Araucaria

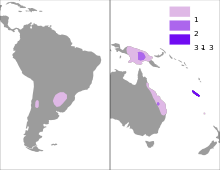

Araucaria ( /ærɔːˈkɛəriə/; original pronunciation: [a.ɾawˈka. ɾja])[4] is a genus of evergreen coniferous trees in the family Araucariaceae. There are 20 extant species in New Caledonia (where 14 species are endemic, see New Caledonian Araucaria), Norfolk Island, eastern Australia, New Guinea, Argentina, Chile, Brazil, and Paraguay.

| Araucaria | |

|---|---|

| |

| A. araucana growing around a lake in Neuquén, Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Division: | Pinophyta |

| Class: | Pinopsida |

| Order: | Pinales |

| Family: | Araucariaceae |

| Genus: | Araucaria Juss. |

| Type species | |

| Araucaria araucana [3] | |

| |

| Worldwide distribution of Araucaria species. | |

Description

Araucaria are mainly large trees with a massive erect stem, reaching a height of 5–80 metres (16–262 ft). The horizontal, spreading branches grow in whorls and are covered with leathery or needle-like leaves. In some species, the leaves are narrow, awl-shaped and lanceolate, barely overlapping each other; in others they are broad and flat, and overlap broadly.[5]

The trees are mostly dioecious, with male and female cones found on separate trees,[6] though occasional individuals are monoecious or change sex with time.[7] The female cones, usually high on the top of the tree, are globose, and vary in size among species from 7 to 25 centimetres (2.8 to 9.8 in) diameter. They contain 80–200 large edible seeds, similar to pine nuts, though larger. The male cones are smaller, 4–10 cm (1.6–3.9 in) long, and narrow to broad cylindrical, 1.5–5.0 cm (0.6–2.0 in) broad.

The genus is familiar to many people as the genus of the distinctive Chilean pine or monkey-puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana). The genus is named after the Spanish exonym Araucano ("from Arauco") applied to the Mapuche of central Chile and south-west Argentina, whose territory incorporates natural stands of this genus. The Mapuche people call it pehuén, and consider it sacred.[5] Some Mapuche living in the Andes name themselves Pehuenches ("people of the pehuén") as they traditionally harvested the seeds extensively for food.[8][9]

No distinct vernacular name exists for the genus. Many are called "pine", although they are only distantly related to true pines, in the genus Pinus.

Distribution and paleoecology

Members of Araucaria are found in Chile, Argentina, Brazil, New Caledonia, Norfolk Island, Australia, and New Guinea. There is also a significant, naturalized population of Araucaria columnaris – "Cook's pine" – on the island of Lanai, in Hawaii, USA.[10] Many if not all current populations are relicts, and of restricted distribution. They are found in forest and maquis shrubland, with an affinity for exposed sites. These columnar trees are living fossils, dating back to early in the Mesozoic age. Fossil records show that the genus also formerly occurred in the northern hemisphere until the end of the Cretaceous period.

By far the greatest diversity exists in New Caledonia, due to the island's long isolation and stability.[5] Much of New Caledonia is composed of ultramafic rock with serpentine soils, with low levels of nutrients, but high levels of metals such as nickel.[11] Consequently, its endemic Araucaria species are adapted to these conditions, and many species have been severely affected by nickel mining in New Caledonia and are now considered threatened or endangered, due to their habitat lying in prime areas for nickel mining activities.

There is evidence to suggest that the long necks of sauropod dinosaurs may have evolved specifically to browse the foliage of the typically very tall Araucaria trees. The global distribution of vast forests of Araucaria during the Jurassic makes it likely that they were the major high energy food source for adult sauropods.[12]

Classification and species list

There are four extant sections and two extinct sections in the genus, sometimes treated as separate genera.[5][13][14] Genetic studies indicate that the extant members of the genus can be subdivided into two large clades – the first consisting of the sections Araucaria, Bunya, and Intermedia; and the second of the strongly monophyletic section Eutacta. Sections Eutacta and Bunya are both the oldest taxa of the genus, with Eutacta possibly older.[15]

- Taxa marked with † are extinct.

- Section Araucaria. Leaves broad; cones more than 12 cm (4.7 in) diameter; seed germination hypogeal. Syn. sect. Columbea; sometimes includes Intermedia and Bunya

- Araucaria angustifolia – Paraná pine (obsolete: Brazilian pine, candelabra tree); southern and southeastern Brazil, northeastern Argentina.

- Araucaria araucana – monkey-puzzle or pehuén (obsolete: Chile pine); central Chile & western Argentina.

- †Araucaria nipponensis – Japan and Sakhalin (Upper Cretaceous)[16]

- Section Bunya. Contains only one living species. Produces recalcitrant seeds with hypogeal (cryptocotylar) germination,[17] though extinct species may have exhibited epigeal germination.[15]

- Araucaria bidwillii – bunya-bunya; Eastern Australia

- †Araucaria brownii - England

- †Araucaria mirabilis – Patagonia (Middle Jurassic)

- †Araucaria sphaerocarpa - England (Middle Jurassic)

- Section Intermedia. Contains only one living species. Produces recalcitrant seeds

- Araucaria hunsteinii – klinki; New Guinea

- †Araucaria haastii - New Zealand (Cretaceous)

- Section Eutacta. Leaves narrow, awl-like; cones less than 12 cm (4.7 in) diameter; seed germination epigeal

- Araucaria bernieri – New Caledonia

- Araucaria biramulata – New Caledonia

- Araucaria columnaris – Cook pine; New Caledonia

- Araucaria cunninghamii – Moreton Bay pine, hoop pine; Eastern Australia, New Guinea

- Araucaria goroensis – New Caledonia

- Araucaria heterophylla – Norfolk Island pine; Norfolk Island

- Araucaria humboldtensis – New Caledonia

- Araucaria laubenfelsii – New Caledonia

- Araucaria luxurians – New Caledonia

- Araucaria montana – New Caledonia

- Araucaria muelleri – New Caledonia

- Araucaria nemorosa – New Caledonia

- Araucaria rulei – New Caledonia

- Araucaria schmidii – New Caledonia

- Araucaria scopulorum – New Caledonia

- Araucaria subulata – New Caledonia

- †Araucaria lignitici – (Paleogene) Yallourn, Victoria[18]

- †Section Yezonia. Extinct. Contains only one species

- †Araucaria vulgaris – Japan (Late Cretaceous)

- †Section Perpendicula. Extinct. Contains only one species

- †Araucaria desmondii - New Zealand (Late Cretaceous)

- incertae sedis

- †Araucaria beipiaoensis

- †Araucaria fibrosa

- †Araucaria marensii – La Meseta Formation, Antarctica & Santa Cruz Formation, Argentina[19][20]

- †Araucaria nihongii – Japan

- †Araucaria taieriensis - New Zealand [21]

Araucaria bindrabunensis (previously classified under section Bunya) has been transferred to the genus Araucarites.

Uses

Some of the species are relatively common in cultivation because of their distinctive, formal symmetrical growth habit. Several species are economically important for timber production.

Food

The edible large seeds of A. araucana, A. angustifolia and A. bidwillii — also known as Araucaria nuts,[22] and often called, although improperly, pine nuts — are eaten as food (particularly among the Mapuche people and Native Australians).[5] In South America Araucaria nuts or seeds are called piñas, pinhas, piñones or pinhões, like pine nuts in Europe.

Pharmacological activity

Pharmacological reports on genus Araucaria are anti-ulcer, antiviral, neuro-protective, anti-depressant and anti-coagulant.[23]

References

- Michael Knapp; Ragini Mudaliar; David Havell; Steven J. Wagstaff; Peter J. Lockhart (2007). "The drowning of New Zealand and the problem of Agathis". Systematic Biology. 56 (5): 862–870. doi:10.1080/10635150701636412. PMID 17957581.

- S. Gilmore; K. D. Hill (1997). "Relationships of the Wollemi Pine (Wollemia nobilis) and a molecular phylogeny of the Araucariaceae" (PDF). Telopea. 7 (3): 275–290. doi:10.7751/telopea19971020.

- K. D. Hill (1998). "Araucaria". Flora of Australia Online. Australian Biological Resources Study. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- "araucaria". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Christopher J. Earle (12 December 2010). "Araucaria Jussieu 1789". The Gymnosperm Database. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Practical seedling growing: Growing Araucaria from seeds". Arboretum de Villardebelle. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- Michael G. Simpson (2010). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-12-374380-0.

- "Araucaria columnaris". National Tropical Botanical Garden. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- Francisco P. Moreno (November 2004). "Pehuenches: "The people from the Araucarias forests"". Museo de la Patagonia. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- The Pine Trees of Lanai

- Plants of New Caledonia. Atlanta botanical gardens

- Jürgen Hummel; Carole T. Gee; Karl-Heinz Südekum; P. Martin Sander; Gunther Nogge; Marcus Clauss (2008). "In vitro digestibility of fern and gymnosperm foliage: implications for sauropod feeding ecology and diet selection". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1638): 1015–1021. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1728. PMC 2600911. PMID 18252667.

- Michael Black; H. W. Pritchard (2002). Desiccation and survival in plants: Drying without dying. CAB International. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-85199-534-2.

- James E. Eckenwalder (2009). Conifers of the World: the Complete Reference. Timber Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-88192-974-4.

- Hiroaki Setoguchi; Takeshi Asakawa Osawa; Jean-Cristophe Pintaud; Tanguy Jaffré; Jean-Marie Veillon (1998). "Phylogenetic relationships within Araucariaceae based on rbcL gene sequences" (PDF). American Journal of Botany. 85 (11): 1507–1516. doi:10.2307/2446478. JSTOR 2446478. PMID 21680310.

- Mary E. Dettmann; H. Trevor Clifford (2005). "Biogeography of Araucariaceae" (PDF). In J. Dargavel (ed.). Australia and New Zealand Forest Histories. Araucaria Forests. Occasional Publication 2. Australian Forest History Society. pp. 1–9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-09-13.

- Erich Götz (1980). Pteridophytes and Gymnosperms. Springer. p. 295. ISBN 978-3-540-51794-8.

- Cookson, Isabel C.; Duigan, Suzanne L. (1951). "Tertiary Araucariaceae From South-Eastern Australia, With Notes on Living Species". Australian Journal of Biological Sciences. 4 (4): 415–49. doi:10.1071/BI9510415.

- Araucaria marensii at Fossilworks.org

- Vizcaíno, Sergio F.; Kay, Richard F.; Bargo, M. Susana (2012). "Araucaria+marensii" Early Miocene Paleobiology in Patagonia: High-Latitude Paleocommunities of the Santa Cruz Formation. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 9781139576413. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- Pole, Mike (2008). "The record of Araucariaceae macrofossils in New Zealand". Alcheringa. 32 (4): 405–26. doi:10.1080/03115510802417935.

- Québec Amerique, ed. (1996). "Pine nut". The Visual Food Encyclopedia. p. 280. ISBN 9782764408988.

- Aslam, M.S; Ijaz, A.S (2013). "Phytochemical and ethno-pharmacological review of the genus Araucaria". Journal of Tropical Pharmaceutical Research. Review Article. 12 (4): 651–659. doi:10.4314/tjpr.v12i4.31.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Araucaria. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Araucaria |

- "Araucaria". Gymnosperm Database.

- "Araucaria Research".