the prop-driven Lavochkin La-11, inadequate for the task of intercepting the B-29. Part of the regiment was re-equipped with the MiG-15bis, and another night-fighting unit joined the fray, causing American heavy bombers to suffer losses again. Between 21:50 and 22:30 on 10 June 1952, four MiG-15bis attacked B-29s over Sonchon and Kwaksan. Lieutenant Colonel Mikhail Ivanovich Studilin damaged a B-29A beyond repair, forcing it to make an emergency landing at Kimpo Air Base.[41] A few minutes later, Major Anatoly Karelin added two more Superfortresses to his tally.[13] Studilin and Karelin's wingmen, Major L. A. Boykovets and 1st Lieutenant Zhahmany Ihsangalyev, also damaged one B-29 each. Anatoly Karelin eventually became an ace with six kills (all B-29s at night).[42] In the aftermath of these battles, B-29 night sorties were cancelled for two months. Originally conceived to shoot down rather than escort bombers, both of America's state-of-art jet night fighters – the F-94 Starfire and the F3D Skyknight – were committed to protect the Superfortresses against MiGs.

The MiG-15 was less effective in getting past the Marine Corps ground-based two-seat F3D Skyknight night fighters assigned to escort B-29s after the F-94 Starfires proved ineffective. What the squat aircraft's lacked in sheer performance, they made up with the advantage of a search radar that enabled the Skyknight to see its targets clearly, while the MiG-15's directions to find bomber formations were of little use in seeing escorting fighters. On the night of 2–3 November 1952, a Skyknight with pilot Major William Stratton and radar operator Hans Hoagland damaged the MiG-15 of Captain V. D. Vishnyak. Five days later, Oliver R. Davis and radar operator D.F. "Ding" Fessler downed a MiG-15bis; the pilot, Lieutenant Ivan P. Kovalyov, ejected safely. Skyknights claimed five MiG kills for no losses of their own,[43] and no B-29s escorted by them were lost to enemy fighters.[44] However, the duel was not one-sided: on the night of 16 January 1953, an F3D almost did fall to a MiG, when the Skyknight of Captain George Cross and Master Sergeant J. A. Piekutowski suffered serious damage in an attack by a Soviet MiG-15bis; with difficulty, the Skyknight returned to Kunsan Air Base.[45] Three and a half months later, on the night of 29 May 1953, Chinese MiG-15 pilot Hou Shujun of the PLAAF shot down a F3D-2 over Anju; Sgt. James V. Harrell's remains were found on a beach during the summer of 2001 just miles from the Kunsan base. Captain James B. Brown is still missing in action.[27][46]

In a Royal Navy Sea Fury flying from a light fleet carrier[47] FAA pilot Lieutenant Peter "Hoagy" Carmichael downed a MiG-15 on 8 August 1952, in air-to-air combat. The Sea Fury would be one of the few piston-engined fighter aircraft following World War II's end to shoot down a jet fighter. On 10 September 1952, Captain Jesse G. Folmar shot down a MiG-15 with an F4U Corsair, but was himself downed by another MiG.[48]

The figures given by the Soviet sources indicate that the MiG-15s of the 64th IAK (the fighter corps that included all the divisions that rotated through the conflict) made 60,450 daylight combat sorties and 2,779 night ones and engaged the enemy in 1,683 daylight aerial battles and 107 at night, claiming to have shot down 1,097 UN aircraft over Korea, including 647 F-86s, 185 F-84s, 118 F-80s, 28 F-51s, 11 F-94s, 65 B-29s, 26 Gloster Meteors and 17 aircraft of different types.[38]

Chinese and Korean MiGs

The Soviet VVS and PVO were the primary users of the MiG-15 during the war, but not the only ones; it was also used by the PLAAF and KPAF (known as the United Air Army). Despite bitter complaints from the Soviet Union, which repeatedly requested the Chinese to accelerate the introduction of MiG-15 new units, the Chinese were relatively slow in this process at the time, and by 1951 there were only two regiments flying MiG-15bis as night fighters. Being not completely trained and equipped, both units were used only for the defence of China, but they became involved in interception of USAF reconnaissance aircraft, some of which went very deep over China.

By September 1951, with enough MiG-15s in the Yalu area, Soviet and Chinese leaders were confident enough to begin planning the deployment of Chinese and new North Korean MiG-15 regiments outside Chinese sanctuaries. Excluding a brief episode in January 1951, the PLAAF did not see action until 25 September 1951, when 16 MiG-15s engaged Sabres, with pilot Li Yongtai claiming a victory, but losing a MiG and its pilot.[49] The North Korean unit equipped with the MiG-15 got into action a year later, in September 1952. From then until the end of the war, the United Air Army claimed to have shot down 211 F-86s, 72 F-84s and F-80s, and 47 other aircraft of various types, losing 116 Chinese airmen and 231 aircraft: 224 MiG-15s, three La-11s and four Tupolev Tu-2s.[50] Several pilots were credited with five or more enemy aircraft, such as Zhao Baotong with seven victories, Wang Hai with nine kills, and both Kan Yon Duk and Kim Di San with five.

Based on Soviet archival data, 335 Soviet MiG-15s are known to have been admitted as lost over Korea.[51] Chinese claims of their losses amount to 224 MiG-15s over Korea.[52] North Korean losses are not known, but according to North Korean defectors their air force lost around 100 MiG-15s during the war.[53] Thus a total of 659 MiG-15s are admitted as being lost by all causes, while USAF claims of their losses amount to 78 F-86 Sabres in air-to-air combat[54] Overall UN losses to MiG-15s are credited as 78 F-86 Sabres and 75 aircraft of other types[54] However, one modern source claims that the USAF has more recently cited 224 losses (c.100 to air combat) out of 674 F-86s deployed to Korea.[55] Conversely, data-matching with Soviet records shows that US pilots routinely attributed their own combat losses to "landing accidents" and "other causes".[56] According to official US data ("USAF Statistical Digest FY1953"), the USAF lost 250 F-86 fighters in Korea: 184 were lost in combat (78 in air-combat, 19 by Anti-aircraft gun, 26 were "unknown causes" and 61 were "other losses") and 66 in incidents.[57]

More recent research by Dorr, Lake and Thompson has claimed the actual ratio is closer to 2 to 1.[58] The Soviets claimed to have downed over 600 Sabres,[59] together with the Chinese claims.[60] A recent RAND report[61] made reference to "recent scholarship" of F-86 v MiG-15 combat over Korea and concluded that the actual kill:loss ratio for the F-86 was 1.8 to 1 overall, and likely closer to 1.3 to 1 against MiGs flown by Soviet pilots.[62] However, this ratio were not count the number of aircraft of other types (B-29, A-26, F-80, F-82, F-84...) were shot down by MiG-15s.

Defection

In April 1951, a crashed MiG-15 was spotted near the Chongchon River. On 17 April 1951, a USAF Sikorsky H-19 staging through Baengnyeongdo carried a US/South Korean team to the crash site. They photographed the wreck and removed the turbine blades, combustion chamber, exhaust pipe and horizontal stabilizer. The overloaded helicopter then flew the team and samples back to Paengyong-do, where they were transferred to an SA-16 and flown south and then to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio, for evaluation.[63]

In July 1951, the submerged remains of a MiG-15 were spotted by Royal Navy carrier aircraft from HMS Glory. The MiG-15 was broken up, a piece of the engine was visible aft of the center section, and the tail section was located some distance away. The wreck was located in an area of mudbanks with treacherous tides and at the end of a narrow channel that was supposedly mined, ca. 160 km behind the front lines. The MiG-15 was retrieved, transported to Incheon and then to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

Eager to obtain an intact MiG for combat testing in a controlled environment, the United States launched Operation Moolah, which offered to any pilot who defected with his MiG-15, political asylum and a reward of US$100,000 (equivalent to $760,000 in 2018).[64][65] Franciszek Jarecki, a Polish Air Force pilot, defected from Soviet-controlled Poland in a MiG-15 on the morning of 5 March 1953, allowing Western air experts to examine the aircraft for the first time.[66] Jarecki flew from Słupsk to the field airport at Rønne on the Danish island of Bornholm. The whole trip took him only a few minutes. Specialists from the United States, called to the airfield by the Danish authorities, thoroughly examined the aircraft. According to international regulations, they then returned it by ship to Poland a few weeks later. Jarecki also received a $50,000 reward for being the first to present a MiG-15 to the Americans and became a US citizen.[N 1]

Following this example a total of four Polish MiG-15 pilots defected. No military maps showed foreign Baltic coastlines and so Franciszek Jarecki navigated using a basic school atlas, three of the four pilots managed to find the small island of Bornholm while one arrived at the Swedish Coast approximate 80km North of Bornholm.

A North Korean pilot, Lieutenant Kenneth H. Rowe (born No Kum-Sok) defected at Kimpo Air Base on 21 September 1953. After landing he claimed to be unaware of the US$100,000 reward.[68] This MiG-15 was minutely inspected and was test flown by several test pilots, including Chuck Yeager.[69] Yeager reported in his autobiography the MiG-15 had dangerous handling faults and claimed that during a visit to the USSR, Soviet pilots were incredulous he had dived in it, this supposedly being very hazardous.[70] Lieutenant No's aircraft is now on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force near Dayton, Ohio.

The Cold War

During the 1950s, the MiG-15s of the USSR and their Warsaw Pact allies on many occasions, intercepted aircraft of the NATO air forces performing reconnaissance near or inside their territory; such incidents sometimes ended with aircraft of one side or the other being shot down. The known incidents where the MiG-15 was involved include:

- 16 December 1950: A USAF RB-29 was downed over Primore (Sea of Japan) by two MiG-15 pilots, Captain Stepan A. Bajaev and 1st Lieutenant N. Kotov.

- 19 November 1951: MiG-15bis pilot 1st Lieutenant A. A. Kalugin forced a USAF C-47 that had penetrated Hungarian airspace to land at the airbase at Pápa.

- 13 June 1952: Two naval MiG-15s, flown by Captain Oleg Piotrovich Fedotov and 1st Lieutenant Ivan Petrovich Proskurin, shot down an RB-29A near Valentin Bay, over the Sea of Japan. All 12 crew members perished (their bodies were not recovered).

- 13 June 1952, Catalina affair: A Soviet MiG-15 flown by Captain Osinskiy shot down a Douglas DC-3 reconnaissance aircraft of the Swedish Air Force piloted by Alvar Almeberg near Ventspils over the Baltic Sea. All eight crew members perished. One of the two Swedish military Catalina flying boats that conducted subsequent search and rescue for the downed DC-3 was also shot down by a MiG-15, though with no loss of life.

- 7 August 1952: Two MiG-15 pilots, 1st Lieutenants Zeryakov and Lesnov, shot down a USAF RB-29 over the Kuril Islands. The entire crew of nine died (the remains of one, Captain John R. Durnham, were returned to the United States in 1993).

- 18 November 1952: Four MiG-15bis engaged four F9F-2 Panther off the aircraft carrier USS Oriskany (CV-34) near Vladivostok. One MiG-15 pilot, Captain Dmitriy Belyakov, managed to seriously damage Lieutenant Junior Grade David M. Rowlands's F9F-2, but seconds later he and 1st Lieutenant Vandalov were downed by Elmer Royce Williams and John Davidson Middleton. Neither Soviet pilot was found.

- 10 March 1953, Air battle over Merklín: Two MiG-15bis of the Czechoslovak Air Force intercepted two F-84Gs in Czechoslovak airspace. Lieutenant Jaroslav Šrámek shot down one of them; the F-84 crashed in Bavarian territory. The US pilot bailed out safely.

- 12 March 1953: Seven airmen were killed when the Royal Air Force Avro Lincoln they were flying in was shot down by a Soviet Air Force MiG-15 in the Berlin air corridor, near Boizenburg, 51 kilometres (32 mi) northeast of Lüneburg.

- 29 July 1953: Two MiG-15bis intercepted a RB-50G near Gamov, in the Sea of Japan, and instructed it to land at their home base. The RB-50 gunners opened fire and hit the MiG of 1st Lieutenant Aleksandr D. Rybakov. Rybakov and his wingman 1st Lieutenant Yuriy M. Yablonskiy then shot down the RB-50. One of the crew members (John E. Roche) was rescued alive, and three corpses were recovered. The remaining 13 crew members became missing-in-action.

- 17 April 1955: MiG-15 pilots Korotkov and Sazhin shot down an RB-47E north of the Kamchatka peninsula. All three crew members perished.

- 27 June 1955: El Al Flight 402 was shot down by two Bulgarian MiG-15 aircraft after penetrating Bulgarian airspace. All 58 passengers and crew perished in the attack.[71][72][73]

Suez Canal Crisis (1956)

Egypt bought two squadrons of MiG-15bis and MiG-17 fighters in 1955 from Czechoslovakia with the sponsorship and support of the USSR, just in time to participate in the Suez Canal Crisis. By the outbreak of the Suez conflict in October 1956, four squadrons of the Egyptian Air Force were equipped with the type, although few pilots were trained to fly them effectively.

They first saw aerial action on the morning of 30 October, intercepting four RAF Canberra bombers on a reconnaissance mission over the Canal Zone, damaging one. Later that day, MiG-15s attacked Israeli forces at Mitla Pass and El Thamed in the Sinai, destroying half a dozen vehicles. As a result, the Israeli Air Force (IAF) instituted a standing combat air patrol over the Canal, and the next attack resulted in two MiGs downed by IAF Mysteres, although the Egyptian aircraft were able to successfully hit the Israeli troops.

The next day, the MiGs evened the score somewhat when they badly damaged two IAF Ouragan fighters, forcing one of them to crash-land in the desert. British and French warplanes then began a systematic bombing campaign of Egyptian air bases, destroying at least eight MiGs and dozens of other Egyptian aircraft on the ground and forcing the others to disperse. The remaining aircraft still managed to fly some attack missions, but the Egyptians had lost air superiority.

During air combat against the IAF, Egyptian MiG-15bis managed to shoot down two Israeli aircraft: a Gloster Meteor F.8 on 30 October 1956, and a Dassault Ouragan on 1 November, which performed a belly landing — this last victory was scored by the Egyptian pilot Faruq el-Gazzavi. A third aircraft, a L-8 Piper Cub, was destroyed on the ground. [74]

An Egyptian MiG-15 was damaged, but the pilot managed to ditch in Lake Bardawil, and the aircraft was salvaged by Israeli forces.

Taiwan Straits crisis

After the Korean War ended, Communist China turned its attention back to Nationalist China on the island of Taiwan. Chinese MiG-15s were in action over the Taiwan Strait against the outnumbered Nationalist Air Force (CNAF), and helped make possible the Communist occupation of two strategic island groups. The US had been lending support to the Nationalists since 1951, and started delivery of F-86s in 1955. Sabres and MiGs clashed three years later in the Quemoy Crisis. Throughout the 1950s, MiG-15s of China's People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) frequently engaged Republic of China (ROC) and U.S. aircraft in combat; in 1958 a ROC F-86 fighter achieved the first air-to-air kill with an AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missile against a PLAAF MiG-15.[75]

Vietnam

Vietnam operated a number of MiG-15s and MiG-15UTIs for training only. There is no mention of the MiG-15 being involved in any combat against American aircraft in the early stages of the Vietnam War.

Other events

The first man in space, Yuri Gagarin, was killed in a crash during a March 1968 training flight in a MiG-15UTI due to poor visibility and miscommunication with ground control.[76]

MiG-17

The more advanced MiG-17 Fresco was very similar in appearance, but addressed many of the limitations of the MiG-15. It introduced a new swept wing with a "compound sweep" configuration: a 45° angle near the fuselage, and a 42° angle for the outboard part of the wings. The first prototype was flown in 1953 before the end of the Korean war. Later versions introduced radar, afterburning engines and missiles.

Production

The USSR built 1344 MiG-15, 8352 MiG-15bis and 3434 two-seaters. It was also built under license in Czechoslovakia as the S-102 (MiG-15, 821 aircraft), S-103 (MiG-15bis, 620 aircraft) and CS-102 (MiG-15UTI, 2012 aircraft) and Poland as the Lim-1 (MiG-15, 227 aircraft) and Lim-2 (MiG-15bis, 500 aircraft). No two-seaters have been built in Poland as such – the SB Lim-1 and SB Lim-2 variants were remanufactured from hundreds of Polish-, Czech- and Soviet-built single-seaters.

In the early 1950s, the Soviet Union delivered hundreds of MiG-15s to China, where they received the designation J-2. The Soviets also sent almost a thousand MiG-15 engineers and specialists to China, where they assisted China's Shenyang Aircraft Factory in building the MiG-15UTI trainer (designated JJ-2). China never produced a single-seat fighter version, only the two-seat JJ-2.[77] The number of JJ-2s built remains unknown and the estimates vary between 120 and 500 aircraft.

The designation "J-4" is unclear; some sources claim Western observers mistakenly labelled China's MiG-15bis a "J-4", while the PLAAF never used the "J-4" designation. Others claim "J-4" is used for MiG-17F, while "J-5" is used for MiG-17PF.[78] Another source claims the PLAAF used "J-4" for Soviet-built MiG-17A, which were quickly replaced by license-built MiG-17Fs (J-5s).[79]

Variants

- I-310

- Prototype.

- MiG-15

- First production version.

- MiG-15P

- Single-seat all-weather interceptor version of the MiG-15bis.

- MiG-15SB

- Single-seat fighter bomber version.

- MiG-15SP-5

- Two-seat all-weather interceptor version of the MiG-15UTI.

- MiG-15T

- Target-towing version.

- MiG-15bis

- Improved single-seat fighter version.

- MiG-15bisR

- Single-seat reconnaissance version.

- MiG-15bisS

- Single-seat escort fighter version.

- MiG-15bisT

- Single-seat target-towing version.

- MiG-15UTI

- Two-seat dual-control jet trainer.

- J-2

- (Jianjiji – fighter) Chinese designation of USSR production MiG-15bis single-seat fighter.[80]

- JJ-2

- (Jianjiji Jiaolianji – fighter trainer) Chinese production of MiG-15UTI two-seat jet trainers. Exported as Shenyang FT-2.[80]

- BA-5

- un-manned target drone conversions of J-2 fighters.[80]

- Lim-1

- MiG-15 jet fighters built under license in Poland.

- Lim-1A

- Polish-built reconnaissance version of the MiG-15 with AFA-21 camera.

- Lim-2

- MiG-15bis built under license in Poland, with Lis-2 (licensed VK-1) engines.

- Lim-2R

- Polish-built reconnaissance version of MiG-15bis with a place for a camera in the front part of the canopy.

- SB Lim-1

- Polish Lim-1 converted to equivalent of MiG-15UTI jet trainers, with RD-45 jet engines.

- SB Lim-2

- Polish Lim-2 or SBLim-1 converted to jet trainers with Lis-1 (VK-1) jet engines.

- SBLim-2A

- Polish-built two-seat reconnaissance version, for correcting artillery.

- S-102

- MiG-15 jet fighters built under license in Czechoslovakia, with M05 (licensed RD-45) Motorlet/Walter engines.

- S-103

- MiG-15bis jet fighters built under license in Czechoslovakia with M06 (licensed VK-1) Motorlet/Walter engines.

- CS-102

- MiG-15UTI jet trainers built under license in Czechoslovakia.

Foreign reporting names

- Fagot

- The NATO reporting name for the single-seat MiG-15[81]

- Midget

- The NATO reporting name for the two-seat MiG-15UTI[82]

Operators

Current operators

- Korean People's Army Air Force[83]

Former operators

- People's Air and Air Defence Force of Angola

- Congolese Air Force

- Guinea Air Force

- Mali Air Force

- Mongolian People's Army Air Force

- Tanzanian Air Force

- Ugandan People's Defence Air Force

- United States Air Force – In the 1980s, the United States purchased a number of Shenyang J-4s along with Shenyang J-5s from China via the Combat Core Certification Professionals Company; these aircraft were employed in a "mobile threat test" program at Kirtland Air Force Base, operated by the 4477th "Red Hats" Test and Evaluation Squadron of the United States Air Force. As of 2015 MiG-15UTI's and MiG-17's are operated by a civilian contractor at both the USAF and US Naval Test Pilot Schools for student training.

Civilian operators

- One private Czechoslovak-built CS-102 that was operated by the Polish Air Force. Rebuilt in 1975 as a SB Lim2M. It was brought to Argentina in 1997 and given the experimental registration LV-X216.[84][85]

Surviving aircraft

Many MiG-15s are on display throughout the world. In addition, they are becoming increasingly common as private sport aircraft and warbirds. According to the FAA, there were 43 privately owned MiG-15s in the US in 2011, including Chinese and Polish derivatives, the first of which is owned by aviator and aerobatic flyer, Paul T. Entrekin.[86]

- Australia

- As of July 2015, six privately owned MiG-15s are airworthy and on the Australian civil aircraft register. At least seven others are on static display in museums, including one in the Australian War Memorial.

- Bulgaria

- One MiG-15 is on display in Sofia at the National Museum of Military History.

- Canada

- A flying MiG-15UTI is operated at Region of Waterloo International Airport by Waterloo Warbirds:One LiM-2 (MiG-15bis) serial number 1B00316 is on display at Canada Aviation and Space Museum. A Czechoslovakian MiG-15bisSB serial number 713133 is on display at Edenvale Airport near Edenvale, Ontario, Canada.[87]

- China

- Several MiG-15s (including some in North Korean colours) are preserved at the China Aviation Museum outside Beijing.

- Cuba

- A MiG-15UTI of the FAR (Fuerza Aérea Revolucionaria) is displayed at the Museo del Aire.

- Czech Republic

- In 2014 one two seat version of MiG-15 was restored into airworthy condition in Hradec Králové. One Czechoslovakian built Mig-15 (S-102, built 1953) serial number 231720 is on display in Kbely Aviation Museum in Prague.[88]

- Finland

- Three MiG-15UTIs survive: one in Päijänne Tavastia Aviation Museum in Lahti, one in Hallinportti Aviation Museum at Kuorevesi and one in Central Finland Aviation Museum in Jyväskylä. The Finnish nickname of the aircraft was Mukelo ("Ungainly"), after the FinnAF aircraft type designation code MU.

- France

- One MiG-15bis is on display on the campus of the ISAE-Supaero school in Toulouse.[89]

- Norway

- MiG-15UTI "RED 18"

This aircraft is a Polish-built SB Lim-2 (MiG-15UTI), produced by WSK-Mielec in 1952. The aircraft is operated by the Norwegian Air Force.

- Poland

- FlyFighterJet.com offers a SB Lim-2/MiG-15UTI for adventure flights in Poland[90]

A MiG-15 is parked adjacent to the terminal building at what is now Zielona Góra Airport, near Babimost, Poland, reflecting the former airport's military origins.[91]

- Romania

- A few Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 are on display in Romania

- 244 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15is Ex FAR in Bucharest, Romania at the Army Museum.

- 246 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 Ex FAR Museum, outside at Bucharest – Aviation Museum, Romania

- 2543 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 UTI Ex FAR Museum, outside at Bucharest – Aviation Museum, Romania

- 2579 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 UTI Ex FAR Museum, outside at Bucharest – Aviation Museum, Romania

- 2713 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 bis Ex FAR Museum, outside at Bucharest – Aviation Museum, Romania

- 727 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 Ex FAR Museum, outside at Bucharest – Aviation Museum, Romania

- 766 Mikoyan – Gurevich MiG-15 Ex FAR Preserved at Ianca

- A MiG-15 is on display in the front yard of Traian Vuia Lyceum in Craiova. Google maps coordinates 44.309248, 23.812195

- Sweden

- Lim-1 – Displayed at Swedish Air Force Museum

- United Kingdom

- A Polish-built MiG-15 is displayed in North Korean colours at the Fleet Air Arm Museum.

- An S-103 in Czechoslovakian colours is displayed at the National Museum of Flight, East Fortune, Edinburgh.

- A Mig-15bis (1120) in Polish colours is on display at Royal Air Force Museum Cosford.

- United States

.jpg)

.jpg)

- A North Korean MiG-15 (c/n 2015357) is on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. This is the aircraft flown to Kimpo Air Base in South Korea on 21 September 1953 by a defecting North Korean pilot who was given a reward of $100,000 (see above). The aircraft was flight-tested on Okinawa and then brought to the U.S. to be returned to its "rightful owners" (believed to be the Soviet Union, which denied participating in the Korean War).[64] When this offer was ignored it was transferred to the NMUSAF in November 1957.[92] It is on display in the museum's Korean War Gallery.[93]

- A MiG-15 is on display at the National Naval Aviation Museum, NAS Pensacola, Florida.[94]

- A MiG-15 operated by the People's Liberation Army Air Force is on display at The Museum of Flight in Seattle, WA

- A MiG-15bis is on display at the Flying Leatherneck Aviation Museum located at Marine Corps Air Station Miramar in San Diego, California.

- There is a MiG-15bis, number 83227, undergoing a restoration at the New England Air Museum, Bradley International Airport, Windsor Locks, CT.[95]

- A Polish built LiM-2 (MiG-15bis) Serial number: 1B01016 (FAA Reg. Number N15YY) is on display at the Combat Air Museum in Topeka, KS

- Two MiG-15UTI are operated by Red Star Aviation on behalf of the US Naval Test Pilot School and the US Air Force Test Pilot School, located at Patuxent River Naval Air Station and Edwards Air Force Base respectively. One is a former Polish sBLim-2art(m) and another is a Czechoslovakian manufactured CS-102, ex Romanian AF. These aircraft are used to train test pilots from the US and other nations sending students to the two schools.

- A MiG-15 is located at the Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham–Shuttlesworth International Airport, Birmingham, Alabama.

- A Chinese version of the MiG-15bis is on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum at Washington Dulles International Airport, Virginia[96]

- A MiG-15UTI is on display at the Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum, Titusville, Florida[97]

- A MiG-15 is on display at the Minnesota Air National Guard Museum, Minneapolis–St. Paul International Airport, Minnesota[98]

- A MiG-15 is on static display at the Commemorative Air Force Museum in Mesa, Arizona[99]

- North Korean MiG-15 079 under restoration at Palm Springs Air Museum, Palm Springs, California

- A MiG-15 is on display at the Naval Air Station Wildwood Aviation Museum at Cape May airport in Cape May, New Jersey

- A MiG 15 is on display in front of an antique shop in Forney, Texas.

- Soviet built Mig-15bis serial #2292 built in 1954 and supplied to China as a J-2 Mig-15 is on indoor display at the Oakland Aviation Museum Oakland, California.

Specifications (MiG-15bis)

Data from OKB Mikoyan[100], MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design[101]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 10.102 m (33 ft 2 in)

- Wingspan: 10.085 m (33 ft 1 in)

- Height: 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in)

- Wing area: 20.6 m2 (222 sq ft)

- Airfoil: root: TsAGI S-10 ; tip: TsAGI SR-3[102]

- Empty weight: 3,681 kg (8,115 lb)

- Gross weight: 5,044 kg (11,120 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 6,106 kg (13,461 lb) with 2x600 l (160 US gal; 130 imp gal) drop-tanks

- Fuel capacity: 1,420 l (380 US gal; 310 imp gal) internal

- Powerplant: 1 × Klimov VK-1 centrifugal-flow turbojet, 26.5 kN (5,950 lbf) thrust

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,076 km/h (669 mph, 581 kn) at sea level

- 1,107 km/h (688 mph; 598 kn) / M0.9 at 3,000 m (9,843 ft)

- Maximum speed: Mach 0.87 at sea level

- Cruise speed: 850 km/h (530 mph, 460 kn) Mach 0.69

- Ferry range: 2,520 km (1,570 mi, 1,360 nmi) at 12,000 m (39,370 ft) with 2x600 l (160 US gal; 130 imp gal) drop-tanks

- Service ceiling: 15,500 m (50,900 ft)

- Rate of climb: 51.2 m/s (10,080 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 296.4 kg/m2 (60.7 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.54

Armament

- Guns: **2 × 23 mm Nudelman-Rikhter NR-23 autocannon in the lower left fuselage (80 rounds per gun, 160 rounds total)

- 1 × 37 mm Nudelman N-37 autocannon in the lower right fuselage (40 rounds total)

- Hardpoints: 2 with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Bombs: 100 kg (220 lb) bombs

- Other: drop tanks, or unguided rockets

See also

Related development

- Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17

- Raduga KS-1 Komet

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Arsenal VG 70

- Canadair Sabre

- Dassault Ouragan

- FMA IAe 33 Pulqui II

- Grumman F9F Panther

- Hawker P.1052

- Lavochkin La-15

- McDonnell F2H Banshee

- North American F-86 Sabre

- Saab 29 Tunnan

- Supermarine Attacker

- Yakovlev Yak-30 (1948)

Related lists

References

Notes

- According to a thesis published by Coleman Armstrong Mehta in 2006, Yugoslavia provided the CIA with a MiG-15 in flying condition as early as November 1951.[67]

Citations

- "Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (Ji-2) Fagot B.", Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, archived from the original on 20 December 2015

- Belyakov and Marmain 1994, pp. 81, 88.

- Gordon, Yefim. Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15. Leicester, UK: Midland Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-105-9.

- "MiG-15." Military Factory. Retrieved: 11 July 2012.

- The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 Archived 20 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine. plane-crazy.net

- Fitzsimons 1985, p. 11.

- Belyakov and Marmain 1994, pp. 112, 114.

- Gunston 1995, p. 188.

- Gunston 1995, p. 189.

- Belyakov and Marmain 1994, p. 120.

- Yefim Gordon

- Joiner, Stephen, "MiG!", Air & Space, December 2013/January 2014, p.45

- Krylov, Leonid and Tepsurkaev, Yuriy. Soviet MiG-15 Aces of the Korean War", Chapter 1. Korean War Resources (KORWALD). Retrieved: 11 March 2009.

- "Historic Battles." historic-battles.com. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- "Korean Air Force." Archived 8 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine korean-war.com. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- Aldrich, Richard J. (July 1998). "British Intelligence and the Anglo-American 'Special Relationship' during the Cold War". Review of International Studies. 24 (3): 331–351. doi:10.1017/s0260210598003313. JSTOR 20097530.

- Zampini, Diego. "Russian [sic-Soviet] Aces over Korea Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 Fagot pilots". Acepilots.com, 2008. Retrieved: 10 March 2009.

- Zaloga 1991

- Krylov and Tepsurkaev 2009

- "Sabre: The F-86 in Korea." findarticles.com. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- Common misspelling in the English-language sources is Vorovyov, but the correct spelling is Vorobyov, as confirmed, e.g. here: "Soviet Aces of the Korean War 1950–1953 (in Russian: Советские асы Корейской войны 1950–1953 гг.)". Retrieved 10 July 2013.

- "William F. (Bill) Welch — 31st and 91st SRS Recollections". rb-29.net. Archived from the original on 22 June 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- Thompson and McLaren 2002, Chapter 10.

- Nosatov, Victor Ivanovich. "Черный четверг" стратегической авиации США ("Black Thursday" of US strategic aviation) (in Russian). nvo.ng.ru, 25 May 2005. Retrieved: 11 December 2011.

- Seydov, Igor. "Dmitriy Samoylov", Mir Aviatsiya, 1–2003, pp. 30–36.

- Thompson and McLaren 2002, Appendix B.

- KORWALD Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- Davis 2001, p. 91.

- Krylov and Tepsurkaev 2008, Chapter 1.

- Zampini, Diego. "Red Stars over North Korea". Flieger Revue Xtra 22, November 2008.

- Zampini, Diego. "Red Stars over North Korea". Flieger Revue Xtra 22, November 2008

- Seydov, Igor and Askold German. "Krasnye Dyaboly na 38-oy Parallel." Moskow: EKSMO, 1998.

- Zampini, Diego. "Red Stars over North Korea", Flieger Revue Xtra 23, December 2008

- Dorr et al. 1995, Chapter 3.

- Zhang 2003, pp 167–168.

- "Capt. Clifford D. Jolley". Archived from the original on 11 July 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- "Jolley". ejection-history.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Krylov and Tepsurkaev 2008, Chapter 6.

- Zhang 2003, pp. 192, 265.

- Zampini, Diego. "Red Stars over North Korea", Flieger Revue Xtra 23, November 2008

- Seydov, Igor and German, Askold. KORWALD 1998.

- Krylov and Tepsurkaev 2008, Appendixes.

- Grossnick, Roy A. and William J. Armstrong. United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Historical Center, 1997. ISBN 0-16-049124-X.

- Gobel, Greg. "The Douglas F3D Skyknight." Archived 13 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Vectorsite, 1 August 2008. Retrieved: 2 May 2009.

- Dorr et al. 1995, p. 71.

- Zhang 2002, pp. 194–195.

- "Sea Fury History". Unlimited Air Racing. Retrieved: 9 March 2007.

- Flight Journal Aug 2002 Corsairs to the rescue

- Zhang 2002, Chapter 7.

- Zhang 2002, Chapter 9.

- Igor Seidov and Stuart Britton. Red Devils over the Yalu: A Chronicle of Soviet Aerial Operations in the Korean War 1950–53 (Helion Studies in Military History). Helion and Company 2014. ISBN 978-1909384415. Page: 554.

- Zhang, Xiaoming. Red Wings over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union, and the Air War in Korea (Texas A&M University Military History Series). College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University, 2002. ISBN 978-1-58544-201-0.

- Kum-Suk No and J. Roger Osterholm. A MiG-15 to Freedom: Memoir of the Wartime North Korean Defector who First Delivered the Secret Fighter Jet to the Americans in 1953. McFarland, 2007. ISBN 978-0786431069. Page 142.

- http://www.dpaa.mil/portals/85/Documents/KoreaAccounting/korwald_all.pdf

- Cold War Battle in the Sky: F-86 Saber vs. Mig-15 Archived 3 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Welcome to the Air Combat Information Group". Archived from the original on 4 June 2013.

- USAF losses during the Korean War. USAF Statistical Digest FY1953

- Dorr, Robert F., Jon Lake and Warren E. Thompson. Korean War Aces. London: Osprey Publishing, 2005. ISBN 1-85532-501-2.

- Sewell, Stephen L. "Russian Claims from the Korean War 1950–53." Archived 1 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine korean-war.com. Retrieved: 19 July 2011.

- Zhang, Xiaoming. Red Wings over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union, and the Air War in Korea. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 2002. ISBN 1-58544-201-1.

- Stillion, John and Scott Perdue. "Air Combat Past, Present and Future." Archived 6 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine Project Air Force, Rand, August 2008. Retrieved 11 March 2009.

- Igor Seidov and Stuart Britton. Red Devils over the Yalu: A Chronicle of Soviet Aerial Operations in the Korean War 1950–53 (Helion Studies in Military History). Helion and Company 2014. ISBN 978-1909384415. Page: 554.

- Werrell, Kenneth (2005). Sabres over MiG Alley: the F-86 and the battle for air superiority in Korea. Naval Institute Press. pp. 95–6. ISBN 9781591149330.

- Friedman, Herbert A. "Operation Moolah: The Plot to Steal a MiG-15". psywarrior.com. Retrieved: 29 November 2011.

- Thomas, Ryland; Williamson, Samuel H. (2019). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 6 April 2019. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the Measuring Worth series.

- Albury, Chuck. "Escape from Red Poland." St. Petersburg Times, 5 March 1967. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Mehta, Coleman Armstrong. "A Rat Hole to be Watched? CIA Analyses of the Tito-Stalin Split, 1948–1950." lib.ncsu.edu. Retrieved: 22 November 2010.

- Kum-Sok and Osterholm 1996

- We flew the MiG. USAF. 1953.

- Yeager and Janos 1986, p. 208.

- Magnus, Allan. "Shootdowns of the Cold War Era" Air Aces, 28 July 2002. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Kotlobovsky, Alexander. "Goryachoe Nebo Kholodnoy Voyny" ("The Hot Sky of the Cold War" (in Russian)) airforce.ru, 2005. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Lednicer, David. "Aircraft Downed During the Cold War and Thereafter." silent-warriors.com, 8 November 2005. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Nicolle 1996, p.159

- "AAM-N-7/GAR-8/AIM-9 Sidewinder." Raytheon (Philco/General Electric). designation-systems.net. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- Doran 1998, pp. 210–229.

- "China." globalsecurity.org. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- "China." designation-systems.net. Retrieved: 11 July 2012.

- "Background." Archived 26 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine airtoaircombat.com. Retrieved: 12 September 2010.

- Gordon and Komissarov 2008

- 4.3 F – Fighters. designation-systems.net

- "Designations of Soviet and Russian Military Aircraft and Missiles". Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Trade Registers".

- "Un MiG-15 en Argentina (MiG-15 SB LIM2 UTI)" (in Spanish). 13 June 2010.

- "Pablo volando mig 15" (in Spanish). YouTube.

- "FAA Registry: MiG-15". FAA. Retrieved 17 May 2011.

- http://www.roadsideattractions.ca/popfiles/edenvale.htm%5B%5D

- "Vhu Praha".

- "Aviation Photo #2120860: Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15bis - Czech Republic - Air Force".

- The First MiG-15 Flight in Europe – Fly a legend! flyfighterjet.com.

- Google Maps image, accessed 2018-08-28

- United States Air Force Museum 1975, p. 57.

- "National Museum of the U.S. Air Force." Retrieved 2 February 2018

- "MiG-15." National Naval Aviation Museum. Retrieved: 7 November 2017.

- MiG-15bis 'Fagot B'. neam.org

- "Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (Ji-2) Fagot B." Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. Retrieved: 13 September 2015.

- "VAC Aircraft Inventory." Archived 29 July 2015 at the Wayback Machine Valiant Air Command Warbird Museum. Retrieved: 13 September 2015.

- "MiG-15 MIDGET". Minnesota Air National Guard Museum. Retrieved: 13 September 2015.

- "Mikoyan & Gurevich MiG 15 bis and UTI Trainer". Commemorative Air Force. Retrieved: 18 October 2016.

- Gordon, Yefim; Komissarov, Dmitry (2009). OKB Mikoyan. Hinkley: Midland Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85780-307-5.

- Belyakov and Marmain, pp. 138-142

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

Bibliography

- Belyakov, R.A. and J. Marmain. MiG: Fifty Years of Secret Aircraft Design. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing, 1994. ISBN 1-85310-488-4.

- Butowski, Piotr (with Jay Miller). OKB MiG: A History of the Design Bureau and its Aircraft. Earl Shilton, Leicester, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1991. ISBN 0-904597-80-6.

- Davis, Larry. 4th Fighter Wing in the Korean War. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-0-7643-1315-8.

- Davis, Larry. MiG Alley Air to Air Combat over Korea. Warren, Michigan: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1978. ISBN 0-89747-081-8.

- Doran, Jamie and Piers Bizony. Starman: The Truth Behind the Legend of Yuri Gagarin. London: Bloomsbury Publishing plc, 1998. ISBN 0-7475-3688-0.

- Dorr, Robert F., Jon Lake and Warren Thompson. Korean War Aces(Aircraft of the Aces). London: Osprey Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-1-85532-501-2.

- Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. "MiGs." Modern Fighting Aircraft. Fallbrook, California: Arco Publishing, 1985. ISBN 0-668-06070-0

- Gordon, Yefim and Peter Davison. Mikoyan Gurevich MiG-15 Fagot (WarbirdTech Volume 40). North Branch, Minnesota: Speciality Press, 2005. ISBN 1-58007-081-7.

- Gordon, Yefim and Vladimir Rigmant. Warbird History: MiG-15 – Design, Development, and Korean War Combat History. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks, 1993. ISBN 978-0-87938-793-8.

- Gordon, Yefim et al. MiG-15 Fagot, all variants (bilingual Czech/English). Prague 10-Strašnice: MARK I Ltd., 1997. ISBN 80-900708-6-8.

- Gordon, Yefim and Dmitry Komissarov. Chinese Aircraft. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-1-902109-04-6.

- Gunston, Bill. The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft: 1875–1995. London: Osprey Aerospace, 1996. ISBN 1-85532-405-9.

- Higham, Robin, John T. Greenwood and Von Hardesty. Russian Aviation and Air Power in the Twentieth Century. London: Frank Cass, 1998. ISBN 978-0-7146-4380-9.

- Karnas, Dariusz. Mikojan Gurievitch MiG-15. Sandomierz, Poland/Redbourn, UK: Mushroom Model Publications, 2004. ISBN 978-83-89450-05-0.

- Krylov, Leonid and Yuriy Tepsurkaev. "Combat Episodes of the Korean War". Mir Aviatsiya (Translation to English language by Stephen L. Sewell), 1–97, pp. 38–44. Retrieved: 29 March 2009.

- Krylov, Leonid and Yuriy Tepsurkaev. Soviet MiG-15 Aces of the Korean War. Botley, Oxford, UK: Osprey Publications, 2008. ISBN 1-84603-299-7.

- Kum-Suk, No and Roger J. Osterholm. A MiG-15 to Freedom. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0-7864-0210-5.

- Mesko, Jim. Air War over Korea. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 2000. ISBN 0-89747-415-5.

- Nicolle, David. Phoenix over the Nile: A History of Egyptian Air Power 1932–1994 (Smithsonian History of Aviation & Spaceflight). Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian, 1996. ISBN 1-56098-626-3.

- Seydov, Igor and Askold German. Krasnye Dyaboly na 38-oy Parallel. EKSMO, Russia. 1998.

- Stapfer, Hans-Heiri. MiG-15 Fagot Walk Around (Walk Around 40). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 2006. ISBN 0-89747-495-3.

- Stapfer, Hans-Heiri. MiG-15 in action (Aircraft number 116). Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications Inc., 1991. ISBN 0-89747-264-0.

- Sweetman, Bill and Bill Gunston. Soviet Air Power: An Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Warsaw Pact Air Forces Today. London: Salamander Books, 1978. ISBN 0-517-24948-0.

- Thompson, Warren E. and David R. McLaren. MiG Alley: Sabres vs. MiGs over Korea. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1-58007-058-4.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation, 1975.

- Werrell, Kenneth. Sabres Over MiG Alley: The F-86 and the Battle for Air Superiority in Korea. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1-59114-933-0.

- Wilson, Stewart. Legends of the Air 1: F-86 Sabre, MiG-15 and Hawker Hunter. London: Aerospace Publications Pty Ltd., 2003. ISBN 1-875671-12-9.

- Yeager, Chuck and Leo Janos. Yeager: An Autobiography. New York: Bantam Books, 1986. ISBN 0-553-25674-2.

- Zaloga, Steven J. "The Russians in MiG Alley: Their part in the Korean War." Air Force Magazine, Volume 74, Issue 2, February 1991.

- Zhang, Xiaoming. Red Wings over the Yalu: China, the Soviet Union, and the Air War in Korea (Texas A&M University Military History Series). College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University, 2002. ISBN 978-1-58544-201-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15. |

- Noland, David. Fighter Planes: MiG-15. The Air Power of the Evil Empire

- The Mikoyan MiG-15 at Greg Goebel's AIR VECTORS

- Warbird Alley: MiG-15 page- Information about privately owned MiG-15s

- MiG-15 in Korea

- MiG-15 Fagot at Global Security.org

- MiG-15 Fagot at Global Aircraft

- MiG-15 Fagot at FAS

- Cuban MiG-15

- MiG Alley USA, Aviation Classics, Ltd Reno, Nevada

.png)