Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Wars of the Second Triumvirate between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius in 42 BC, at Philippi in Macedonia. The Second Triumvirate declared the civil war ostensibly to avenge Julius Caesar's assassination in 44 BC, but the underlying cause was a long-brewing conflict between the so-called Optimates and the so-called Populares.

| Battle of Philippi | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Liberators' civil war | |||||||||

Location of Philippi | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Second Triumvirate Supported by Ptolemaic Egypt (sent ships but too late to aid in the fighting)[1][2] |

Liberators Supported by: Parthian Empire (cavalry force)[3] | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Mark Antony Octavian |

Brutus Cassius Allienus (unknown) Serapion (retreats to Tyre) | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

53,000–108,000[4] 40,000–95,000 infantry in 19 legions[4] 13,000 cavalry[4] |

60,000–105,000[4] 40,000–85,000 infantry in 17 legions[4] 20,000 cavalry[4] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 16,000 killed (3 October) |

8,000 killed (3 October) Surrender of entire army (23 October) | ||||||||

The battle, involving up to 200,000 men in one of the largest of the Roman civil wars, consisted of two engagements in the plain west of the ancient city of Philippi. The first occurred in the first week of October; Brutus faced Octavian, and Antony's forces fought those of Cassius. The Roman armies fought poorly, with low discipline, nonexistent tactical co-ordination and amateurish lack of command experience evident in abundance with neither side able to exploit opportunities as they developed.[5][6] At first, Brutus pushed back Octavian and entered his legions' camp. However, to the south, Cassius was defeated by Antony and committed suicide after hearing a false report that Brutus had also failed. Brutus rallied Cassius's remaining troops, and both sides ordered their army to retreat to their camps with their spoils. The battle was essentially a draw but for Cassius's suicide. A second encounter, on 23 October, finished off Brutus's forces after a hard-fought battle. He committed suicide in turn, leaving the triumvirate in control of the Roman Republic.

Prelude

After the assassination of Caesar, the two main conspirators, Brutus and Cassius, also known as the Liberators and leaders of the Republicans had left Italy. They took control of all the eastern provinces from Greece to Syria and of the allied eastern kingdoms. In Rome the three main Caesarian leaders (Antony, Octavian and Lepidus), who controlled almost all the Roman army in the west, had crushed the opposition of the senate and established the second triumvirate. One of their first tasks was to destroy the Liberators’ forces, not only to get full control of the Roman world, but also to avenge Caesar's death.

The triumvirs decided that Lepidus would remain in Italy, while the two main partners of the triumvirate, Antony and Octavian, moved to northern Greece with their best troops, a total of 28 legions. They were able to ferry their army across the Adriatic and sent out a scouting force of eight legions, commanded by Norbanus and Saxa, along the Via Egnatia, with the aim of searching for the Liberators' army. Norbanus and Saxa passed the town of Philippi in eastern Macedonia and took a strong defensive position at a narrow mountain pass. Antony was following, while Octavian was delayed at Dyrrachium because of his ill-health (which would accompany him throughout the Philippi campaign). Although Antony and Octavian had been able to cross the sea with their main force, further communications with Italy were made difficult by the arrival of the Republican admiral Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus, with a large fleet of 130 ships.

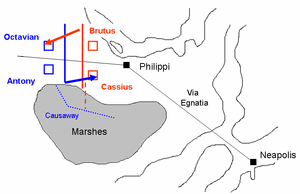

The Liberators did not wish to engage in a decisive battle, but rather to attain a good defensive position and then use their naval superiority to block the triumvirs’ communications with their supply base in Italy. They had spent the previous months plundering Greek cities to swell their war-chest. They gathered in Thrace with the Roman legions from the eastern provinces and levies from allies. With their superior forces they were able to outflank Norbanus and Saxa, who had to abandon their defensive position and retreat west of Philippi. This meant that Brutus and Cassius could position their forces to hold the high ground along both sides of the Via Egnatia, about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) west of the city of Philippi. The southern position was anchored on a supposedly impassable marsh, while on the north on impassable hills. They had time to fortify their position with a rampart and ditch. Brutus positioned his camp to the north while Cassius was on the south of the via Egnatia. Antony arrived and positioned his army south of the via Egnatia, while Octavian put his legions north of the road.

Forces

Antony and Octavian

The Triumvirs' army present for the battle included nineteen legions.[4] The sources specify the name of only one legion, IV legion, but other legions present included the III, VI, VII, VIII, X Equestris, XII, XXVI, XXVIII, XXIX, and XXX, since their veterans participated in the land settlements after the battle. Appian reports that the triumvirs’ legions were almost at full complement.[4] Furthermore, they had a large allied cavalry force of 13,000 horsemen.[4]

The liberators

The Liberators' army had seventeen legions; eight with Brutus and nine with Cassius, while two other legions were with the fleet. Only two of the legions were at full strength, but the army was reinforced by levies from the eastern allied kingdoms. Appian reports that the army mustered a total of about 80,000 foot-soldiers. Allied cavalry totaled 20,000 horsemen, including 5,000 bowmen mounted in the Eastern fashion.[4] This army included the old Caesarean legions present in the east, probably including XXVII, XXXVI, XXXVII, XXXI and XXXIII legions; so most of these legionaries were Caesarean veterans. However, at least the XXXVI legion consisted of old Pompeian veterans, enrolled in Caesar's army after the Battle of Pharsalus. The loyalty of the soldiers who were supposed to fight against Caesar's heir was a delicate issue for the Liberators. It is important to emphasize that the name "Octavian" was never used by contemporaries: he was simply known as Gaius Iulius Caesar. Cassius tried to reinforce the soldiers’ loyalty both with strong speeches ("Let it give no one any concern that he has been one of Caesar's soldiers. We were not his soldiers then, but our country's") and with a gift of 1,500 denarii for each legionary and 7,500 for each centurion.

Although ancient sources do not report the total numbers of men of the two armies, it seems that they had a similar strength. Adrian Goldsworthy suggests that at full strength the 19 Triumvir legions may have amounted to 95,000 men and the 17 Liberators' legions to 85,000.[4] Most likely each side had only 40,000–50,000 legionaries.[7] As the campaign lasted for months, it is unlikely that either side could have sustained the logistics to keep so many men, horses and baggage animals fed if both sides had had 100,000 or so troops.[4]

First battle

Antony offered battle several times, but the Liberators were not lured into leaving their defensive position.[8] Antony tried to secretly outflank the Liberators' position through the marshes in the south.[8] With great effort he was able to cut a passage through the marshes, throwing up a causeway over them.[8] This manoeuvre was finally noticed by Cassius, who countered by moving part of his army south into the marshes and constructing a transverse wall in a bid to cut off Antony's outstretched right wing.[8] This brought about a general battle on 3 October 42 BC.

Antony ordered a charge against Cassius, aiming at the fortifications between Cassius's camp and the marshes.[5] At the same time, Brutus's soldiers, provoked by the triumvirs' army, rushed against Octavian’s army, without waiting for the order of attack, which was to be given with the watchword "Liberty".[5] This surprise assault had complete success: Octavian's troops were put to flight and pursued up to their camp, which was captured by Brutus's men, led by Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus.[9] Three of Octavian's legions had their standards taken, a clear sign of a rout.[9] Octavian was not found in his tent: his couch was pierced and cut to pieces.[9] Most ancient historians say that he had been warned in a dream to beware of that day, as he wrote in his memoirs. Pliny bluntly reports that Octavian went into hiding in the marsh.[9]

However, on the other side of the Via Egnatia, Antony was able to storm Cassius’ fortifications, demolishing the palisade and filling up the ditch.[5] Then he easily took Cassius's camp, which was defended by only a few men.[5] It seems that part of Cassius's army had advanced south: when these men tried to come back they were easily repulsed by Antony.[5]

Apparently the battle had ended in a draw. Cassius had lost 8,000 men, while Octavian had about 16,000 casualties. The battlefield was very large and clouds of dust made it impossible to make a clear assessment of the outcome of the battle, so both wings were ignorant of each other's fate. Cassius moved to the top of a hill, but could not see what was happening on Brutus's side. Believing that he had suffered a crushing defeat he ordered his freedman Pindarus to kill him.[9] Brutus mourned over Cassius's body, calling him "the last of the Romans". He avoided a public funeral, fearing its negative effects on the army morale.

Other sources credit the avarice of Brutus' troops as the factor that undid their definitive victory on October 3. Premature looting and gathering of treasure by Brutus's advancing forces allowed Octavian's troops to re-form their line. In Octavian's future reign as Emperor, a common battle cry became "Complete the battle once begun!"

Second battle

On the same day as the first battle, the Republican fleet was able to intercept and destroy the triumvirs' reinforcements of two legions and other troops and supplies led by Gnaeus Domitius Calvinus. The strategic position of Antony and Octavian became perilous, since the already depleted regions of Macedonia and Thessaly were unable to supply their army for long, while Brutus could easily receive supplies from the sea. The triumvirs had to send a legion south to Achaia to collect more supplies. The morale of the troops was boosted by the promise of a further 5,000 denarii for each soldier and 25,000 for each centurion.

On the other side, the Liberators’ army was left without its best strategic mind. Brutus had less military experience than Cassius and, even worse, he could not command the same respect from his allies and his soldiers, although after the battle he offered another gift of 1,000 denarii for each soldier.

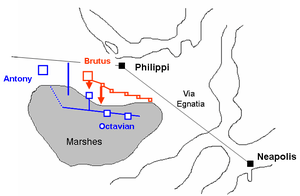

In the next three weeks, Antony was able to slowly advance his forces south of Brutus's army, fortifying a hill close to Cassius's former camp, which had been left unguarded by Brutus.

To avoid being outflanked Brutus was compelled to extend his line to the south and then the east, parallel to the Via Egnatia, building several fortified posts. While still holding the high ground he wanted to keep to the original plan of avoiding an open engagement and waiting for his naval superiority to wear out the enemy. The traditional understanding is that Brutus, against his better judgment, subsequently abandoned this strategy because his officers and soldiers were tired of the delaying tactics and demanded he offer another open battle. Brutus and his officers may have feared that their soldiers would desert to the enemy if they appeared to have lost the initiative. Plutarch also reports that Brutus had not received news of Domitius Calvinus' defeat in the Ionian Sea. When some of the eastern allies and mercenaries started deserting, Brutus was forced to attack on the afternoon of October 23. As he said, "I seem to carry on war like Pompey the Great, not so much commanding as commanded." However, the reality is that Brutus had no option but to fight, because his entire position was now in danger of being isolated and rendered untenable. If the triumvirs were allowed to continue stretching their lines unimpeded to the east they would ultimately cut off his supply route to Neapolis and pin him against the mountains. If that happened, the tables would be turned; Brutus would either be starved into submission or be forced to retreat by taking his entire army via the hazardous northern trail that had brought him to Philippi.

The battle which ensued resulted in close combat between two armies of well-trained veterans. Ranged weapons such as arrows or javelins were largely ignored; instead, the soldiers packed into solid ranks and fought face-to-face with their swords, and the slaughter was terrible. According to Cassius Dio, the two sides had little need for missile weapons, "for they did not resort to the usual manoeuvres and tactics of battles" but immediately advanced to close combat, "seeking to break each other’s ranks". In the account of Plutarch, Brutus had the better of the fight at the western end of his line and pressed hard on the triumvirs’ left wing, which gave way and retreated, being harassed by the Republican cavalry, which sought to exploit the advantage when it saw the enemy in disorder. But the eastern flank of Brutus's line had inferior numbers because it had been extended to avoid being outflanked. This meant Brutus's legions had been drawn out too thin in the center, and were so weak here they could not withstand the triumvirs’ initial charge. Having broken through, the triumvirs swung to their left to take Brutus in his flank and rear. Appian speaks of the triumvirs’ legions having "pushed back the enemy’s line as though they were turning round a very heavy machine."[6] Brutus's legions were driven back step-by-step, slowly at first, but as their ranks crumbled under the pressure they began to give ground more rapidly.[6] The second and third reserve lines in the rear failed to keep pace with the retreat and all three lines became entangled. Octavian's soldiers were able to capture the gates of Brutus's camp before the routing army could reach this defensive position. Brutus's army could not reform, which made the triumvirs’ victory complete. Brutus was able to retreat into the nearby hills with the equivalent of only four legions.[6] Seeing that surrender and capture were inevitable, Brutus committed suicide.[6]

The total casualties for the second battle of Philippi were not reported, but the close quarters fighting likely resulted in heavy losses for both sides.

Aftermath

Plutarch reports that Antony covered Brutus's body with a purple garment as a sign of respect.[6] Although they had not been close friends, he remembered that Brutus had stipulated, as a condition for his joining the plot to assassinate Caesar, that the life of Antony be spared.

Many other young Roman aristocrats lost their lives in the battle or committed suicide after the defeat, including the son of great orator Hortensius, and Marcus Porcius Cato, the son of Cato the Younger, and Marcus Livius Drusus Claudianus, the father of Livia, who became Octavian's wife.[6] Some of the nobles who were able to escape negotiated their surrender to Antony and entered his service. Among them were Lucius Calpurnius Bibulus and Marcus Valerius Messalla Corvinus. Apparently the nobles did not want to deal with the young and merciless Octavian.

The remains of the Liberators’ army were rounded up, and roughly 14,000 men were enrolled into the triumvirs' army.[6] Old veterans were discharged back to Italy, but some of the veterans remained in the town of Philippi, which became a Roman colony, Colonia Victrix Philippensium.

Antony remained in the East, while Octavian returned to Italy, with the difficult task of finding enough land on which to settle a large number of veterans. Although Sextus Pompey was controlling Sicily and Domitius Ahenobarbus still commanded the Republican fleet, the Republican resistance had been definitively crushed at Philippi.[6]

The Battle of Philippi marked the highest point of Antony's career: at that time he was the most famous Roman general and the senior partner of the Second Triumvirate.[6]

Quotes

Plutarch famously reported that Brutus experienced a vision of a ghost a few months before the battle. One night he saw a huge and shadowy form appearing in front of him; when he calmly asked, "What and whence art thou?" it answered "Thy evil spirit, Brutus: I shall see thee at Philippi." He again met the ghost the night before the battle. This episode is one of the most famous in Shakespeare’s play Julius Caesar. Plutarch also reports the last words of Brutus, quoted by a Greek tragedy "O wretched Virtue, thou wert but a name, and yet I worshipped thee as real indeed; but now, it seems, thou were but fortune's slave."

Augustus's own version of the Battle of Philippi was: "I sent into exile the murderers of my father, punishing their crimes with lawful tribunals, and afterwards, when they made war upon the Republic, I twice defeated them in battle." Qui parentem meum [interfecer]un[t eo]s in exilium expuli iudiciis legitimis ultus eorum [fa]cin[us, e]t postea bellum inferentis rei publicae vici b[is a]cie. Res Gestae 2.

Popular culture

The battle figures in Shakespeare's Julius Caesar (background of the story in Acts 4 and 5), in which the two battles are merged into a single day's events. After Cassius' death Brutus says "Tis three o'clock, and, Romans, yet ere night / We shall try fortune in a second fight." Otherwise the information is mostly accurate.

A fictionalised account of the battle is depicted in the sixth episode of the second season of the HBO television series Rome. There is but a single battle and both Cassius and Brutus fall in battle instead of being suicides, though Brutus's death is a lone, suicidal attack on the triumvirate's' advancing forces.

Citations

- Roller (2010), p. 75.

- Burstein (2004), pp. 22–23.

- Bivar, H.D.H (1968). William Bayne Fisher; Ilya Gershevitch; Ehsan Yarshater; R. N. Frye; J. A. Boyle; Peter Jackson; Laurence Lockhart; Peter Avery; Gavin Hambly; Charles Melville (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Cambridge University Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-521-20092-X.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 252.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 257.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 259.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 253.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 255.

- Goldsworthy 2010, p. 258.

See also

References

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2010). Antony and Cleopatra. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978 0 297 86104 1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas Harbottle, Dictionary of Battles. New York 1906

- Ronald Syme. The Roman revolution. Oxford 1939

- Lawrence Keppie. The making of the Roman army. New York 1984

- Sheppard, Si (2008). Philippi 42 BC: The death of the Roman Republic. Oxford: Osprey Publishing (published 2008-08-10). ISBN 978-1-84603-265-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Primary sources

- Appian: Roman Civil Wars

- Plutarch: The Life of Brutus

- Suetonius: The Life of Augustus

- Velleius Paterculus: Roman History

- Augustus: Res Gestae

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Philippi. |

- Philippi from the Greek Ministry of Culture

- Map of the First Battle of Philippi and Map of the Second Battle of Philippi at Livius.org