Betula utilis

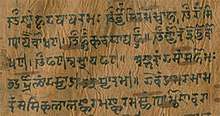

Betula utilis, the Himalayan birch (bhojpatra, Sanskrit: भूर्ज bhūrjá), is a deciduous tree native to the Western Himalayas, growing at elevations up to 4,500 m (14,800 ft). The specific epithet, utilis, refers to the many uses of the different parts of the tree.[1] The white, paper-like bark was used in ancient times for writing Sanskrit scriptures and texts.[2] It is still used as paper for the writing of sacred mantras, with the bark placed in an amulet and worn for protection.[3] Selected varieties are used for landscaping throughout the world, even while some areas of its native habitat are being lost due to overuse of the tree for firewood.

| Betula utilis | |

|---|---|

_I_IMG_3405.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Betulaceae |

| Genus: | Betula |

| Subgenus: | Betula subg. Neurobetula |

| Species: | B. utilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Betula utilis | |

| Synonyms | |

|

B. bhojpatra Wall. | |

Taxonomy

Betula utilis was described and named by botanist David Don in his Prodromus Florae Nepalensis (1825), from specimens collected by Nathaniel Wallich in Nepal in 1820.[4][5] Betula jacquemontii (Spach), first described and named in 1841, was later found to be a variety of B. utilis, and is now Betula utilis var. jacquemontii.[6]

Description

In its native habitat, B. utilis tends to form forests, growing as a shrub or tree reaching up to 20 m (66 ft) tall. It frequently grows among scattered conifers, with an undergrowth of shrubs that typically includes evergreen Rhododendron. The tree depends on moisture from snowmelt, rather than from the monsoon rains. They often have very bent growth due to the pressure of the deep winter snow in the Himalaya.[1]

Leaves are ovate, 5 to 10 cm (2.0 to 3.9 in) long, with serrated margins, and slightly hairy. Flowering occurs from May–July, with only a few male catkins, and short, single (sometimes paired) female catkins. The perianth has four parts in male flowers, and is absent in the female flowers. Fruits ripen in September–October.[1][7]

The thin, papery bark is very shiny, reddish brown, reddish white, or white, with horizontal lenticels. The bark peels off in broad, horizontal belts, making it very usable for creating even large pages for texts.[1] A fungal growth, locally called bhurja-granthi, forms black lumps on the tree weighing up to 1 kg.[7]

The wood is very hard and heavy, and quite brittle. The heartwood is pink or light reddish brown.[8]

History and use

The bark of Himalayan birch was used centuries ago in India as paper for writing lengthy scriptures and texts in Sanskrit and other scripts, particularly in historical Kashmir. Its use as paper for books is mentioned by early Sanskrit writers Kalidasa (c. 4th century CE), Sushruta (c. 3rd century CE), and Varahamihira (6th century CE). In the late 19th century, Kashmiri pandits reported all of their books were written on Himalayan birch bark until Akbar introduced paper in the 16th century.[2] The Sanskrit word for the tree is bhûrja—sharing a similarity with other Indo-European words that provide the origin for the common name "birch".[9]

The bark is still used for writing sacred mantras, which are placed in an amulet and worn around the neck for protection or blessing.[2][3] This practice was mentioned as early as the 8th or 9th century CE, in the Lakshmi Tantra, a Pancaratra text.[10] According to legend, the bark was also used as clothing by attendants of Lord Shiva.[7]

The bark is widely used for packaging material (particularly butter), roof construction, umbrella covers, bandages, and more. The wood is used for bridge construction, and the foliage for fodder. The most widespread use is for firewood, which has caused large areas of habitat to be eliminated or reduced.[1] Parts of the plant, including the fungal growth (bhurja-granthi) have also long been used in local traditional medicine.[7]

Conservation

Deforestation due to overuse of the tree has caused loss of habitat for many native groves of B. utilis (locally called bhojpatra in the Indian Himalaya). The first high-altitude bhojpatra nursery was established in 1993 at Chirbasa, just above Gangotri, where many Hindus go on pilgrimage to the source of the sacred Ganges river. Dr. Harshvanti Bisht, a Himalayan mountaineer, established the first nursery and continues to expand the reforestation of bhojpatra in the Gangotri area and inside Gangotri National Park. About 12,500 bhojpatra saplings had been planted in the area by the year 2000.[11] In recent years, attempts have been made to ban the collection of bhojpatra trees in the Gangotri area.[12]

Varieties and cultivars

Many named varieties and cultivars are used in landscaping throughout the world. In the eastern end of the tree's native distribution, several forms have orange- or copper-colored bark. Betula utilis var. jacquemontii, from the western end of the native habitat, is widely used because several cultivars have especially white bark. The following have gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit:-

The bark of 'Wakehurst Place Chocolate', as the name implies, is dark brown to nearly black.[20]

References

- Liu, Cuirong; Elvin, Mark (1998). Sediments of time: environment and society in Chinese history. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 0-521-56381-X.

- Müller, Friedrich Max (1881). Selected essays on language, mythology and religion, Volume 2. Longmans, Green, and Co. pp. 335–336fn.

- Wheeler, David Martyn (2008). Hortus Revisited: A 21st Birthday Anthology. London: Frances Lincoln. p. 119. ISBN 0-7112-2738-1.

- Don, David (1823). Prodromus floræ Nepalensis, sive Enumeratio vegetabilium, quæ in itinere. p. 58.

- Santisuk, Thawatchai (November 2009). "THAI FOREST BULLETIN" (PDF). The Forest Herbarium (BKF). p. 172. Retrieved 12 June 2010.

- "Betulaceae Betula jacquemontii Spach". International Plant Names Index. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- Chauhan, Narain Singh (1999). Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing Company. p. 125. ISBN 81-7387-098-5.

- "Betula utilis D. Don". Flora of China. Harvard University. 4: 309. 1994.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 38. ISBN 0-521-29944-6.

- Gupta, Sanjukta (1972). Laksmi Tantra a Pancaratra text; Orientalia Rheno-traiectina; v.15. Brill Archive. p. xxi.

- Jain, Anmol (2008-11-16). "Mountaineer on mission green". The Tribune, Chandigarh, India. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "Kanwar mela: Alert in Uttarakhand". Times of India. 2007-08-08. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Betula utilis var. jacquemontii 'Doorenbos'". Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Betula 'Fascination'". RHS. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "Betula utilis 'Forest Blush'". RHS. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Betula utilis var. jacquemontii 'Grayswood Ghost'". Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Betula utilis var. jacquemontii 'Jermyns'". Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- "Betula utilis 'Jermyns'". RHS. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "RHS Plant Selector - Betula utilis var. jacquemontii 'Silver Shadow'". Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- Junker,Karan (2007). Gardening with woodland plants. Portland, Or: Timber Press. p. 116. ISBN 0-88192-821-6.