Laurel forest

Laurel forest, also called laurisilva or laurissilva, is a type of subtropical forest found in areas with high humidity and relatively stable, mild temperatures. The forest is characterized by broadleaf tree species with evergreen, glossy and elongated leaves, known as "laurophyll" or "lauroid". Plants from the laurel family (Lauraceae) may or may not be present, depending on the location.

.jpg)

Setting

Laurel forests are specific to wet forests from sea level to the highest mountains, but are poorly represented in areas with a pronounced dry season. They need an ecosystem of high humidity, such as cloud forests, with abundant rainfall throughout the year. Laurel forests typically occur on the slopes of tropical or subtropical mountains, where the moisture from the ocean condenses so that it falls as rain or fog and soils have high moisture levels.[1] Some evergreen tree species will survive short frosts, but most species will not survive hard freezes and prolonged cool weather. They need a mild climate with annual temperature oscillation moderated by the proximity of the ocean. These conditions of temperature and moisture occur in four different geographical regions:

- Along the eastern margin of continents at latitudes of 25° to 35°.

- Along the western continental coasts between 35° and 50° latitude.

- On islands between 25° and 35° or 40° latitude.

- In humid montane regions of the tropics.[2][3][4]

Some laurel forests are a type of cloud forest. Cloud forests are found on mountain slopes where the dense moisture from the sea or ocean is precipitated as warm moist air masses blowing off the ocean are forced upwards by the terrain, which cools the air mass to the dew point. The moisture in the air condenses as rain or fog, creating a habitat characterized by cool, moist conditions in the air and soil. The resulting climate is wet and mild, with the annual oscillation of the temperature moderated by the proximity of the ocean.

Characteristics

Laurel forests are characterized by evergreen and hardwood trees, reaching up to 40 metres (130 ft) in height. Laurel forest, laurisilva, and laurissilva all refer to plant communities that resemble the bay laurel.

Some species belong to the true laurel family, Lauraceae, but many have similar foliage to the Lauraceae due to convergent evolution. As in any other rainforest, plants of the laurel forests must adapt to high rainfall and humidity. The trees have adapted in response to these ecological drivers by developing analogous structures, leaves that repel water. Laurophyll or lauroid leaves are characterized by a generous layer of wax, making them glossy in appearance, and a narrow, pointed oval shape with an apical mucro or "drip tip", which permits the leaves to shed water despite the humidity, allowing respiration. The scientific names laurina, laurifolia, laurophylla, lauriformis, and lauroides are often used to name species of other plant families that resemble the Lauraceae.[5] The term Lucidophyll, referring to the shiny surface of the leaves, was proposed in 1969 by Tatuo Kira.[6] The scientific names Daphnidium, Daphniphyllum, Daphnopsis, Daphnandra, Daphne[7] from Greek: Δάφνη, meaning "laurel", laurus, Laureliopsis, laureola, laurelin, laurifolia, laurifolius, lauriformis, laurina, , Prunus laurocerasus (English laurel), Prunus lusitanica (Portugal laurel), Corynocarpus laevigatus (New Zealand Laurel), and Corynocarpus rupestris designate species of other plant families whose leaves resemble Lauraceae.[5] The term "lauroid" is also applied to climbing plants such as ivies, whose waxy leaves somewhat resemble those of the Lauraceae.

Mature laurel forests typically have a dense tree canopy and low light levels at the forest floor.[6] Some forests are characterized by an overstory of emergent trees.

Laurel forests are typically multi-species, and diverse in both the number of species and the genera and families represented.[6] In the absence of strong environmental selective pressure, the number of species sharing the arboreal stratum is high, although not reaching the diversity of tropical forests; nearly 100 tree species have been described in the laurisilva rainforest of Misiones (Argentina), about 20 in the Canary Islands. This species diversity contrasts with other temperate forest types, which typically have a canopy dominated by one or a few species. Species diversity generally increases towards the tropics.[8] In this sense, the laurel forest is a transitional type between temperate forests and tropical rainforests.

Origin

Laurel forests are composed of vascular plants that evolved millions of years ago. Lauroid floras have included forests of Podocarpaceae and southern beech.

This type of vegetation characterized parts of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwana and once covered much of the tropics. Some lauroid species that are found outside laurel forests are relicts of vegetation that covered much of the mainland of Australia, Europe, South America, Antarctica, Africa, and North America when their climate was warmer and more humid. Cloud forests are believed to have retreated and advanced during successive geological eras, and their species adapted to warm and wet conditions were replaced by more cold-tolerant or drought-tolerant sclerophyll plant communities. Many of the late Cretaceous – early Tertiary Gondwanan species of flora became extinct, but some survived as relict species in the milder, moister climate of coastal areas and on islands.[9] Thus Tasmania and New Caledonia share related species extinct on the Australian mainland, and the same case occurs on the Macaronesia islands of the Atlantic and on the Taiwan, Hainan, Jeju, Shikoku, Kyūshū, and Ryūkyū Islands of the Pacific.

Although some remnants of archaic flora, including species and genera extinct in the rest of the world, have persisted as endemic to such coastal mountain and shelter sites, their biodiversity was reduced. Isolation in these fragmented habitats, particularly on islands, has led to the development of vicariant species and genera. Thus, fossils dating from before the Pleistocene glaciations show that species of Laurus were formerly distributed more widely around the Mediterranean and North Africa. Isolation gave rise to Laurus azorica in the Azores Islands, Laurus nobilis on the mainland, and Laurus novocanariensis in the Madeira and the Canary Islands.

Laurel forest ecoregions

Laurel forests occur in small areas where their particular climatic requirements prevail, in both the northern and southern hemispheres. Inner laurel forest ecoregions, a related and distinct community of vascular plants, evolved millions of years ago on the supercontinent of Gondwana, and species of this community are now found in several separate areas of the Southern Hemisphere, including southern South America, southernmost Africa, New Zealand, Australia and New Caledonia. Most Laurel forest species are evergreen, and occur in tropical, subtropical, and mild temperate regions and cloud forests of the northern and southern hemispheres, in particular the Macaronesian islands, southern Japan, Madagascar, New Caledonia, Tasmania, and central Chile, but they are pantropical, and for example in Africa they are endemic to the Congo region, Cameroon, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda, in lowland forest and Afromontane areas. Since laurel forests are archaic populations that diversified as a result of isolation on islands and tropical mountains, their presence is a key to dating climatic history.

East Asia

Laurel forests are common in subtropical eastern Asia, and form the climax vegetation in far southern Japan, Taiwan, southern China, the mountains of Indochina, and the eastern Himalayas. In southern China, laurel forest once extended throughout the Yangtze Valley and Sichuan Basin from the East China Sea to the Tibetan Plateau. The northernmost laurel forests in East Asia occur at 39° N. on the Pacific coast of Japan. Altitudinally, the forests range from sea-level up to 1000 metres in warm-temperate Japan, and up to 3000 metres elevation in the subtropical mountains of Asia.[8] Some forests are dominated by Lauraceae, while in others evergreen laurophyll trees of the beech family (Fagaceae) are predominant, including ring-cupped oaks (Quercus subgenus Cyclobalanopsis), chinquapin (Castanopsis) and tanoak (Lithocarpus).[6] Other characteristic plants include Schima and Camellia, which are members of the tea family (Theaceae), as well as magnolias, bamboo, and rhododendrons.[10] These subtropical forests lie between the temperate deciduous and conifer forests to the north and the subtropical/tropical monsoon forests of Indochina and India to the south.

Associations of Lauraceous species are common in broadleaved forests; for example, Litsea spp., Persea odoratissima, Persea duthiei, etc., along with such others as Engelhardia spicata, tree rhododendron (Rhododendron arboreum), Lyonia ovalifolia, wild Himalayan pear (Pyrus pashia), sumac (Rhus spp.), Himalayan maple (Acer oblongum), box myrtle (Myrica esculenta), magnolia (Michelia spp.), and birch (Betula spp.). Some other common trees and large shrub species of subtropical forests are Semecarpus anacardium, Crateva unilocularis, Trewia nudiflora, Premna interrupta, vietnam elm (Ulmus lancifolia), Ulmus chumlia, Glochidion velutinum, beautyberry (Callicarpa arborea), Indian mahogany (Toona ciliata), fig tree (Ficus spp.), Mahosama similicifolia, Trevesia palmata, brushholly (Xylosma longifolium), false nettle (Boehmeria rugulosa), Schefflera venulosa, Casearia graveilens, Actinodaphne reticulata, Sapium insigne, Nepalese alder (Alnus nepalensis), marlberry (Ardisia thyrsiflora), holly (Ilex spp), Macaranga pustulata, Trichilia cannoroides, hackberry (Celtis tetranda), Wenlendia puberula, Saurauia nepalensis, ring-cupped oak (Quercus glauca), Ziziphus incurva, Camellia kissi, Hymenodictyon flaccidum, Maytenus thomsonii, winged prickly ash (Zanthoxylum armatum), Eurya acuminata, matipo (Myrsine semiserrata), Sloanea tomentosa, Hydrangea aspera, Symplocos spp., and Cleyera spp.

In the temperate zone, the cloud forest between 2,000 and 3,000 m altitude supports broadleaved evergreen forest dominated by plants such as Quercus lamellosa and Q. semecarpifolia in pure or mixed stands. Lindera and Litsea species, Himalayan hemlock (Tsuga dumosa), and Rhododendron spp. are also present in the upper levels of this zone. Other important species are Magnolia campbellii, Michelia doltsopa, andromeda (Pieris ovalifolia), Daphniphyllum himalense, Acer campbellii, Acer pectinatum, and Sorbus cuspidata, but these species do not extend toward the west beyond central Nepal. Nepalese alder (Alnus nepalensis), a pioneer tree species, grows gregariously and forms pure patches of forests on newly exposed slopes, in gullies, beside rivers, and in other moist places.

The common forest types of this zone include Rhododendron arboreum, Rhododendron barbatum, Lyonia spp., Pieris formosa; Tsuga dumosa forest with such deciduous taxa as maple (Acer) and Magnolia; deciduous mixed broadleaved forest of Acer campbellii, Acer pectinatum, Sorbus cuspidata, and Magnolia campbellii; mixed broadleaved forest of Rhododendron arboreum, Acer campbellii, Symplocos ramosissima and Lauraceae.

This zone is habitat for many other important tree and large shrub species such as pindrow fir (Abies pindrow), East Himalayan fir (Abies spectabilis), Acer campbellii, Acer pectinatum, Himalayan birch (Betula utilis), Betula alnoides, boxwood (Buxus rugulosa), Himalayan flowering dogwood (Cornus capitata), hazel (Corylus ferox), Deutzia staminea, spindle (Euonymus tingens), Siberian ginseng (Acanthopanax cissifolius), Coriaria terminalis, ash (Fraxinus macrantha), Dodecadenia grandiflora, Eurya cerasifolia, Hydrangea heteromala, Ilex dipyrena, privet (Ligustrum spp.), Litsea elongata, common walnut (Juglans regia), Lichelia doltsopa, Myrsine capitallata, Neolitsea umbrosa, mock-orange (Philadelphus tomentosus), sweet olive (Osmanthus fragrans), Himalayan bird cherry (Prunus cornuta), and Viburnum continifolium.

In ancient times, laurel forests (shoyojurin) were the predominant vegetation type in the Taiheiyo evergreen forests ecoregion of Japan, which encompasses the mild temperate climate region of southeastern Japan's Pacific coast. There were three main types of evergreen broadleaf forests, in which Castanopsis, Machilus, or Quercus predominated. Most of these forests were logged or cleared for cultivation and replanted with faster-growing conifers, like pine or hinoki, and only a few pockets remain.[11]

Laurel forest ecoregions in East Asia

- Changjiang Plain evergreen forests (China)

- Chin Hills-Arakan Yoma montane rain forests (Myanmar)

- Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests (Bhutan, India, Nepal)

- Guizhou Plateau broadleaf and mixed forests (China)

- Nihonkai evergreen forests (Japan)

- Northern Annamites rain forests (Laos, Vietnam)

- Northern Indochina subtropical forests (China, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand, Vietnam)

- Northern Triangle subtropical forests (Myanmar)

- South China-Vietnam subtropical evergreen forests (China, Vietnam)

- Southern Korea evergreen forests (South Korea)

- Taiheiyo evergreen forests (Japan)

- Taiwan subtropical evergreen forests (Taiwan)

Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines

Laurel forests occupy the humid tropical highlands of the Malay Peninsula, Greater Sunda Islands, and Philippines above 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) elevation. The flora of these forests is similar to that of the warm-temperate and subtropical laurel forests of East Asia, including oaks (Quercus), tanoak (Lithocarpus), chinquapin (Castanopsis), Lauraceae, Theaceae, and Clethraceae.

Epiphytes, including orchids, ferns, moss, lichen, and liverworts, are more abundant than in either temperate laurel forests or the adjacent lowland tropical rain forests. Myrtaceae are common at lower elevations, and conifers and rhododendrons at higher elevations. These forests are distinct in species composition from the lowland tropical forests, which are dominated by Dipterocarps and other tropical species.[12]

Laurel forest ecoregions of Sundaland, Wallacea, and the Philippines

- Borneo montane rain forests

- Eastern Java-Bali montane rain forests

- Luzon montane rain forests

- Mindanao montane rain forests

- Peninsular Malaysian montane rain forests

- Sulawesi montane rain forests

- Sumatran montane rain forests

- Western Java montane rain forests

Macaronesia and the Mediterranean Basin

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Old roads and passages between villages and other places in Madeira Island surrounded by prehistoric forest | |

| Location | Island of Madeira, Madeira, Portugal |

| Criteria | Natural: (ix)(x) |

| Reference | 934 |

| Inscription | 1999 (23rd session) |

| Area | 15,000 ha (58 sq mi) |

| Coordinates | 32°46′N 17°0′W |

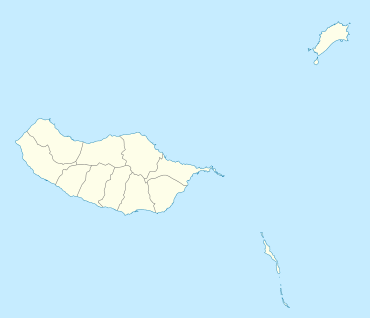

Location of Laurisilva of Madeira  Laurel forest (Africa) | |

Laurel forests are found in the islands of Macaronesia in the eastern Atlantic, in particular the Azores, Madeira Islands, and Canary Islands from 400 to 1200 metres elevation. Trees of the genera Apollonias (Lauraceae), Ocotea (Lauraceae), Persea (Lauraceae), Clethra (Clethraceae), Dracaena (Ruscaceae), and Picconia (Oleaceae) are characteristic.[13] The Garajonay National Park, on the island of La Gomera, was designated a World Heritage site by UNESCO in 1986. It is considered the best example of laurisilva rain forest in Europe, due to its great biodiversity and good preservation. The paleobotanical record of La Gomera reveals that laurisilva rain forests have existed on this island for at least 1.8 million years.[14]

Millions of years ago, laurel forests were widespread around the Mediterranean Basin. The drying of the region since the Pliocene and cooling during the ice ages caused these rainforests to retreat. Some relict Mediterranean laurel forest species, such as sweet bay (Laurus nobilis) and European holly (Ilex aquifolium), are fairly widespread around the Mediterranean basin.

In the Mediterranean there are other areas with species adapted to the same habitat, but which generally do not form a laurel forest, except very locally in the southernmost tip of the Iberian Peninsula.[15] The most important is ivy, a climber or vine that is well represented in most of Europe, where it spread again after the glaciations. The "loro" (Prunus lusitanica) is the only tree that survives as a relict in some Iberian riversides, especially in the western part of the peninsula, particularly the Extremadura, and to a small extent in the northeast. In other cases, the presence of Mediterranean laurel (Laurus nobilis) provides an indication of the previous existence of laurel forest. This species survives natively in Morocco, Italy, Portugal, Greece, the Mediterranean islands, and some areas of Spain, including the Parque Natural Los Alcornocales in the province of Cádiz and in coastal mountains, especially in the Girona Province, and isolated in the Valencia area. The myrtle spread through North Africa. Tree Heath (Erica arborea) grows in southern Iberia, but without reaching the dimensions observed in the temperate evergreen forest or North Africa. The broad-leaved Rhododendron ponticum baeticum and/or Rhamnus frangula baetica still persist in humid microclimates, such as stream valleys, in Cádiz (Spain), in the Portuguese Serra de Monchique, and the Rif Mountains of Morocco.[16]

Although the Atlantic laurisilva is more abundant in the Macaronesian archipelagos, where the weather has fluctuated little since the Tertiary, there are small representations and some species contribution to the oceanic and Mediterranean ecoregions of Europe, Asia minor and west and north of Africa, where microclimates in the coastal mountain ranges form inland "islands" favorable to the persistence of laurel forests. In some cases these were genuine islands in the Tertiary, and in some cases simply areas that remained ice-free. When the Strait of Gibraltar reclosed, the species repopulated toward the Iberian Peninsula to the north and were distributed along with other African species, but the seasonally drier and colder climate, prevented them reaching their previous extent. In Atlantic Europe, subtropical vegetation is interspersed with taxa from Europe and North Africa in bioclimatic enclaves such as the Serra de Monchique, Sintra, and the coastal mountains from Cadiz to Algeciras. In the Mediterranean region, remnant laurel forest is present on some islands of the Aegean Sea, on the Black Sea coast of Iran and Turkey, including the Castanopsis and true laurus forests, associated with Prunus laurocerasus, and conifers such as Taxus baccata, Cedrus atlantica, and Abies pinsapo.

In Europe the laurel forest has been badly damaged by timber harvesting, by fire (both accidental and deliberate to open fields for crops), by the introduction of exotic animal and plant species that have displaced the original cover, and by replacement with arable fields, exotic timber plantations, cattle pastures, and golf courses and tourist facilities. Most of the biota is in serious danger of extinction. The laurel forest flora is usually strong and vigorous and the forest regenerates easily; its decline is due to external forces.

Laurel forest ecoregions of Macaronesia

Nepal

In the Himalayas, in Nepal, subtropical forest consists of species such as Schima wallichii, Castanopsis indica, and Castanopsis tribuloides in relatively humid areas. Some common forest types in this region include Castanopsis tribuloides mixed with Schima wallichi, Rhododendron spp., Lyonia ovalifolia, Eurya acuminata, and Quercus glauca; Castanopsis-Laurales forest with Symplocas spp.; Alnus nepalensis forests; Schima wallichii-Castanopsis indica hygrophile forest; Schima-Pinus forest; Pinus roxburghii forests with Phyllanthus emblica. Semicarpus anacardium, Rhododendron arboreum and Lyoma ovalifolia; Schima-Lagestromea parviflora forest, Quercus lamellosa forest with Quercus lanata and 'Quercus glauca; Castanopsis forests with Castanopsis hystrix and Lauraceae.

Southern India

Laurel forests are also prevalent in the montane rain forests of the Western Ghats in southern India.

Sri Lanka

Laurel forest occurs in the montane rain forest of Sri Lanka.

Africa

The Afromontane laurel forests describe the plant and animal species common to the mountains of Africa and the southern Arabian Peninsula. The afromontane regions of Africa are discontinuous, separated from each other by lowlands, resembling a series of islands in distribution. Patches of forest with Afromontane floristic affinities occur all along the mountain chains. Afromontane communities occur above 1,500–2,000 metres (4,900–6,600 ft) elevation near the equator, and as low as 300 metres (980 ft) elevation in the Knysna-Amatole montane forests of South Africa. Afromontane forests are cool and humid. Rainfall is generally greater than 700 millimetres per year (28 in/year), and can exceed 2,000 millimetres (79 in) in some regions, occurring throughout the year or during winter or summer, depending on the region. Temperatures can be extreme at some of the higher altitudes, where snowfalls may occasionally occur.

In Subsaharan Africa, laurel forests are found in the Cameroon Highlands forests along the border of Nigeria and Cameroon, along the East African Highlands, a long chain of mountains extending from the Ethiopian Highlands around the African Great Lakes to South Africa, in the Highlands of Madagascar, and in the montane zone of the São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón moist lowland forests. These scattered highland laurophyll forests of Africa are similar to one another in species composition (known as the Afromontane flora), and distinct from the flora of the surrounding lowlands.

The main species of the Afromontane forests include the broadleaf canopy trees of genus Beilschmiedia, with Apodytes dimidiata, Ilex mitis, Nuxia congesta, N. floribunda, Kiggelaria africana, Prunus africana, Rapanea melanophloeos, Halleria lucida, Ocotea bullata, and Xymalos monospora, along with the emergent conifers Podocarpus latifolius and Afrocarpus falcatus. Species composition of the Subsaharan laurel forests differs from that of Eurasia. Trees of the Laurel family are less prominent, limited to Ocotea or Beilschmiedia due to exceptional biological and paleoecological interest and the enormous biodiversity mostly but with many endemic species, and the members of the beech family (Fagaceae) are absent.[8]

Trees can be up to 30 or 40 metres (98 or 131 ft) tall and distinct strata of emergent trees, canopy trees, and shrub and herb layers are present. Tree species include: Real Yellowwood (Podocarpus latifolius), Outeniqua Yellowwood (Podocarpus falcatus), White Witchhazel (Trichocladus ellipticus), Rhus chirendensis, Curtisia dentata, Calodendrum capense, Apodytes dimidiata, Halleria lucida, llex mitis, Kiggelaria africana, Nuxia floribunda, Xymalos monospora, and Ocotea bullata. Shrubs and climbers are common and include: Common Spikethorn (Maytenus heterophylla), Cat-thorn (Scutia myrtina), Numnum (Carissa bispinosa), Secamone alpinii, Canthium ciliatum, Rhoicissus tridentata, Zanthoxylum capense, and Burchellia bubalina. In the undergrowth grasses, herbs and ferns may be locally common: Basketgrass (Oplismenus hirtellus), Bushman Grass (Stipa dregeana var. elongata), Pigs-ears (Centella asiatica), Cyperus albostriatus, Polypodium polypodioides, Polystichum tuctuosum, Streptocarpus rexii, and Plectranthus spp. Ferns, shrubs and small trees such as Cape Beech (Rapanea melanophloeos) are often abundant along the forest edges.

USA Southeast States

According to the recent study by Box and Fujiwara (Evergreen Broadleaved Forests of the Southeastern United States: Preliminary Description), laurel forests occur in patches in the southeastern United States from southeast Virginia southward to Florida, and west to Texas, mostly along the coast and coastal plain of the Gulf and south Atlantic coast. In the southeastern United States, evergreen Hammock (ecology) (i.e. topographically induced forest islands) contain many laurel forests. These laurel forests occur mostly in moist depression and floodplains, and are found in moist environments of the Mississippi river basin to southern Illinois. In many portions of the coastal plain, a low-lying mosaic topography of white sand, silt, and limestone (mostly in Florida), separate these laurel forests. Frequent fire is also thought to be responsible for the disjointed geography of laurel forests across the coastal plain of the southeastern United States.

Despite being located in a humid climate zone, much of the broadleaf Laurel forests in the Southeast USA are semi-sclerophyll in character. The semi-sclerophyll character is due (in part) to the sandy soils and often periodic semi-arid nature of the climate. As one moves south into central Florida, as well as far southern Texas and the Gulf Coastal margin of the southern United States, the sclerophyll character slowly declines and more tree species from the tropics (specifically, the Caribbean and Mesoamerica) increase as the temperate species decline. As such, the southeastern laurel forests gives way to a mixed landscape of tropical savanna and tropical rainforest.

There are several different broadleaved evergreen canopy trees in the laurel forests of the southeastern United States. In some areas, the evergreen forests are dominated by species of Live Oak (Quercus virginiana), Laurel Oak (Quercus hemisphaerica), Southern Magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora), Red Bay (Persea borbonia), Cabbage Palm (Sabal palmetto), and Sweetbay Magnolia (Magnolia virginiana). In several areas on the barrier islands, a stunted Quercus geminata or mixed Quercus geminata and Quercus virginiana forest dominates, with a dense evergreen understory of scrub palm Serenoa repens and a variety of vines, including Bignonia capreolata, as well as Smilax and Vitis species'. Gordonia lasianthus, Ilex opaca and Osmanthus americanus also may occur as canopy co-dominant in coastal dune forests, with Cliftonia monophylla and Vaccinium arboreum as a dense evergreen understory (Box and Fujiwara 1988).

The lower shrub layer of the evergreen forests is often mixed with other evergreen species from the palm family (Rhapidophyllum hystrix), Bush palmetto(Sabal minor), and Saw Palmetto (Serenoa repens), and several species in the Ilex family, including Ilex glabra, Dahoon Holly, and Yaupon Holly. In many areas, Cyrilla racemiflora, Lyonia fruticosa, Wax Myrtle Myrica is present as an evergreen understory. Several species of Yucca and Opuntia are native as well to the drier sandy coastal scrub environment of the region, including Yucca aloifolia, Yucca filamentosa, Yucca gloriosa, and opuntia stricta.

USA ancient California

During the Miocene, oak-laurel forests were found in Central and Southern California. Typical tree species included oaks ancestral to present-day California oaks, as well as an assemblage of trees from the Laurel family, including Nectandra, Ocotea, Persea, and Umbellularia.[17][18] Only one native species from the Laurel family (Lauraceae), Umbellularia californica, remains in California today.

There are however, several areas in Mediterranean California, as well as isolated areas of southern Oregon that have evergreen forests. Several species of evergreen Quercus forests occur, as well as a mix of evergreen scrub typical of Mediterranean climates. Species of Notholithocarpus, Arbutus menziesii, and Umbellularia californica can be canopy species in several areas.

Central America

The laurel forest is the most common Central American temperate evergreen cloud forest type. They are found in mountainous areas of southern Mexico and almost all Central American countries, normally more than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) above sea level. Tree species include evergreen oaks, members of the Laurel family, and species of Weinmannia, Drimys, and Magnolia.[19] The cloud forest of Sierra de las Minas, Guatemala, is the largest in Central America. In some areas of southeastern Honduras there are cloud forests, the largest located near the border with Nicaragua. In Nicaragua the cloud forests are found in the border zone with Honduras, and most were cleared to grow coffee. There are still some temperate evergreen hills in the north. The only cloud forest in the Pacific coastal zone of Central America is on the Mombacho volcano in Nicaragua. In Costa Rica there are laurisilvas in the "Cordillera de Tilarán" and Volcán Arenal, called Monteverde, also in the Cordillera de Talamanca.

Laurel forest ecoregions in Mexico and Central America

- Central American montane forests

- Chiapas montane forests

- Chimalpas montane forests

- Oaxacan montane forests

- Talamancan montane forests

- Veracruz montane forests

Tropical Andes

The Yungas are typically evergreen forests or jungles, and multi-species, which often contain many species of the laurel forest. They occur discontinuously from Venezuela to northwestern Argentina including in Brazil, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, and Peru, usually in the Sub-Andean Sierras. The forest relief is varied and in places where the Andes meet the Amazon, it includes steeply sloped areas. Characteristic of this region are deep ravines formed by the rivers, such as that of the Tarma River descending to the San Ramon Valley, or the Urubamba River as it passes through Machu Picchu. Many of the Yungas are degraded or are forests in recovery that have not yet reached their climax vegetation.

Southeastern South America

The laurel forests of the region are known as the Laurisilva Misionera, after Argentina's Misiones Province. The Araucaria moist forests occupy a portion of the highlands of southern Brazil, extending into northeastern Argentina. The forest canopy includes species of Lauraceae (Ocotea pretiosa and O. catharinense), Myrtaceae (Campomanesia xanthocarpa), and Leguminosae (Parapiptadenia rigida), with an emergent layer of the conifer Brazilian Araucaria (Araucaria angustifolia) reaching up to 45 metres (148 ft) in height.[20] The subtropical Serra do Mar coastal forests along the southern coast of Brazil have a tree canopy of Lauraceae and Myrtaceae, with emergent trees of Leguminaceae, and a rich diversity of bromeliads and trees and shrubs of family Melastomaceae.[21] The inland Alto Paraná Atlantic forests, which occupy portions of the Brazilian Highlands in southern Brazil and adjacent parts of Argentina and Paraguay, are semi-deciduous.

Central Chile

The Valdivian temperate rain forests, or Laurisilva Valdiviana, occupy southern Chile and Argentina from the Pacific Ocean to the Andes between 38° and 45° latitude. Rainfall is abundant, from 1,500 to 5,000 millimetres (59–197 in) according to locality, distributed throughout the year, but with some subhumid Mediterranean climate influence for 3–4 months in summer. The temperatures are sufficiently invariant and mild, with no month falling below 5 °C (41 °F), and the warmest month below 22 °C (72 °F).

Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand

Laurel forest appears on mountains of the coastal strip of New South Wales in Australia, New Guinea, New Caledonia, Tasmania, and New Zealand. The laurel forests of Australia, Tasmania, and New Zealand are home to species related to those in the Valdivian laurel forests, including Southern Beech (Nothofagus, fossils of which have recently been found in Antarctica[22]) through the connection of the Antarctic flora. Other typical flora include Winteraceae, Myrtaceae, Southern Sassafras (Atherospermataceae), conifers of Araucariaceae, Podocarpaceae, and Cupressaceae, and tree ferns.[23]

New Caledonia was an ancient fragment of the supercontinent Gondwana. Unlike many of the Pacific Islands, which are of relatively recent volcanic origin, New Caledonia is part of Zealandia, a fragment of the ancient Gondwana that separated from Australia 60–85 million years ago,[24] and the ridge linking New Caledonia to New Zealand has been deeply submerged for millions of years. This isolated New Caledonia from the rest of the world's landmasses, preserving a snapshot of Gondwanan forests. New Caledonia and New Zealand are separated by continental drift of Australia 85 million years ago. The islands still shelter an extraordinary diversity of endemic plants and animals of Gondwanan origin that have later spread to the southern continents.

The laurel forest of Australia, New Caledonia (Adenodaphne), and New Zealand have a number of species related to those of the Valdivian laurel forest, through the connection of the Antarctic flora of gymnosperms like the podocarpus and deciduous Nothofagus. Beilschmiedia tawa is often the dominant canopy species of genus Beilschmiedia in lowland laurel forests in the North Island and the northeast of the South Island, but will also often form the subcanopy in primary forests throughout the country in these areas, with podocarps such as Kahikatea, Matai, Miro and Rimu. Genus Beilschmiedia are trees and shrubs widespread in tropical Asia, Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Central America, the Caribbean, and South America as far south as Chile. In the Corynocarpus family, Corynocarpus laevigatus is called laurel of New Zealand, while Laurelia novae-zelandiae belongs to the same genus as Laurelia sempervirens. The tree niaouli grows in Australia, New Caledonia, and Papua.

New Caledonia lies at the northern end of the ancient continent Zealandia, while New Zealand rises at the plate boundary that bisects it. These land masses are two outposts of the Antarctic flora, including Araucarias and Podocarps. At Curio Bay, fossilized logs can be seen of trees closely related to modern Kauri and Norfolk pine that grew on Zealandia about 180 million years ago during the Jurassic period, before it split from Gondwana.[25]

During glacial periods more of Zealandia became a terrestrial rather than a marine environment. Zealandia was originally thought to have no native land mammals, but a recent discovery in 2006 of a fossil mammal jaw from the Miocene in the Otago region shows otherwise.[26]

The New Guinea and Northern Australian ecoregions are closely related. Over time Australia drifted north and became drier; the humid Antarctic flora from Gondwana retreated to the east coast and Tasmania, while the rest of Australia became dominated by sclerophyll forest and xeric shrubs and grasses. Humans arrived in Australia 50–60,000 years ago, and used fire to reshape the vegetation of the continent; as a result, the Antarctic flora, also known as the Rainforest flora in Australia, retreated to a few isolated areas composing less than 2% of Australia's land area.

New Guinea

The eastern end of Malesia, including New Guinea and the Aru Islands of eastern Indonesia, is linked to Australia by a shallow continental shelf, and shares many marsupial mammal and bird taxa with Australia. New Guinea also has many additional elements of the Antarctic flora, including southern beech (Nothofagus) and Eucalypts. New Guinea has the highest mountains in Malesia, and vegetation ranges from tropical lowland forest to tundra.

The highlands of New Guinea and New Britain are home to montane laurel forests, from about 1,000 to 2,500 metres (3,300–8,200 ft) elevation. These forests include species typical of both Northern Hemisphere laurel forests, including Lithocarpus, Ilex, and Lauraceae, and Southern Hemisphere laurel forests, including Southern Beech Nothofagus, Araucaria, Podocarps, and trees of the Myrtle family (Myrtaceae).[8][27] New Guinea and Northern Australia are closely related. Around 40 million years ago, the Indo-Australian tectonic plate began to split apart from the ancient supercontinent Gondwana. As it collided with the Pacific Plate on its northward journey, the high mountain ranges of central New Guinea emerged around 5 million years ago.[28] In the lee of this collision zone, the ancient rock formations of what is now Cape York Peninsula remained largely undisturbed.

Laurel forest ecoregions of New Guinea

The WWF identifies several distinct montane laurel forest ecoregions on New Guinea, New Britain, and New Ireland.[29]

- Central Range montane rain forests

- Huon Peninsula montane rain forests

- New Britain-New Ireland montane rain forests

- Northern New Guinea montane rain forests

- Vogelkop montane rain forests

References

- Abstract at NASA – MODIS: Izquierdo, T; de las Heras, P; Marquez, A (2011). Vegetation indices changes in the cloud forest of La Gomera Island (Canary Islands) and their hydrological implications". Hydrological Processes, 25(10), 1531–41: "[R]esults prove the absence of summer drought stress in the laurel forest implying that the fog drip income is high enough to maintain enough soil moisture".

- Resumen, Aschan, G., María Soledad Jiménez Parrondo, Domingo Morales Méndez, Reiner Lösch (1994), "Aspectos microclimaticos de un bosque de laurisilva en Tenerife / Microclimatic aspects of a Laurel Forest in Tenerife". Vieraea: Folia scientarum biologicarum canariensium, (23), 125–41. Dialnet. (in Spanish).

- Ashton, Peter S. (2003). "Floristic zonation of tree communities on wet tropical mountains revisited". Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 6 (1–2): 87–104. doi:10.1078/1433-8319-00044.

- Tang, Cindy Q.; Ohsawa, Masahiko (1999). "Altitudinal distribution of evergreen broad-leaved trees and their leaf-size pattern on a humid subtropical mountain, Mt. Emei, Sichuan, China". Plant Ecology. Springer Nature. 145 (2): 221–233. doi:10.1023/a:1009856020744. ISSN 1385-0237.

- Otto E. (Otto Emery) Jennings. "Fossil plants from the beds of volcanic ash near Missoula, western Montana" Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, 8(2), p. 417.

- Box, Elgene O.; Chang-Hung Chou; Kazue Fujiwara (1998). "Richness, Climactic Position, and Biogeographic Potential of East Asian Laurophyll Forests, with Particular Reference to Examples from Taiwan" (PDF). Bulletin of the Institute of Environmental Science, Yokohama National University. 24: 61–95. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-02-26.

- Sunset Western Garden Book, 1995:606–607

- Tagawa, Hideo (1995). "Distribution of lucidophyll Oak – Laurel forest formation in Asia and other areas". Tropics. 5 (1/2): 1–40. doi:10.3759/tropics.5.1.

- "MBG: DIVERSITY, ENDEMISM, AND EXTINCTION IN THE FLORA AND VEGETATION OF NEW CALEDONIA". mobot.org.

- "Jian Nan subtropical evergreen forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- Karan, Pradyumna Prasad (2005). Japan in the 21st century: environment, economy, and society. University Press of Kentucky, Lexington. ISBN 978-0-8131-2342-4. p. 25.

- "Borneo montane rain forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- Madeira Laurel Forest, Madeira Wind Birds 2005

- Góis-Marques, Carlos A.; Madeira, José; Menezes de Sequeira, Miguel (7 February 2017). "Inventory and review of the Mio–Pleistocene São Jorge flora (Madeira Island, Portugal): palaeoecological and biogeographical implications". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 16 (2): 159–177. doi:10.1080/14772019.2017.1282991.

- "¿LAURISILVA EN EL PARQUE NATURAL DE LOS ALCORNOCALES?". CUADERNO DE GEOGRAFÍA (in Spanish). 2015-01-28. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- Interpretation Manual of European Union Habitats (PDF). 2007.

- Axelrod, Daniel I. (2000) A Miocene (10-12 Ma) Evergreen Laurel-Oak Forest from Carmel Valley, California. University of California Publications in Geological Sciences 145; April 2000. 3rd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-09839-8.

- Michael G. Barbour, Todd Keeler-Wolf, Allan A. Schoenherr (2007). Terrestrial vegetation of California. Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-1-282-35915-4, p. 56

- "Talamancan montane forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 1 June 2011.

- "Araucaria moist forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- "Serra do Mar coastal forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- Li, H.M.; Zhou, Z.K. (2007). "Fossil nothofagaceous leaves from the Eocene of western Antarctica and their bearing on the origin, dispersal and systematics of Nothofagus". Science in China. 50 (10): 1525–1535. doi:10.1007/s11430-007-0102-0.

- Fujiwara, Kazue and Elgene O. Box (1999). "Evergreen Broad-Leaved Forests in Japan and Eastern North America: Vegetation Shift under Climactic Warming" in Conference on Recent Shifts in Vegetation Boundaries of Deciduous Forests, Frank Klötzl, G.-R. Walther, eds. Basel: Birkhauser, ISBN 978-3-7643-6086-3.

- Keith Lewis; Scott D. Nodder; Lionel Carter (11 January 2007). "Zealandia: the New Zealand continent". Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 22 February 2007.

- Fossil forest: Features of Curio Bay/Porpoise Bay Archived 2008-10-17 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 2007-11-06

- Campbell, Hamish; Gerard Hutching (2007). In Search of Ancient New Zealand. North Shore, New Zealand: Penguin Books. pp. 183–184. ISBN 978-0-14-302088-2.

- "Central Range montane rain forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved June 4, 2011.

- Frith, D.W., Frith, C.B. (1995). Cape York Peninsula: A Natural History. Chatswood: Reed Books Australia. Reprinted with amendments in 2006. ISBN 0-7301-0469-9.

- Wikramanayake, Eric; Eric Dinerstein; Colby J. Loucks; et al. (2002). Terrestrial Ecoregions of the Indo-Pacific: a Conservation Assessment. Washington, DC: Island Press. ISBN 978-1-55963-923-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Laurisilva. |