District 9

District 9 is a 2009 science fiction action film directed by Neill Blomkamp, written by Blomkamp and Terri Tatchell, and produced by Peter Jackson and Carolynne Cunningham. It is a co-production of New Zealand, the United States and South Africa. The film stars Sharlto Copley, Jason Cope, and David James, and was adapted from Blomkamp's 2006 short film Alive in Joburg.

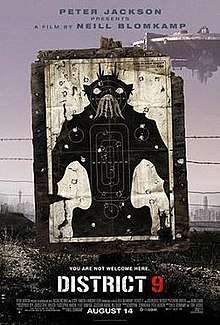

| District 9 | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Neill Blomkamp |

| Produced by | |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Alive in Joburg[lower-alpha 1] by Neill Blomkamp |

| Starring |

|

| Music by | Clinton Shorter[1][2] |

| Cinematography | Trent Opaloch |

| Edited by | Julian Clarke |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Sony Pictures Releasing |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes[3] |

| Country | |

| Language | English |

| Budget | US$30 million[5] |

| Box office | US$210.8 million[5] |

The film is partially presented in a found footage format by featuring fictional interviews, news footage, and video from surveillance cameras. The story, which explores themes of humanity, xenophobia and social segregation, begins in an alternate 1982, when an alien spaceship appears over Johannesburg, South Africa. When a population of sick and malnourished insectoid aliens are discovered on the ship, the South African government confines them to an internment camp called District 9. Twenty years later, during the government's relocation of the aliens to another camp, one of the confined aliens named Christopher Johnson, who is about to try to escape from Earth with his son and return home, crosses paths with a bureaucrat leading the relocation named Wikus van der Merwe. The title and premise of District 9 were inspired by events in Cape Town's District Six, during the apartheid era.

A viral marketing campaign for the film began in 2008 at San Diego Comic-Con, while the theatrical trailer debuted in July 2009. District 9 was released by TriStar Pictures on 14 August 2009, in North America and became a financial success, earning over $210 million at the box office. It also received acclaim from critics, who praised the film's direction, performances, themes, and story, with some calling it one of the best science fiction films of the 2000s, and garnered numerous awards and nominations, including four Academy Award nominations for Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Visual Effects, and Best Film Editing.[6]

Plot

In 1982, a giant extraterrestrial spaceship arrives and hovers over the South African city of Johannesburg. An investigation team finds over a million malnourished aliens (derogatorily called "Prawns") inside, and the South African government relocates them to a camp called District 9. However, over the years it turns into a slum, and locals often complain that the aliens are filthy, ignorant lawbreakers who bleed resources from humans.

Following unrest between the aliens and locals, the government hires Multinational United (MNU), a huge weapons manufacturer, to relocate the aliens to a new camp outside the city. Piet Smit, an MNU executive, appoints MNU employee and his son-in-law Wikus van de Merwe, to lead the relocation. Meanwhile, three aliens, Christopher Johnson, his young son CJ and his friend Paul, search a District 9 garbage dump for alien fuel in Prawn technology, which Christopher has had them spend the last twenty years synthesizing enough of to enact his plan. They finally finish in Paul's shack as the relocation begins but when Wikus comes to the shack to serve Paul a notice, he finds the hidden container with the fuel and accidentally sprays some of it in his face while confiscating it. Paul is killed by Koobus Venter, a cruel MNU mercenary.

Wikus begins mutating into a Prawn, starting with his left arm injured after the fuel exposure. He is immediately taken to the brutal MNU lab, where researchers discover his chimeric DNA grants him the ability to operate Prawn weaponry, that is biologically restricted for them. Wanting to capture this human/alien hybridity before Wikus fully transforms, Smit orders Wikus's body to be vivisected and harvested for its profitable properties. Wikus, however, overpowers the lab personnel and escapes. While Venter's forces hunt for him, a smear story is broadcast, one that reaches Wikus' wife and Smit's daughter Tania, claiming Wikus is a wanted fugitive who has contracted a contagious disease from copulating with aliens.

Wikus takes refuge in District 9, finding Christopher and the spaceship's concealed command module dropship underneath his house. Christopher explains to Wikus the confiscated fuel is crucial to his plan of reactivating the dropship, and if he can get them in the dropship to the mothership he can cure Wikus. Wikus attempts to acquire weapons from the District 9 Nigerian arms dealer Obesandjo, who wants to eat Wikus's alien arm to gain alien abilities. Wikus, however, seizes an alien weapon and escapes.

Wikus and Christopher force their way through MNU to the lab and retrieve the fuel. However, after seeing the barbarous experiments MNU has performed on his people in the lab (including a dissected Paul), Christopher tells Wikus he must return home as fast as possible for help and cannot undo Wikus’ mutation until he returns in three years due to the limited supply of the fuel. Enraged, Wikus knocks Christopher down and attempts to fly the module to the mothership himself, but it is shot down by Venter's forces. Venter captures Wikus and Christopher, but Obesandjo's gang ambushes the MNU convoy and seizes Wikus.

Meanwhile, CJ, remaining hidden in the dropship, remotely activates the mothership and a large, alien, mechanized battle suit in Obesandjo's base. The suit guns down the Nigerians, and Wikus enters the suit and rescues Christopher from the mercenaries. Heading to the dropship, the two come under heavy fire, and Wikus stays behind to fend off the mercenaries, buying time for Christopher, who promises to return after three years and heal Wikus, to leave. After all of the other mercenaries are killed, Venter finally cripples the suit and is about to execute Wikus when slum aliens attack and dismember him alive. Christopher makes it into the dropship with CJ, and the dropship is levitated via a tractor beam back into the mothership, which leaves Earth.

MNU's experiments are exposed, and the aliens are moved to the new camp, named District 10. Tania finds a metal flower on her doorstep, giving her hope that Wikus is still alive. Wikus, now completely alien, is shown in a junkyard crafting the flower for his wife.

Cast

- Sharlto Copley as Wikus van de Merwe, a mild-mannered, bumbling, awkward bureaucrat at the MNU Department of Alien Affairs, who becomes infected with an alien fluid, slowly turning him into one of the "prawns". This was the first time acting professionally in a feature film for Copley, a friend of director Blomkamp.[7]

- Jason Cope as Christopher Johnson, a District 9 prawn who assists Wikus in fighting MNU. Cope also performed the role of Grey Bradnam, the UKNR Chief Correspondent and all the speaking aliens, as well as for the cameraman Trent[8]

- David James as Colonel Koobus Venter, an aggressive, sadistic, and xenophobic PMC mercenary-soldier sent to capture Wikus. He is shown as taking pleasure in killing the aliens and responding brutally to anyone who opposes him

- Vanessa Haywood as Tania Smit-van de Merwe, Wikus's wife

- Mandla Gaduka as Fundiswa Mhlanga, Wikus's assistant and trainee during the eviction

- Eugene Wanangwa Khumbanyiwa as Obesandjo, a paralyzed psychopathic Nigerian gang leader who believes that eating alien body parts will enable him to operate their weapons

- Louis Minnaar as Piet Smit, director of MNU, and Wikus's father-in-law

- Kenneth Nkosi as Thomas, an MNU security guard

- William Allen Young as Dirk Michaels, CEO of MNU

- Robert Hobbs as Ross Pienaar

- Nathalie Boltt as Sarah Livingstone, a sociologist at Kempton Park University

- Sylvaine Strike as Katrina McKenzie, a doctor from the Department of Social Assistance

- John Sumner as Les Feldman, a MIL engineer

- Nick Blake as Francois Moraneu, a member of the CIV Engineer Team

- Jed Brophy as James Hope, the ACU chief of police

- Vittorio Leonardi as Michael Bloemstein, from the MNU Department of Alien Civil Affairs

- Johan van Schoor as Nicolaas van de Merwe, Wikus's father

- Marian Hooman as Sandra van de Merwe, Wikus's mother

- Jonathan Taylor as the Doctor

- Stella Steenkamp as Phyllis Sinderson, a co-worker of Wikus's

- Tim Gordon as Clive Henderson, an entomologist at WLG University

- Nick Boraine as Lieutenant Weldon, Colonel Venter's right-hand man

- Trevor Coppola as MNU Mercenary

- Morne Erasmus as MNU Medic

Themes

Like Alive in Joburg, the short film on which the feature film is based, the setting of District 9 is inspired by historical events during the apartheid era, particularly alluding to District Six, an inner-city residential area in Cape Town, declared a "whites only" area by the government in 1966, with 60,000 people forcibly removed to Cape Flats, 25 km (16 miles) away.[9] The film also refers to contemporary evictions and forced removals to suburban ghettos in post-apartheid South Africa, as well as the resistance of its residents.[10][11] This includes the high-profile attempted forced removal of the Joe Slovo informal settlement in Cape Town to temporary relocation areas in Delft, plus evictions in the shack settlement, Chiawelo, where the film was actually shot.[8] Blikkiesdorp, a temporary relocation area in Cape Town, has also been compared with the District 9 camp earning a front-page spread in the Daily Voice.[12][13]

The film emphasizes the irony of Wikus and the impact of his experiences on his personality, which show him becoming more humane as he becomes less biologically human.[14] Chris Mikesell from the University of Hawaii newspaper Ka Leo writes that "Substitute 'black,' 'Asian,' 'Mexican,' 'illegal,' 'Jew,’ 'white,’ or any number of different labels for the word 'prawn' in this film and you will hear the hidden truth behind the dialogue".[15]

Themes of racism and xenophobia are shown in the form of speciesism. Used to describe the aliens, the word "prawn" is a reference to the Parktown prawn, a king cricket species considered a pest in South Africa.[16][17] Copley has said that the theme is not intended to be the main focus of the work, but can work at a subconscious level even if it is not noticed.[18]

Duane Dudek of the Journal Sentinel wrote that "The result is an action film about xenophobia, in which all races of humans are united in their dislike and mistrust of an insect-like species".[19]

Another underlying theme in District 9 is states' reliance on multinational corporations (whose accountability is unclear and whose interests are not necessarily congruent with democratic principles) as a form of government-funded enforcement. As MNU represents the type of corporation which partners with governments, the negative portrayal of MNU in the film depicts the dangers of outsourcing militaries and bureaucracies to private contractors.[20][21]

Production

Development

Producer Peter Jackson planned to produce a film adaptation based on the Halo video-game franchise with first-time director Neill Blomkamp. Due to a lack of financing, the Halo adaptation was placed on hold. Jackson and Blomkamp discussed pursuing alternative projects and eventually chose to produce and direct, respectively, District 9 featuring props and items originally made for the Halo movie.[22] Blomkamp had previously directed commercials and short films, but District 9 was his first feature film. The director co-wrote the script with his wife, Terri Tatchell, and chose to film in South Africa, where he was born.[23][24]

In District 9, Tatchell and Blomkamp returned to the world explored in his short film Alive in Joburg, choosing characters, moments and concepts that they found interesting including the documentary-style filmmaking, staged interviews, alien designs, alien technology/mecha suits, and the parallels to racial conflict and segregation in South Africa, and fleshing out these elements for the feature film.[25]

QED International financed the negative cost. After the 2007 American Film Market, QED partnered with Sony's TriStar Pictures for distribution in several territories.[26][27]

Filming

The film was shot on location in Chiawelo, Soweto during a time of violent unrest in Alexandra (Gauteng) and other South African townships involving clashes between native South Africans and Africans born in other countries.[28] The location that portrays District 9 is itself a real impoverished neighbourhood from which people were being forcibly relocated to government-subsidised housing.[8] Several scenes were shot at the Ponte building.[29]

Filming for District 9 took place during the winter in Johannesburg. According to director Neill Blomkamp, during the winter season, Johannesburg "actually looks like Chernobyl", a "nuclear apocalyptic wasteland". Blomkamp wanted to capture the deserted, bleak atmosphere and environment, so he and the crew had to film during the months of June through July. The film took a total of 60 days of shooting. Filming in December raised another issue in that there was much more rain. Due to the rain, there was a lot of greenery to work with, which Blomkamp did not want. Blomkamp had to cut some of the vegetation in the scenery to portray the setting as desolate and dark.

The film features many weapons and vehicles produced by the South African arms industry, including the R5 and Vektor CR-21 assault rifles, Denel NTW-20 20 mm anti-materiel rifle, BXP submachine gun, Casspir armoured personnel carrier, Ratel infantry fighting vehicle, Rooikat armoured fighting vehicle, Atlas Oryx helicopter and militarized Toyota Hilux "technical" pickup truck.[30][31]

Blomkamp said no single film influenced District 9, but cited the 1980s "hardcore sci-fi/action" films such as Alien, Aliens, The Terminator, Terminator 2: Judgment Day, Predator and RoboCop as subconscious influences. The director said, "I don't know whether the film has that feeling or not for the audience, but I wanted it to have that harsh 1980s kind of vibe—I didn't want it to feel glossy and slick."[25]

Because of the amount of hand-held shooting required for the film, the producers and crew decided to shoot using the digital Red One 4K camera. Cinematographer Trent Opaloch used nine digital Red Ones owned by Peter Jackson for primary filming.[32] According to HD Magazine, District 9 was shot on RED One cameras using build 15, Cooke S4 primes and Angenieux zooms. The documentary-style and CCTV-style cam footage was shot on the Sony EX1/EX3 XDCAM-HD. Additionally, the post-production team was warned that the most RED Camera footage they could handle a day was about an hour and a half. When that got to five hours a day additional resources were brought in, and 120 terabytes of data was filled.[33]

Visual effects

Already as a young child living in South Africa, Blomkamp was captivated by artwork and visual effects. "I knew I wanted to be in movies ... So I thought I wanted to be in special effects, like model-making and prosthetic effects." The combination of knowing he would find a career in the visual effects area and the advancement of technology allowing better computer graphics capabilities led him to work at a Canadian post-production company as a visual effects artist. The aliens in District 9 were designed by Weta Workshop, and the design was executed by Image Engine.

Blomkamp wanted the aliens to maintain both humane and barbaric features in the design of the creatures. According to Terri Tatchell, the director's writing partner, "They are not appealing, they are not cute, and they don't tug at our heartstrings. He went for a scary, hard, warrior-looking alien, which is much more of a challenge." The look of the alien, with its exoskeleton-crustacean hybrid and crab-like shells, was meant to initially evoke a sense of disgust from viewers but as the story progresses, the audience was meant to sympathize with these creatures who had such human-like emotions and characteristics. Blomkamp established criteria for the design of the aliens. He wanted the species to be insect-like but also bipedal. The director wanted the audience to relate to the aliens and said of the restriction on the creature design, "Unfortunately, they had to be human-esque because our psychology doesn't allow us to really empathize with something unless it has a face and an anthropomorphic shape. Like if you see something that's four-legged, you think it's a dog; that's just how we're wired ... If you make a film about an alien force, which is the oppressor or aggressor, and you don't want to empathize with them, you can go to town. So creatively that's what I wanted to do but story-wise, I just couldn't."[34]

Blomkamp originally sought to have Weta Digital design the creatures, but the company was busy with effects for Avatar. The director then decided to choose a Vancouver-based effects company because he anticipated making films there in the future and because British Columbia offered a tax credit. Blomkamp met with Image Engine and considered them "a bit of a gamble" since the company had not pursued a project as large as a feature film.[25] Aside from the aliens appearing on the operating table in the medical lab, all of them were created using CGI visual effects.[35]

Weta Digital designed the 2½-kilometre-diameter mothership[36] and the drop ship, while the exo-suit and the little pets were designed by The Embassy Visual Effects. Zoic Studios performed overflow 2D work.[25] On-set live special effects were created by MXFX.[37]

Music

The music for District 9 was scored by Canadian composer Clinton Shorter, who spent three weeks preparing for the film. Director Neill Blomkamp wanted a "raw and dark" score, but one that maintained its South African roots. This was a challenge for Shorter, who found much of the South African music he worked with to be optimistic and joyful. Unable to get the African drums to sound dark and heavy, Shorter used a combination of taiko drums and synthesized instruments for the desired effects, with the core African elements of the score conveyed in the vocals and smaller percussion.[38] Both the score and soundtrack feature music and vocals from Kwaito artists.

Marketing

Sony Pictures launched a "Humans Only" marketing campaign to promote District 9. Sony's marketing team designed its promotional material to emulate the segregational billboards that appear throughout the film.[34] Billboards, banners, posters, and stickers were thus designed with the theme in mind, and the material was spread across public places such as bus stops in various cities, including "humans only" signs in certain locations and providing toll-free numbers to report "non-human" activity.[39][40] This marketing strategy was designed to provoke reactions in its target audience, namely: sci-fi fans, and people concerned with social justice. Hence the overtly obvious use of fake segregational propaganda.[41] According to Dwight Caines, Sony's president of digital marketing, an estimated 33,000 phone calls were made to the toll-free numbers during a two-week period with 2,500 of them leaving voicemails with reports of alien sightings.[42] Promotional material was also presented at the 2008 San Diego Comic-Con, advertising the website D-9.com,[43] which had an application presented by the fictional Multi-National United (MNU). The website had a local alert system for Johannesburg (the film's setting), news feeds, behavior recommendations, and rules and regulations. Other viral websites for the film were also launched, including an MNU website with a countdown timer for the film's release,[44] an anti-MNU blog run by fictional alien character Christopher Johnson,[45] and an MNU-sponsored educational website.[46][47] An online game for District 9 has also been made where players can choose to be a human or an alien. Humans are MNU agents on patrol trying to arrest or kill aliens. Aliens try to avoid capture from MNU agents whilst searching for alien canisters.[48] This digital approach to marketing follows a rising trend among digital natives who develop marketing trends and techniques which are appropriate to the digital age, and is cost-efficient due to its reliance on social media and communications. This breaking down, and circumvention of existing marketing structures follows postmodernist theory in cinema.[49][50]

WETA released in July 2010 Christopher Johnson and Son as sculptures.[51]

According to the American Humane Association, the film displays an unauthorized "no animals were harmed" end credit, which is a registered trademark of the group.[52]

Reception

Box office

District 9 grossed US$115.6 million from the United States and Canada, with a worldwide total of $210,819,611, against a production budget of US$30 million.[5] Documents from the Sony Pictures hack revealed the film turned a profit of $67 million.[53]

It opened in 3,048 theatres in Canada and the United States on 14 August 2009, and the film ranked first at the weekend box office with an opening gross of US$37.4 million. Among comparable science fiction films in the past, its opening attendance was slightly less than the 2008 film Cloverfield and the 1997 film Starship Troopers. The audience demographic for District 9 was 64 percent male and 57 percent people 25 years or older.[39] The film stood out as a summer film that generated strong business despite little-known casting.[54] Its opening success was attributed to the studio's unusual marketing campaign. In the film's second weekend, it dropped 49% in revenue while competing against the opening film Inglourious Basterds for the male audience, as Sony Pictures attributed the "good hold" to District 9's strong playability.[55]

The film enjoyed similar success in the UK with an opening gross of £2,288,378 showing at 447 cinemas.[56] It was just as popular in South Africa, where it was filmed on location.

Critical response

Rotten Tomatoes reported that 90% of critics gave the film a positive review, based on a sample of 311 reviews, with an average score of 7.8/10. The website's consensus states, "Technically brilliant and emotionally wrenching, District 9 has action, imagination, and all the elements of a thoroughly entertaining science-fiction classic."[57] At Metacritic, which assigns a weighted average rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film has received a score of 81 based on 36 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[58]

Sara Vilkomerson of The New York Observer wrote, "District 9 is the most exciting science fiction movie to come along in ages; definitely the most thrilling film of the summer; and quite possibly the best film I've seen all year."[59] Christy Lemire from the Associated Press was impressed by the plot and thematic content, claiming that "District 9 has the aesthetic trappings of science fiction but it's really more of a character drama, an examination of how a man responds when he's forced to confront his identity during extraordinary circumstances."[60] Entertainment Weekly's Lisa Schwarzbaum described it as "... madly original, cheekily political, [and] altogether exciting ..."[61]

Roger Ebert praised the film for "giving us aliens to remind us not everyone who comes in a spaceship need to be angelic, octopod or stainless steel", but complained that "the third act is disappointing, involving standard shoot-out action. No attempt is made to resolve the situation, and if that's a happy ending, I've seen happier. Despite its creativity, the film remains space opera and avoids the higher realms of science-fiction."[62] Josh Tyler of Cinema Blend says the film is unique in interpretation and execution, but considers it to be a knockoff of the 1988 film Alien Nation.[63]

IGN listed District 9 at #24 on a list of the Top 25 Sci-Fi Films of All Time.[64]

Political response

Nigeria's Information Minister Dora Akunyili asked movie theatres around the country to either ban the film or edit out specific references to the country, because of the film's negative depiction of the Nigerian characters as criminals and cannibals. Letters of complaint were sent to the producer and distributor of the film demanding an apology. She also said the gang leader Obesandjo is almost identical in spelling and pronunciation to the surname of former president Olusegun Obasanjo.[65] The film was later banned in Nigeria; the Nigerian Film and Video Censors Board was asked to prevent cinemas from showing the film and also to confiscate it.[66]

Hakeem Kae-Kazim, a Nigerian-born British actor, also criticized the portrayal of Nigerians in the film,[67] telling the Beeld (an Afrikaans-language daily newspaper): "Africa is a beautiful place and the problems it does have can not be shown by such a small group of people."

However, the Malawian actor Eugene Khumbanyiwa, who played Obesandjo, has stated that the Nigerians in the cast of District 9 were not perturbed by the portrayal of Nigerians in the film, and that the film should not be taken literally: "It's a story, you know. It's not like Nigerians do eat aliens. Aliens don't even exist in the first place."[68]

Teju Cole, a Nigerian-American writer, has commented that the "one-dimensionality of the Nigerian characters is striking," even when taking into account that District 9 is meant to be a fable. He suggests two possible explanations for Blomkamp's narrative choice: first, that it is meant to reflect anti-foreigner sentiment within South Africa, or second, that it simply represents an oversight on Blomkamp's part.[69]

In 2013, the movie was one of several discussed by David Sirota in Salon.com in an article concerning white savior narratives in film.[70]

Alexandra Heller Nicholas discusses Wikus's self-identity in District 9 as problematic due to him being a white man and the hero of the film. Nicholas argues that a white savior "disempowers the film’s allegory to apartheid that comments on the corruption of the South African government" as well as the discrimination black South Africans dealt with during and post-apartheid. Making Wikus the "white savior" backtracks from the main message of District 9 which is to show the audience the detrimental effects "of colonialism brought by the Western world". Another point Nicholas makes is that District 9 is a "stereotypical White Savior film". She states that the plot is about a white man working for the government, who has roots "in South Africa's apartheid culture", involuntarily joins the "victims of apartheid". In this case, instead of black people, it's prawns.[71]

Doctor Shohini Chauduri wrote that District 9 even echoes apartheid in its title, as it is reminiscent "of District 6 in Cape Town, declared a whites-only area under the Group Areas Act ..." She also discusses how the wide shots used in District 9 strongly emphasize the idea of exclusion under apartheid. The separation of people and "prawns" into human and non-human zones mark South Africa's social divisions.[72]

Accolades

District 9 was named one of the top 10 independent films of 2009 by the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures. The film received four Academy Awards nominations for: Best Motion Picture of the Year (Peter Jackson, Carolynne Cunningham), Best Writing, Adapted Screenplay (Neill Blomkamp, Terri Tatchell), Best Achievement in Film Editing (Julian Clarke), Best Achievement in Visual Effects (Dan Kaufman, Peter Muyzers, Robert Habros, Matt Aitken); seven British Academy Film Awards nominations: Best Cinematography (Trent Opaloch), Best Screenplay – Adapted (Neill Blomkamp, Terri Tatchell), Best Editing (Julian Clarke), Best Production Design (Philip Ivey, Guy Potgieter), Best Sound (Brent Burge, Chris Ward, Dave Whitehead, Michael Hedges, Ken Saville), Best Special Visual Effects (Dan Kaufman, Peter Muyzers, Robert Habros, Matt Aitken), Best Director (Neill Blomkamp); five Broadcast Film Critics Association nominations: Best Makeup (Won), Best Screenplay, Adapted (Neill Blomkamp, Terri Tatchell), Best Sound, Best Visual Effects, Best Action Movie; and one Golden Globe nomination: Best Screenplay – Motion Picture (Neill Blomkamp, Terri Tatchell).

It is the fifth TriStar Pictures film ever nominated for Best Picture at the Academy Awards (the previous four were As Good as It Gets, Jerry Maguire, Bugsy and Places in the Heart). It won the 2009 Bradbury Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America.[73]

Home media

The Blu-ray Disc and region 1 code widescreen edition of District 9 as well as the 2-disc special-edition version on DVD was released on 22 December 2009. The DVD and Blu-ray Disc includes the documentary "The Alien Agenda: A Filmmaker's Log" and the special features "Metamorphosis: The Transformation of Wikus", "Innovation: Acting and Improvisation", "Conception and Design: Creating the World of District 9", and "Alien Generation: Visual Effects".[74] The demo for the video game God of War III featured in the 2009 Electronic Entertainment Expo is also included with the Blu-ray release of District 9 playable on the Sony PlayStation 3.[75][76] District 9 will be released on 4K Blu-Ray on October 13 2020.[77]

Future

On 1 August 2009, two weeks before District 9 was released to cinemas, Neill Blomkamp hinted that he intended to make a sequel if the film was successful enough. During an interview on the Rude Awakening 94.7 Highveld Stereo breakfast radio show, he alluded to it, saying "There probably will be." Nevertheless, he revealed that his next project is unrelated to the District 9 universe.[78] In an interview with Rotten Tomatoes, Blomkamp stated that he was "totally" hoping for a follow-up: "I haven't thought of a story yet but if people want to see another one, I'd love to do it."[79] Blomkamp has posed the possibility of the next movie in the series being a prequel.[80] In an interview with Empire magazine posted on 28 April 2010, Sharlto Copley suggested that a follow-up, while very likely, would be about two years away, given his and Neill Blomkamp's current commitments.[81]

In an interview with IGN in June 2013, Blomkamp said, "I really want to make a District 9 sequel. I genuinely do. The problem is I have a bunch of ideas and stuff that I want to make. I'm relatively new to this—I'm about to make my third film, and now the pattern that I'm starting to realise is very true is that you lock yourself into a film beyond the film you're currently working on. But it just doesn't work for me." Referring to a potential sequel, Blomkamp said "[he] want[s] to make District 10 at some point".[82] As of June 2020, there's no update on the sequel of whether it is in development or cancelled.

Notes

- Despite the film being based on the short film, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences recognizing the film as an adaptation of said short, the film itself never mentions being based on it.

References

- "The Expanse: Interview: Composer Clinton Shorter". SciFi Bulletin, interview by Paul Simpson

- "CD Review: District 9". Film Music Magazine. By Daniel Schweiger • 14 September 2009

- "District 9". British Board of Film Classification. 21 July 2009. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "District 9 (2009)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 July 2014.

- "District 9 (2009)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 16 July 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2015.

- "The 82nd Annual Oscar Nominations". The New York Times. 2 February 2010. Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- Swietek, Frank (7 August 2009). "Neill Blomkamp and Sharlto Copley on "District 9"". Interviews. One Guy's Opinion. Archived from the original on 14 September 2009. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- "5 Things You Didn't Know About District 9". IO9. 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- Corliss, Richard (13 August 2009). "'District 9' Review: The Summer's Coolest Fantasy Film". Time. Archived from the original on 16 August 2009. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- "The real 'District 9' – South Africa's shack dwellers". Guardian Weekly. 28 August 2009. Archived from the original on 18 November 2007.

- de Waal, Shaun (28 August 2009). "Loving the Aliens". Film. Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009.

- Blikkiesdoprp housingdisaster has become Cape Flats' own...District 9 in The Daily Voice, South Africa, 3 October 2009

- "UN affiliated NGO asks the City to reconsider Symphony Way's eviction to Blikkiesdorp which will be decided in Court on Wednesday". Anti-Eviction Campaign. 5 October 2009. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009.

- Kaye, Don. "If Geeks Ran the Oscars". MSN Movies. Archived from the original on 24 December 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2010.

- Mikesell, Chris (26 August 2009). "District 9 reveals human inhumanity". Ka Leo. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- "Interview with Neill Blomkamp on the Highveld Stereo 94.7 radio station". 19 August 2009. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009.

- Sermon, Sarah (30 September 2013). Close Encounters of the Invasive Kind: Imperial History in Selected British Novels of Alien-encounter Science Fiction After World War II (1st ed.). Germany: LIT Verlag. p. 66. ISBN 978-3643903914.

- "Xenophobia, Racism Drive Alien Relocation in District 9". Wired. 12 August 2009. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Dudek, Duane (13 August 2009). "'District 9' social theme isn't so alien – JSOnline". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- "Hold the Prawns". SACSIS. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- "District 9, Ugly Marvel". SACSIS. Archived from the original on 22 September 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- Haske, Steve (30 May 2017). "The Complete, Untold History of Halo". Waypoint. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- Fleming, Michael (1 November 2007). "Peter Jackson gears up for 'District'". Variety. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- Leotta, A. (2015). Peter Jackson. The Bloomsbury Companions to Contemporary Filmmakers. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 126–29. ISBN 978-1-62356-096-6. Retrieved 16 February 2018.

- Desowitz, Bill (14 August 2009). "Neill Blomkamp Talks District 9". VFXWorld. AWN, Inc. Archived from the original on 20 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Frater, Patrick (4 November 2007). "Sony to release Jackson's 'District'". Variety. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Lee Jr, John J; Gillen, Anne Marie (3 November 2010). The Producer's Business Handbook: The Roadmap for the Balanced Film Producer. New York: Focal Press. p. 56. ISBN 0240814630.

- Itzkoff, Dave (5 August 2009). "A Young Director Brings a Spaceship and a Metaphor in for a Landing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Blair, Ian (10 March 2015). "I, Robot". Werner Publishing Corp. p. 4. Archived from the original on 13 July 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- Rule, Andrew. "District 9 is one long sales pitch for South Africa's arms industry". The Week with First Post. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014.

- "District 9, Movie, 2009". Internet Movie Cars Database. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013.

- Caranicas, Peter (14 August 2009). "'District' lenser braces for invasion". International. Variety. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- Attack Of The Terabytes Archived 9 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Oldham, Stuart (14 August 2009). "Interview: Neill Blomkamp". Variety. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Alfio, Leotta (17 December 2015). Peter Jackson. New York, USA: Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 128. ISBN 9781623569488. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- Cinefex Archived 29 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine 119, page 31

- MXFX Physical Special Effects Archived 1 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Hoover, Tom (2009). "Interviews: Clinton Shorter – The Music of District 9". Score Notes. Archived from the original on 9 September 2009. Retrieved 8 September 2009.

- Gray, Brandon (16 August 2009). "Weekend Report: Humans Welcome District 9". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on 18 August 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2009.

- Billington, Alex (14 August 2009). "For Humans Only: A Look Back at District 9's Success Story". FirstShowing.net. First Showing, LLC. Archived from the original on 19 August 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- Kerrigan, Finola (2017). Film Marketing. Routledge. ISBN 1-317-74704-6.

- Lee, Chris (19 June 2009). "Alien' Bus-Stop Ads Create A Stir". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 31 October 2016.

- "D-9.com". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 25 July 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- "Multi-National United". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- "MNU Spreads Lies". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 8 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- "Maths from Outer Space: An MNU Sponsored Initiative". Sony Pictures. Archived from the original on 7 September 2009. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- Billington, Alex (30 July 2008). "Next Big Viral: Neill Blomkamp's District 9 – For Humans Only". FirstShowing.net. First Showing, LLC. Archived from the original on 3 September 2009. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- "New District 9 Online Game, Trailer Coming!". comingsoon.net. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- "Film Marketing">Kerrigan, Finola (2017). Film Marketing. Routledge. ISBN 1-317-74704-6.

- Hill, ed. by John; Willemen, Pamela Church Gibson ; consultant ed. Richard Dyer, E. Ann Kaplan, Paul (1998). The Oxford Guide to Film Studies (Repr. [d. Ausg.] 1998. ed.). New York: Oxford university press. pp. 96–105. ISBN 0-19-871124-7.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Debi Moore (10 July 2010). "Weta's First District 9 Figure Revealed: Christopher Johnson and Son". Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Unauthorized End Credits Archived 15 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Physical Year End 2011-Budget Presentation". WikiLeaks. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- McClintock, Pamela (16 August 2009). "'District 9' invades top of box office". Variety. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- McClintock, Pamela (23 August 2009). "Tarantino's 'Basterds' storms box office". Variety. Archived from the original on 30 August 2009. Retrieved 30 August 2009.

- Fletcher, Alex (9 September 2009). "'District 9' claims UK box office No.1". digitalspy.com. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- "District 9 (2009)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "District 9". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 21 August 2009. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- Sara Vilkomerson. "District 9 Blew My Mind!". Observer. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Christy Lemire. "Review: Dramatic twists in store in 'District 9'". The San Francisco Chronicle. Archived from the original on 17 August 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Lisa Schwarzbaum. "Movie Review: District 9". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Roger Ebert (12 August 2009). "Throw another prawn on the barbie". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 15 August 2009. Retrieved 12 August 2009.

- Too Close To Call: 10 Ways District 9 Is An Alien Nation Knockoff Archived 28 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine, review by Josh Tyler, Cinema Blend, 10 August 2009

- "District 9". IGN. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- "Nigerian officials: "District 9" not welcome here". The San Diego Union-Tribune. Associated Press. 19 September 2009. Retrieved 19 February 2018.

- "Govt bans showing of District 9 film in Nigeria". Vanguard. 25 September 2009. Archived from the original on 1 October 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- Smith, David (2 September 2009). "District 9 labelled xenophobic by Nigerians". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- "BBC News | Africa | Nigeria 'offended' by sci-fi film". 19 September 2009. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- "COMMENT: DISTRICT 9 AND THE NIGERIANS | Africa is a Country". 11 September 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- Sirota, David (21 February 2013). "Oscar loves a white savior". Salon.com. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- Emilye Denny (2017). "There is no need for a White Savior". Challening Borders.

- Dr. Shohini Chaudhuri, Cinema of the Dark Side. 2014 (Uninvited Visitors pp.135-143)

- Standlee, Kevin (15 May 2010). "Nebula Awards Results". Science Fiction Awards Watch. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "District 9 Blu-ray and DVD Art Hovers Over Us". DreadCentral. Archived from the original on 5 April 2011.

- Caiazzo, Anthony (28 October 2009). "District 9 Forged Together With God of War III". Sony Computer Entertainment. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- Barton, Steve (30 October 2009). "District 9 Blu-ray to Include God of War III Demo". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 30 October 2009.

- "District 9 - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved 27 July 2020.

- "District 9 director already thinking about a sequel". SCI FI Wire. 31 July 2009. Archived from the original on 19 September 2009. Retrieved 29 August 2009.

- Mueller, Matt. "Neill Blomkamp Talks District 9 — RT Interview" Archived 6 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Rotten Tomatoes, 3 September 2009.

- "Will The Next District 9 Be A Prequel?". Empire Online. 10 January 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2010.

- "Sharlto Copley On The District 9 Sequel". Empire Online. 28 April 2010. Archived from the original on 17 May 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Neill Blomkamp Talks About A District 9 Sequel And Star Wars Archived 16 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine