No Kum-sok

Kenneth H. Rowe (born No Kum-sok; Korean: 노금석; January 10, 1932)[1] is a Korean American engineer and aviator who served as a senior lieutenant in the Korean People's Army Air and Anti-Air Force during the Korean War.[2][3] Approximately two months after the end of hostilities, he defected to South Korea in a MiG-15 aircraft, and was subsequently granted political asylum in the United States.[4]

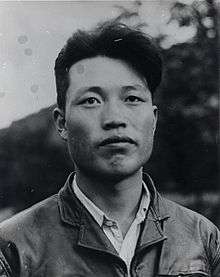

No Kum-sok | |

|---|---|

No in the early 1950s | |

| Native name | |

| Birth name | No Kum-sok |

| Nickname(s) | "Okamura Kyoshi" |

| Born | January 10, 1932 Shinko, Kankyōnandō, Japanese Korea (now Sinhung County, South Hamgyong Province, North Korea) |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1949–1953 |

| Rank | Senior lieutenant |

Early life and education

No was born in Sinhung County, South Hamgyong Province, in then-Japanese occupied northern Korea. Under colonial rule, No was required to adopt a Japanese name - Okamura Kyoshi.[5]

His father was a baseball player for a company's team. During World War II, No supported Japan and considered becoming a kamikaze pilot, but his father was adamantly against it. No's support for Imperial Japan waned and he became pro-American, though he had to hide his pro-Americanism due to the dangers of being recognized as being an admirer of the U.S. in northern Korea at the time.

In early 1948, a teenage No attended a speech by Kim Il-sung. Though No was opposed to Communism, he found Kim to be a capable orator.[6] However, No had to keep his anti-Communist views hidden, due to the danger of what would happen if North Korean authorities had found out about them.

Career

Korean War

During the Korean War, No applied to join the Korean People's Navy and was accepted after he lied in the selection test. At the naval academy, No won favor of his history professor who later helped No in the pilot selection test. After passing the selection test, No was promoted to ensign, and brought to Manchuria for flight training. He subsequently received promotion to the rank of lieutenant and then to senior lieutenant. He flew more than 100 combat missions during the war.[7]

Defection

On the morning of September 21, 1953, No flew his Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 from Sunan just outside Pyongyang to the Kimpo Air Base in South Korea.[8][9] The time from take-off in North Korea to landing in South Korea was 17 minutes, with the MiG reaching 1000 km/h (620 mph).[10] During the flight, he was not chased by North Korean aircraft (as he was too far away), nor was he interdicted by American air or ground forces;[10] U.S. radar near Kimpo had been shut down temporarily that morning for routine maintenance.[11] No landed the wrong way on the runway, almost hitting an F-86 Sabre jet landing at the same time from the opposite direction.[9][10] Captain Dave William veered out of the way and exclaimed over the radio "It's a goddamn MiG!".[10] Another American pilot, Captain Jim Sutton, who was circling the airport, said that if No had tried to land in the right direction, he would have been spotted and shot down.[10] No taxied the MiG into a free parking spot between two Sabre jets, got out of the plane and began tearing up a picture of Kim Il-sung that was placed in the cockpits of North Korean aircraft, and then threw up his arms in surrender at approaching airbase security guards.[10]

After being taken into custody and debriefed by CIA operative "Andy Brown" (born Arseny Yankovsky, son of Yuri Yankovsky), No received a $100,000 (equivalent to $955,597 in 2019) reward offered by Operation Moolah for being the first pilot to defect with an operational aircraft, which he said he never heard of prior to his defection.[12] No explained that North Korean pilots were not allowed to listen to South Korean radio, the leaflets broadcasting the award were not dropped in Manchuria where the pilots were based, and even if they had heard about the reward the amount of money would have been meaningless to the young Communists; he said the program would have been more effective if they had offered a good job and residence in North America. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was against paying defectors.[13]

There were repercussions for No's defection. According to Captain Lee Un-yong, a Korean People's Army Air and Anti-Air Force flight instructor who defected to South Korea two years after No, General Wan-yong, the top commander of the Korean People's Army Air and Anti-Air Force, was demoted, and five of No's air force comrades and commanders were executed.[14] One of those killed was Lieutenant Kun Soo-sung, No's best friend and fellow pilot.[14] No's father was already dead and his mother already defected to the South; however, he had an uncle and the fate of him and the rest of his family was never known.[14]

No's MiG-15

After No surrendered his aircraft, it was taken to Okinawa, where it was given USAF markings and test-flown by Captain H.E. Collins and Major Chuck Yeager. The MiG-15 was later shipped to Wright-Patterson Air Force Base after attempts to return it to North Korea were unsuccessful.[8] It is currently on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force.

Post-defection life

In 1954, No emigrated to the United States and even met then-Vice President Richard Nixon. After immigrating, he anglicized his name to "Kenneth H. Rowe".[1] He was joined in the U.S. by his mother, who had been evacuated from North Korea earlier in 1951. He subsequently graduated from the University of Delaware, with degrees in mechanical and electrical engineering.[11] He married an émigré from Kaesong, North Korea, they raised two sons and a daughter, and he became a U.S. citizen.[11] He worked as an aeronautical engineer for Grumman, Boeing, Pan Am, General Dynamics, General Motors, General Electric, Lockheed, DuPont, and Westinghouse.[11][12][15]

In 1970, he learned from a fellow defector that, as punishment for his defection, his best friend, Lieutenant Kun Soo Sung, had been executed. He learned that four other pilots in his chain of command were also executed by firing squad. One of the pilots and a friend in his squadron became the General of the Korean People's Army. General O Kuk-ryol, who became the vice chairman of the National Defence Commission in 2009, was considered the second most powerful man in North Korea.[11][12]

In 1996, he wrote and published a book, A MiG-15 to Freedom,[1] about his defection and previous life in North Korea. Rowe retired in 2000 after working 17 years as an aeronautical engineering professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University.[11][16] A biography of No by Blaine Harden was published in 2015 as The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Tyrant Who Created North Korea and The Young Lieutenant Who Stole His Way to Freedom.[17] Harden had access to newly released intelligence, and to No.[18]

Personal life

Rowe speaks fluent English and currently lives in Daytona Beach, Florida; he has stated that he does not regret his decision to defect from North Korea to South Korea.

References

- Rowe, Kenneth H. (No Kum-sok); Osterholm, J. Roger (1996). A MiG-15 to Freedom. McFarland & Company Inc. ISBN 0-7864-0210-5. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- "This Florida man escaped from North Korea in a MiG-15 fighter jet". Public Radio International. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- "Air Force Magazine". www.airforcemag.com. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- "America's $100,000 Deal with a North Korean Defector". POLITICO Magazine. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- http://www.pri.org/stories/2015-03-17/florida-man-escaped-north-korea-mig-15-fighter-jet

- 2015 interview

- Richard Conn (July 27, 2013). "Former MiG pilot remembers flight to freedom". The Daytona Beach News-Journal.

- "The Story of the MiG-15 On Display". Factsheets. National Museum of the United States Air Force. May 12, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2016.

- "The MiG-15's role during the Korean War". March 14, 2015. Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Harden (2015), Chapter 11, Part 3

- Lowery, John (July 2012). "Lt. No". Air Force Magazine. The Air Force Association. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- "PsyWarrior.com "Operation Moolah - The Plot To Steal A MIG-15"". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- Harden (2015), Chapter 11, Part 5

- Harden (2015), Chapter 11, Part 4

- "Leadership." Red Star Aviation. Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Zenobia, Keith (September 2004). "Ken Rowe, a.k.a. No Kum-Sok: A MiG-15 to Freedom" (PDF). 19 (9). Pine Mountain Lakes Aviation Association Newsletter: 1. Retrieved September 22, 2013. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Terry Hong (March 19, 2015). "'The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot' presents a riveting slice of North Korean history". Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

- "The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Tyrant Who Created North Korea and the Young Lieutenant Who Stole His Way to Freedom". Publishers Weekly. Retrieved March 21, 2015.

Bibliography

- Blaine Harden (2015). The Great Leader and the Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Tyrant Who Created North Korea and The Young Lieutenant Who Stole His Way to Freedom. Viking. ISBN 978-0670016570.

External links