Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Latin language recognized as a standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. In some later periods, it was regarded as good or proper Latin, with following versions viewed as debased, degenerate, vulgar, or corrupted. The word Latin is now understood by default to mean "Classical Latin"; for example, modern Latin textbooks almost exclusively teach Classical Latin.

| Classical Latin | |

|---|---|

| LINGVA LATINA, lingua latīna | |

Latin inscription in the Colosseum | |

| Pronunciation | [laˈtiːnɪtaːs] |

| Native to | Roman Republic, Roman Empire |

| Region | Mare Nostrum region |

| Era | 75 BC to AD 3rd century, when it developed into Late Latin |

Indo-European

| |

Early form | |

| Classical Latin alphabet | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Roman Republic, Roman Empire |

| Regulated by | Schools of grammar and rhetoric |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

lat-cla | |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere | 51-AAB-aaa |

The range of Latin, AD 60 | |

Cicero and his contemporaries of the late republic used lingua latina and sermo latinus versions of the Latin language. Conversely, the Greeks used Vulgar Latin (sermo vulgaris and sermo vulgi) in their vernacular, written as latinitas,[note 1] or "Latinity" (which implies "good") when combined. It was also called sermo familiaris ("speech of the good families"), sermo urbanus ("speech of the city"), and in rare cases sermo nobilis ("noble speech"). Besides latinitas, it was mainly called latine (adverb for "in good Latin"), or latinius (comparative adverb for "in better Latin").

Latinitas was spoken and written. It was the language taught in schools. Prescriptive rules therefore applied to it, and when special subjects like poetry or rhetoric were taken into consideration, additional rules applied. Since spoken Latinitas has become extinct (in favor of subsequent registers), the rules of politus (polished) texts may give the appearance of an artificial language. However, Latinitas was a form of sermo (spoken language), and as such, retains spontaneity. No texts by Classical Latin authors are noted for the type of rigidity evidenced by stylized art, with the exception of repetitious abbreviations and stock phrases found on inscriptions. For example, "IESVS NAZARENVS REX IVDAEORVM" ("Jesus Nazarenus Rex Judaeorum") was the titulus written on the placard above Jesus' head on the Cross, and is a rather famous example of Classical Latin.

Philological constructs

Classical

"Good Latin" in philology is known as "classical" Latin literature. The term refers to the canonical relevance of literary works written in Latin in the late Roman Republic, and early to middle Roman Empire. "[T]hat is to say, that of belonging to an exclusive group of authors (or works) that were considered to be emblematic of a certain genre."[1] The term classicus (masculine plural classici) was devised by the Romans to translate Greek ἐγκριθέντες (encrithentes), and "select" which refers to authors who wrote in a form of Greek that was considered model. Before then, the term classis, in addition to being a naval fleet, was a social class in one of the diachronic divisions of Roman society in accordance with property ownership under the Roman constitution.[2] The word is a transliteration of Greek κλῆσις (clēsis, or "calling") used to rank army draftees by property from first to fifth class.

Classicus refers to those in the primae classis ("first class"), such as the authors of polished works of Latinitas, or sermo urbanus. It contains nuances of the certified and the authentic, or testis classicus ("reliable witness"). It was under this construct that Marcus Cornelius Fronto (an African-Roman lawyer and language teacher) used scriptores classici ("first-class" or "reliable authors") in the second century AD. Their works were be viewed as models of good Latin.[3] This is the first known reference (possibly innovated during this time) to Classical Latin applied by authors, evidenced in the authentic language of their works.[4]

Canonical

Imitating Greek grammarians, Romans such as Quintilian drew up lists termed indices or ordines modeled after the ones created by the Greeks, which were called pinakes. The Greek lists were considered classical, or recepti scriptores ("select writers"). Aulus Gellius includes authors like Plautus, who are considered writers of Old Latin and not strictly in the period of classical Latin. The classical Romans distinguished Old Latin as prisca Latinitas and not sermo vulgaris. Each author's work in the Roman lists was considered equivalent to one in the Greek. In example, Ennius was the Latin Homer, Aeneid was the equivalent of Iliad, etc. The lists of classical authors were as far as the Roman grammarians went in developing a philology. The topic remained at that point while interest in the classici scriptores declined in the medieval period as the best form of the language yielded to medieval Latin, inferior to classical standards.

The Renaissance saw a revival in Roman culture, and with it, the return of Classic ("the best") Latin. Thomas Sébillet's Art Poétique (1548), "les bons et classiques poètes françois", refers to Jean de Meun and Alain Chartier, who the first modern application of the words. According to Merriam Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, the term classical (from classicus) entered modern English in 1599, some 50 years after its re-introduction to the continent. In Governor William Bradford's Dialogue (1648), he referred to synods of a separatist church as "classical meetings", defined by meetings between "young men" from New England and "ancient men" from Holland and England.[5] In 1715, Laurence Echard's Classical Geographical Dictionary was published.[6] In 1736, Robert Ainsworth's Thesaurus Linguae Latinae Compendarius turned English words and expressions into "proper and classical Latin."[7] In 1768, David Ruhnken's Critical History of the Greek Orators recast the molded view of the classical by applying the word "canon" to the pinakes of orators after the Biblical canon, or list of authentic books of the Bible. In doing so, Ruhnken had secular catechism in mind.[8]

Ages of Latin

In 1870, Wilhelm Sigismund Teuffel's Geschichte der Römischen Literatur (A History of Roman Literature) defined the philological notion of classical Latin based on the metaphoric uses of the ancient myth, Ages of Man. It was viewed as a universal standard, marking the Golden and Silver Ages of classical Latin. Shortly after Wilhem Wagner published Teuffel's work in German, he translated it to English (1873). Teuffel's classification divides the chronology of classical Latin authors into several periods according to political events rather than by style. His work (with modifications) is still in use today.

Teuffel went on to publish other editions, but the English translation of A History of Roman Literature gained immediate success. In 1877, Charles Thomas Cruttwell produced a similar work in English. In his preface, Cruttwell notes, "Teuffel's admirable history, without which many chapters in the present work could not have attained completeness." He also credits Wagner.

Cruttwell adopts the time periods found in Teuffel's work, but he presents a detailed analysis of style, whereas Teuffel was more concerned with history. Like Teuffel, Cruttwell encountered issues while attempting to condense the voluminous details of time periods in an effort to capture the meaning of phases found in their various writing styles. Like Teuffel, he has trouble finding a name for the first of the three periods (the current Old Latin phase), calling it "from Livius to Sulla." He says the language "is marked by immaturity of art and language, by a vigorous but ill-disciplined imitation of Greek poetical models, and in prose by a dry sententiousness of style, gradually giving way to a clear and fluent strength..." These abstracts have little meaning to those not well-versed in Latin literature. In fact, Cruttwell admits "The ancients, indeed, saw a difference between Ennius, Pacuvius, and Accius, but it may be questioned whether the advance would be perceptible by us."

In time, some of Cruttwell's ideas become established in Latin philology. While praising the application of rules to classical Latin (most intensely in the Golden Age, he says "In gaining accuracy, however, classical Latin suffered a grievous loss. It became cultivated as distinct from a natural language... Spontaneity, therefore, became impossible and soon invention also ceased... In a certain sense, therefore, Latin was studied as a dead language, while it was still a living."[9]

Also problematic in Teuffel's scheme is its appropriateness to the concept of classical Latin. Cruttwell addresses the issue by altering the concept of the classical. The "best" Latin is defined as "golden" Latin, the second of the three periods. The other two periods (considered "classical") are left hanging. By assigning the term "pre-classical" to Old Latin and implicating it to post-classical (or post-Augustan) and silver Latin, Cruttwell realized that his construct was not accordance with ancient usage and assertions: "[T]he epithet classical is by many restricted to the authors who wrote in it [golden Latin]. It is best, however, not to narrow unnecessarily the sphere of classicity; to exclude Terence on the one hand or Tacitus and Pliny on the other, would savour of artificial restriction rather than that of a natural classification." The contradiction remains—Terence is, and is not a classical author, depending on context.[10]

Authors of the Golden Age

Teuffel's definition of the "First Period" of Latin was based on inscriptions, fragments, and the literary works of the earliest known authors. Though he does use the term "Old Roman" at one point, most of these findings remain unnamed. Teuffel presents the Second Period in his major work, das goldene Zeitalter der römischen Literatur (Golden Age of Roman Literature), dated 671–767 AUC (83 BC – 14 AD), according to his own recollection. The timeframe is marked by the dictatorship of Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix and the death of the emperor Augustus.[11][12] Wagner's translation of Teuffel's writing is as follows:

The golden age of the Roman literature is that period in which the climax was reached in the perfection of form, and in most respects also in the methodical treatment of the subject-matters. It may be subdivided between the generations, in the first of which (the Ciceronian Age) prose culminated, while poetry was principally developed in the Augustan Age.

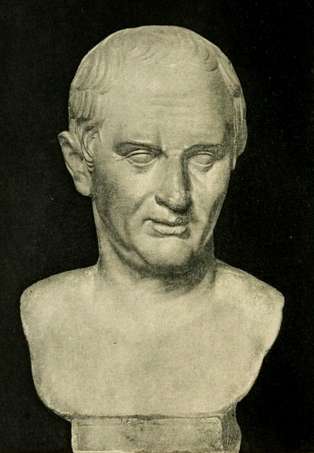

The Ciceronian Age was dated 671–711 AUC (83–43 BC), ending just after the death of Marcus Tullius Cicero. The Augustan 711–67 AUC (43 BC – 14 AD) ends with the death of Augustus. The Ciceronian Age is further divided by the consulship of Cicero in 691 AUC (63 BC) into a first and second half. Authors are assigned to these periods by years of principal achievements.

The Golden Age had already made an appearance in German philology, but in a less-systematic way. In a translation of Bielfeld's Elements of universal erudition (1770):

The Second Age of Latin began about the time of Caesar [his ages are different from Teuffel's], and ended with Tiberius. This is what is called the Augustan Age, which was perhaps of all others the most brilliant, a period at which it should seem as if the greatest men, and the immortal authors, had met together upon the earth, in order to write the Latin language in its utmost purity and perfection...[13] and of Tacitus, his conceits and sententious style is not that of the golden age...[14]

Evidently, Teuffel received ideas about golden and silver Latin from an existing tradition and embedded them in a new system, transforming them as he thought best.

In Cruttwell's introduction, the Golden Age is dated 80 BC – 14 AD (from Cicero to Ovid), which corresponds to Teuffel's findings. Of the "Second Period," Cruttwell paraphrases Teuffel by saying it "represents the highest excellence in prose and poetry." The Ciceronian Age (known today as the "Republican Period") is dated 80–42 BC, marked by the Battle of Philippi. Cruttwell omits the first half of Teuffel's Ciceronian, and starts the Golden Age at Cicero's consulship in 63 BC—an error perpetuated in Cruttwell's second edition. He likely meant 80 BC, as he includes Varro in Golden Latin. Teuffel's Augustan Age is Cruttwell's Augustan Epoch (42 BC – 14 AD).

Republican

The literary histories list includes all authors from Canonical to the Ciceronian Age—even those whose works are fragmented or missing altogether. With the exception of a few major writers, such as Cicero, Caesar, Virgil and Catullus, ancient accounts of Republican literature praise jurists and orators whose writings, and analyses of various styles of language cannot be verified because there are no surviving records. The reputations of Aquilius Gallus, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, and many others who gained notoriety without readable works, are presumed by their association within the Golden Age. A list of canonical authors of the period whose works survived in whole or in part is shown here:

- Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC), highly influential grammarian

- Titus Pomponius Atticus (112/109 – 35/32), publisher and correspondent of Cicero

- Marcus Tullius Cicero (106–43 BC), orator, philosopher, essayist, whose works define golden Latin prose and are used in Latin curricula beyond the elementary level

- Servius Sulpicius Rufus (106–43 BC), jurist, poet

- Decimus Laberius (105–43 BC), writer of mimes

- Marcus Furius Bibaculus (1st century BC), writer of ludicra

- Gaius Julius Caesar (103–44 BC), general, statesman, historian

- Gaius Oppius (1st century BC), secretary to Julius Caesar, probable author under Caesar's name

- Gaius Matius (1st century BC), public figure, correspondent with Cicero

- Cornelius Nepos (100–24 BC), biographer

- Publilius Syrus (1st century BC), writer of mimes and maxims

- Quintus Cornificius (1st century BC), public figure and writer on rhetoric

- Titus Lucretius Carus (Lucretius; 94–50 BC), poet, philosopher

- Publius Nigidius Figulus (98–45 BC), public officer, grammarian

- Aulus Hirtius (90–43 BC), public officer, military historian

- Gaius Helvius Cinna (1st century BC), poet

- Marcus Caelius Rufus (87–48 BC), orator, correspondent with Cicero

- Gaius Sallustius Crispus (86–34 BC), historian

- Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (Cato the Younger; 95–46 BC), orator

- Publius Valerius Cato (1st century BC), poet, grammarian

- Gaius Valerius Catullus (Catullus; 84–54 BC), poet

- Gaius Licinius Macer Calvus (82–47 BC), orator, poet

Augustan

The Golden Age is divided by the assassination of Julius Caesar. In the wars that followed, a generation of Republican literary figures were lost. Marcus Tullius Cicero was beheaded in the streets as he inquired among his litter about a disturbance. Cicero and his contemporaries were replaced by a new generation who spent their formidable years under the old constructs, and forced to make their mark under the watchful eye of a new emperor. The demand for great orators had ceased,[15] shifting to an emphasis on poetry. Other than the historian Livy, the most remarkable writers of the period were the poets Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. Although Augustus evidenced some toleration to republican sympathizers, he exiled Ovid, and imperial tolerance ended with the continuance of the Julio-Claudian dynasty.

Augustan writers include:

- Publius Vergilius Maro (Virgil, spelled also as Vergil; 70–19 BC),

- Quintus Horatius Flaccus (Horace; 65–8 BC), known for lyric poetry and satires

- Sextus Aurelius Propertius (50–15 BC), poet

- Albius Tibullus (54–19 BC), elegiac poet

- Publius Ovidius Naso (Ovid; 43 BC – AD 18), poet

- Titus Livius (Livy; 64 BC – AD 12), historian

- Grattius Faliscus (a contemporary of Ovid), poet

- Marcus Manilius (1st century BC and AD), astrologer, poet

- Gaius Julius Hyginus (64 BC – AD 17), librarian, poet, mythographer

- Marcus Verrius Flaccus (55 BC – AD 20), grammarian, philologist, calendarist

- Marcus Vitruvius Pollio (80-70 BC — after 15 BC), engineer, architect

- Marcus Antistius Labeo (d. AD 10 or 11), jurist, philologist

- Lucius Cestius Pius (1st century BC & AD), Latin educator

- Gnaeus Pompeius Trogus (1st century BC), historian, naturalist

- Marcus Porcius Latro (1st century BC), rhetorician

- Gaius Valgius Rufus (consul 12 BC), poet

Authors of the Silver Age

In his second volume, Imperial Period, Teuffel initiated a slight alteration in approach, making it clear that his terms applied to Latin and not just to the period. He also changed his dating scheme from AUC to modern BC/AD. Though he introduces das silberne Zeitalter der römischen Literatur, (The Silver Age of Roman Literature) [16] from the death of Augustus to the death of Trajan (14–117 AD), he also mentions parts of a work by Seneca the Elder, a wenig Einfluss der silbernen Latinität (a slight influence of silver Latin). It's clear that his mindset had shifted from Golden and Silver Ages to Golden and Silver Latin, also to include Latinitas, which at this point must be interpreted as Classical Latin. He may have been influenced in that regard by one of his sources E. Opitz, who in 1852 had published specimen lexilogiae argenteae latinitatis, which includes Silver Latinity.[17] Though Teuffel's First Period was equivalent to Old Latin and his Second Period was equal to the Golden Age, his Third Period die römische Kaiserheit encompasses both the Silver Age and the centuries now termed Late Latin, in which the forms seemed to break loose from their foundation and float freely. That is, men of literature were confounded about the meaning of "good Latin." The last iteration of Classical Latin is known as Silver Latin. The Silver Age is the first of the Imperial Period, and is divided into die Zeit der julischen Dynastie (14–68); die Zeit der flavischen Dynastie (69–96), and die Zeit des Nerva und Trajan (96–117). Subsequently, Teuffel goes over to a century scheme: 2nd, 3rd, etc., through 6th. His later editions (which came about towards the end of the 19th century) divide the Imperial Age into parts: 1st century (Silver Age), 2nd century ( the Hadrian and the Antonines), and the 3rd through 6th centuries. Of the Silver Age proper, Tueffel points out that anything like freedom of speech had vanished with Tiberius:[18]

...the continual apprehension in which men lived caused a restless versatility... Simple or natural composition was considered insipid; the aim of language was to be brilliant... Hence it was dressed up with abundant tinsel of epigrams, rhetorical figures and poetical terms... Mannerism supplanted style, and bombastic pathos took the place of quiet power.

The content of new literary works was continually proscribed by the emperor, who exiled or executed existing authors and played the role of literary man, himself (typically badly). Artists therefore went into a repertory of new and dazzling mannerisms, which Teuffel calls "utter unreality." Cruttwell picks up this theme:[19]

The foremost of these [characteristics] is unreality, arising from the extinction of freedom... Hence arose a declamatory tone, which strove by frigid and almost hysterical exaggeration to make up for the healthy stimulus afforded by daily contact with affairs. The vein of artificial rhetoric, antithesis and epigram... owes its origin to this forced contentment with an uncongenial sphere. With the decay of freedom, taste sank...

In Cruttwell's view (which had not been expressed by Teuffel), Silver Latin was a "rank, weed-grown garden," a "decline."[20] Cruttwell had already decried what he saw as a loss of spontaneity in Golden Latin. Teuffel regarded the Silver Age as a loss of natural language, and therefore of spontaneity, implying that it was last seen in the Golden Age. Instead, Tiberius brought about a "sudden collapse of letters." The idea of a decline had been dominant in English society since Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Once again, Cruttwell evidences some unease with his stock pronouncements: "The Natural History of Pliny shows how much remained to be done in fields of great interest." The idea of Pliny as a model is not consistent with any sort of decline. Moreover, Pliny did his best work under emperors who were as tolerant as Augustus had been. To include some of the best writings of the Silver Age, Cruttwell extended the period through the death of Marcus Aurelius (180 AD). The philosophic prose of a good emperor was in no way compatible with either Teuffel's view of unnatural language, or Cruttwell's depiction of a decline. Having created these constructs, the two philologists found they could not entirely justify them. Apparently, in the worst implication of their views, there was no such thing as Classical Latin by the ancient definition, and some of the very best writing of any period in world history was deemed stilted, degenerate, unnatural language.

The Silver Age furnishes the only two extant Latin novels: Apuleius's The Golden Ass and Petronius's Satyricon.

Perhaps history's best-known example of Classical Latin was written by Pontius Pilate on the placard placed above Jesus' Cross: Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudaeorum, which translates to Jesus the Nazarean the King of the Judeans (Jesus of Nazareth the King of the Jews).

Writers of the Silver Age include:

From the Ides of March to Trajan

- Aulus Cremutius Cordus (died AD 25), historian

- Marcus Velleius Paterculus (19 BC – 31 AD), military officer, historian

- Valerius Maximus (1st century AD), rhetorician

- Masurius Sabinus (1st century AD), jurist

- Phaedrus (15 BC – AD 50), fabulist

- Germanicus Julius Caesar (15 BC – AD 19), royal family, imperial officer, translator

- Aulus Cornelius Celsus (25 BC – AD 50), physician, encyclopedist

- Quintus Curtius Rufus (1st century AD), historian

- Cornelius Bocchus (1st century AD), natural historian

- Pomponius Mela (d. AD 45), geographer

- Lucius Annaeus Seneca (4 BC – AD 65), educator, imperial advisor, philosopher, man of letters

- Titus Calpurnius Siculus (1st century AD or possibly later), poet

- Marcus Valerius Probus (1st century AD), literary critic

- Tiberius Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (10 BC – AD 54), emperor, man of letters, public officer

- Gaius Suetonius Paulinus (1st century AD), general, natural historian

- Lucius Junius Moderatus Columella (AD 4 – 70), military officer, agriculturalist

- Quintus Asconius Pedianus (9 BC – 76 AD), historian, Latinist

- Gaius Musonius Rufus (AD 20 – 101), stoic philosopher

- Quintus Marcius Barea Soranus (1st century AD), imperial officer and public man

- Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23 – 79), imperial officer and encyclopedist

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus (1st century AD), epic poet

- Tiberius Catius Silius Italicus (AD 28 – 103), epic poet

- Gaius Licinius Mucianus (d. AD 76), general, man of letters

- Lucilius Junior (1st century AD), poet

- Aulus Persius Flaccus (34–62 AD), poet and satirist

- Marcus Fabius Quintilianus (35–100 AD), rhetorician

- Sextus Julius Frontinus (AD 40 – 103), engineer, writer

- Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (AD 39 – 65), poet, historian

- Publius Juventius Celsus Titus Aufidius Hoenius Severianus (1st and early 2nd centuries AD), imperial officer, jurist

- Aemilius Asper (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Marcus Valerius Martialis (AD 40 – 104), poet, epigrammatist

- Publius Papinius Statius (AD 45 – 96), poet

- Decimus Junius Juvenalis (1st and 2nd centuries AD), poet, satirist

- Publius Annaeus Florus (1st & 2nd centuries AD), poet, rhetorician and probable author of the epitome of Livy

- Velius Longus (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Flavius Caper (1st & 2nd centuries AD), grammarian

- Publius or Gaius Cornelius Tacitus (AD 56 − 120), imperial officer, historian and in Teuffel's view "the last classic of Roman literature."

- Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (AD 62 – 114), historian, imperial officer and correspondent

Through the death of Marcus Aurelius, 180 AD

Of the additional century granted by Cruttwell to Silver Latin, Teuffel says: "The second century was a happy period for the Roman State, the happiest indeed during the whole Empire... But in the world of letters the lassitude and enervation, which told of Rome's decline, became unmistakeable... its forte is in imitation."[21] Teuffel, however, excepts the jurists; others find other "exceptions", recasting Teuffels's view.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus (70/75 – after 130 AD), biographer

- Marcus Junianus Justinus (2nd century AD), historian

- Lucius Octavius Cornelius Publius Salvius Julianus Aemilianus (AD 110–170), imperial officer, jurist

- Sextus Pomponius (2nd century AD), jurist

- Quintus Terentius Scaurus (2nd century AD), grammarian, literary critic

- Aulus Gellius (AD 125 – after 180), grammarian, polymath

- Lucius Apuleius Platonicus (123/125–180 AD), novelist

- Marcus Cornelius Fronto (AD 100–170), advocate, grammarian

- Gaius Sulpicius Apollinaris (2nd century AD), educator, literary commentator

- Granius Licinianus (2nd century AD), writer

- Lucius Ampelius (2nd century AD), educator

- Gaius (AD 130–180), jurist

- Lucius Volusius Maecianus (2nd century AD), educator, jurist

- Marcus Minucius Felix (d. AD 250), apologist of Christianity, "the first Christian work in Latin" (Teuffel)

- Sextus Julius Africanus (2nd century AD), Christian historian

- Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus (121–180 AD, stoic philosopher, Emperor in Latin, essayist in ancient Greek, role model of the last generation of classicists (Cruttwell)

Stylistic shifts

Style of language refers to repeatable features of speech that are somewhat less general than the fundamental characteristics of a language. The latter provides unity, allowing it to be referred to by a single name. Thus Old Latin, Classical Latin, Vulgar Latin, etc., are not considered different languages, but are all referred to by the term, Latin. This is an ancient practice continued by moderns rather than a philological innovation of recent times. That Latin had case endings is a fundamental feature of the language. Whether a given form of speech prefers to use prepositions such as ad, ex, de, for "to," "from" and "of" rather than simple case endings is a matter of style. Latin has a large number of styles. Each and every author has a style, which typically allows his prose or poetry to be identified by experienced Latinists. Problems in comparative literature have risen out of group styles finding similarity by period, in which case one may speak of Old Latin, Silver Latin, Late Latin as styles or a phase of styles.

The ancient authors themselves first defined style by recognizing different kinds of sermo, or "speech." By valuing Classical Latin as "first class," it was better to write with Latinitas selected by authors who were attuned to literary and upper-class languages of the city as a standardized style. All sermo that differed from it was a different style. Thus, in rhetoric, Cicero was able to define sublime, intermediate, and low styles within Classical Latin. St. Augustine recommend low style for sermons.[22] Style was to be defined by deviation in speech from a standard. Teuffel termed this standard "Golden Latin".

John Edwin Sandys, who was an authority in Latin style for several decades, summarizes the differences between Golden and Silver Latin as follows:[23]

Silver Latin is to be distinguished by:

- "an exaggerated conciseness and point"

- "occasional archaic words and phrases derived from poetry"

- "increase in the number of Greek words in ordinary use" (the Emperor Claudius in Suetonius refers to "both our languages," Latin and Greek[24])

- "literary reminiscences"

- "The literary use of words from the common dialect" (dictare and dictitare as well as classical dicere, "to say")

See also

Notes

- When rarely used in English, the term is capitalized: Latinitas. In Latin it was written all in uppercase: LATINITAS, as were all words in Latin.

References

Citations

- Citroni 2006, p. 204.

- Citroni 2006, p. 205.

- Citroni 2006, p. 206, reported in Aulus Gellius, 9.8.15.

- Citroni 2006, p. 207.

- Bradford, William (1855) [1648]. "Gov. Bradford's Dialogue". In Morton, Nathaniel (ed.). New England's Memorial. Boston: Congregational Board of Publication. p. 330.

- Littlefield 1904, p. 301.

- Ainsworth, Robert (January 1736). "Article XXX: Thesaurus Linguae Latinae Compendarius". The Present State of the Republic of Letters. London: W. Innys and R. Manby. XVII.

- Gorak, Jan (1991). The making of the modern canon: genesis and crisis of a literary idea. London: Athlone. p. 51.

- Cruttwell 1877, p. 3.

- Cruttwell 1877, p. 142.

- Teuffel 1870, p. 216.

- Teuffel 1873, p. 226.

- Bielfeld & Hooper 1770, p. 244.

- Bielfeld & Hooper 1770, p. 345.

- Teuffel 1873, p. 385, "Public life became extinct, all political business passed into the hands of the monarch..."

- Teuffel (1870) p. 526.

- Teuffel 1870, p. 530.

- Teuffel & Schwabe 1892, pp. 4–5.

- Cruttwell 1877, p. 6.

- Cruttwell 1877, p. 341.

- Teuffel & Schwabe 1892, p. 192.

- Auerbach, Erich; Mannheim, Ralph (Translator) (1965) [1958]. Literary Language and its Public in Late Latin Antiquity and in the Middle Ages. Bollingen Series LXXIV. Pantheon Books. p. 33.

- Sandys, John Edwin (1921). A Companion to Latin Studies Edited for the Syndics of the University Press (3rd ed.). Cambridge: University Press. pp. 824–26.

- Suetonius, Claudius, 24.1.

General sources

- Bielfeld, Baron (1770), The Elements of Universal Erudition, Containing an Analytical Abridgement of the Science, Polite Arts and Belles Lettres, III, translated by Hooper, W., London: G Scott

- Citroni, Mario (2006), "The Concept of the Classical and the Canons of Model Authors in Roman Literature", in Porter, James I. (ed.), The Classical Tradition of Greece and Rome, translated by Packham, RA, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, pp. 204–34

- Cruttwell, Charles Thomas (1877), A History of Roman Literature from the Earliest Period to the Death of Marcus Aurelius, London: Charles Griffin & Co.

- Littlefield, George Emery (1904), Early Schools and School-books of New England, Boston, MA: Club of Odd Volumes

- Settis, Salvatore (2006), The Future of the "Classical", translated by Cameron, Allan, Cambridge, UK; Malden, MA: Polity Press

- Teuffel, Wilhelm Sigismund (1873), A History of Roman Literature, translated by Wagner, Wilhelm, London: George Bell & Sons

- Teuffel, Wilhelm Sigismund; Schwabe, Ludwig (1892), Teuffel's History of Roman Literature Revised and Enlarged, II, The Imperial Period, translated by Warr, George C.W. (from the 5th German ed.), London: George Bell & Sons

Further reading

| Library resources about Classical Latin |

- Allen, William Sidney. 1978. Vox Latina: A Guide to the Pronunciation of Classical Latin. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cruttwell, Charles Thomas (2005) [1877]. A History of Roman Literature from the Earliest Period to the Death of Marcus Aurelius. London: Charles Griffin and Company, Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- Dickey, Eleanor. 2012. "How to Say 'Please' in Classical Latin". The Classical Quarterly 62, no. 2: 731–48. doi:10.1017/S0009838812000286.

- Getty, Robert J. 1963. "Classical Latin meter and prosody, 1935–1962". Lustrum 8: 104–60.

- Levene, David. 1997. "God and man in the Classical Latin panegyric". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 43: 66–103.

- Lovric, Michelle, and Nikiforos Doxiadis Mardas. 1998. How to Insult, Abuse & Insinuate In Classical Latin. London: Ebury Press.

- Rosén, Hannah. 1999. Latine Loqui: Trends and Directions In the Crystallization of Classical Latin. München: W. Fink.

- Spevak, Olga. 2010. Constituent Order In Classical Latin Prose. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

- Teuffel, W. S. (2001) [1870]. Geschichte der Römischen Literatur (in German). Leipzig: B.G. Teubner. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

External links

- The Latin Library—Public domain Latin texts

- Latin Texts at the Perseus Collection

- Greek and Roman Authors on LacusCurtius

- Classical Latin Texts at the Packard Humanities Institute

- Latin Texts at Attalus

- A collection of Latin and Greek texts at the Schola Latina