Witness (1985 film)

Witness is a 1985 American neo-noir[2] crime drama film directed by Peter Weir and starring Harrison Ford, Kelly McGillis, and Lukas Haas. Jan Rubeš, Danny Glover, Josef Sommer, Alexander Godunov, Patti LuPone, and Viggo Mortensen appear in supporting roles. The screenplay by William Kelley, Pamela Wallace, and Earl W. Wallace focuses on a detective protecting a young Amish boy who becomes a target after he witnesses a murder in Philadelphia.

| Witness | |

|---|---|

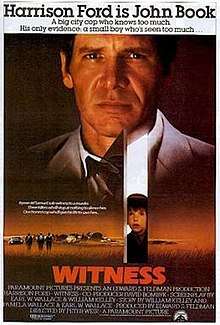

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Weir |

| Produced by | Edward S. Feldman |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Starring | Harrison Ford |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | Thom Noble |

Production company | Edward S. Feldman Productions |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language |

|

| Budget | $12 million |

| Box office | $68.7 million (US/Can)[1] |

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards and won two, for Best Original Screenplay and Best Film Editing. It was also nominated for seven BAFTA Awards, winning one for Maurice Jarre's score, and was also nominated for six Golden Globe Awards. William Kelley and Earl W. Wallace won the Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay and the 1986 Edgar Award for Best Motion Picture Screenplay presented by the Mystery Writers of America. Harrison Ford was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actor.

Plot

In 1984, an Amish community outside of Lancaster, Pennsylvania attends the funeral of Jacob Lapp, who leaves behind his young wife Rachel and eight-year-old son Samuel.

Rachel and Samuel travel by train to visit Rachel's sister, which takes them into Philadelphia. While waiting at 30th Street Station for a connecting train to Baltimore, Samuel goes into the men's room and witnesses the brutal murder of an undercover police officer, but manages to evade detection by hiding in the stalls.

Detective John Book (Harrison Ford) is assigned to the case where he and partner Sergeant Elton Carter question Samuel. Although Samuel is unable to identify the perpetrator from mug shots or a lineup, he later sees a newspaper clipping in a trophy case of narcotics officer James McFee receiving an award and points him out to Book. Book investigates and finds out that McFee was previously responsible for a seizure of expensive chemicals used to make black-market amphetamines, but the evidence has now disappeared. Book surmises that McFee himself fenced the chemicals to drug dealers, and that the murdered detective, Ian Zenovich, had been investigating the theft.

Book expresses his suspicions to Chief of Police Paul Schaeffer, who advises Book to keep the case secret so they can work out how to move forward. Book is later ambushed and shot in a parking garage by McFee and left badly wounded. Since only Schaeffer knew of Book's suspicions, Book realizes Schaeffer is also corrupt and tipped off McFee.

Realizing that Samuel and Rachel are now in grave danger, Book orders his partner to remove all traces of the Lapps from his files and drives the boy and his mother back home to Lancaster County where they could disappear within their community. While attempting to return to the city, Book's loss of blood causes him to pass out in front of their farm.

Book insists that going to a hospital would allow the corrupt police officers to find him and put Samuel in danger. Rachel's father-in-law Eli reluctantly agrees to shelter him despite his distrust of the outsider. Book slowly recovers in their care and begins to develop feelings for Rachel, who likewise is drawn to him. The Lapps' neighbor Daniel Hochleitner had hoped to court her and this becomes a cause of friction. During his convalescence, Book dresses in Jacob Lapp's clothing in order to avoid drawing attention to himself. His relationship with the Amish community deepens as they learn he is skilled at carpentry and seems like a decent, hard-working man.

Book is invited to participate in a barn raising for a newly married couple, gaining Hochleitner's respect. However, the attraction between Book and Rachel is evident and clearly concerns Eli and others, causing much gossip in the tight-knit community. That night Book inadvertently observes Rachel bathing, but as she stands half-naked before him, he walks away.

Book goes into town with Eli to use a payphone, where he learns that Carter has been killed. He deduces that Schaeffer and McFee murdered Carter after discovering his role in the case to get closer to Book, with the aid of a third corrupt officer, Detective Sergeant Leon "Fergie" Ferguson. While in town, Hochleitner is harassed by tourists. Book retaliates, breaking with the Amish tradition of non-violence. The fight between the bullies and the strange "Amish" man is reported to the local police, who then inform Schaeffer, having previously contacted the sheriff in his efforts to locate Book, Rachel and Samuel.

The next day, Schaeffer, McFee and Ferguson arrive at the Lapp farm, taking Rachel and Eli hostage as a way of luring Book and Samuel out. In hiding, Book orders Samuel to run to Hochleitner's home for safety, then tricks Ferguson into the corn silo and suffocates him under tons of corn. Upon arming himself with Ferguson's shotgun, Book kills McFee.

Samuel, hearing the gunshots, heads back to the farm. Schaeffer then forces Rachel and Eli out of the house at gunpoint; Eli signals to Samuel to ring the farm's bell. Book confronts Schaeffer, who threatens to kill Rachel, but the loud clanging from the bell summons the Amish, who resolutely gather near and silently watch him. With so many witnesses present, Schaeffer realizes he can't kill them all nor escape, and gives up; Book confiscates Schaeffer's weaponry before he is arrested.

Book says goodbye to Samuel in the fields as he prepares to leave; he and Rachel share a long loving gaze on the porch. Eli wishes him well "out there among them English" signifying his acceptance of Book as a member of their community. Book smiles and departs, exchanging a wave with Hochleitner on the road out.

Cast

- Harrison Ford as Det. John Book

- Kelly McGillis as Rachel Lapp

- Lukas Haas as Samuel Lapp

- Jan Rubeš as Eli Lapp

- Josef Sommer as Chief Paul Schaeffer

- Alexander Godunov as Daniel Hochleitner

- Danny Glover as Lt. James McFee

- Brent Jennings as Det. Sgt. Elton Carter

- Patti LuPone as Elaine

- Angus MacInnes as Det. Sgt. Leon “Fergie” Ferguson

- Viggo Mortensen as Moses Hochleitner

- Frederick Rolf as Stoltzfus

- John Garson as Bishop Tchantz

- Ed Crowley as Sheriff Krueger

- Timothy Carhart as Det. Ian Zenovich

- Beverly May as Mrs. Yoder

- Richard Chaves as Det. Sykes

- Robert Earl Jones as Harry

- Sylvia Kauders as Tourist

Production

Producer Edward S. Feldman, who was in a "first-look" development deal with 20th Century Fox at the time, first received the screenplay for Witness in 1983. Originally entitled Called Home (which is the Amish term for death), it ran 182 pages long, the equivalent of three hours of screen time. The script, which had been circulating in Hollywood for several years, had been inspired by an episode of Gunsmoke William Kelley and Earl W. Wallace had written in the 1970s.[3]

Feldman liked the concept, but felt too much of the script was devoted to Amish traditions, diluting the thriller aspects of the story. He offered Kelley and Wallace $25,000 for a one-year option and one rewrite, and an additional $225,000 if the film actually was made. They submitted the revised screenplay in less than six weeks, and Feldman delivered it to Fox. Joe Wizan, the studio's head of production, rejected it with the statement that Fox didn't make "rural movies".[3]

Feldman sent the screenplay to Harrison Ford's agent Phil Gersh, who contacted the producer four days later and advised him his client was willing to commit to the film. Certain the attachment of a major star would change Wizan's mind, Feldman approached him once again, but Wizan insisted that as much as the studio liked Ford, they still weren't interested in making a "rural movie."[3]

Feldman sent the screenplay to numerous studios and was rejected by all of them, until Paramount Pictures finally expressed interest. Feldman's first choice of director was Peter Weir, but he was involved in pre-production work for The Mosquito Coast and passed on the project. John Badham dismissed it as "just another cop movie", and others Feldman approached either were committed to other projects or had no interest. Then, as financial backing for The Mosquito Coast fell through, Weir became free to direct Witness, which was his first American film. It was imperative filming start immediately, because a Directors Guild of America strike was looming on the horizon.[3]

Casting

Lynne Littman had originally been in talks to direct the film, and even though she ultimately did not, she recommended Lukas Haas for the part of Samuel because she had recently worked with him on her film Testament. The role of Rachel was the most difficult to cast, and after Weir grew frustrated with the auditions he'd seen, he asked the casting director to look for actors in Italy because he thought they'd be more "womanly". As they were reviewing audition tapes from Italy, Kelly McGillis came in to audition, and the moment she put on the bonnet and said a few lines, Weir knew she was the one. The casting director recommended her old friend Alexander Godunov who had never acted before, but she thought his personality would be right, and Weir agreed. Viggo Mortensen was cast because Weir thought he had the right face for the part of an Amish man. Mortensen had just started his acting career, so this was his first film acting role, and he had to turn down another role as a soldier in Shakespeare in the Park's production of Henry V. He credited that decision and the very positive experience on the film as the start of his film career.[4]

Preproduction

During the weeks before filming, Ford spent time with the homicide department of the Philadelphia Police Department, researching the important details of working as a homicide detective. McGillis did research by moving in with an Amish widow and her seven children, learning how to milk cows and practicing their accents. Weir and cinematographer John Seale went on a trip to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where an exhibition of 17th century Dutch masters was going on. Weir pointed out the paintings of Johannes Vermeer, which were used as inspiration for the lighting and composition of the film, especially in the scenes where John Book is recovering in Rachel's house from a gunshot wound.[4]

Filming

The film was shot on location in Philadelphia and the city and towns of Intercourse, Lancaster, Strasburg and Parkesburg. Local Amish were willing to work as carpenters and electricians, but declined to appear on film, so many of the extras actually were Mennonites. Halfway through filming, the title was changed from Called Home to Witness at the behest of Paramount's marketing department, which felt the original title posed too much of a promotional challenge. Principal photography was completed three days before the scheduled DGA strike, which ultimately failed to materialize.[3]

During the setup and rehearsal of each scene as well as during dailies, Weir would play music to set the mood, with the idea that it prevented the actors from thinking too much and let them listen to their other instincts. The barn raising scene was only a short paragraph in the script, but Weir thought it was important to really highlight the aspect of community. They shot the scene in a day, and did in fact build a barn, albeit with the help of cranes off camera. To film the scene in the corn silo, corn was really dropped onto the actor, and scuba diving gear with an oxygen tank were hidden on the floor so that the actor would be able to breathe.[4]

Originally the script ended with a scene of Book and Rachel each explaining their feelings for each other to the audience, but Weir felt the scene was unnecessary and decided not to shoot it. The studio executives were worried that the audience wouldn't understand the ending and tried to convince him otherwise, but Weir insisted that the characters' emotions could be expressed with only visuals.[4]

Reception

Critical response

Witness was well received by critics and earned eight Academy Award nominations (including Weir's first and Ford's sole nomination to date). Witness currently holds a 93% "Fresh" rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on forty reviews. The site's consensus states: "A wonderfully entertaining thriller within an unusual setting, with Harrison Ford delivering a surprisingly emotive and sympathetic performance."[5]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times rated the film four out of four stars, calling it:

First of all, an electrifying and poignant love story. Then it is a movie about the choices we make in life and the choices that other people make for us. Only then is it a thriller—one that Alfred Hitchcock would have been proud to make... We have lately been getting so many pallid, bloodless little movies—mostly recycled teenage exploitation films made by ambitious young stylists without a thought in their heads—that Witness arrives like a fresh new day. It is a movie about adults, whose lives have dignity and whose choices matter to them. And it is also one hell of a thriller.[6]

Ebert also praised Ford's work and claimed he had "never given a better performance in a movie." Vincent Canby of The New York Times:

It's not really awful, but it's not much fun. It's pretty to look at and it contains a number of good performances, but there is something exhausting about its neat balancing of opposing manners and values... One might be made to care about all this if the direction by the talented Australian film maker, Peter Weir... were less perfunctory and if the screenplay... did not seem so strangely familiar. One follows Witness as if touring one's old hometown, guided by an outsider who refuses to believe that one knows the territory better than he does. There's not a character, an event or a plot twist that one hasn't anticipated long before its arrival, which gives one the feeling of waiting around for people who are always late.[7]

Variety said the film was "at times a gentle, affecting story of star-crossed lovers limited within the fascinating Amish community. Too often, however, this fragile romance is crushed by a thoroughly absurd shoot-em-up, like ketchup poured over a delicate Pennsylvania Dutch dinner."[8]

Time Out New York observed, "Powerful, assured, full of beautiful imagery and thankfully devoid of easy moralising, it also offers a performance of surprising skill and sensitivity from Ford."[9]

Halliwell's Film Guide chose Witness as one of only two films from 1985 to receive a four star review, describing it as "one of those lucky movies which works out well on all counts and shows that there are still craftsmen lurking in Hollywood."[10]

Radio Times called the film "partly a love story and partly a thriller, but mainly a study of cultural collision – it's as if the world of Dirty Harry had suddenly stumbled into a canvas by Brueghel." It added, "[I]t's Weir's delicacy of touch that impresses the most. He ably juggles the various elements of the story and makes the violence seem even more shocking when it's played out on the fields of Amish denial."[11]

The film was screened out of competition at the 1985 Cannes Film Festival.[12]

Box office

The film opened in 876 theaters in the United States on February 8, 1985 and grossed $4,539,990 in its opening weekend, ranking No. 2 behind Beverly Hills Cop. It remained at No. 2 for the next three weeks and finally topped the charts in its fifth week of release. It eventually earned $68,706,993 in the United States.[1]

Legacy

Negotiation expert William Ury summarized the film's climactic scene in a chapter titled "The Witness" in his 1999 book Getting to Peace (later republished with the alternate title The Third Side: Why We Fight and How We Can Stop) and used the scene as a symbol of the power of ordinary citizens to resolve conflicts and stop violence.[13]

This scene from the popular movie Witness captures the power of ordinary community members to contain violence. The Amish farmers were present as the third side in perhaps its most elemental form, seemingly doing nothing, but in fact playing the critical role of Witness. Like the Amish, we are all potential Witnesses.

Awards and nominations

| Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Picture | Edward S. Feldman | Nominated |

| Best Director | Peter Weir | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Earl W. Wallace, William Kelley and Pamela Wallace | Won | |

| Best Actor | Harrison Ford | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Maurice Jarre | Nominated | |

| Best Cinematography | John Seale | Nominated | |

| Best Art Direction | Stan Jolley and John H. Anderson | Nominated | |

| Best Film Editing | Thom Noble | Won | |

| BAFTA Awards | Best Film | Nominated | |

| Best Original Screenplay | Earl W. Wallace, William Kelley and Pamela Wallace | Nominated | |

| Best Actor | Harrison Ford | Nominated | |

| Best Actress | Kelly McGillis | Nominated | |

| Best Music | Maurice Jarre | Won | |

| Best Cinematography | John Seale | Nominated | |

| Best Editing | Thom Noble | Nominated | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Motion Picture – Drama | Nominated | |

| Best Director | Peter Weir | Nominated | |

| Best Screenplay | Earl W. Wallace, William Kelley and Pamela Wallace | Nominated | |

| Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama | Harrison Ford | Nominated | |

| Best Supporting Actress | Kelly McGillis | Nominated | |

| Best Original Score | Maurice Jarre | Nominated | |

| Kansas City Film Critics Circle | Best Film | Won | |

| Best Actor | Harrison Ford | Won | |

| Writers Guild of America | Best Original Screenplay | Earl W. Wallace, William Kelley and Pamela Wallace | Won |

| Directors Guild of America | Outstanding Directing | Peter Weir | Nominated |

| Grammy Awards | Best Score | Maurice Jarre | Nominated |

| American Cinema Editors | Best Edited Feature Film | Thom Noble | Won |

| Australian Cinematographers Society | Cinematographer of the Year | John Seale | Won |

| British Society of Cinematographers | Best Cinematography | Nominated |

Controversy

The film was not well-received by the Amish communities where it was filmed.[14] A statement released by a law firm associated with the Amish claimed that their portrayal in the movie was not accurate. The National Committee For Amish Religious Freedom called for a boycott of the movie soon after its release, citing fears that these communities were being "overrun by tourists" as a result of the popularity of the movie, and worried that "the crowding, souvenir-hunting, photographing and trespassing on Amish farmsteads will increase." After the movie was completed, Pennsylvania governor Dick Thornburgh agreed not to promote Amish communities as future film sites. A similar concern was voiced within the movie itself, where Rachel tells a recovering Book that tourists often consider her fellow Amish something to stare at, with some even being so rude as to trespass on their private property.[15]

References

- "Witness". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com.

- Silver, Alain; Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.). Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press. ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- Feldman, Edward S. (2005). Tell Me How You Love the Picture. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 180–190. ISBN 0-312-34801-0.

- Keith Clark and Jon Mefford (2005). "Between Two Worlds: The Making of Witness". Witness (DVD). Paramount Pictures. OCLC 949729643.

- https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/1023854-witness

- Ebert, Roger (February 8, 1985). "Witness". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- Canby, Vincent (February 8, 1985). "FILM: 'WITNESS,' A TOUGH GUY AMONG THE AMISH". Retrieved June 30, 2018.

- "Witness". Variety. December 31, 1984.

- "Witness Review". Time Out New York. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013.

- Halliwell's Film Guide, 13th edition – ISBN 0-00-638868-X.

- John Ferguson. "Witness review". Radio Times.

- "Festival de Cannes: Witness". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Ury, William (2000) [1999]. The third side: why we fight and how we can stop (Revised ed.). New York: Penguin Books. pp. 170–171. ISBN 0140296344. OCLC 45610553.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hostetler, John A.; Kraybill, Donald B. (1988). "Hollywood markets the Amish". In Gross, Larry P.; Katz, John Stuart; Ruby, Jay (eds.). Image ethics: the moral rights of subjects in photographs, film, and television. Communication and society. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 220–235. ISBN 0195054334. OCLC 17676506.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Amish ask boycott of movie 'Witness'". Pittsburgh Press. February 16, 1985. Retrieved January 4, 2013.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Witness (1985 film) |

- Witness on IMDb

- Witness at the TCM Movie Database

- Witness at Box Office Mojo

- Witness at Rotten Tomatoes