AIM-9 Sidewinder

The AIM-9 Sidewinder (for Air Intercept Missile) is a short-range air-to-air missile which entered service with the US Navy in 1956 and subsequently was adopted by the US Air Force in 1964. Since then the Sidewinder has proved to be an enduring international success, and its latest variants are still standard equipment in most western-aligned air forces.[4] The Soviet K-13, a reverse-engineered copy of the AIM-9, was also widely adopted by a number of nations.

| AIM-9 Sidewinder | |

|---|---|

_copy.jpg) AIM-9L | |

| Type | Short-range air-to-air missile |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1956–present |

| Production history | |

| Manufacturer | Raytheon Company[1] Ford Aerospace Loral Corp. |

| Unit cost | US$603,817[2] (AIM-9X Blk II FY15). US$472,000[3] (AIM-9X FY 2019) |

| Produced | 1953-present |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 188 pounds (85.3 kg)[1] |

| Length | 9 feet 11 inches (3.02 m)[1] |

| Diameter | 5 in (127.0 mm)[1] |

| Warhead | WDU-17/B annular blast-frag[1] |

| Warhead weight | 20.8 lb (9.4 kg)[1] |

Detonation mechanism | IR proximity fuze |

| Engine | Hercules/Bermite Mk. 36 Solid-fuel rocket |

| Wingspan | 11 in (279.4 mm) |

Operational range | 0.6 to 22 miles (1.0 to 35.4 km) |

| Maximum speed | Mach 2.5+[1] |

Guidance system | Infrared homing (most models) semi-active radar homing (AIM-9C) |

Launch platform | Aircraft, naval vessels, fixed launchers, and ground vehicles |

Low-level development started in the late 1940s, emerging in the early 1950s as a guidance system for the modular Zuni rocket.[5][6] This modularity allowed for the introduction of newer seekers and rocket motors, including the AIM-9C variant, which used semi-active radar homing and served as the basis of the AGM-122 Sidearm anti-radar missile. Originally a tail-chasing system, early models saw extensive use during the Vietnam War but had a low success rate. This led to all-aspect capabilities in the L version which proved to be an extremely effective weapon during combat in the Falklands War and the Operation Mole Cricket 19 ("Bekaa Valley Turkey Shoot") in Lebanon. Its adaptability has kept it in service over newer designs like the AIM-95 Agile and SRAAM that were intended to replace it.

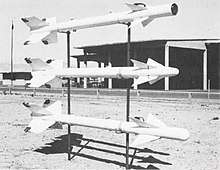

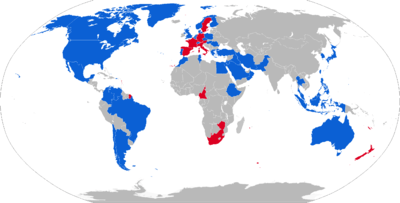

The Sidewinder is the most widely used air-to-air missile in the West, with more than 110,000 missiles produced for the U.S. and 27 other nations, of which perhaps one percent have been used in combat. It has been built under license by some other nations including Sweden, and can even equip helicopters, such as the Bell AH-1Z Viper. The AIM-9 is one of the oldest, least expensive, and most successful air-to-air missiles, with an estimated 270 aircraft kills in its history of use.[7] When firing a Sidewinder,[lower-roman 1] NATO pilots use the brevity code FOX-2.

The United States Navy hosted a 50th-anniversary celebration for the Sidewinder in 2002. Boeing won a contract in March 2010 to support Sidewinder operations through to 2055, guaranteeing that the weapons system will remain in operation until at least that date. Air Force Spokeswoman Stephanie Powell noted that due to its relatively low cost, versatility, and reliability it is "very possible that the Sidewinder will remain in Air Force inventories through the late 21st century".

Design

The AIM-9 is made up of a number of different components manufactured by different companies, including Aerojet and Raytheon. The missile is divided into four main sections: guidance, target detector, warhead, and rocket motor.

The guidance and control unit (GCU) contains most of the electronics and mechanics that enable the missile to function. At the very front is the IR seeker head utilizing the rotating reticle, mirror, and five CdS cells or "pan and scan" staring array (AIM-9X), electric motor, and armature, all protruding into a glass dome. Directly behind this are the electronics that gather data, interpret signals, and generate the control signals that steer the missile. An umbilical on the side of the GCU attaches to the launcher, which detaches from the missile at launch. To cool the seeker head, a 5,000 psi (34 MPa) argon bottle (TMU-72/B or A/B) is carried internally in Air Force AIM-9L/M variants, while the Navy uses a rail-mounted nitrogen bottle. The AIM-9X model contains a Stirling cryo-engine to cool the seeker elements. Two electric servos power the canards to steer the missile (except AIM-9X). At the back of the GCU is a gas grain generator or thermal battery (AIM-9X) to provide electrical power. The AIM-9X features high off-boresight capability; together with JHMCS (Joint Helmet-Mounted Cueing System), this missile is capable of locking on to a target that is in its field of regard said to be up to 90 degrees off boresight. The AIM-9X has several unique design features including built-in test to aid in maintenance and reliability, an electronic safe and arm device, an additional digital umbilical similar to the AMRAAM and jet vane control.

Next is a target detector with four IR emitters and detectors that detect whether the target is moving farther away. When it detects this action taking place, it sends a signal to the warhead safe and arm device to detonate the warhead. Versions older than the AIM-9L featured an influence fuze that relied on the target's magnetic field as input. Current trends in shielded wires and non-magnetic metals in aircraft construction rendered this obsolete.

The AIM-9H model contained a 25 lb (11 kg) expanding rod-blast fragmentary warhead. All other models up to the AIM-9M contained a 22 lb (10.0 kg) annular-blast fragmentary warhead. The missile's warhead rods can break rotor blades (an immediately fatal event for any helicopter).

Recent models of the AIM-9 are configured with an annular-blast fragmentation warhead, the WDU-17B by Argotech Corporation. The case is made from spirally wound spring steel filled with 8 lb (3.6 kg) of PBXN-3 explosive. The warhead features a safe/arm device requiring five seconds at 20 g (~200 m/s²) acceleration before the fuze is armed, giving a minimum range of approximately 2.5 km (1.6 mi).

The Mk36 solid-propellant rocket motor provides propulsion for the missile. A reduced-smoke propellant makes it difficult for a target to see and avoid the missile. This section also features the launch lugs used to hold the missile to the rail of the missile launcher. The forward of the three lugs has two contact buttons that electrically activate the motor igniter. The fins provide stability from an aerodynamic point of view, but it is the "rollerons" at the end of the wings providing gyroscopic precession to free-hinging control surfaces in the tail that prevent the missile from spinning in flight. The wings and fins of the AIM-9X are much smaller and control surfaces are reversed from earlier Sidewinders with the control section located in the rear, while the wings up front provide stability. The AIM-9X also features vectored thrust or jet vane control to increase maneuverability and accuracy, with four vanes inside the exhaust that move as the fins move. The last upgrade to the missile motor on the AIM-9X is the addition of a wire harness that allows communication between the guidance section and the control section, as well as a new 1760 bus to connect the guidance section with the launcher's digital umbilical.

The Sidewinder improved on the World War II-era Madrid IR range fuze used by Messerschmitt's Enzian experimental surface-to-air missile. The first innovation was to replace the "steering" mirror with a forward-facing mirror rotating around a shaft pointed out the front of the missile. The detector was mounted in front of the mirror. When the long axis of the mirror, the missile axis and the line of sight to the target all fell in the same plane, the reflected rays from the target reached the detector (provided the target was not very far off axis). Therefore, the angle of the mirror at the instant of detection (w1) estimated the direction of the target in the roll axis of the missile.

The yaw/pitch (angle w2) direction of the target depended on how far to the outer edge of the mirror the target was. If the target was further off axis, the rays reaching the detector would be reflected from the outer edge of the mirror. If the target was closer on axis, the rays would be reflected from closer to the centre of the mirror. Rotating on a fixed shaft, the mirror's linear speed was higher at the outer edge. Therefore, if a target was further off-axis, its "flash" in the detector occurred for a briefer time, or longer if it was closer to the center. The off-axis angle could then be estimated by the duration of the reflected pulse of infrared.

The Sidewinder also included a dramatically improved guidance algorithm. The Enzian attempted to fly directly at its target, feeding the direction of the telescope into the control system as it if were a joystick. This meant the missile always flew directly at its target, and under most conditions would end up behind it, "chasing" it down. This meant that the missile had to have enough of a speed advantage over its target that it did not run out of fuel during the interception.

The Sidewinder is not guided on the actual position recorded by the detector, but on the change in position since the last sighting. So if the target remained at 5 degrees left between two rotations of the mirror, the electronics would not output any signal to the control system. Consider a missile fired at right angles to its target; if the missile is flying at the same speed as the target, it should "lead" it by 45 degrees, flying to an impact point far in front of where the target was when it was fired. If the missile is traveling four times the speed of the target, it should follow an angle about 11 degrees in front. In either case, the missile should keep that angle all the way to interception, which means that the angle that the target makes against the detector is constant. It was this constant angle that the Sidewinder attempted to maintain. This "proportional pursuit" system is very easy to implement, yet it offers high-performance lead calculation almost for free and can respond to changes in the target's flight path,[8] which is much more efficient and makes the missile "lead" the target.

However, this system also requires the missile to have a fixed roll-axis orientation. If the missile spins at all, the timing based on the speed of rotation of the mirror is no longer accurate. Correcting for this spin would normally require some sort of sensor to tell which way is "down" and then adding controls to correct it. Instead, small control surfaces were placed at the rear of the missile with spinning disks on their outer surface; these are known as rollerons. Airflow over the disk spins them to a high speed. If the missile starts to roll, the gyroscopic force of the disk drives the control surface into the airflow, cancelling the motion. Thus the Sidewinder team replaced a potentially complex control system with a simple mechanical solution.

History

Origins

During World War II, various researchers in Germany designed infrared guidance systems of various complexity. The most mature development of these, codenamed Hamburg, was intended for use by the Blohm & Voss BV 143 glide bomb in the anti-shipping role. Hamburg used a single IR photocell as its detector along with a spinning disk with lines painted on it, alternately known as a "reticle" or "chopper". The reticle spun at a fixed speed, causing the output of the photocell to be interrupted in a pattern, and the details of this pattern indicated the bearing of the target. Although Hamburg and similar devices like Madrid were essentially complete, the work of mating them to a missile had not been carried out by the time the war ended.[9]

In the immediate post-war era, Allied military intelligence teams collected this information, along with many of the engineers working on these projects. Several lengthy reports on the various systems were produced and disseminated among the western aircraft firms, while a number of the engineers joined these companies to work on various missile projects. By the late 1940s a wide variety of missile projects were underway, from huge systems like the Bell Bomi to small systems like air-to-air missiles. By the early 1950s, both the US Air Force and Royal Air Force had started major IR seeker missile projects.[9]

The development of the Sidewinder missile began in 1946 at the Naval Ordnance Test Station (NOTS), Inyokern, California, now the Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake, California as an in-house research project conceived by William B. McLean. McLean initially called his effort "Local Fuze Project 602" using laboratory funding, volunteer help and fuze funding to develop what it called a heat-homing rocket. It did not receive official funding until 1951 when the effort was mature enough to show to Admiral William "Deak" Parsons, the Deputy Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd). It subsequently received designation as a program in 1952. The Sidewinder introduced several new technologies that made it simpler and much more reliable than its United States Air Force (USAF) counterpart, the AIM-4 Falcon, under development during the same period. After disappointing experiences with the Falcon in the Vietnam War, the Air Force replaced its Falcons with Sidewinders.

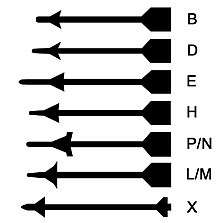

Nearly 100,000 of the first generation (AIM-9B/C/D/E) of the Sidewinder were produced with Raytheon and General Electric as major sub-contractors.[10] Philco-Ford produced the guidance and control sections of the early missiles.[10] The NATO version of the first generation missile was built under licence in Germany by Bodenseewerk Gerätetechnik; 9,200 examples were built.[10] A second generation of the missile (AIM-9G/H/J) was introduced during 1970. These were followed from the mid-seventies by the AIM-9L/P which was a substantial improvement on the early versions, particularly with an improved SR-116 reduced-smoke rocket motor.[10] The third generation of the missile (AIM-9L/M) are all-aspect missile which share little in common with the earlier missiles.[10]

The name Sidewinder was selected in 1950 and is the common name of Crotalus cerastes, a venomous rattlesnake, which uses infrared sensory organs to hunt warm-blooded prey.[10][11]

Originally called the Sidewinder 1, the first live firing was on 3 September 1952.[10] The missile intercepted a drone for the first time on the 11 September 1953.[10] The missile carried out 51 guided flights in 1954, and in 1955 production was authorised.[10]

In 1954, the US Air Force carried out trials with the original AIM-9A and the improved AIM-9B at the Holloman Air Development Center.[10] The first operational use of the missile was by Grumman F9F-8 Cougars and FJ-3 Furies of the United States Navy in the middle of 1956.[10] The Maximal effective range for AIM-9B is 2.6 NM or 4.8 Kilometers, maximal in flight speed is 1.7 Mach.

Combat debut: Taiwan Strait, 1958

The first combat use of the Sidewinder was on September 24, 1958, with the air force of the Republic of China (Taiwan), during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis. During that period of time, ROCAF North American F-86 Sabres were routinely engaged in air battles with the People's Republic of China over the Taiwan Strait. The PRC MiG-17s had higher altitude ceiling performance and in similar fashion to Korean War encounters between the F-86 and earlier MiG-15, the PRC formations cruised above the ROC Sabres, immune to their .50 cal weaponry and only choosing battle when conditions favored them. In a highly secret effort, the United States provided a few dozen Sidewinders to ROC forces and an Aviation Ordnance Team from the U.S. Marine Corps to modify their Sabres to carry the Sidewinder. In the first encounter on 24 September 1958, the Sidewinders were used to ambush the MiG-17s as they flew past the Sabres thinking they were invulnerable to attack. The MiGs broke formation and descended to the altitude of the Sabres in swirling dogfights. This action marked the first successful use of air-to-air missiles in combat, the downed MiGs being their first casualties.[12]

During the Taiwan Strait battles of 1958, a ROCAF AIM-9B hit a PLAAF MiG-17 without exploding; the missile lodged in the airframe of the MiG and allowed the pilot to bring both plane and missile back to base. Soviet engineers later said that the captured Sidewinder served as a "university course" in missile design and substantially improved Soviet air-to-air capabilities.[13] They were able to reverse-engineer a copy of the Sidewinder, which was manufactured as the Vympel K-13/R-3S missile, NATO reporting name AA-2 Atoll. There may have been a second source for the copied design: according to Ron Westrum in his book Sidewinder,[14] the Soviets obtained the plans for Sidewinder from a Swedish Air Force Colonel, Stig Wennerström. (According to Westrum, Soviet engineers copied the AIM-9 so closely that even the part numbers were duplicated, although this has not been confirmed from Soviet sources.)

The Vympel K-13 entered service with Soviet air forces in 1961.

Development during early 1960s

The Sidewinder subsequently evolved through a series of upgraded versions with newer, more sensitive seekers with various types of cooling and various propulsion, fuze, and warhead improvements. Although each of those versions had various seeker, cooling, and fusing differences, all but one shared infrared homing. The exception was the U.S. Navy AAM-N-7 Sidewinder IB (later AIM-9C), a Sidewinder with a semi-active radar homing seeker head developed for the F-8 Crusader. Only about 1,000 of these weapons were produced, many of which were later rebuilt as the AGM-122 Sidearm anti-radiation missile.

USAF adoption from 1964

The original USAF nomenclature for the Sidewinder was the GAR-8, although it too later adopted the name AIM-9. Although originally developed for the USN and a competitor to the USAF AIM-4 Falcon, the Sidewinder was subsequently introduced into USAF service. The US DoD directed that the F-4 Phantom be adopted by the USAF. The Air Force originally borrowed F-4B model Phantoms, which were equipped with AIM-9B Sidewinders as the short-range armament.

The first production USAF Phantoms were the F-4C model, which carried the AIM-9B Sidewinder, from December 1964. During the 1960s the USN and USAF pursued their own separate versions of the Sidewinder, but cost considerations later forced the development of common variants beginning with the AIM-9L.

Vietnam War service 1965–1973

When air combat started over North Vietnam in 1965, Sidewinder was the standard short range missile carried by the US Navy on its F-4 Phantom and F-8 Crusader fighters and could be carried on the A-4 Skyhawk and on the A-7 Corsair for self-defense. The US Air Force also used the Sidewinder on its F-4C Phantoms and when MiGs began challenging strike groups, the F-105 Thunderchief also carried the Sidewinder for self-defense. The USAF opted to carry only AIM-4 Falcon on their F-4D model Phantoms introduced to Vietnam service in 1967, but disappointment with combat use of the Falcon led to a crash effort to reconfigure the F-4D so that it could carry Sidewinders.

Performance of the 454 Sidewinders launched[15] during the war was not as satisfactory as hoped. Both the USN and USAF studied the performance of their aircrews, aircraft, weapons, training, and supporting infrastructure. The USAF conducted the classified Red Baron Report while the Navy conducted a study concentrating primarily on performance of air-to-air weapons that was informally known as the "Ault Report". The impact of both studies resulted in modifications to the Sidewinder by both services to improve its performance and reliability in the demanding air-to-air arena.

US Navy develops AIM-9D/G/H

The Navy Sidewinder design progression went from the early production B model to the D model that was used extensively in Vietnam. The G and H models followed with new forward canard design improving ACM performance and expanded acquisition modes and improved envelopes. The "Hotel" model followed shortly after the "Golf" and featured a solid state design that improved reliability in the carrier environment where shock from catapult launches and arrested landings had a deteriorating effect on the earlier vacuum tube designs. The Ault report had a strong impact on Sidewinder design, manufacture, and handling.

US Air Force develops AIM-9E/J/N/P

Once the Air Force adopted the Sidewinder as part of its arsenal, it developed the AIM-9E, introducing it in 1967. The "Echo" was an improved version of the basic AIM-9B featuring larger forward canards as well as a more aerodynamic IR seeker and an improved rocket motor. The missile, however still had to be fired at the rear quarter of the target, a drawback of all early IR missiles. Significant upgrades were applied to the first true dogfight version, the AIM-9J, which was rushed to the South-East Asia Theatre in July 1972 during the Linebacker campaign, in which many aerial encounters with North Vietnamese MiGs occurred. The Juliet model could be launched at up to 7.5g (74 m/s²) and introduced the first solid state components and improved actuators capable of delivering 90 lb⋅ft (120 N⋅m) torque to the canards, thereby improving dogfight prowess. In 1973, Ford began production of an enhanced AIM-9J-1, which was later redesignated the AIM-9N. The AIM-9J was widely exported. The J/N evolved into the P series, with five versions being produced (P1 to P5) including such improvements as new fuzes, reduced-smoke rocket motors, and all-aspect capability on the latest P4 and P5. BGT in Germany has developed a conversion kit for upgrading AIM-9J/N/P guidance and control assemblies to the AIM-9L standard, and this is being marketed as AIM-9JULI. The core of this upgrade is the fitting of the DSQ-29 seeker unit of the AIM-9L, replacing the original J/N/P seeker to give improved capabilities.

Summary of Vietnam War AIM-9 claimed aerial combat kills

| Missile firing aircraft | AIM-9 Sidewinder model (Type) | Aircraft downed | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-8E Crusader | AIM-9D | (1) MiG-21/(9) MiG-17s | US fighters launched from US aircraft carriers; USS Hancock, USS Oriskany, USS Bon Homme Richard, USS Ticonderoga |

| F-8C | AIM-9D | (3) MiG-17s/(1) MiG-21 | US fighters launched from USS Bon Homme Richard and USS Intrepid |

| F-8H | AIM-9D | (2) MiG-21s | US fighters launched from USS Bon Homme Richard |

| F-4B Phantom II | AIM-9D | (2) MiG-17s/(2) MiG-21s | US fighters launched from USS Constellation and USS Kitty Hawk |

| F-4J | AIM-9D | (2) MiG-21s | US fighters launched from USS America and USS Constellation |

| F-4B | AIM-9B | (1) MiG-17 | US fighters launched from USS Kitty Hawk |

| F-4B | AIM-9D | (7) MiG-17s/(2) MiG-19s | Fighters launched from USS Coral Sea and USS Midway |

| F-4J | AIM-9G | (7) MiG-17s/(7) MiG-21s | Fighters launched from USS Enterprise, USS America, USS Saratoga, USS Constellation, USS Kitty Hawk |

| Total MiG-17s | 29 | ||

| Total MiG-21s | 15 | ||

| Total MiG-19s | 2 | ||

| USN Total: | 46 |

| Missile firing aircraft | AIM-9 Sidewinder Model (Type) | Aircraft downed | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-4C | AIM-9B | (13) MiG-17s/(9) MiG-21s | USAF 45th Tactical Fighter Squadron (TFS), 389th TFS, 390th TFS, 433rd TFS, 480th TFS, 555th TFS |

| F-105D Thunderchief | AIM-9B | (3) MiG-17s | 333rd TFS, 469th TFS |

| F-4D | AIM-9E | (2) MiG-21s | 13th, 469th TFS |

| F-4E | AIM-9E | (4) MiG-21s | 13th TFS, 34th TFS, 35th TFS, 469th TFS |

| F-4D | AIM-9J | (2) MiG-19s/(1) MiG-21 | 523rd TFS, 555th TFS |

| Total MiG-17s | 16 | ||

| Total MiG-21s | 16 | ||

| Total MiG-19s | 2 | ||

| USAF Total: | 34 |

In total 452 Sidewinders were fired during the Vietnam War, resulting in a kill probability of 0.18.[17]

| Subtype | AIM-9B | AIM-9D | AIM-9E | AIM-9G | AIM-9H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service | Joint | USN | USAF | USN | USN |

| Seeker Design Features | |||||

| Origin | Naval Weapons Center | AIM-9B | AIM-9B | AIM-9D | AIM-9G |

| Detector | PbS | PbS | PbS | PbS | PbS |

| Cooling | Uncooled | Nitrogen | Peltier | Nitrogen | Nitrogen |

| Dome window | Glass | MgF2 | MgF2 | MgF2 | MgF2 |

| Reticle Speed (Hz) | 70 | 125 | 100 | 125 | 125 |

| Modulation | AM | AM | AM | AM | AM |

| Track Rate (°/s) | 11.0 | 12.0 | 16.5 | 12.0 | >12.0 |

| Electronics | thermionic | thermionic | hybrid | thermionic | solid state |

| Warhead | 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) blast-fragmentation |

11 kg (24 lb) Mk. 48 continuous rod |

4.5 kg (9.9 lb) blast-fragmentation |

11 kg (24 lb) Mk. 48 continuous rod |

11 kg (24 lb) Mk. 48 continuous rod |

| Fuze | Passive-IR | Passive-IR/HF | Passive-IR | Passive-IR/HF | Passive-IR/HF |

| Powerplant | |||||

| Manufacturer | Thiokol | Hercules | Thiokol | Hercules | Hercules/Bermite |

| Type | Mk.17 | Mk.36 | Mk.17 | Mk.36 | Mk.36 Mod 5, 6, 7 |

| Launcher | Aero-III | LAU-7A | Aero-III | LAU-7A | LAU-7A |

| Missile dimensions | |||||

| Length | 2.82 m (9.3 ft) | 2.86 m (9.4 ft) | 3 m (9.8 ft) | 2.86 m (9.4 ft) | 2.86 m (9.4 ft) |

| Span | 0.55 m (1.8 ft) | 0.62 m (2.0 ft) | 0.55 m (1.8 ft) | 0.62 m (2.0 ft) | 0.62 m (2.0 ft) |

| Weight | 70.39 kg (155.2 lb) | 88.5 kg (195 lb) | 74.5 kg (164 lb) | 87 kg (192 lb) | 84.5 kg (186 lb) |

Note: the speed of the B model was around 1.7 Mach and the other models above 2.5.

All-aspect variants

AIM-9C

As a Semi-Active Radar Homing (SARH) missile, the AIM-9C could be used from the frontal aspect of the target, provided a radar lock of sufficient quality was obtained.

AIM-9L

The next major advance in IR Sidewinder development was the AIM-9L ("Lima") model which was in full production in 1977.[18][19] This was the first "all-aspect" Sidewinder with the ability to attack from all directions, including head-on, which had a dramatic effect on close-in combat tactics. Its first combat use was by a pair of US Navy F-14s in the Gulf of Sidra in 1981 versus two Libyan Su-22 Fighters, both of the latter being destroyed by AIM-9Ls. Its first use in a large-scale conflict was by the United Kingdom during the 1982 Falklands War. In this campaign the "Lima" reportedly achieved kills from 80% of launches, a dramatic improvement over the 10–15% levels of earlier versions, scoring 17 kills and 2 shared kills against Argentine aircraft.[20]

In combat uses of the AIM-9L, opponents had not developed tactics for the evasion of head-on missile shots with it, making them more vulnerable. The AIM-9L was also the first Sidewinder that was a joint variant used by both the US Navy and Air Force since the AIM-9B. The "Lima" was distinguished from earlier Sidewinder variants by its double delta forward canard configuration and natural metal finish of the guidance and control section. The Lima was also built under license in Europe by a team headed by Diehl BGT Defence. There are a number of "Lima" variants in operational service at present. First developed was the 9L Tactical, which is an upgraded version of the basic 9L missile. Next was the 9L Genetic, which has increased infra-red counter-counter measures (IRCCM); this upgrade consisted of a removable module in the Guidance Control Section (GCS) which provided flare-rejection capability. Next came the 9L(I), which had its IRCCM module hardwired into the GCS, providing improved counter-countermeasures as well as an upgraded seeker system. Diehl BGT also markets the AIM-9L(I)-1 which again upgrades the 9L(I)GCS and is considered an operational equivalent to the initially "US only" AIM-9M.

AIM-9M

The subsequent AIM-9M ("Mike") has the all-aspect capability of the L model while providing all-around higher performance. The M model has improved capability against infrared countermeasures, enhanced background discrimination capability, and a reduced-smoke rocket motor. These modifications increase its ability to locate and lock-on to a target and decrease the chance of missile detection. Deliveries of the initial AIM-9M-1 began in 1982. The only changes from the AIM-9L to the AIM-9M were related to the Guidance Control Section (GCS). Several models were introduced in pairs with even numbers designating Navy versions and odd for USAF: AIM-9M-2/3, AIM-9M-4/5, and AIM-9M-6/7 which was rushed to the Persian Gulf area during Operation Desert Shield (1991) to address specific threats expected to be present.

The AIM-9M-8/9 incorporated replacement of five circuit cards and the related motherboard to update infrared counter-countermeasures (IRCCM) capability to improve 9M capability against the latest threat IRCM. The first AIM-9M-8/9 modifications, fielded in 1995, involved deskinning the guidance section and substitution of circuit cards at the depot level, which is labor-intensive and expensive—as well as removing missiles from inventory during the upgrade period. The AIM-9X concept is to use reprogrammable software to permit upgrades without disassembly.

AIM-9R

The Navy began development of AIM-9R, a Sidewinder seeker upgrade in 1987 that featured a focal-plane array (FPA) seeker using video-camera type charge-coupled device (CCD) detectors and featuring increased off-boresight capability. The technology at the time was restricted to visual (daylight) use only and the USAF did not agree on this requirement, preferring another technology path. AIM-9R reached flight test stage before it was cancelled and subsequently both services agreed to a joint development of the AIM-9X variant.

BOA/Boxoffice

China Lake developed an improved compressed carriage control configuration titled BOA. ("Compressed carriage" missiles have smaller control surfaces to allow more missiles to fit in a given space.[21] The surfaces may be permanently "clipped", or may fold out when the missile is launched.)

The BOA design reduced size of control surfaces, eliminating the rollerons, and returned to simple forward-canard design. Although the Navy and Air Force had jointly developed and procured AIM-9L/M, BOA was a Navy-only effort supported by internal China Lake Independent Research & Development (IR&D) funding. Meanwhile, the Air Force was pursuing a parallel effort to develop a compressed carriage version of Sidewinder, called Boxoffice, for the F-22. The Joint Chiefs of Staff directed that the services collaborate on AIM-9X, which ended these separate efforts. The results of BOA and Boxoffice were provided to the industry teams competing for AIM-9X, and elements of both can be found in the AIM-9X design.

AIM-9X

After looking at advanced short range missile designs during the AIM portion of the ACEVAL/AIMVAL Joint Test and Evaluation at Nellis AFB in the 1974–78 timeframe, the Air Force and Navy agreed on the need for the Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile AMRAAM. However, agreement over development of an Advanced Short Range Air-to-Air Missile ASRAAM was problematic and disagreement between the Air Force and Navy over design concepts (Air Force had developed AIM-82 and Navy had flight-tested Agile and flown it in AIMVAL). Congress eventually insisted the services work on a joint effort resulting in the AIM-9M, thereby compromising without exploring the improved off boresight and kinematic capability potential offered by Agile. In 1985, the Soviet Union did field a short range missile (SRM) (AA-11 Archer/R-73) that was very similar to Agile. At that point, the Soviet Union took the lead in SRM technology and correspondingly fielded improved infrared countermeasures (IRCM) to defeat or reduce the effectiveness of the latest Sidewinders. With the reunification of Germany and improved relations in the aftermath of the Soviet Union, the West became aware of how potent both the AA-11 and IRCM were and SRM requirements were readdressed.

For a brief period in the late 1980s, an ASRAAM effort led by a European consortium was in play under a Memorandum Of Agreement with the United States in which AMRAAM development would be led by the US and ASRAAM by the Europeans. The UK worked with the aft end of the ASRAAM and Germany developed the seeker (Germany had first-hand experience improving the Sidewinder seeker of the AIM-9J/AIM-9F). By 1990, technical and funding issues had stymied ASRAAM and the program appeared stalled, so in light of the threat of AA-11 and improved IRCM, the US embarked on determining requirements for AIM-9X as a counter to both the AA-11 and improved IRCM features. The first draft of the requirement was ready by 1991 and the primary competitors were Raytheon and Hughes. Later, the UK resolved to revive the ASRAAM development and selected Hughes to provide the seeker technology in the form of a high off-boresight capable Focal Plane Array. However, the UK did not choose to improve the turning kinematic capability of ASRAAM to compete with AA-11. As part of the AIM-9X program, the US conducted a foreign cooperative test of the ASRAAM seeker to evaluate its potential, and an advanced version featuring improved kinematics was proposed as part of the AIM-9X competition. In the end, the Hughes-evolved Sidewinder design, featuring virtually the same British funded seeker as used by ASRAAM, was selected as the winner.

The AIM-9X Sidewinder, developed by Raytheon engineers, entered service in November 2003 with the USAF (lead platform is the F-15C; the USN lead platform is the F/A-18C) and is a substantial upgrade to the Sidewinder family featuring an imaging infrared focal-plane array (FPA) seeker with claimed 90° off-boresight capability, compatibility with helmet-mounted displays such as the new U.S. Joint Helmet Mounted Cueing System, and a totally new three-dimensional thrust-vectoring control (TVC) system providing increased turn capability over traditional control surfaces. Utilizing the JHMCS, a pilot can point the AIM-9X missile's seeker and "lock on" by simply looking at a target, thereby increasing air combat effectiveness.[22] It retains the same rocket motor, fuze and warhead of the 9-"Mike", but its lower drag gives it improved range and speed.[23] AIM-9X also includes an internal cooling system, eliminating the need for use of launch-rail nitrogen bottles (U.S. Navy and Marines) or internal argon bottle (USAF). It also features an electronic safe and arm device similar to the AMRAAM, allowing reduction in minimum range and reprogrammable infrared Counter Counter Measures (IRCCM) capability that coupled with the FPA provide improved look down into clutter and performance against the latest IRCM. Though not part of the original requirement, AIM-9X demonstrated potential for a Lock-on After Launch capability, allowing for possible internal use for the F-35, F-22 Raptor and even in a submarine-launched configuration for use against ASW platforms.[24] The AIM-9X has been tested for a surface attack capability, with mixed results.[25]

Block II

Testing work on the AIM-9X Block II version began in September 2008.[26] The Block II adds Lock-on After Launch capability with a datalink, so the missile can be launched first and then directed to its target afterwards by an aircraft with the proper equipment for 360 degree engagements, such as the F-35 and F-22.[27] By January 2013, the AIM-9X Block II was about halfway through its operational testing and performing better than expected. NAVAIR reported that the missile was exceeding performance requirements in all areas, including lock-on after launch (LOAL). One area where the Block II needs improvement is helmetless high off-boresight (HHOBS) performance. It is functioning well on the missile, but performance is below that of the Block I AIM-9X. The HHOBS deficiency does not impact any other Block II capabilities, and is planned to be improved upon by a software clean-up build. Objectives of the operational test were due to be completed by the third quarter of 2013.[28] However, as of May 2014 there have been plans to resume operational testing and evaluation (including surface-to-air missile system compatibility).[29] As of June 2013, Raytheon has delivered 5,000 AIM-9X missiles to the armed services.[30]

In February 2015, the U.S. Army successfully launched an AIM-9X Block II Sidewinder from the new Multi-Mission Launcher (MML), a truck-mounted missile launch container that can hold 15 of the missiles. The MML is part of the Indirect Fire Protection Capability Increment 2-Intercept (IFPC Inc. 2-I) to protect ground forces against cruise missile and unmanned aerial vehicle threats. The X-model Block II Sidewinder has been determined by the Army to be the best solution to CM and UAV threats because of its passive IIR seeker. The MML will complement the AN/TWQ-1 Avenger air defense system and is expected to begin fielding in 2019.[31]

Block III

In September 2012, Raytheon was ordered to continue developing the Sidewinder into a Block III variant, even though the Block II had not yet entered service. The USN projected that the new missile would have a 60 percent longer range, modern components to replace old ones, and an insensitive munitions warhead, which is more stable and less likely to detonate by accident, making it safer for ground crews. The need for the AIM-9 to have an increased range was from digital radio frequency memory (DRFM) jammers that can blind the onboard radar of an AIM-120D AMRAAM, so the Sidewinder Block III's passive imaging infrared homing guidance system was a useful alternative. Although it could supplement the AMRAAM for beyond visual range (BVR) engagements, it would still be capable at performing within visual range (WVR). Modifying the AIM-9X was seen as a cost-effective alternative to developing a new missile in a time of declining budgets. To achieve the range increase, the rocket motor would have a combination of increased performance and missile power management. The Block III would "leverage" the Block II's guidance unit and electronics, including the AMRAAM-derived datalink. The Block III was scheduled to achieve initial operational capability (IOC) in 2022, following the increased number of F-35 Lightning II Joint Strike Fighters to enter service.[32][33] The Navy pressed for this upgrade in response to a projected threat which analysts have speculated will be due to the difficulty of targeting upcoming Chinese Fifth-generation jet fighters (Chengdu J-20, Shenyang J-31) with the radar guided AMRAAM,[34] specifically that Chinese advances in electronics will mean Chinese fighters will use their AESA radars as jammers to degrade the AIM-120's kill probability.[35] However, the Navy's FY 2016 budget cancelled the AIM-9X Block III as they cut down buys of the F-35C, as it was primarily intended to permit the fighter to carry six BVR missiles; the insensitive munition warhead will be retained for the AIM-9X program.[36]

| Subtype | AIM-9J | AIM-9L | AIM-9M | AIM-9P-4/5 | AIM-9R |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service | USAF | Joint | Joint | USAF | USN |

| Seeker design features | |||||

| Origin | AIM-9E | AIM-9H | AIM-9L | AIM-9J/N | AIM-9M |

| Detector | PbS | InSb | InSb | InSb | Focal-plane array |

| Cooling | Peltier | Argon | Argon | Argon | – |

| Dome window | MgF2 | MgF2 | MgF2 | MgF2 | Glass |

| Reticle speed (Hz) | 100 | 125 | 125 | 100 | Focal-plane array |

| Modulation | AM | FM | FM | FM | Focal-plane array |

| Track rate (°/s) | 16.5 | Classified | Classified | >16.5 | Classified |

| Electronics | Hybrid | Solid state | Solid state | Solid state | Solid state |

| Warhead | 4.5 kg (9.9 lb) blast-fragmentation |

9.4 kg (21 lb) WDU-17/B annular blast-fragmentation |

9.4 kg (21 lb) WDU-17/B annular blast-fragmentation |

Annular blast-fragmentation | Annular blast-fragmentation |

| Fuze | Passive-IR | IR/Laser | IR/Laser | IR/Laser | IR/Laser |

| Powerplant | |||||

| Manufacturer | Hercules/Aerojet | Hercules/Bermite | MTI/Hercules | Hercules/Aerojet | MTI/Hercules |

| Type | Mk.17 | Mk.36 Mod.7,8 | Mk.36 Mod.9 | SR.116 | Mk.36 Mod.9 |

| Launcher | Aero-III | Common | Common | Common | Common |

| Missile dimensions | |||||

| Length | 3 m (9.8 ft) | 2.89 m (9.5 ft) | 2.89 m (9.5 ft) | 3 m (9.8 ft) | 2.89 m (9.5 ft) |

| Span | 0.58 m (1.9 ft) | 0.64 m (2.1 ft) | 0.64 m (2.1 ft) | 0.58 m (1.9 ft) | 0.64 m (2.1 ft) |

| Weight | 77 kg (170 lb) | 86 kg (190 lb) | 86 kg (190 lb) | 86 kg (190 lb) | 86 kg (190 lb) |

Other Sidewinder developments

K-13 AA-2 Atoll

TC-1 Republic of China (Taiwan)

Chaparral/Sea Chaparral

A version for the U.S. Army with a launcher for four AIM-9D missiles mounted on a tracked vehicle and called the MIM-72/M48 Chaparral was also developed. In this configuration an operator sat in a protected capsule that was incorporated into the launcher assembly that rotated as an integrated unit. The Chaparral was introduced into service in 1969 and remained an integral part of the Army's air defense network until 1998.

Other ground launch platforms

In 2016 the AIM-9X was test fired from an Multi-Mission Launcher at the White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, USA.[37]

In May 2019 the AIM-9X Block II was test fired from the National Advanced Surface to Air Missile System (NASAMS) at the Andoya Test Center in Norway.[38]

AGM-122A Sidearm

The Sidewinder was also the basis for the AGM-122A Sidearm anti-radiation missile utilizing an AIM-9C guidance section modified to detect and track a radiating ground-based air defense system radar. The target-detecting device is modified for air-to-surface use, employing forward hemisphere acquisition capability. Sidearm stocks have apparently been expended, and the weapon is no longer in the active inventory.

Anti-tank variant

China Lake experimented with Sidewinders in the air-to-ground mode including use as an anti-tank weapon. Starting from 2008, the AIM-9X demonstrated its ability as a successful light air-to-ground missile.[39]

On 28 February 2018, the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps unveiled an anti-tank version of Sidewinder missile named "Azarakhsh missile". This project developed to use by attack helicopters and ground launchers.[40]

Larger rocket motor

Under the High Altitude Project, engineers at China Lake mated a Sidewinder warhead and seeker to a Sparrow rocket motor to experiment with usefulness of a larger motor.[41]

Operators

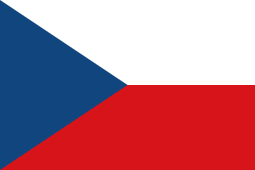

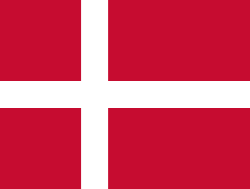

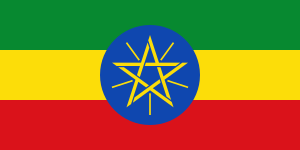

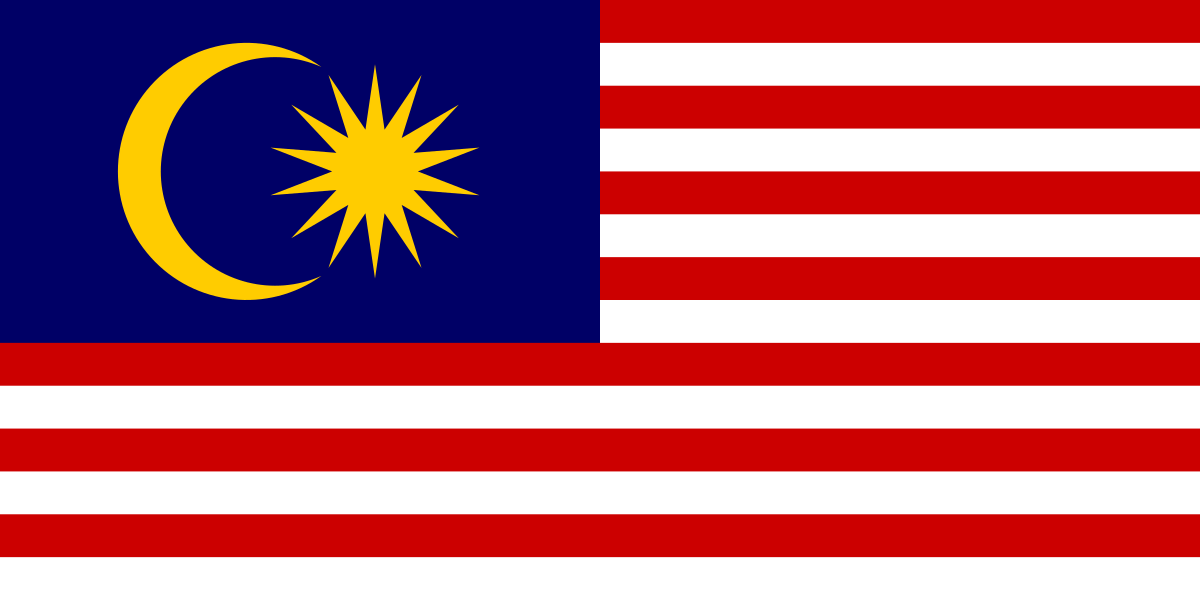

Current operators

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

Former operators

.svg.png)

Please note that this list is not exhaustive.

See also

Related development

- AGM-87 Focus

- Diamondback, a proposed enlarged, nuclear-armed version of Sidewinder

- K-13 (AA-2 Atoll)

- MIM-72 Chaparral

- AIM-95 Agile, Developed in the 1970s to (unsuccessfully) replace the AIM-9

- Sidewinder Arcas

Related lists

Comparable missiles

References

Notes

- Or other infrared-homing missile

Citations

- Sea Power (January 2006). Wittman, Amy; Atkinson, Peter; Burgess, Rick (eds.). "Air-to-Air Missiles". 49 (1). Arlington, Virginia: Navy League of the United States: 95–96. ISSN 0199-1337. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "GAO-15-342SP DEFENSE ACQUISITIONS Assessments of Selected Weapon Programs" (PDF). US Government Accountability Office. March 2015. p. 61. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/32277/here-is-what-each-of-the-pentagons-air-launched-missiles-and-bombs-actually-cost. Retrieved 15 Feb 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Babcock, Elizabeth (September 1999). Sidewinder Invention and Early Years. The China Lake Museum Foundation.

The Air Force subsequently procured Sidewinder AIM-9B missiles for its hottest tactical and strategic aircraft, p. 21

- Military Technology (August 2008). "News Flash". 32 (8). Heilsbachstraße 26 53123 Bonn-Germany: Mönch Publishing Group: 93–96. ISSN 0722-3226.

"Alliant Techsystems and RUAG Aerospace have signed a teaming agreement to provide full-service and upgrade support of the AIM-9P-3/4/5 Sidewinder family of IR-guided short-range air-to-air missiles.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: location (link) - "Air Weapons: Beyond Sidewinder". www.strategypage.com. Archived from the original on 3 February 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- "Raytheon AIM-9 Sidewinder". www.designation-systems.net. Archived from the original on 9 February 2010. Retrieved 2 February 2010.

- Echo-locating bats, as they pursue flying insects, also adopt such a strategy, see this PLoS Biology report: Ghose, K.; Horiuchi, T. K.; Krishnaprasad, P. S.; Moss, C. F. (18 April 2006). "Echo-locating Bats Use a Nearly Time-Optimal Strategy to Intercept Prey". PLoS Biology. 4 (5): e108. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040108. PMC 1436025. PMID 16605303.

- Kutzscher, Edgar (1957). "The Physical and Technical Development of Infrared Homing Devices". In Benecke, T; Quick, A (eds.). History of German Guided Missiles Development. NATO. Archived from the original on 2015-09-30. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- Tom Hildreth (March–April 1988). "The Sidewinder Missile". Air-Britain Digest. 40 (2): 39–40. ISSN 0950-7434.

- "U.S. Naval Museum of Armament & Technology". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Sidewinder AIM-9. US Naval Academy 2012. Archived from the original on 2 July 2018. Retrieved 21 November 2017.

- Secret City: A history of the Navy at China Lake. OCLC 851089182.

- Westrum, Ron (2013). Sidewinder: Creative Missile Development at China Lake. Annapolis, Maryland: U.S. Naval Institute. ISBN 978-1-59114-981-1.

- Michel III p. 287

- McCarthy Jr. p. 148-157

- Friedman, Norman (1989). The Naval Institute Guide to World Naval Weapon Systems. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-1-55750-262-9.

- Carlo, Kopp (1994-04-01). "The Sidewinder Story; The Evolution of the AIM-9 Missile". Australian Aviation. 1994 (April). Archived from the original on 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2007-01-04.

- Bonds 1989, p. 229.

- "F-16 Armament – AIM-9 Sidewinder". Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADP010957%5B%5D

- Doty, Steven R. (2008-02-29). "Kunsan pilots improve capability with AIM-9X missile". Air Force Link. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Sweetman, Bill, Warming trend, Aviation Week and Space Technology, July 8, 2013, p.26

- "Successful Test of an AIM-9X Missile by a Raytheon-Led Team Demonstrates Potential for Low Cost Solution in Littoral Joint Battlespace". 29 September 2007. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007.

- "Raytheon AIM-9X Block II Air/Air Missile." Archived 2011-09-26 at the Wayback Machine Defense Update, 20 September 2011.

- "Raytheon AIM-9X Block II Missile Completes First Captive Carry Flight". Raytheon. September 18, 2008. Retrieved November 2, 2018.

- "Raytheon AIM-9X Block II Missile Completes First Captive Carry Flight". Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- AIM-9X Block II performing better than expected Archived 2013-02-03 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, January 28, 2013

- David C. Isby (May 2014). "AIM-9X Block II resumes IOT&E". Jane's International Defence Review. 47: 16. ISSN 2048-3449.

- Raytheon Delivers 5,000th AIM-9X Sidewinder Air-to-Air Missile Archived 2014-03-07 at the Wayback Machine – Deagel.com, 15 June 2013

- New Launcher to Deploy C-RAM, C-UAV and Counter Cruise-Missile Defenses by 2019 Archived 2015-07-09 at the Wayback Machine – Defense-Update.com, 28 March 2015

- "US Navy hopes to increase AIM-9X range by 60%." Archived 2013-07-21 at the Wayback Machine – Flightglobal.com, 18 July 2013

- New Sidewinder Tweaks Archived 2012-09-07 at the Wayback Machine – Strategypage.com, September 5, 2012

- Sweetman, Bill (June 19, 2013). "Raytheon Looks At Options For Long-Range AIM-9". Aviation Week. Archived from the original on February 21, 2014. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- Sweetman, Bill, Warming Trend, Aviation Week and Space Technology, July 8, 2013, p.26

- F-35Cs Cut Back As U.S. Navy Invests In Standoff Weapons Archived 2015-02-05 at the Wayback Machine – Aviationweek.com, 3 February 2015

- Collins, Boyd. "U.S. Army successfully fires AIM-9X missile from new interceptor launch platform". www.army.mil. United States Army. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- Reichmann, Kelsey. "Norway's Air Force tests Sidewinder missile". defensenews.com. Defense News. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "AIM-9X Sidewinder demonstrates Air-To-Surface capability". Archived from the original on 28 September 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "PressTV-Iran's IRGC unveils new anti-armor missile". Archived from the original on 2018-03-04. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- "1970 China Lake Photo Gallery". www.chinalakealumni.org. Archived from the original on 2018-06-10. Retrieved 2018-02-22.

- La Franchi, Peter (27 March 2007). "Australia confirms AIM-9X selection for Super Hornets". Flight International. Archived from the original on 7 September 2008. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- Jennings, Gareth. "Norway and Taiwan join AIM-9X Block II user-community | IHS Jane's 360". IHS Jane's 360. London. Archived from the original on 2016-07-05. Retrieved 2016-07-04.

- "International Market Research – Defense Trade Guide Update 2003". 13 October 2007. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- "Finland Ordering 150 AIM-9X Sidewinders". Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- "Taking On Iran's Air Force – Defense Tech". 2006-05-17. Archived from the original on 12 June 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "PH completes inspection of Raytheon for FA-50's air-to-air missiles – Update Philippines". 18 July 2017. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- "150 AIM-9 Sidewinder Missiles for Saudi Arabia". Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- "SIPRI arms transfer database". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. 19 March 2012. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017. Retrieved 27 April 2012.

- "Turkey Buys 127 AIM-9X Sidewinder Missiles". Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- "AIM-9B Sidewinder". South African Air Force Association. Archived from the original on 27 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

Bibliography

- Bonds, Ray ed. The Modern US War Machine. New York City: Crown Publishers, 1989. ISBN 0-517-68802-6.

- Bonds, Ray and David Miller (2002). "AIM-9 Sidewinder". Illustrated Directory of Modern American Weapons. Zenith Imprint. ISBN 978-0-7603-1346-6.

- Clancy, Tom (1996). "Ordnance: How Bombs Got 'Smart'". Fighter Wing. London: HarperCollins, 1995. ISBN 978-0-00-255527-2.

- Doty, Steven R. (2008-02-29). "Kunsan pilots improve capability with AIM-9X missile". Air Force Link. Archived from the original on 2 March 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- Babcock, Elizabeth (1999). Sidewinder – Invention and Early Years. The China Lake Museum Foundation. 26 pp. A concise record of the development of the original Sidewinder version and the central people involved in its design.

- McCarthy, Donald J. Jr. MiG Killers, A Chronology of U.S. Air Victories in Vietnam 1965–1973. 2009, Specialty Press, North Branch, MN, U.S.A. ISBN 978-1-58007-136-9

- Michel III, Marshall L. Clashes, Air Combat Over North Vietnam 1965–1972. 1997. ISBN 978-1-59114-519-6.

- Westrum, Ron (1999). "Sidewinder—Creative missile development at China Lake." Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-951-2

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to AIM-9 Sidewinder. |

- Defense Industry Daily – AIM-9X Block II: The New Sidewinder Missile

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- AIM-9 Sidewinder on GlobalSecurity.org

- Raytheon AAM-N-7/GAR-8/AIM-9 Sidewinder – Designation Systems

- The Sidewinder Story

- Sidewinder at Howstuffworks.com

- NAMMO Raufoss – Nordic Ammunition Company

- F-15As launching AIM-9 Sidewinders at QF-4 on YouTube

- Rolleron demonstration on YouTube

- "Fox Two!" From Aviation History magazine, March 2013. Includes photos & video