Jacques Offenbach

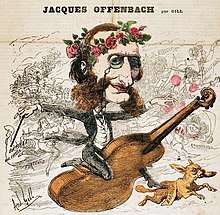

Jacques Offenbach (/ˈɒfənbɑːx/, also US: /ˈɔːf-/, French: [ʒak ɔfɛnbak], German: [ˈʔɔfn̩bax] (![]()

Born in Cologne, the son of a synagogue cantor, Offenbach showed early musical talent. At the age of 14, he was accepted as a student at the Paris Conservatoire but found academic study unfulfilling and left after a year. From 1835 to 1855 he earned his living as a cellist, achieving international fame, and as a conductor. His ambition, however, was to compose comic pieces for the musical theatre. Finding the management of Paris' Opéra-Comique company uninterested in staging his works, in 1855 he leased a small theatre in the Champs-Élysées. There he presented a series of his own small-scale pieces, many of which became popular.

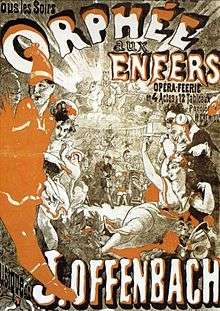

In 1858, Offenbach produced his first full-length operetta, Orphée aux enfers ("Orpheus in the Underworld"), which was exceptionally well received and has remained one of his most played works. During the 1860s, he produced at least 18 full-length operettas, as well as more one-act pieces. His works from this period included La belle Hélène (1864), La Vie parisienne (1866), La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867) and La Périchole (1868). The risqué humour (often about sexual intrigue) and mostly gentle satiric barbs in these pieces, together with Offenbach's facility for melody, made them internationally known, and translated versions were successful in Vienna, London and elsewhere in Europe.

Offenbach became associated with the Second French Empire of Napoleon III; the emperor and his court were genially satirised in many of Offenbach's operettas. Napoleon III personally granted him French citizenship and the Légion d'Honneur. With the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, Offenbach found himself out of favour in Paris because of his imperial connections and his German birth. He remained successful in Vienna and London, however. He re-established himself in Paris during the 1870s, with revivals of some of his earlier favourites and a series of new works, and undertook a popular U.S. tour. In his last years he strove to finish The Tales of Hoffmann, but died before the premiere of the opera, which has entered the standard repertory in versions completed or edited by other musicians.

Life and career

Early years

Offenbach was born Jacob or Jakob Offenbach[n 1] to a Jewish family, in the German city of Cologne, which was then a part of Prussia.[11][n 2] His birthplace in the Großer Griechenmarkt was a short distance from the square that is now named after him, the Offenbachplatz.[4] He was the second son and the seventh of ten children of Isaac Juda Offenbach né Eberst (1779–1850) and his wife Marianne, née Rindskopf (c. 1783–1840).[12] Isaac, who came from a musical family, had abandoned his original trade as a bookbinder and earned an itinerant living as a cantor in synagogues and playing the violin in cafés.[13] He was generally known as "der Offenbacher", after his native town, Offenbach am Main, and in 1808 he officially adopted Offenbach as a surname.[n 3] In 1816 he settled in Cologne, where he became established as a teacher, giving lessons in singing, violin, flute and guitar, and composing both religious and secular music.[8]

When Jacob was six years old, his father taught him to play the violin; within two years the boy was composing songs and dances, and at the age of nine he took up the cello.[8] As he was by then the permanent cantor of the local synagogue, Isaac could afford to pay for his son to take lessons from the well-known cellist Bernhard Breuer. Three years later, the biographer Gabriel Grovlez records, the boy was giving performances of his own compositions, "the technical difficulties of which terrified his master", Breuer.[15] Together with his brother Julius (violin) and sister Isabella (piano), Jacob played in a trio at local dance halls, inns and cafés, performing popular dance music and operatic arrangements.[16][n 4] In 1833, Isaac decided that the two most musically talented of his children, Julius (then aged 18) and Jacob (14) needed to leave the provincial musical scene of Cologne to study in Paris. With generous support from local music lovers and the municipal orchestra, with whom they gave a farewell concert on 9 October, the two young musicians, accompanied by their father, made the four-day journey to Paris in November 1833.[17]

Isaac had been given letters of introduction to the director of the Paris Conservatoire, Luigi Cherubini, but he needed all his eloquence to persuade Cherubini even to give Jacob an audition. The boy's age and nationality were both obstacles to admission.[n 5] Cherubini had several years earlier refused the 12-year-old Franz Liszt admission on similar grounds,[19] but he eventually agreed to hear the young Offenbach play. He listened to his playing and stopped him, saying, "Enough, young man, you are now a pupil of this Conservatoire."[20] Julius was also admitted. Both brothers adopted French forms of their names, Julius becoming Jules and Jacob becoming Jacques.[21]

Isaac hoped to secure permanent employment in Paris but failed to do so and returned to Cologne.[20] Before leaving, he found a number of pupils for Jules; the modest earnings from those lessons, supplemented by fees earned by both brothers as members of synagogue choirs, supported them during their studies. At the conservatoire, Jules was a diligent student; he graduated and became a successful violin teacher and conductor, and led his younger brother's orchestra for several years.[22] By contrast, Jacques was bored by academic study and left after a year. The conservatoire's roll of students notes against his name "Struck off on the 2 December 1834 (left of his own free will)".[n 6]

Cello virtuoso

Having left the conservatoire, Offenbach was free from the stern academicism of Cherubini's curriculum, but as the biographer James Harding writes, "he was free, also, to starve."[25] He secured a few temporary jobs in theatre orchestras before gaining a permanent appointment in 1835 as a cellist at the Opéra-Comique. He was no more serious there than he had been at the conservatoire, and regularly had his pay docked for playing pranks during performances; on one occasion, he and the principal cellist played alternate notes of the printed score, and on another they sabotaged some of their colleagues' music stands to make them collapse in mid-performance.[1] Nevertheless, his earnings from his orchestral work enabled him to take lessons with the celebrated cellist Louis-Pierre Norblin.[26] He made a favourable impression on the composer and conductor Fromental Halévy, who gave him lessons in composition and orchestration and wrote to Isaac Offenbach in Cologne that the young man was going to be a great composer.[27] Some of Offenbach's early compositions were programmed by the fashionable conductor Louis Antoine Jullien.[28] Offenbach and another young composer Friedrich von Flotow collaborated on a series of works for cello and piano.[29] Although Offenbach's ambition was to compose for the stage, he could not gain an entrée to Parisian theatre at this point in his career; with Flotow's help, he built a reputation composing for and playing in the fashionable salons of Paris.[30]

Among the salons at which Offenbach most frequently appeared was that of the comtesse de Vaux. There he met Hérminie d'Alcain (1827–1887), the daughter of a Carlist general.[31] They fell in love, but he was not yet in a financial position to propose marriage.[32] To extend his fame and earning power beyond Paris, he undertook tours of France and Germany. Among those with whom he performed were Anton Rubinstein and, in a concert in Offenbach's native Cologne, Liszt.[4] In 1844, probably through English family connections of Hérminie,[33] he embarked on a tour of England. There, he was immediately engaged to appear with some of the most famous musicians of the day, including Mendelssohn, Joseph Joachim, Michael Costa and Julius Benedict.[32] The Era wrote of his debut performance in London, "His execution and taste excited both wonder and pleasure, the genius he exhibited amounting to absolute inspiration."[34] The British press reported a triumphant royal command performance; The Illustrated London News wrote, "Herr Jacques Offenbach, the astonishing Violoncellist, performed on Thursday evening at Windsor before the Emperor of Russia, the King of Saxony, Queen Victoria, and Prince Albert with great success."[35][n 7] The use of "Herr" rather than "Monsieur", reflecting the fact that Offenbach remained a Prussian citizen, was common to all the British press coverage of Offenbach's 1844 tour.[37] The ambiguity of his nationality sometimes caused him difficulty in later life.[38]

Offenbach returned to Paris with his reputation and his bank balance both much enhanced. The last remaining obstacle to his marriage to Hérminie was the difference in their professed religions; he converted to Roman Catholicism, with the comtesse de Vaux acting as his sponsor. Isaac Offenbach's views on his son's conversion from Judaism are unknown.[39] The wedding took place on 14 August 1844; the bride was 17 years old, and the bridegroom was 25.[39] The marriage was lifelong, and happy, despite some extramarital dalliances on Offenbach's part.[40][n 8] After Offenbach's death, a friend said that Hérminie "gave him courage, shared his ordeals and comforted him always with tenderness and devotion".[42]

Returning to the familiar Paris salons, Offenbach quietly shifted the emphasis of his work from being a cellist who also composed to being a composer who played the cello.[43] He had already published many compositions, and some of them had sold well, but now he began to write, perform and produce musical burlesques as part of his salon presentations.[44] He amused the comtesse de Vaux's 200 guests with a parody of Félicien David's currently fashionable Le désert, and in April 1846 gave a concert at which seven operatic items of his own composition were premiered before an audience that included leading music critics.[44] After some encouragement and some temporary setbacks, he seemed on the verge of breaking into theatrical composition when Paris was convulsed by the 1848 revolution, which swept Louis Philippe from the throne and led to serious bloodshed in the streets of the capital.[45] Offenbach hastily took Hérminie and their recently born daughter to join his family in Cologne. He thought it politic to revert temporarily to the name Jacob.[46]

Returning to Paris in February 1849, Offenbach found the grand salons closed down. He went back to working as a cellist, and occasional conductor, at the Opéra-Comique, but was not encouraged in his aspirations to compose.[47] His talents had been noted by the director of the Comédie Française, Arsène Houssaye, who appointed him musical director of the theatre, with a brief to enlarge and improve the orchestra.[48] Offenbach composed songs and incidental music for eleven classical and modern dramas for the Comédie Française in the early 1850s. Some of his songs became very popular, and he gained valuable experience in writing for the theatre. Houssaye later wrote that Offenbach had done wonders for his theatre.[49] The management of the Opéra-Comique, however, remained uninterested in commissioning him to compose for its stage.[50] The composer Debussy later wrote that the musical establishment could not cope with Offenbach's irony, which exposed the "false, overblown quality" of the operas they favoured – "the great art at which one was not allowed to smile".[51]

Bouffes-Parisiens, Champs-Élysées

Between 1853 and 1855, Offenbach wrote three one-act operettas and managed to have them staged in Paris.[n 9] They were all well received, but the authorities of the Opéra-Comique remained unmoved. Offenbach found more encouragement from the composer, singer and impresario Florimond Ronger, known professionally as Hervé. At his theatre, the Folies-Nouvelles, which had opened the previous year, Hervé pioneered French light comic opera, or "opérette".[15][52] In The Musical Quarterly, Martial Teneo and Theodore Baker wrote, "Without the example set by Hervé, Offenbach might perhaps never have become the musician who penned Orphée aux Enfers, La belle Hélène, and so many other triumphant works."[53] Offenbach approached Hervé, who agreed to present a new one-act operetta with words by Jules Moinaux and music by Offenbach, called Oyayaye ou La reine des îles.[n 10] It was presented on 26 June 1855 and was well received. Offenbach's biographer Peter Gammond describes it as "a charming piece of nonsense".[57] The piece depicts a double-bass player, played by Hervé, shipwrecked on a cannibal island, who after several perilous encounters with the female chief of the cannibals makes his escape using his double-bass as a boat.[54] Offenbach pressed ahead with plans to present his works himself at his own theatre[57] and to abandon further thoughts of acceptance by the Opéra-Comique.[n 11]

Offenbach had chosen his theatre, the Salle Lacaze in the Champs-Élysées.[60] The location and the timing were ideal for him. Paris was about to be filled between May and November with visitors from France and abroad for the 1855 Great Exhibition. The Salle Lacaze was next to the exhibition site. He later wrote:

In the Champs-Élysées, there was a little theatre to let, built for [the magician] Lacaze but closed for many years. I knew that the Exhibition of 1855 would bring many people into this locality. By May, I had found twenty supporters and on 15 June I secured the lease. Twenty days later, I gathered my librettists and I opened the "Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens".[61]

The description of the theatre as "little" was accurate: it could only hold an audience of at most 300.[n 12] It was therefore well suited to the tiny casts permitted under the prevailing licensing laws: Offenbach was limited to three speaking (or singing) characters in any piece.[n 13] With such small forces, full-length works were out of the question, and Offenbach, like Hervé, presented evenings of several one-act pieces.[64] The opening of the theatre was a frantic rush, with less than a month between the issue of the licence and the opening night on 5 July 1855.[65] During this period Offenbach had to "equip the theatre, recruit actors, orchestra and staff, find authors to write material for the opening programme – and compose the music."[64] Among those he recruited at short notice was Ludovic Halévy, the nephew of Offenbach's early mentor Fromental Halévy. Ludovic was a respectable civil servant with a passion for the theatre and a gift for dialogue and verse. While maintaining his civil service career he went on to collaborate (sometimes under discreet pseudonyms) with Offenbach in 21 works over the next 24 years.[4]

Halévy wrote the libretto for one of the pieces in the opening programme, but the most popular work of the evening had words by Moinaux. Les deux aveugles, "The Two Blind Men" is a comedy about two beggars feigning blindness. During rehearsals there had been some concern that the public might judge it to be in poor taste,[66] but it was not only the hit of the season in Paris: it was soon playing successfully in Vienna, London and elsewhere.[67] Another success that summer was Le violoneux, which made a star of Hortense Schneider in her first role for Offenbach. Aged 22, when she auditioned for him, she was engaged on the spot. From 1855 she was a key member of his companies through much of his career.[67]

The Champs-Élysées in 1855 were not yet the grand avenue laid out by Baron Haussmann in the 1860s, but an unpaved allée.[65] The public who were flocking to Offenbach's theatre in the summer and autumn of 1855 could not be expected to venture there in the depths of a Parisian winter. He cast about for a suitable venue and found the Théâtre des Jeunes Élèves, known also as the Salle Choiseul or Théâtre Comte,[15] in central Paris. He entered into partnership with its proprietor and moved the Bouffes-Parisiens there for the winter season. The company returned to the Salle Lacaze for the 1856, 1857, and 1859 summer seasons, performing at the Salle Choiseul in the winter.[68] Legislation enacted in March 1861 prevented the company from using both theatres, and appearances at the Salle Lacaze were discontinued.[69]

Salle Choiseul

Offenbach's first piece for the company's new home was Ba-ta-clan (December 1855), a well-received piece of mock-oriental frivolity, to a libretto by Halévy.[70] He followed it with 15 more one-act operettas over the next three years.[4] They were all for the small casts permitted under his licence, although at the Salle Choiseul he was granted an increase from three to four singers.[65]

Under Offenbach's management, the Bouffes-Parisiens staged works by many composers. These included new pieces by Leon Gastinel and Léo Delibes. When Offenbach asked Rossini's permission to revive his comedy Il signor Bruschino, Rossini replied that he was pleased to be able to do anything for "the Mozart of the Champs-Élysées".[n 14] Offenbach revered Mozart above all other composers. He had an ambition to present Mozart's neglected one-act comic opera Der Schauspieldirektor at the Bouffes-Parisiens, and he acquired the score from Vienna.[65] With a text translated and adapted by Léon Battu and Ludovic Halévy, he presented it during the Mozart centenary celebrations in May 1856 as L'impresario; it was popular with the public[79] and also greatly enhanced the critical and social standing of the Bouffes-Parisiens.[80] By command of the emperor, Napoleon III, the company performed at the Tuileries palace shortly after the first performance of the Mozart piece.[65]

In a long article in Le Figaro in July 1856, Offenbach traced the history of comic opera. He declared that the first work worthy to be called opéra-comique was Philidor's 1759 Blaise le savetier, and he described the gradual divergence of Italian and French notions of comic opera, with verve, imagination and gaiety from Italian composers, and cleverness, common sense, good taste and wit from the French composers.[n 15] He concluded that comic opera had become too grand and inflated. His disquisition was a preliminary to the announcement of an open competition for aspiring composers.[82] A jury of French composers and playwrights including Daniel Auber, Fromental Halévy, Ambroise Thomas, Charles Gounod and Eugène Scribe considered 78 entries; the five short-listed entrants were all asked to set a libretto, Le docteur miracle, written by Ludovic Halévy and Léon Battu.[83] The joint winners were Georges Bizet and Charles Lecocq. Bizet became, and remained, a devoted friend of Offenbach. Lecocq and Offenbach took a dislike to one another, and their subsequent rivalry was not altogether friendly.[82][84]

Although the Bouffes-Parisiens played to full houses, the theatre was constantly on the verge of running out of money, principally because of what his biographer Alexander Faris calls "Offenbach's incorrigible extravagance as a manager".[80] An earlier biographer, André Martinet, wrote, "Jacques spent money without counting. Whole lengths of velvet were swallowed up in the auditorium; costumes devoured width after width of satin."[n 16] Moreover, Offenbach was personally generous and liberally hospitable.[85] To boost the company's finances, a London season was organised in 1857, with half the company remaining in Paris to play at the Salle Choiseul and the other half performing at the St James's Theatre in the West End of London.[65] The visit was a success, but did not cause the sensation that Offenbach's later works did in London.[86]

Orphée aux enfers

In 1858, the government lifted the licensing restrictions on the number of performers, and Offenbach was able to present more ambitious works. His first full-length operetta, Orphée aux enfers ("Orpheus in the Underworld"), was presented in October 1858. Offenbach, as usual, spent freely on the production, with scenery by Gustave Doré, lavish costumes, a cast of twenty principals, and a large chorus and orchestra.[87]

As the company was particularly short of money following an abortive season in Berlin, a big success was urgently needed. At first the production seemed merely to be a modest success. It soon benefited from an outraged review by Jules Janin, the critic of the Journal des Débats; he condemned the piece for profanity and irreverence (ostensibly to Roman mythology but in reality to Napoleon and his government, generally seen as the targets of its satire).[88] Offenbach and his librettist Hector Crémieux seized on this free publicity, and joined in a lively public debate in the columns of the Parisian daily newspaper Le Figaro.[89] Janin's indignation made the public agog to see the work, and the box office takings were prodigious. Among those who wanted to see the satire of the emperor was the emperor himself, who commanded a performance in April 1860.[89] Despite many great successes during the rest of Offenbach's career, Orphée aux enfers remained his most popular. Gammond lists among the reasons for its success, "the sweeping waltzes" reminiscent of Vienna but with a new French flavour, the patter songs, and "above all else, of course, the can-can which had led a naughty life in low places since the 1830s or thereabouts and now became a polite fashion, as uninhibited as ever."[90]

In the 1859 season, the Bouffes-Parisiens presented new works by composers including Flotow, Jules Erlanger, Alphonse Varney, Léo Delibes, and Offenbach himself. Of Offenbach's new pieces, Geneviève de Brabant though initially only a mild success, was later revised and gained much popularity where the duet of the two gendarmes became a favourite number in England and France and the basis for the Marines' Hymn in the U.S.[91]

Early 1860s

The 1860s were Offenbach's most successful decade. At the beginning of 1860, he was granted French citizenship by the personal command of Napoleon III,[92] and the following year he was appointed a Chevalier of the Légion d’Honneur; this appointment scandalised those haughty and exclusive members of the musical establishment who resented such an honour for a composer of popular light opera.[93] Offenbach began the decade with his only stand-alone ballet, Le papillon ("The Butterfly"), produced at the Opéra in 1860. It achieved what was then a successful run of 42 performances, without, as the biographer Andrew Lamb says, "giving him any greater acceptance in more respectable circles."[4] Among other operettas in the same year, he finally had a piece presented by the Opéra-Comique, the three-act Barkouf. It was not a success; its plot revolved around a dog, and Offenbach attempted canine imitations in his music. Neither the public nor the critics were impressed, and the piece survived for only seven performances.[94]

Apart from that setback, Offenbach flourished in the 1860s, with successes greatly outnumbering failures. In 1861 he led the company in a summer season in Vienna. Encountering packed houses and enthusiastic reviews, Offenbach found Vienna much to his liking. He even reverted, for a single evening, to his old role as a cello virtuoso at a command performance before Emperor Franz Joseph.[95] That success was followed by a failure in Berlin. Offenbach, though born a Prussian citizen, observed, "Prussia never does anything to make those of our nationality happy."[n 17] He and the company hastened back to Paris.[95] Meanwhile, among his operettas that season were the full-length Le pont des soupirs and the one-act M. Choufleuri restera chez lui le....[96]

In 1862, Offenbach's only son, Auguste (died 1883), was born, the last of five children. In the same year, Offenbach resigned as director of the Bouffes-Parisiens, handing the post over to Alphonse Varney. He continued to write most of his works for the company, with the exception of occasional pieces for the summer season at Bad Ems.[n 18] Despite problems with the libretto, Offenbach completed a serious opera in 1864, Die Rheinnixen, a hotchpotch of romantic and mythological themes. The opera was presented with substantial cuts at the Vienna Court Opera and in Cologne in 1865. It was not given again until 2002, when it was finally performed in its entirety. Since then it has been given several productions.[97] It contained one number, the "Elfenchor", described by the critic Eduard Hanslick as "lovely, luring and sensuous",[98] which Ernest Guiraud later adapted as the Barcarolle in The Tales of Hoffmann.[99] After December 1864, Offenbach wrote less frequently for the Bouffes-Parisiens, and many of his new works premiered at larger theatres.[4]

Later 1860s

Between 1864 and 1868, Offenbach wrote four of the operettas for which he is chiefly remembered: La belle Hélène (1864), La Vie parisienne (1866), La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867) and La Périchole (1868). Halévy was joined as librettist for all of them by Henri Meilhac. Offenbach, who called them "Meil" and "Hal",[100] said of this trinity: "Je suis sans doute le Père, mais chacun des deux est mon Fils et plein d'Esprit,"[101] a play on words loosely translated as "I am certainly the Father, but each of them is my Son and Wholly Spirited".[n 19]

For La belle Hélène, Offenbach secured Hortense Schneider to play the title role. Since her early success in his short operas, she had become a leading star of the French musical stage. She now commanded large fees and was notoriously temperamental, but Offenbach was adamant that no other singer could match her as Hélène.[102] Rehearsals for the premiere at the Théâtre des Variétés were tempestuous, with Schneider and the principal mezzo-soprano Léa Silly feuding, the censor fretting about the satire of the imperial court, and the manager of the theatre attempting to rein in Offenbach's extravagance with production expenses.[102] Once again the success of the piece was inadvertently assured by the critic Janin; his scandalised notice was strongly countered by liberal critics and the ensuing publicity again brought the public flocking.[103]

Barbe-bleue was a success in early 1866 and was quickly reproduced elsewhere. La Vie parisienne later in the same year was a new departure for Offenbach and his librettists; for the first time in a large-scale piece they chose a modern setting, instead of disguising their satire under a classical cloak. It needed no accidental boost from Janin but was an instant and prolonged success with Parisian audiences, although its very Parisian themes made it less popular abroad. Gammond describes the libretto as "almost worthy of [W.S.] Gilbert", and Offenbach's score as "certainly his best so far".[104] The piece starred Zulma Bouffar, who began an affair with the composer that lasted until at least 1875.[105]

In 1867, Offenbach had his greatest success. The premiere of La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein, a satire on militarism,[106] took place two days after the opening of the Paris Exhibition, an even greater international draw than the 1855 exhibition which had helped him launch his composing career.[107] The Parisian public and foreign visitors flocked to the new operetta. Sovereigns who saw the piece included the King of Prussia accompanied by his chief minister, Otto von Bismarck. Halévy, with his experience as a senior civil servant, saw more clearly than most the looming threat from Prussia; he wrote in his diary, "Bismarck is helping to double our takings. This time it's war we're laughing at, and war is at our gates."[108] La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein was followed quickly by a series of successful pieces: Robinson Crusoé, Geneviève de Brabant (revised version; both 1867), Le château à Toto, Le pont des soupirs (revised version) and L'île de Tulipatan (all in 1868).[109]

In October 1868, La Périchole marked a transition in Offenbach's style, with less exuberant satire and more human romantic interest.[110] Lamb calls it Offenbach's "most charming" score.[111] There was some critical grumbling at the change, but the piece, with Schneider in the lead, did good business.[112] It was quickly produced in Europe and both North and South America.[113][114] Of the pieces that followed it at the end of the decade, Les brigands (1869) was another work that leaned more to romantic comic opera than to opéra bouffe. It was well received, but has not subsequently been revived as often as Offenbach's best-known operettas.[110]

War and aftermath

Offenbach returned hurriedly from Ems and Wiesbaden before the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. He then went to his home in Étretat and arranged for his family to move to the safety of San Sebastián in northern Spain, joining them shortly afterwards.[115][116] Having risen to fame under Napoleon III, satirised him, and been rewarded by him, Offenbach was universally associated with the old régime: he was known as "the mocking-bird of the Second Empire".[117] When the empire fell in the wake of Prussia's crushing victory at Sedan (1870), Offenbach's music was suddenly out of favour. France was swept by violently anti-German sentiments, and despite his French citizenship and Légion d'honneur, his birth and upbringing in Cologne made him suspect. His operettas were now frequently vilified as the embodiment of everything superficial and worthless in Napoleon III's régime.[38] La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein was banned in France because of its antimilitarist satire.[118]

Although his Parisian audience deserted him, Offenbach had by now become highly popular in England. John Hollingshead of the Gaiety Theatre presented Offenbach's operettas to large and enthusiastic audiences.[119] Between 1870 and 1872, the Gaiety produced 15 of his works. At the Royalty Theatre, Richard D'Oyly Carte presented La Périchole in 1875.[120] In Vienna, too, Offenbach works were regularly produced. While the war and its aftermath ravaged Paris, the composer supervised Viennese productions and travelled to England as the guest of the Prince of Wales.[121]

By the end of 1871 life in Paris had returned to normal, and Offenbach ended his voluntary exile. His new works Le roi Carotte (1872) and La jolie parfumeuse (1873) were modestly profitable, but lavish revivals of his earlier successes did better business. He decided to go back into theatre management and took over the Théâtre de la Gaîté in July 1873.[122] His spectacular revival of Orphée aux enfers there was highly profitable; an attempt to repeat that success with a new, lavish version of Geneviève de Brabant proved less popular.[123] Along with the costs of extravagant productions, collaboration with the dramatist Victorien Sardou culminated in financial disaster. An expensive production of Sardou's La haine in 1874, with incidental music by Offenbach, failed to attract the public to the Gaîté, and Offenbach was forced to sell his interests in the Gaîté and to mortgage future royalties.[124]

In 1876 a successful tour of the United States in connection with its Centennial Exhibition enabled Offenbach to recover some of his losses and pay his debts. Beginning with a concert at Gilmore's Garden before a crowd of 8,000 people, he gave a series of more than 40 concerts in New York and Philadelphia. To circumvent a Philadelphia law forbidding entertainments on Sundays, he disguised his operetta numbers as liturgical pieces and advertised a "Grand Sacred Concert by M. Offenbach". "Dis-moi, Vénus" from La belle Hélène became a "Litanie", and other equally secular numbers were billed as "Prière" or "Hymne".[125] The local authorities were not deceived, and the concert did not take place.[126] At Booth's Theatre, New York, Offenbach conducted La vie parisienne[127] and his recent (1873) La jolie parfumeuse.[4] He returned to France in July 1876, with profits that were handsome but not spectacular.[53]

Offenbach's later operettas enjoyed renewed popularity in France, especially Madame Favart (1878), which featured a fantasy plot about the real-life French actress Marie Justine Favart, and La fille du tambour-major (1879), which was the most successful of his operettas of the 1870s.[128]

Last years

Profitable though La fille du tambour-major was, composing it left Offenbach less time to work on his cherished project, the creation of a successful serious opera. Since the beginning of 1877, he had been working when he could on a piece based on a stage play, Les contes fantastiques d'Hoffmann, by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré. Offenbach had suffered from gout since the 1860s, often being carried into the theatre in a chair. Now in failing health, he was conscious of his own mortality and wished passionately to live long enough to complete the opera Les contes d'Hoffmann ("The Tales of Hoffmann"). He was heard saying to Kleinzach, his dog, "I would give everything I have to be at the première".[129] However, Offenbach did not live to finish the piece. He left the vocal score substantially complete and had made a start on the orchestration. Ernest Guiraud, a family friend, assisted by Offenbach's 18-year-old son Auguste, completed the orchestration, making significant changes as well as the substantial cuts demanded by the Opéra-Comique's director, Carvalho.[130][n 20] The opera was first seen at the Opéra-Comique on 10 February 1881; Guiraud added recitatives for the Vienna premiere, in December 1881, and other versions were made later.[130]

Offenbach died in Paris in 1880 at the age of 61. His cause of death was certified as heart failure brought on by acute gout. He was given a state funeral; The Times wrote, "The crowd of distinguished men that accompanied him on his last journey amid the general sympathy of the public shows that the late composer was reckoned among the masters of his art."[131] He is buried in the Montmartre Cemetery.[132]

Works

In The Musical Times, Mark Lubbock wrote in 1957:

Offenbach's music is as individually characteristic as that of Delius, Grieg or Puccini – together with range and variety. He could write straightforward "singing" numbers like Paris' song in La Belle Hélène, "Au mont Ida trois déesses"; comic songs like General Boum's "Piff Paff Pouf" and the ridiculous ensemble at the servants' ball in La Vie Parisienne, "Votre habit a craqué dans le dos". He was a specialist at writing music that had a rapturous, hysterical quality. The famous can-can from Orphée aux Enfers has it, and so has the finale of the servants' party ... which ends with the delirious song "Tout tourne, tout danse'". Then, as a contrast, he could compose songs of a simplicity, grace and beauty like the Letter Song from La Périchole, "Chanson de Fortunio", and the Grand Duchess's tender love song to Fritz: "Dites-lui qu'on l'a remarqué distingué".[133]

Among other well-known Offenbach numbers are the Doll Song, "Les oiseaux dans la charmille" (The Tales of Hoffmann); "Voici le sabre de mon père" and "Ah! Que j'aime les militaires" (La Grande Duchesse de Gerolstein); and "Tu n'es pas beau" in La Périchole, which Lamb notes was Offenbach's last major song for Hortense Schneider.[134][n 21]

Operettas

By his own reckoning, Offenbach composed more than 100 operas.[136][n 22] Both the number and the noun are open to question: some works were so extensively revised that he evidently counted the revised versions as new, and commentators generally refer to all but a few of his stage works as operettas, rather than operas. Offenbach reserved the term opérette (English: operetta)[n 23] or opérette bouffe for some of his one-act works, more often using the term opéra bouffe for his full-length ones (though there are a number of one- and two-act examples of this type). It was only with the further development of the Operette genre in Vienna after 1870 that the French term opérette began to be used for works longer than one act.[139] Offenbach also used the term opéra-comique for at least 24 of his works in either one, two or three acts.[140]

Offenbach's earliest operettas were one-act pieces for small casts. More than 30 of these were presented before his first full-scale "opéra bouffon", Orphée aux enfers, in 1858, and he composed over 20 more of them during the rest of his career.[4][141] Lamb, following the precedent of Henseler's 1930 study of the composer, divides the one-act pieces into five categories: "(i) country idylls; (ii) urban operettas; (iii) military operettas; (iv) farces; and (v) burlesques or parodies."[142] Offenbach enjoyed his greatest success in the 1860s. His most popular operettas from the decade have remained among his best known.[4]

- Texts and word setting

The first ideas for plots usually came from Offenbach, with his librettists working on lines agreed with him. Lamb writes, "In this respect Offenbach was both well served and skilful at discovering talent. Like Sullivan, and unlike Johann Strauss II, he was consistently blessed with workable subjects and genuinely witty librettos."[4] He took advantage of the rhythmic flexibility of the French language, but sometimes took this to extremes, forcing words into unnatural stresses.[143] Harding comments that he "wrought much violence on the French language".[144] A frequent characteristic of Offenbach's word setting was the nonsensical repetition of isolated syllables of words for comic effect; an example is the quintet for the kings in La belle Hélène: "Je suis l'époux de la reine/Poux de la reine/Poux de la reine" and "Le roi barbu qui s'avance/Bu qui s'avance/Bu qui s'avance."[n 24]

- Musical structure

In general, Offenbach followed simple, established forms. His melodies are usually short and unvaried in their basic rhythm, rarely, in Hughes's words, escaping "the despotism of the four-bar phrase".[145] In modulation Offenbach was similarly cautious; he rarely switched a melody to a remote or unexpected key, and kept mostly to a tonic–dominant–subdominant pattern.[146] Within these conventional limits, he employed greater resource in his varied use of rhythm; in a single number he would contrast rapid patter for one singer with a broad, smooth phrase for another, illustrating their different characters.[146] Similarly, he often switched quickly between major and minor keys, effectively contrasting characters or situations.[147] When he wished to, Offenbach could use unconventional techniques, such as the leitmotiv, used throughout to accompany the eponymous Docteur Ox (1877)[148] and to parody Wagner in La carnaval des revues (1860).[149]

- Orchestration

In his early pieces for the Bouffes-Parisiens, the size of the orchestra pit had restricted Offenbach to an orchestra of 16 players.[150] He composed for flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, two horns, piston, trombone, timpani and percussion and a small string section of seven players.[151] After moving to the Salle Choiseul he had an orchestra of 30 players.[151] The musicologist and Offenbach specialist Jean-Christophe Keck notes that when larger orchestras were available, either in bigger Paris theatres or in Vienna or elsewhere, Offenbach would compose, or rearrange existing music, accordingly. Surviving scores show his instrumentation for additional wind and brass, and even extra percussion. When they were available he wrote for cor anglais, harp, and, exceptionally, Keck records, an ophicleide (Le Papillon), tubular bells (Le carnaval des revues), and a wind machine (Le voyage dans la lune).[151]

Hughes describes Offenbach's orchestration as "always skilful, often delicate, and occasionally subtle." He instances Pluton's song in Orphée aux enfers,[n 25] introduced by a three-bar phrase for solo clarinet and solo bassoon in octaves immediately repeated on solo flute and solo bassoon an octave higher.[152] In Keck's view, "Offenbach's orchestral scoring is full of details, elaborate counter-voices, minute interactions coloured by interjections of the woodwinds or brass, all of which establish a dialogue with the voices. His refinement of design equals that of Mozart or Rossini."[151]

- Compositional method

Offenbach often composed amidst noise and distractions. According to Keck, Offenbach would first make a note of melodies a libretto suggested to him in a notebook or straight onto the librettist's manuscript. Next using full score manuscript paper he wrote down vocal parts in the centre, then a piano accompaniment at the bottom possibly with notes on orchestration. When Offenbach felt sure the work would be performed, he began full orchestration, often employing a codified system.[153]

- Parody and influences

Offenbach was well known for parodying other composers' music. Some of them saw the joke and others did not. Adam, Auber and Meyerbeer enjoyed Offenbach's parodies of their scores.[53] Meyerbeer made a point of attending all Bouffes-Parisiens productions, always seated in Offenbach's private box.[65] Among the composers who were not amused by Offenbach's parodies were Berlioz and Wagner.[154] Offenbach mocked Berlioz's "strivings after the antique",[155] and his initial light-hearted satire of Wagner's pretensions later hardened into genuine dislike.[156] Berlioz reacted by bracketing Offenbach and Wagner together as "the product of the mad German mind",[154] and Wagner, ignoring Berlioz, retaliated by writing some unflattering verses about Offenbach.[154]

In general, Offenbach's parodistic technique was simply to play the original music in unexpected and incongruous circumstances. He slipped the banned revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise into the chorus of rebellious gods in Orphée aux enfers, and quoted the aria "Che farò" from Gluck's Orfeo in the same work; in La belle Hélène he quoted the patriotic trio from Rossini's Guillaume Tell and parodied himself in the ensemble for the kings of Greece, in which the accompaniment quotes the rondeau from Orphée aux enfers. In his one act pieces, Offenbach parodied Rossini's "Largo al factotum" and familiar arias by Bellini. In Croquefer (1857), one duet consists of quotations from Halévy's La Juive and Meyerbeer's Robert le Diable and Les Huguenots.[142][157] Even in his later, less satirical period, he included a parodic quotation from Donizetti's La fille du régiment in La fille du tambour-major.[4]

Other examples of Offenbach's use of incongruity are noted by the critic Paul Taylor: "In La belle Hélène, the kings of Greece denounce Paris as 'un vil séducteur' to a waltz tempo that is itself unsuitably seductive ... the potty-sounding phrase 'L'homme à la pomme' becomes the absurd nucleus of a big cod-ensemble."[158] Another lyric set to absurdly ceremonious music is "Votre habit a craqué dans le dos" ("Your coat has split down the back") in La vie parisienne.[15] The Grand Duchess of Gérolstein's rondo "Ah! Que j'aime les militaires" is rhythmically and melodically similar to the finale of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony, but it is not clear whether the similarity is parodic or coincidental.[15]

In Offenbach's last decade, he took note of a change in public taste: a simpler, more romantic style was now preferred. Harding writes that Lecocq had successfully moved away from satire and parody, returning to "the genuine spirit of opéra-comique and its peculiarly French gaiety."[144] Offenbach followed suit in a series of 20 operettas; the conductor and musicologist Antonio de Almeida names the finest of these as La fille du tambour-major (1879).[128]

Other works

Of Offenbach's two serious operas, Die Rheinnixen, a failure, was not revived until the 21st century.[159] His second attempt, The Tales of Hoffmann, was originally intended as a grand opera.[160] When the work was accepted by Léon Carvalho for production at the Opéra-Comique, Offenbach agreed to make it an opéra comique with spoken dialogue. It was incomplete when he died;[161] Faris speculates that, but for Georges Bizet's premature death, Bizet rather than Guiraud would have been asked to complete the piece and would have done so more satisfactorily.[162] The critic Tim Ashley writes, "Stylistically, the opera reveals a remarkable amalgam of French and German influences ... Weberian chorales preface Hoffmann's narrative. Olympia delivers a big coloratura aria straight out of French grand opera, while Antonia sings herself to death to music reminiscent of Schubert."[38]

Although he wrote ballet music for many of his operettas, Offenbach wrote only one ballet, Le papillon. The score was much praised for its orchestration, and it contained one number, the "Valse des rayons", that became an international success.[163] Between 1836 and 1875 he composed several individual waltzes and polkas, and suites of dances.[164] They include a waltz, Abendblätter ("Evening Papers") composed for Vienna with Johann Strauss's Morgenblätter ("Morning Papers") as a companion piece.[165] Other orchestral compositions include a piece in 17th-century style with cello solo, which became a standard work of the cello repertoire. Little of Offenbach's non-operatic orchestral music has been regularly performed since his death.[32]

Offenbach composed more than 50 non-operatic songs between 1838 and 1854, most of them to French texts, by authors including Alfred de Musset, Théophile Gautier and Jean de La Fontaine, and also ten to German texts. Among the most popular of these songs are "À toi" (1843), dedicated to the young Hérminie d'Alcain as an early token of his love.[166] An Ave Maria for soprano solo was recently rediscovered at the Bibliothèque nationale de France.[167]

Arrangements

Although the overtures to Orphée aux enfers and La belle Hélene are well known and frequently recorded, the scores usually performed and recorded were not composed by Offenbach, but were arranged by Carl Binder and Eduard Haensch, respectively, for the Vienna premieres of the two works. Offenbach's own preludes are much shorter.[168]

In 1938, Manuel Rosenthal assembled the popular ballet Gaîté Parisienne from his own orchestral arrangements of melodies from Offenbach's stage works, and in 1953 the same composer assembled a symphonic suite, Offenbachiana, also from music by Offenbach.[169] Jean-Christophe Keck regards the 1938 work as "no more than a vulgarly orchestrated pastiche";[170] in Gammond's view, however, it does "full justice" to Offenbach.[171]

Legacy and reputation

Influence

The musician and author Fritz Spiegl wrote in 1980, "Without Offenbach there would have been no Savoy Opera … no Die Fledermaus or Merry Widow.[172] The two creators of the Savoy operas, the librettist, Gilbert, and the composer, Sullivan, were both indebted to Offenbach and his partners for their satiric and musical styles, even borrowing plot components.[173] For example, Faris argues that the mock-oriental Ba-ta-clan influenced The Mikado, including its character names: Offenbach's Ko-ko-ri-ko and Gilbert's Ko-Ko;[174] Faris also compares Le pont des soupirs (1861) and The Gondoliers (1889): "in both works there are choruses à la barcarolle for gondoliers and contadini [in] thirds and sixths; Offenbach has a Venetian admiral telling of his cowardice in battle; Gilbert and Sullivan have their Duke of Plaza-Toro who led his regiment from behind."[93] Offenbach's Les Géorgiennes (1864), like Gilbert and Sullivan's Princess Ida (1884), depicts a female stronghold challenged by males in disguise.[175][n 26] The best-known instance in which a Savoy opera draws on Offenbach's work is The Pirates of Penzance (1879), where both Gilbert and Sullivan follow the lead of Les brigands (1869) in their treatment of the police, plodding along ineffectually in heavy march-time.[110] Les brigands was presented in London in 1871, 1873 and 1875; for the first of these, Gilbert made an English translation of Meilhac and Halévy's libretto.[110]

However much the young Sullivan was influenced by Offenbach,[n 27] the influence was evidently not in only one direction. Hughes observes that two numbers in Offenbach's Maître Péronilla (1878) bear "an astonishing resemblance" to "My name is John Wellington Wells" from Gilbert and Sullivan's The Sorcerer (1877).[179]

It is not clear how directly Offenbach influenced Johann Strauss. He had encouraged Strauss to turn to operetta when they met in Vienna in 1864, but it was not until seven years later that Strauss did so.[180] However, Offenbach's operettas were well established in Vienna, and Strauss worked on the lines established by his French colleague; in 1870s Vienna, an operetta composer who did not do so was quickly called to order by the press.[180] In Gammond's view, the Viennese composer most influenced by Offenbach was Franz von Suppé, who studied Offenbach's works carefully and wrote many successful operettas using them as a model.[181]

In his 1957 article, Lubbock wrote, "Offenbach is undoubtedly the most significant figure in the history of the 'musical'," and traced the development of musical theatre from Offenbach to Irving Berlin and Rodgers and Hammerstein, via Franz Lehár, André Messager, Sullivan and Lionel Monckton.[133]

Reputation

During Offenbach's lifetime, and in the obituary notices in 1880, fastidious critics (dubbed "Musical Snobs Ltd" by Gammond) showed themselves at odds with public appreciation.[182] In a 1980 article in The Musical Times, George Hauger commented that those critics not only underrated Offenbach, but wrongly supposed that his music would soon be forgotten.[183] Although most critics of the time made that erroneous assumption, a few perceived Offenbach's unusual quality; in The Times, Francis Hueffer wrote, "none of his numerous Parisian imitators has ever been able to rival Offenbach at his best."[184] Nevertheless, the paper joined in the general prediction: "It is very doubtful whether any of his works will survive."[184] The New York Times shared this view: "That he had the gift of melody in a very extraordinary degree is not to be denied, but he wrote currente calamo,[n 28] and the lack of development of his choicest inspirations will, it is to be feared, keep them from reaching even the next generation".[185] After the posthumous production of The Tales of Hoffmann, The Times partially reconsidered its judgment, writing, "Les Contes de Hoffmann [will] confirm the opinion of those who regard him as a great composer in every sense of the word".[131] It then lapsed into what Gammond calls "Victorian sanctimoniousness"[186] by taking it for granted that the opera "will uphold Offenbach's fame long after his lighter compositions have passed out of memory."[187]

The critic Sacheverell Sitwell compared Offenbach's lyrical and comic gifts to those of Mozart and Rossini.[188] Friedrich Nietzsche called Offenbach both an "artistic genius" and a "clown", but wrote that "nearly every one" of Offenbach's works achieves half a dozen "moments of wanton perfection". Émile Zola commented on Offenbach and his work in a novel (Nana)[189] and an essay, "La féerie et l'opérette IV/V".[190] While granting that Offenbach's best operettas are full of grace, charm and wit, Zola blames Offenbach for what others have made out of the genre. Zola calls operetta a "public enemy" and a "monstrous beast". While some critics saw the satire in Offenbach's works as a social protest, an attack against the establishment, Zola saw the works as a homage to the social system in the Second Empire.[190]

Otto Klemperer was an admirer; late in life he reflected: "At the Kroll we did La Périchole. That's a really delightful score. So is Orpheus in the Underworld and Belle Hélène. Those who called him 'The Mozart of the Boulevards' were not much mistaken".[191] Debussy, Bizet, Mussorgsky and Rimsky-Korsakov loved Offenbach's operettas.[192] Debussy rated them higher than The Tales of Hoffmann: "The one work in which [Offenbach] tried to be serious met with no success."[n 29] A London critic wrote, on Offenbach's death:

I somewhere read that some of Offenbach's latest work shows him to be capable of more ambitious work. I, for one, am glad he did what he did, and only wish he had done more of the same.[196]

Efforts to present critical editions of Offenbach's works have been hampered by the dispersion of his autograph scores to several collections after his death, some of which do not grant access to scholars.[n 30]

Notes and references

Notes

- Biographers are divided on the original form of his given name: Faris (1980),[1] Pourvoyeur (1994),[2] Yon (2000),[3] and Lamb (Grove's Dictionary, 2007)[4] give it as "Jacob"; Henseler (1930),[5] Kracauer (1938),[6] Almeida (1976)[7] Gammond (1980),[8] and Harding (1980)[9] give it as "Jakob". Gammond reproduces the title page of Offenbach's Opus 1 (1833), where his name is printed as "Jacob Offenbach".[10]

- From 1815 the western German province of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, of which Cologne was the capital city, was part of the kingdom of Prussia.

- Gammond and Almeida state that Isaac was already using the surname Offenbach by the time of his marriage in 1805. Yon states that the formal adoption of the surname in 1808 was in compliance with a Napoleonic decree requiring Jewish surnames to be regularised.[14]

- Offenbach was accustomed to giving the year of his birth as 1821, possibly a legacy of his days as a child prodigy, when his age was routinely understated for effect.[8][15]

- Yon notes that although foreign nationality was a barrier to entry for the Conservatoire's prestigious competitions, it was not such an obstacle to enrolment as a student.[18]

- "a quitté voluntairement".[23] Harding gives the date as 24 December.[24]

- Other British publications including The Times and The Manchester Guardian reported on this command performance, but the biographer Peter Gammond was told by the royal archivist that no reference to a performance by Offenbach on the date in question could be found in the official archives.[36]

- In addition to a long affair with Zulma Bouffar, Offenbach was known to have had shorter affairs with the singers Marie Cico and Louise Valtesse.[41]

- They were Le trésor à Mathurin, Pépito, and Luc et Lucette.[4]

- The authorities spelling the name as "Oyayaye" include Faris,[54] Lamb,[4] Pourvoyeur,[55] and Yon;[56] Gammond,[57] Harding,[58] and Kracauer[59] spell the name as "Oyayaie".

- According to his friend, the photographer Nadar, Offenbach had made 3,997 visits to the various directors of the Opéra-Comique.[31]

- Andre Lamb gives the capacity of the Salle Lacaze as 300; Peter Gammond gives it as 50.[4][62]

- Offenbach was licensed to put on "harlequinades, pantomimes, comic scenes, conjuring tricks, dances, shadow shows, puppet plays and songs" – subject to the maximum of three singers or actors stipulated.[63]

- Rossini wrote a short piano work dedicated to Offenbach: the Petit caprice (style Offenbach) in can-can rhythm, in which the performer is directed to use only the index and little finger of each hand.[71] The biographers who identify Rossini as the originator of the "Mozart of the Champs-Élysées" tag include Faris,[72] Gammond,[73] Harding,[74] Kracauer,[75] and Yon.[76] Wagner is also thought by some to have used this nickname for Offenbach,[77] although for most of his life Offenbach's music was anathema to him; it was only in the last year of his life that Wagner wrote, "Look at Offenbach. He writes like the divine Mozart".[78]

- "Où l'Italien donnait carrière à sa verve et à son imagination, le Français s'est piqué de malice, de bon sens et de bon goût; où son modèle sacrifiait exclusivement à la gaité, il a sacrifié surtout à l'esprit."[81]

- "Des pièces de velours se sont englouties dans le salle, les costumes ont dévoré des lés de satin."[85] The English translation is given in Faris.[80]

- "La prusse ne ferait jamais le bonheur de nos nationaux".[95]

- The Bad Ems pieces were, Les bavards (1862), Il signor Fagotto (1863), Lischen et Fritzchen (1863), Le fifre enchanté, ou Le soldat (1864), Jeanne qui pleure et Jean qui rit (1864), Coscoletto, ou Le lazzarone (1865), and La permission de dix heures (1867). Most of them were played at the Bouffes-Parisiens in the winter season after their premieres.[4]

- Literally, "No doubt I am the Father; each of the two is my Son and Full of Verve" – "esprit" meaning both "[Holy] Spirit" and "wit", and "Plein d'Esprit" rhyming with "Saint Esprit".

- Guiraud added recitatives in place of spoken dialogue for the Vienna premiere. According to Keck, the rehearsal on 1 February lasted four and a half hours, and Carvalho decided to cut the Venice act, redistributing some of its music.[130] The orchestral parts were destroyed in the Opéra-Comique fire of 1887. Using surviving manuscripts, and with the researches of Almeida and others, a score closer to Offenbach's conception has been possible, but, in Lamb's phrase, "there can never be a definitive score of a work that Offenbach never quite completed".[4]

- The Offenbach expert Antonio de Almeida included the following less well-known numbers in his selection of Offenbach's best work: "Chanson de Fortunio" (from the piece of the same title); Sérénade (Pont des soupirs); Rondo – "Depuis la rose nouvelle" (Barbe-bleue); "Ronde des carabiniers" (Les brigands); Rondeau – "J'en prendrai un, deux, trois" (Pomme d'Api); "Couplets du petit bonhomme" and "Couplets de l'alphabet" (Madame l'archiduc); and the valse "Monde charmant que l'on ignore" (Le voyage dans le lune).[135]

- In 1911, The Musical Times cited Offenbach as the seventh most prolific operatic composer, with 103 operas (one more than Sir Henry Bishop and six fewer than Baldassare Galuppi). The most prolific was said to be Wenzel Müller with 166.[137]

- The term opérette was first used in 1856 for Jules Bovéry's Madame Mascarille.[7] Gammond categorises Cigarette, a work premiered in London, with the English term "operetta"; Grove does not mention it.[4][138]

- In English, "I am the husband of the queen" and "The bearded king who comes forward", in which the second syllables of "époux" (husband) and "barbu" (bearded) are nonsensically repeated. Lamb instances a variant of such wordplay in La Périchole:

- Aux maris ré,

- Aux maris cal,

- Aux maris ci,

- Aux maris trants,

- Aux maris récalcitrants. ("Husbands who are re– , husbands who are cal– , husbands who are ci– , husbands who are trant, husbands who are recalcitrant...")[4]

- In the 1874 revision this number is a duet for Pluton and Euridice.

- Gilbert's plot line, unlike that of Offenbach's librettist Jules Moinaux, was based on an 1847 Tennyson poem, "The Princess".[176]

- In 1875, two of Sullivan's short operettas, The Zoo and Trial by Jury were playing in London as companion pieces to longer Offenbach works, Les Géorgiennes and La Périchole.[177] Trial by Jury was written specifically as an afterpiece for that production of La Périchole.[178]

- Latin, literally, "with the pen running on" – meaning "extempore; without deliberation or hesitation." (Oxford English Dictionary)

- Debussy wrote this in 1903, when The Tales of Hoffmann, after initial success, with 101 performances in its first year, had become neglected.[193] A production by Thomas Beecham at His Majesty's Theatre, London, in 1910 restored the work to the mainstream operatic repertoire, where it has remained.[194][195]

- Although Auguste catalogued the sketches and manuscripts after his father's death, when his widow died the surviving daughters battled over the papers.[197] Many of his papers were involved in the collapse of the city archives in Cologne in 2009.[198]

References

- Faris, p. 21

- Pourvoyeur, p. 28

- Yon, p. 49

- Lamb, Andrew. "Offenbach, Jacques (Jacob)", Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, 2007, accessed 8 July 2011 (subscription required)

- Henseler, title page et passim

- Kracauer, p. 38

- Almeida, p. iv

- Gammond, p. 15

- Harding, pp. 9–11

- Gammond, p. 14

- Gammond, p. 13

- Faris, p. 14

- Faris, p. 17

- Gammond, p. 13, Almeida, p. ix, and Yon, p. 10

- Grovlez, Gabriel. "Jacques Offenbach: A Centennial Sketch", Archived 9 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 3 (July 1919), pp. 329–337 (subscription required)

- Faris, p. 18

- Faris, p. 19

- Yon, p. 23

- Faris, p. 20

- Gammond, p. 17

- Harding, p. 19

- Gammond, p. 18

- Faris, p. 224

- Harding, p. 20

- Harding, p. 21

- Gammond, p. 19

- Gammond, pp. 19–20

- Harding, p. 27

- Faris, pp. 23 and 257

- Faris, p. 23 and Gammond, pp. 22–23

- Faris, p. 28

- Gammond, p. 28

- Harding, p. 39

- "Madame Puzzi's Concert", The Era, 19 May 1844, p. 5

- The Illustrated London News, 8 June 1844, p. 370

- Gammond, pp. 28–29

- "Varieties", The Manchester Guardian 12 June 1844, p. 5; and "Madame Dulcken's Concert", The Times, 12 June 1844, p. 7

- Ashley, Tim. "The cursed opera", Archived 8 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 9 January 2004

- Harding, p. 40

- Harding, p. 52 and Faris, p. 103

- Yon, pp. 214, 393 and 407

- De Joncières, Victorin, quoted in Gammond, p. 30

- Gammond, p. 30

- Gammond, p. 32

- Horne, pp. 225–226

- Gammond, p. 35

- Gammond, p. 34

- Harding, p. 51

- Harding, p. 54

- Gammond, pp. 35–36

- Debussy, quoted in Faris, p. 28

- Huebner, Steven. "Review: Hervé: Un Musicien paradoxal (1825–1892)," Archived 15 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine Notes, Second Series, Vol. 50, No. 3 (March 1994), pp. 972–973 (subscription required); Harding, pp. 59–61; and Kracauer, pp. 138–139

- Teneo, Martial, and Theodore Baker. "Jacques Offenbach: His Centenary", Archived 15 August 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 6, No. 1 (January 1920), pp. 98–117 (subscription required)

- Faris, p. 49

- Pourvoyeur, p. 241

- Yon, p. 141

- Gammond, p. 36

- Harding, p. 61

- Kracauer, pp. 139–140

- Yon, p. 111

- Offenbach, quoted in Gammond, p. 37 and Bekker, pp. 18–19. Various editions of Gammond give the spelling as "Lacaza" and "Lazaca". Bekker gives it as "Lacaze"

- Gammond, p. 37

- Harding, p. 63

- Faris, pp. 49–51

- Faris, Alexander. "The birth of the Bouffes-Parisiens", The Times, 11 October 1980, p. 6

- Harding, p. 66

- Gammond, p. 39

- Yon, pp. 760–762

- Levin, p. 401

- Harding, p. 253

- Ragni, Sergio. "Rossini: Complete Piano Edition, Volume 2" Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Chandos Records, accessed 16 July 2011

- Faris, p. 66

- Gammond, p. 45

- Harding, p. 82

- Kracauer, p. 164

- Yon, p. 175

- Pourvoyeur, p. 180

- Faris, p. 27

- Yon, p. 179

- Faris, p. 58

- Offenbach, Jacques. "Concours pour une opérette en un acte", Archived 15 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine Le Figaro, 17 July 1856

- Curtiss, Mina. "Bizet, Offenbach, and Rossini", Archived 21 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Quarterly, Vol. 40, No. 3 (July 1954), pp. 350–359 (subscription required)

- Gammond, p. 42

- Gammond, p. 43

- Martinet, p. 44

- Gammond, p. 46

- Harding, p. 110

- Faris, p. 71

- Gammond, p. 54

- Gammond, p. 56

- Gammond, p. 57

- Kracauer, p. 209

- Faris, p. 84

- Gammond, p. 63

- Gammond, p. 70

- Gänzl, Kurt. "Jacques Offenbach" Archived 27 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Operetta Research Center, 27 February 2010, accessed 25 July 2011

- OEK Dokumentation 2002–2006, Jacques Offenbach, Les Fées du Rhin Archived 11 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Boosey & Hawkes, Bote Bock (in German), 2006, p. 59

- Gammond, p. 78

- Faris, p. 24

- Faris, p. 51

- "1864: Et puis Offenbach vint" Archived 3 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Théâtre des Variétés, Paris (in French), accessed 9 July 2011

- Gammond, p. 80

- Gammond, p. 81

- Gammond, p. 87

- Harding, p. 141

- Gammond, p. 89

- Harding, pp. 165–168

- Harding, p. 172

- Lamb, Andrew. "Pont des soupirs, Le", New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, accessed 23 June 2013 (subscription required) (Le Pont de soupirs); and Gammond, pp. 93–94 (Robinson Crusoé, Geneviève de Brabant, Le château à Toto and L'île de Tulipatan)

- Gammond, p. 97

- Lamb, Andrew. "La Périchole" in The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Macmillan, London & New York, 1997.

- Yon, p. 374

- La Périchole, L'Avant-Scène Opéra, No. 66, August 1984

- La Périchole at the IBDB database

- Yon, p. 396

- Faris, p. 164

- Canning, Hugh. "I love Paris", Archived 8 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Sunday Times, 5 November 2000

- Clements, Andrew. "Offenbach: La Grande-Duchesse de Gérolstein", Archived 28 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 14 October 2005

- Gammond, p. 100

- Young, pp. 105–106

- Gammond, p. 102

- Gammond, p. 104

- Harding, p. 198

- Harding, pp. 199–200, and Yon, p. 502

- O'Connor, Patrick. "The Embodiment of Success", The Times Literary Supplement, 10 October 1980, p. 1128

- Gammond, p. 116

- "Amusements – The Opera Bouffe", Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 13 June 1876

- Almeida, p. xxi

- Faris, p. 192

- Keck, J-C. Genèse et légendes. In : L'Avant-Scène Opéra – Les Contes d'Hoffmann. Éditions Premières Loges, Paris, No 235, 2006.

- "France", The Times, 8 October 1880, p. 3

- "Cimetière de Montmartre" Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Parisinfo, Site officiel de l'Office du Tourisme et des Congrès, accessed 23 June 2013

- Lubbock, Mark. "The Music of 'Musicals'", Archived 31 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Times, Vol. 98, No. 1375 (September 1957), pp. 483–485 (subscription required)

- Lamb, Andrew. "Périchole, La." The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, accessed 26 August 2011 (subscription required)

- Almeida, pp. v and vi

- "Offenbach's hundred operas", The Era, 11 February 1877, p. 5

- Towers, John. "Who composed the greatest number of operas?" The Musical Times, 1 August 1911, p. 527 (subscription required) Archived 10 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Gammond, p. 147

- Lamb, Andrew. "Operetta" Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online, accessed 28 April 2018 (subscription required)

- Gammond, pp. 145–156

- Gammond, pp. 156–157

- Lamb, Andrew. "Offenbach in One Act", Archived 14 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Times, Vol. 121, No. 1652 (October 1980), pp. 615–617 (subscription required)

- Hughes, p. 43

- Harding, p. 208

- Hughes, p. 46

- Hughes, p. 48

- Hughes, p. 51

- Hughes, p. 39

- Gammond, p. 59

- Faris, p. 39

- Keck, Jean-Christophe. "The need for an authentic Offenbach" Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Offenbach Edition, Keck, Boosey and Hawkes, accessed 16 July 2011

- Hughes, p. 45

- Keck, Jean-Christophe (translated by John Taylor Tuttle). Offenbach, an oeuvre boasting more than 600 works. Booklet essay for ‘Ballade Symphonique’, CD 476 8999, Universal Classics France, 2006.

- Gammond, pp. 59, 63 and 73

- Henseler, quoted in Hughes, p. 46

- Gammond, pp. 59 and 127

- Scherer, Barrymore Laurence. "Gilbert & Sullivan, Parody's Patresfamilias", Archived 24 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Wall Street Journal, 23 June 2011

- Taylor, Paul. "The judgement of Paris, France", Archived 8 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Independent, 28 November 1995

- Milnes R. "One Long Hymn to Pacifism", Opera, October 2009, pp. 1202–1206.

- Faris, pp. 203–204

- Traubner, p. 643; Faris, p. 190; Gammond, p. 127–128.

- Faris, p. 195

- Gammond, p. 62

- Gammond, p. 159

- Gammond, pp. 75–76

- Gammond, p. 26

- Ave Maria solo de Soprano. bnf.fr. 1865. Retrieved 14 January 2020.

- Gammond, p. 69

- Salter, Lionel. "Offenbach/Rosenthal – Gaîté Parisienne. Offenbachiana", Gramophone, November 1999, p. 72

- Keck, Jean-Christophe. "Offenbach Edition Keck" Archived 21 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Offenbach Edition Keck, Boosey and Hawkes, accessed 16 July 2011

- Gammond, p. 135

- Spiegl, Fritz. "Less than serious", The Times Literary Supplement, 10 October 1980, p. 1128

- Gammond, pp. 87 and 138

- Faris, p. 53

- Faris, p. 111

- Fidler, David. "Princess Ida: From Tennyson to Gilbert" Archived 8 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine. The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 8 August 2005

- Gammond, p. 113

- Ainger, pp. 101–109

- Hughes, p. 40

- Gammond, pp. 76–77

- Gammond, p. 77

- Gammond, p. 137

- Hauger, George. "Offenbach: English Obituaries and Realities", Archived 6 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Musical Times, Vol. 121, No. 1652 (October 1980), pp. 619–621 (subscription required)

- Obituary, The Times, 6 October 1880, p. 3

- "Jacques Offenbach dead – The end of the great composer of opera bouffe", Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 6 October 1880

- Gammond, p. 138

- "France", The Times, 14 February 1881, p. 5

- Ardoin, John. The Tales of Offenbach Archived 28 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine. San Francisco Opera, 1996, accessed 31 July 2011

- Zola, Émile: Nana, translated with an introduction by George Holden, Penguin Classics, London 1972

- Zola, Émile: La féerie et l'opérette IV/V in Le naturalisme au théâtre Archived 17 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, 1881 (e-book in French), accessed 31 July 2011

- Otto Klemperer talks to Alan Blyth. Gramophone, May 1970, p. 1748 and 1751

- Almeida, p. xii, and Faris, p. 195

- Faris, p. 219

- "His Majesty's Theatre – Thomas Beecham Opera Season", The Times, 13 May 1910, p. 10

- Faris, p. 221

- "The Only Jones", Judy, 13 October 1880, p. 172

- "Der Krimi geht weiter" Archived 25 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Opernwelt Mai 2012, p. 68, cited in full on Operetta Research Center Archived 25 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine (Boris Kehrmann. Gehört Offenbach nicht allen? Auch Jean-Christophe Kecks Offenbach-Edition lässt Fragen offen. 30 January 2013), accessed 25 May 2014.

- "Collapsed Cologne Archives Show Challenge of Preserving History" Archived 25 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, Deutsche Welle, accessed 25 May 2014.

Sources

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Almeida, Antonio de (1976). Offenbach's songs from the great operettas. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-23341-3.

- Bekker, Paul (1909). Jacques Offenbach (in German). Berlin: Marquardt. OCLC 458390878.

- Faris, Alexander (1980). Jacques Offenbach. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-11147-3.

- Gammond, Peter (1980). Offenbach. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-0257-2.

- Harding, James (1980). Jacques Offenbach: A Biography. London: John Calder. ISBN 978-0-7145-3835-8.

- Henseler, Anton (1930). Jakob Offenbach (in German). Berlin: M. Hesse. OCLC 559680953.

- Horne, Alistair (2003). Seven Ages of Paris. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-72577-1.

- Kracauer, Siegfried (2002) [1938]. Orpheus in Paris: Offenbach and the Paris of his time. New York: Zone Books. ISBN 978-1-890951-30-6.

- Hughes, Gervase (1962). Composers of Operetta. London: Macmillan. OCLC 460660877.

- Levin, Alicia C. (2009). "A Documentary Overview of Musical Theaters in Paris, 1830–1900". In Fauser, Annegret; Everist, Mark (eds.). Music, Theater, and Cultural Transfer. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. pp. 379–402. ISBN 978-0-226-23926-2.

- Martinet, André (1887). Offenbach: Sa vie et son oeuvre (in French). Paris: Dentu. OCLC 3574954.

- Pourvoyeur, Robert (1994). Offenbach (in French). Paris: Éditions du Seuil. ISBN 978-2-02-014433-9.

- Traubner, Richard (2001). "Offenbach, Jacques". In Holden, Amanda (ed.). The New Penguin Opera Guide. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-051475-9.

- Yon, Jean-Claude (2000). Jacques Offenbach (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 978-2-07-074775-7.

- Young, Percy M. (1971). Sir Arthur Sullivan. London: J. M. Dent. ISBN 978-0-460-03934-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jacques Offenbach. |

- Les folies Offenbach

- Offenbach Edition Keck

- Boosey and Hawkes Offenbach pages

- List of works by Offenbach at the Index to Opera and Ballet Sources Online

- Offenbach at the Musicals101 site

- Jacques Offenbach at the Internet Broadway Database

- The Jacques Offenbach Society (UK)