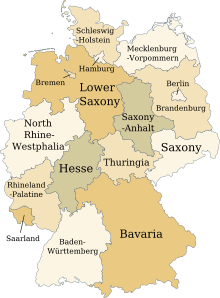

North Rhine-Westphalia

North Rhine-Westphalia (German: Nordrhein-Westfalen, pronounced [ˌnɔʁtʁaɪ̯n vɛstˈfaːlən] (![]()

![]()

North Rhine-Westphalia Nordrhein-Westfalen | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 51°28′N 7°33′E | |

| Country | Germany |

| Largest city | Cologne |

| Founded | 23 August 1946 |

| Capital | Düsseldorf |

| Government | |

| • Body | Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia |

| • Minister-President | Armin Laschet (CDU) |

| • Governing parties | CDU / FDP |

| Area | |

| • Total | 34,084.13 km2 (13,159.96 sq mi) |

| Population (2017-12-31) | |

| • Total | 17,912,134 |

| • Density | 530/km2 (1,400/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | North Rhine-Westphalian (English) Nordrhein-Westfälisch (German) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | DE-NW |

| GRP (nominal) | €711 billion (2019)[1] · 1st |

| GRP per capita | €40,000 (2019) · 7th |

| NUTS Region | DEA |

| HDI (2018) | 0.936[2] very high · 7th of 16 |

| Website | land |

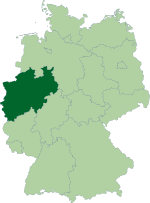

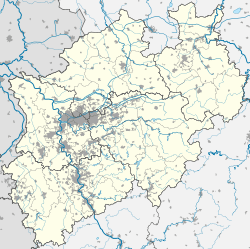

North Rhine-Westphalia is located in western Germany covering an area of 34,084 square kilometres (13,160 sq mi), which makes it the fourth-largest state. Apart from the city-states it is also the most densely populated German state. NRW has a population of 17.9 million and features 30 of the 81 German municipalities with over 100,000 inhabitants, including Cologne (over 1 million), the state capital Düsseldorf, Dortmund and Essen (all about 600.000 inhabitants) and other cities predominantly located in the Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan area, the largest urban area in Germany and the third-largest on the European continent. The location of the Rhine-Ruhr at the heart of the European Blue Banana makes it well connected to other major European cities and metropolitan areas like the Randstad, the Flemish Diamond and the Frankfurt Rhine Main Region.

North Rhine-Westphalia was established in 1946 after World War II from the Prussian provinces of Westphalia and the northern part of Rhine Province (North Rhine), and the Free State of Lippe by the British military administration in Allied-occupied Germany and became a state of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1949. The city of Bonn served as the federal capital until the reunification of Germany in 1990 and as the seat of government until 1999.

Culturally, North Rhine-Westphalia is not a uniform area; there are significant differences, especially in traditional customs, between the Rhineland region on the one hand and the regions of Westphalia and Lippe on the other. The state has always been Germany’s powerhouse with the largest economy among the German states by GDP figures.[3]

History

Creation of the state

The state of North Rhine-Westphalia was established by the British military administration's "Operation Marriage" on 23 August 1946, by merging the province of Westphalia and the northern parts of the Rhine Province, both being political divisions of the former state of Prussia within the German Reich.[4][5] On 21 January 1947, the former state of Lippe was merged with North Rhine-Westphalia.[4] The constitution of North Rhine-Westphalia was then ratified through a referendum.

Rhineland

The first written account of the area was by its conqueror, Julius Caesar, the territories west of the Rhine were occupied by the Eburones and east of the Rhine he reported the Ubii (across from Cologne) and the Sugambri to their north. The Ubii and some other Germanic tribes such as the Cugerni were later settled on the west side of the Rhine in the Roman province of Germania Inferior. Julius Caesar conquered the tribes on the left bank, and Augustus established numerous fortified posts on the Rhine, but the Romans never succeeded in gaining a firm footing on the right bank, where the Sugambri neighboured several other tribes including the Tencteri and Usipetes. North of the Sigambri and the Rhine region were the Bructeri.

As the power of the Roman empire declined, many of these tribes came to be seen collectively as Ripuarian Franks and they pushed forward along both banks of the Rhine, and by the end of the fifth century had conquered all the lands that had formerly been under Roman influence. By the eighth century, the Frankish dominion was firmly established in western Germany and northern Gaul, but at the same time, to the north, Westphalia was being taken over by Saxons pushing south.

The Merovingian and Carolingian Franks eventually built an empire which controlled first their Ripuarian kin, and then the Saxons. On the division of the Carolingian Empire at the Treaty of Verdun, the part of the province to the east of the river fell to East Francia, while that to the west remained with the kingdom of Lotharingia.[6]

By the time of Otto I (d. 973), both banks of the Rhine had become part of the Holy Roman Empire, and the Rhenish territory was divided between the duchies of Upper Lorraine on the Moselle and Lower Lorraine on the Meuse. The Ottonian dynasty had both Saxon and Frankish ancestry.

As the central power of the Holy Roman Emperor weakened, the Rhineland split into numerous small, independent, separate vicissitudes and special chronicles. The old Lotharingian divisions became obsolete, although the name survives for example in Lorraine in France, and throughout the Middle Ages and even into modern times, the nobility of these areas often sought to preserve the idea of a preeminent duke within Lotharingia, something claimed by the Dukes of Limburg, and the Dukes of Brabant. Such struggles as the War of the Limburg Succession therefore continued to create military and political links between what is now Rhineland-Westphalia and neighbouring Belgium and the Netherlands.

In spite of its dismembered condition and the sufferings it underwent at the hands of its French neighbours in various periods of warfare, the Rhenish territory prospered greatly and stood in the foremost rank of German culture and progress. Aachen was the place of coronation of the German emperors, and the ecclesiastical principalities of the Rhine bulked largely in German history.[6]

Prussia first set foot on the Rhine in 1609 by the occupation of the Duchy of Cleves and about a century later Upper Guelders and Moers also became Prussian. At the peace of Basel in 1795, the whole of the left bank of the Rhine was resigned to France, and in 1806, the Rhenish princes all joined the Confederation of the Rhine.

After the Congress of Vienna, Prussia was awarded the entire Rhineland, which included the Grand Duchy of Berg, the ecclesiastic electorates of Trier and Cologne, the free cities of Aachen and Cologne, and nearly a hundred small lordships and abbeys. The Prussian Rhine province was formed in 1822 and Prussia had the tact to leave them in undisturbed possession of the liberal institutions to which they had become accustomed under the republican rule of the French.[6] In 1920, the districts of Eupen and Malmedy were transferred to Belgium (see German-speaking Community of Belgium).

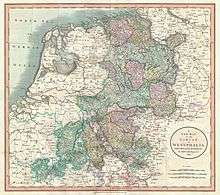

Westphalia

Around AD 1, numerous incursions occurred through Westphalia and perhaps even some permanent Roman or Romanized settlements. The Battle of Teutoburg Forest took place near Osnabrück and some of the Germanic tribes who fought at this battle came from the area of Westphalia. Charlemagne is thought to have spent considerable time in Paderborn and nearby parts. His Saxon Wars also partly took place in what is thought of as Westphalia today. Popular legends link his adversary Widukind to places near Detmold, Bielefeld, Lemgo, Osnabrück, and other places in Westphalia. Widukind was buried in Enger, which is also a subject of a legend.

Along with Eastphalia and Engern, Westphalia (Westfalahi) was originally a district of the Duchy of Saxony. In 1180, Westphalia was elevated to the rank of a duchy by Emperor Barbarossa. The Duchy of Westphalia comprised only a small area south of the Lippe River.

.jpg)

Parts of Westphalia came under Brandenburg-Prussian control during the 17th and 18th centuries, but most of it remained divided duchies and other feudal areas of power. The Peace of Westphalia of 1648, signed in Münster and Osnabrück, ended the Thirty Years' War. The concept of nation-state sovereignty resulting from the treaty became known as "Westphalian sovereignty".

As a result of the Protestant Reformation, there is no dominant religion in Westphalia. Roman Catholicism and Lutheranism are on relatively equal footing. Lutheranism is strong in the eastern and northern parts with numerous free churches. Münster and especially Paderborn are thought of as Catholic. Osnabrück is divided almost equally between Catholicism and Protestantism.

After the defeat of the Prussian Army at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, the Treaty of Tilsit in 1807 made the Westphalian territories part of the Kingdom of Westphalia from 1807 to 1813. It was founded by Napoleon and was a French vassal state. This state only shared the name with the historical region; it contained only a relatively small part of Westphalia, consisting instead mostly of Hessian and Eastphalian regions.

After the Congress of Vienna, the Kingdom of Prussia received a large amount of territory in the Westphalian region and created the province of Westphalia in 1815. The northernmost portions of the former kingdom, including the town of Osnabrück, had become part of the states of Hanover and Oldenburg.

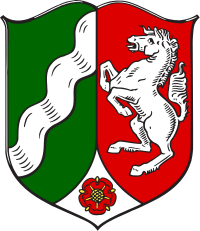

Flags and coat of arms

The flag of North Rhine-Westphalia is green-white-red with the combined coats of arms of the Rhineland (white line before green background, symbolizing the river Rhine), Westfalen (the white horse) and Lippe (the red rose). After the establishment of North Rhine-Westphalia in 1946, the tricolor was first introduced in 1948, but was not formally adopted until 1953.[7] The plain variant of the tricolor is considered the civil flag and state ensign, while government authorities use the state flag (Landesdienstflagge) which is defaced with the state's coat of arms.[7] The state ensign can easily be mistaken for a distressed flag of Hungary, as well as the former national flag of Iran (1964–1980). The same flag was used by the Rhenish Republic (1923–1924) as a symbol of independence and freedom.

According to legend, the horse in the Westphalian coat of arms is the horse that the Saxon leader Widukind rode after his baptism. Other theories attribute the horse to Henry the Lion. Some connect it with the Germanic rulers Hengist and Horsa.

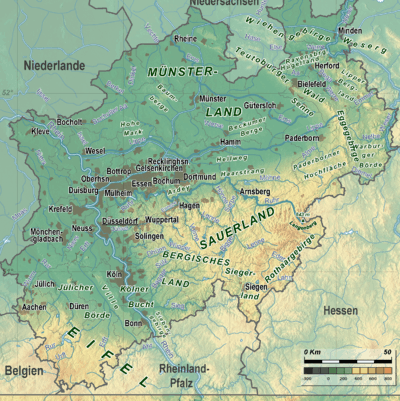

Geography

North Rhine-Westphalia encompasses the plains of the Lower Rhine region and parts of the Central Uplands (die Mittelgebirge) up to the gorge of Porta Westfalica. The state covers an area of 34,083 km2 (13,160 sq mi) and shares borders with Belgium (Wallonia) in the southwest and the Netherlands (Limburg, Gelderland and Overijssel) in the west and northwest. It has borders with the German states of Lower Saxony to the north and northeast, Rhineland-Palatinate to the south and Hesse to the southeast.

Approximately half of the state is located in the relative low-lying terrain of the Westphalian Lowland and the Rhineland, both extending broadly into the North German Plain. A few isolated hill ranges are located within these lowlands, among them the Hohe Mark, the Beckum Hills, the Baumberge and the Stemmer Berge.

The terrain rises towards the south and in the east of the state into parts of Germany's Central Uplands. These hill ranges are the Weser Uplands – including the Egge Hills, the Wiehen Hills, the Wesergebirge and the Teutoburg Forest in the east, the Sauerland, the Bergisches Land, the Siegerland and the Siebengebirge in the south, as well as the left-Rhenish Eifel in the southwest of the state. The Rothaargebirge in the border region with Hesse rises to height of about 800 m above sea level. The highest of these mountains are the Langenberg, at 843.2 m above sea level, the Kahler Asten (840.7 m) and the Clemensberg (839.2 m).

The planimetrically-determined centre of North Rhine-Westphalia is located in the south of Dortmund-Aplerbeck in the Aplerbecker Mark (51° 28' N, 7° 33' Ö). Its westernmost point is situated near Selfkant close to the Dutch border, the easternmost near Höxter on the Weser. The southernmost point lies near Hellenthal in the Eifel region. The northernmost point is the NRW-Nordpunkt near Rahden in the northeast of the state. The Nordpunkt has located the only 100 km to the south of the North Sea coast. The deepest natural dip is arranged in the district Zyfflich in the city of Kranenburg with 9.2 m above sea level in the northwest of the state. Though, the deepest point overground results from mining. The open-pit Hambach reaches at Niederzier a deep of 293 m below sea level. At the same time, this is the deepest man-made dip in Germany.

The most important rivers flowing at least partially through North Rhine-Westphalia include: the Rhine, the Ruhr, the Ems, the Lippe, and the Weser. The Rhine is by far the most important river in North Rhine-Westphalia: it enters the state as Middle Rhine near Bad Honnef, where still being part of the Mittelrhein wine region. It changes into the Lower Rhine near Bad Godesberg and leaves North Rhine-Westphalia near Emmerich at a width of 730 metres. Almost immediately after entering the Netherlands, the Rhine splits into many branches.

The Pader, which flows entirely within the city of Paderborn, is considered Germany's shortest river.

For many, North Rhine-Westphalia is synonymous with industrial areas and urban agglomerations. However, the largest part of the state is used for agriculture (almost 52%) and forests (25%).[8]

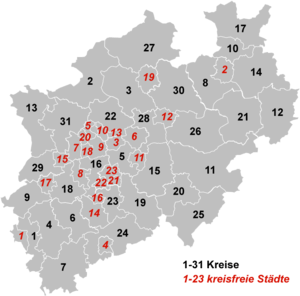

Subdivisions

The state consists of five government regions (Regierungsbezirke), divided into 31 districts (Kreise) and 23 urban districts (kreisfreie Städte). In total, North Rhine-Westphalia has 396 municipalities (1997), including the urban districts, which are municipalities by themselves. The government regions have an assembly elected by the districts and municipalities, while the Landschaftsverband has a directly elected assembly.

The five government regions of North Rhine-Westphalia each belong to one of the two Landschaftsverbände:

| Landschaftsverband Rhineland | Landschaftsverband Westfalen-Lippe |  The regional authorities Rhineland (green) and Westphalia-Lippe (red) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(Regierungsbezirke) | (Regierungsbezirke) | |||||

Regierungsbezirk Düsseldorf |

|

Regierungsbezirk Arnsberg |

| |||

Regierungsbezirk Köln |  Regierungsbezirk Detmold | |||||

Regierungsbezirk Münster | ||||||

| Rural Districts (Kreise) | Urban Districts (Kreisfreie Städte) |  |

|---|---|---|

|

Borders

The state's area covers a maximum distance of 291 km from north to south, and 266 km from east to west. The total length of the state's borders is 1,645 km. The following countries and states have a border with North Rhine-Westphalia:[9]

- Belgium (99 km)

- Netherlands (387 km)

- Lower Saxony (583 km)

- Hesse (269 km)

- Rhineland-Palatinate (307 km)

Demographics

North Rhine-Westphalia has a population of approximately 17.5 million inhabitants (more than the entire former East Germany, and slightly more than the Netherlands) and is centred around the polycentric Rhine-Ruhr metropolitan region, which includes the industrial Ruhr region with the largest city of Dortmund and the Rhenish cities of Bonn, Cologne and Düsseldorf. 30 of the 80 largest cities in Germany are located within North Rhine-Westphalia. The state's capital is Düsseldorf; the state's largest city is Cologne. In 2015, there were 160,478 births and 204,373 deaths. The TRF reached 1.52 (2015) and was highest in Lippe (1.72) and lowest in Bochum (1.29).

| Significant foreign resident populations[10] | |

| Nationality | Population (31.12.2018) |

|---|---|

| 495,245 | |

| 220,890 | |

| 206,240 | |

| 143,140 | |

| 128,820 | |

| 101,065 | |

| 80,845 | |

| 76,060 | |

| 70,340 | |

| 54,080 | |

The following table shows the ten largest cities of North Rhine-Westphalia:

| Pos. | Name | Pop. 2017 | Area (km²) | Pop. per km2 | Map |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cologne | 1,080,394 | 405.15 | 2,668 |  |

| 2 | Düsseldorf | 617,280 | 217.01 | 2,839 | |

| 3 | Dortmund | 586,600 | 280.37 | 2,090 | |

| 4 | Essen | 583,393 | 210.38 | 2,774 | |

| 5 | Duisburg | 498,110 | 232.81 | 2,140 | |

| 6 | Bochum | 365,529 | 145.43 | 2,509 | |

| 7 | Wuppertal | 353,590 | 168.37 | 2,100 | |

| 8 | Bielefeld | 332,552 | 257.83 | 1,285 | |

| 9 | Bonn | 325,490 | 141.22 | 2,307 | |

| 10 | Münster | 313,559 | 302.91 | 1,034 |

Historical population

The following table shows the population of the state since 1930. The values until 1960 are the average of the yearly population, from 1965 the population at year end is used.

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: [11] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vital statistics

- Births from January–September 2016 =

- Births from January–September 2017 =

- Deaths from January–September 2016 =

- Deaths from January–September 2017 =

- Natural growth from January–September 2016 =

- Natural growth from January–September 2017 =

Religion

As of 2018, 37.7% of the population of the state adhered to the Roman Catholic Church, 24.0% to the Evangelical Church in Germany and 38.4% of the population is irreligious or adheres to other religions.[13]

North Rhine-Westphalia ranks first in population among German states for both Roman Catholics and Protestants.

In 2016, the interior ministry of North Rhine-Westphalia reported that the number of mosques with a salafist influence had risen from 30 to 55, which indicated both an actual increase and improved reporting.[14] According to German authorities, Salafism is incompatible with the principles codified in the Constitution of Germany, in particular, democracy, the rule of law and a political order based on human rights.[15]

Politics

The politics of North Rhine-Westphalia takes place within a framework of a federal parliamentary representative democratic republic. The two main parties are, as on the federal level, the centre-right Christian Democratic Union and the centre-left Social Democratic Party. From 1966 to 2005, North Rhine-Westphalia was continuously governed by the Social Democrats or SPD-led governments.

The state's legislative body is the Landtag ("state diet").[16] It may pass laws within the competency of the state, e.g. cultural matters, the education system, matters of internal security, i.e. the police, building supervision, health supervision and the media; as opposed to matters that are reserved to Federal law.[16]

North Rhine-Westphalia uses the same electoral system as the Federal level in Germany: "Personalized proportional representation". Every five years the citizens of North Rhine-Westphalia vote in a general election to elect at least 181 members of the Landtag. Only parties who win at least 5% of the votes cast may be represented in parliament.[16]

The Landtag, the parliamentary parties and groups consisting of at least 7 members of parliament have the right to table legal proposals to the Landtag for deliberation.[16] The law that is passed by the Landtag is delivered to the Minister-President, who, together with the ministers involved, is required to sign it and announce it in the Law and Ordinance Gazette.[16]

List of Ministers-President

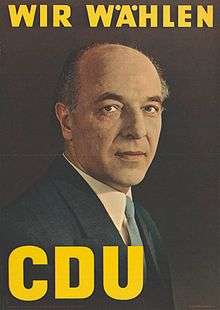

These are the Ministers-president of the Federal State of North-Rhine Westphalia:

| Ministers-president of North Rhine-Westphalia | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Name | Image | Born-Died | Party affiliation | Start of Tenure | End of Tenure |

| 1 | Rudolf Amelunxen |  |

1888–1969 | Centre Party | 1946 | 1947 |

| 2 | Karl Arnold |  |

1901–1958 | CDU | 1947 | 1956 |

| 3 | Fritz Steinhoff |  |

1897–1969 | SPD | 1956 | 1958 |

| 4 | Franz Meyers |  |

1908–2002 | CDU | 1958 | 1966 |

| 5 | Heinz Kühn |  |

1912–1992 | SPD | 1966 | 1978 |

| 6 | Johannes Rau |  |

1931–2006 | SPD | 1978 | 1998 |

| 7 | Wolfgang Clement |  |

*1940 | SPD | 1998 | 2002 |

| 8 | Peer Steinbrück | .jpg) |

*1947 | SPD | 2002 | 2005 |

| 9 | Jürgen Rüttgers |  |

*1951 | CDU | 2005 | 2010 |

| 10 | Hannelore Kraft |  |

*1961 | SPD | 2010 | 2017 |

| 11 | Armin Laschet |  |

*1961 | CDU | 2017 | incumbent |

For the current state government, see Cabinet Laschet.

Latest election results

CDU became the largest party, whereas the ruling SPD and Greens lost votes. The Pirates were ousted from the Landtag, whereas the AfD gained parliamentary representation. FDP got their best result in history. Die Linke narrowly failed to get parliamentary representation. Voter turnout was higher than in the previous election.

< 2012 ![]()

| Party | Popular vote | Seats | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | % | +/– | Seats | +/– | ||||||

| Christian Democratic Union Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands – CDU|| 2,796,683 | 33.0 | 72 | ||||||||

| Social Democratic Party of Germany Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands – SPD|| 2,649,205 | 31.2 | 69 | ||||||||

| Free Democratic Party Freie Demokratische Partei – FDP|| 1,065,307 | 12.6 | 28 | ||||||||

| Alternative for Germany Alternative für Deutschland – AfD|| 626,756 | 7.4 | 16 | ||||||||

| Alliance '90/The Greens Bündnis 90/Die Grünen|| 539,062 | 6.4 | 14 | ||||||||

| The Left Die Linke|| 415,936 | 4.9 | – | – | |||||||

| Pirate Party Piratenpartei Deutschland|| 80,780 | 1.0 | – | ||||||||

| Valid votes | 8,487,373 | 99.0% | ||||||||

| Invalid votes | 89,808 | 1.0% | ||||||||

| Totals and voter turnout | 8,577,221 | 65.2% | 199 | |||||||

| Electorate | 13,164,887 | 100.00 | — | |||||||

| Source: Die Landeswahlleiterin des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen | ||||||||||

Protection for possible nuclear disasters

Although there are no nuclear reactors located inside the state, the reactors in Tihange, Belgium are near the German border. People in the Netherlands and Germany are concerned about their safety given the age of these reactors. Billions of iodine tablets were ordered to protect the population in case of a serious nuclear accident in Tihange. In 2015 the German government extended the availability of iodine tablets: now all pregnant women, nursing mothers, and minors in the state will be eligible. Tablets will also be available for those living less than 100 km from the Tihange reactors and younger than 45 years of age.[17]

Culture

Architecture and building monuments

The state is not known for its castles like other regions in Germany.[18] However, North Rhine-Westphalia has a high concentration of museums, cultural centres, concert halls and theatres.[18]

Historic monuments

.jpg) Medieval architecture in Aachen

Medieval architecture in Aachen.jpg)

- Reinoldikirche and Alter Markt in Dortmund

The Historical City Hall in Münster

The Historical City Hall in Münster Timber framing in Monschau

Timber framing in Monschau.jpg) Schloss Nordkirchen

Schloss Nordkirchen

Modern architecture

The Zeche Zollern in Dortmund

The Zeche Zollern in Dortmund

The Langen Foundation in Neuss

The Langen Foundation in Neuss The Schwebebahn in Wuppertal

The Schwebebahn in Wuppertal

World Heritage Sites

The state has Aachen Cathedral, the Cologne Cathedral, the Zeche Zollverein in Essen, the Augustusburg Palace in Brühl and the Imperial Abbey of Corvey in Höxter which are all World Heritage Sites.[18]

The Imperial Abbey of Corvey

The Imperial Abbey of Corvey

Cuisine

| Pumpernickel bread one of the most famous German breads. It's made from a dark rye, and has a unique and subtly sweet flavor. This bread has been baked for centuries and has acquired its popular name from the war era, when bread was being rationed. It means flatulence and bad spirits.[19][20] |  |

Drinks

- Kölsch is a local beer speciality brewed in Cologne.

- Alt is a local beer speciality brewed in Düsseldorf and the Lower Rhine Region.

- Dortmunder Export is a local pale lager beer speciality brewed in Dortmund.

Festivals

North Rhine-Westphalia hosts film festivals in Cologne, Bonn, Dortmund, Duisburg, Münster, Oberhausen and Lünen.[18]

Other large festivals include Rhenish carnivals, Ruhrtriennale.

Every year GamesCom is hosted in Cologne. It is the largest video game convention in Europe.

Music

- The composer Ludwig van Beethoven was born in Bonn in 1770.

- A regional anthem is the Lied für NRW (Song for NRW).

- North Rhine-Westphalia is home to many of Germany's best-known heavy metal, speed metal and thrash metal bands: Accept, Angel Dust, Blind Guardian, Doro (formerly of Warlock), Grave Digger, Holy Moses, Kreator, Rage, Scanner and Sodom. Also, North Rhine-Westphalia is home to Kraftwerk, originally a Krautrock band for four years, then later a synth-pop band.

Economy

In the 1950s and 1960s, Westphalia was known as Land von Kohle und Stahl or the land of coal and steel. In the post-World War II recovery, the Ruhr was one of the most important industrial regions in Europe, and contributed to the German Wirtschaftswunder. As of the late 1960s, repeated crises led to contractions of these industrial branches. On the other hand, producing sectors, particularly in mechanical engineering and metal and iron working industry, experienced substantial growth. Despite this structural change and an economic growth which was under national average, the 2018 GDP of 705 billion euro (1/4 of the total German GDP) made NRW the economically strongest state of Germany, as well as one of the most important economical areas in the world.[21] Of Germany's top 100 corporations, 37 are based in North Rhine-Westphalia. On a per capita base, however, North Rhine-Westphalia remains one of the weaker among the Western German states.[22]

North Rhine-Westphalia attracts companies from both Germany and abroad. In 2009, the state had the most foreign direct investments (FDI) anywhere in Germany.[23] Around 13,100 foreign companies from the most important investment countries control their German or European operations from bases in North Rhine-Westphalia.

There have been many changes in the state's economy in recent times. Among the many changes in the economy, employment in the creative industries is up while the mining sector is employing fewer people.[18] Industrial heritage sites are now workplaces for designers, artists and the advertising industry.[18][24] The Ruhr region has – since the 1960s – undergone a significant structural change away from coal mining and steel industry. Many rural parts of Eastern Westphalia, Bergisches Land and the Lower Rhine ground their economy on "Hidden Champions" in various sectors.

As of June 2014, the unemployment rate is 8.2%, second highest among all western German states.[25] In October 2018 the unemployment rate stood at 6.4% and was higher than the national average.[26]

| Year[27] | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate in % | 9.2 | 8.8 | 9.2 | 10.0 | 10.2 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 8.9 | 8.7 | 8.1 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 8.2 | 8.0 | 7.7 | 7.4 | 6.8 |

Transport

With its central location in the most important European economic area, high population density, strong urbanization and numerous business locations, North Rhine-Westphalia has one of the densest transport networks in the world.

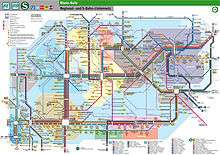

Regional Rail network

The regional rail network is organised around the main in towns in Rhein-Ruhr: Bonn, Cologne, Wuppertal, [Düsseldorf]]Essen and Dortmund. Some public transport companies in this region are run under the umbrella of the Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr, which provides a uniform ticket system valid for the entire area. The Ruhr region is well-integrated into the national rail system, the Deutsche Bahn, for both passenger and goods services, each city in the region has at least one or more train stations. The bigger central stations have hourly direct connections to the bigger European cities as Amsterdam, Brussels, Paris, Vienna or Zürich.

The Rhein-Ruhr area also contains the longest tram system in the world, with tram and Stadtbahn services from Witten to Krefeld as well as the Rhine-Ruhr S-Bahn network. Originally the system was even bigger, it was possible to travel from Unna to Bad Honnef without using railway or bus services.

As of 2012, the VRR network consists of 978 lines,[28] of which there are:

- in regional rail transit

- 11 S-Bahn lines[28] (see: Rhine-Ruhr S-Bahn)

- 15 RegionalExpress lines[28] (see: List of regional railway lines in North Rhine-Westphalia)

- 24 RegionalBahn lines[28] (see: List of regional railway lines in North Rhine-Westphalia)

- in local rail transit

- 19 Stadtbahn light rail lines[28] (see: Rhine-Ruhr Stadtbahn)

- 45 streetcar (Straßenbahn) lines[28]

- 1 Schwebebahn line[28] (in Wuppertal)

- 2 H-Bahn peoplemover systems[28] made up of three lines (two H-Bahn lines in Dortmund, and the Düsseldorf SkyTrain at Düsseldorf airport)

- in bus transit

- 906 bus lines,[28] including

- 33 express bus lines (Schnellbus, SB)

- 18 semi-fast bus lines (CityExpress, CE)

- 6 trolleybus lines[28] (in Solingen)

- 906 bus lines,[28] including

- 15,300 km of route network[29] (bus, light rail, and train)

- 11,500 transit stops

Road

North Rhine-Westphalia has the densest network of Autobahns in Germany and similar Schnellstraßen (expressways). The Autobahn network is built in a grid network, with four east–west (A2, A40, A42, A44) and seven north–south (A1, A3, A43, A45, A52, A57, A59) routes. The A1, A2 and A3 are mostly used by through traffic, while the other autobahns have a more regional function.

Both the A44 and the A52 have several missing links, in various stages of planning. Some missing sections are currently in construction or planned to be constructed in the near future.

Additional expressways serve as bypasses and local routes, especially around Dortmund and Bochum. Due to the density of the autobahns and expressways, Bundesstraßen are less important for intercity traffic. The first Autobahns in the Region opened during the mid-1930s. Due to the density of the network, and the number of alternative routes, traffic volumes are generally lower than other major metropolitan areas in Europe. Traffic congestion is an everyday occurrence, but far less so than in the Randstad in the Netherlands, another polycentric urban area. Most important Autobahns have six lanes.

Airports

The region benefits from the presence of several airport infrastructure. The main airport is Düsseldorf Airport, world class, which hosts 24.5 million passengers per year and offers flights to many destinations.Düsseldorf is the third largest airport in Germany after Frankfurt and Munich;[30] It is a hub for Eurowings and a focus city for several more airlines. The airport has three passenger terminals and two runways and can handle wide-body aircraft up to the Airbus A380.[31]

The second airport is the international airport of Germany's fourth-largest city Cologne, and also serves Bonn, former capital of West Germany. With around 12.4 million passengers passing through it in 2017, it is the seventh-largest passenger airport in Germany and the third-largest in terms of cargo operations. By traffic units, which combines cargo and passengers, the airport is in fifth position in Germany.[32] As of March 2015, Cologne Bonn Airport had services to 115 passenger destinations in 35 countries.[33] It is named after Konrad Adenauer, a Cologne native and the first post-war Chancellor of West Germany.

Third airport in the region, Dortmund Airport is a minor international airport located 10 km (6.2 mi) east[34] of Dortmund. It serves the eastern Rhine-Ruhr area, the largest urban agglomeration in Germany, and is mainly used for low-cost and leisure charter flights. In 2019 the airport served 2,719,563 passengers.

Then the airport of Münsterland Münster Osnabrück International Airport, hosting nearly 986,260 passengers per year and Airport Weeze with 693,404 passengers.

Waterways

The Rhine flows through North Rhine-Westphalia. Its banks are usually heavily populated and industrialized, in particular the agglomerations Cologne, Düsseldorf and Ruhr area. Here the Rhine flows through the largest conurbation in Germany, the Rhine-Ruhr region. Duisburg Inner Harbour (Duisport) and Dortmund Port are large industrial inland ports and serve as hubs along the Rhine and the German inland water transport system. The country is crossed by many canals like Rhine–Herne Canal (RHK), der Wesel-Datteln-Kanal (WDK), der Datteln-Hamm-Kanal (DHK) and Dortmund-Ems-Kanal (DEK) an important role for inland navigation.

Education

RWTH Aachen is one of Germany's leading universities of technology and was chosen by DFG as one of the German Universities of Excellence in 2007 and again in 2012.

North Rhine-Westphalia is home to 14 universities and over 50 partly postgraduate colleges, with a total of over 500,000 students.[35] Largest and oldest university is the University of Cologne (Universität zu Köln), founded in 1388 AD, since 2012 also one of Germany's eleven Universities of Excellence. University of Duisburg-Essen (Universität Duisburg-Essen), is also well known and is one of the largest universities in Germany.

Sports

Football

NRW is home to several football clubs of the Bundesliga including Arminia Bielefeld, Bayer 04 Leverkusen, Borussia Dortmund, Borussia Mönchengladbach, FC Schalke 04, 1. FC Köln and the 2. Bundesliga including Fortuna Düsseldorf, VfL Bochum and SC Paderborn 07. Since the formal establishment of the German Bundesliga in 1963, Borussia Dortmund and Borussia Mönchengladbach have been the most successful teams with both winning 5 titles. FC Köln won 2 titles, including the very first in 1963. Before the league's establishment, North Rhine-Westfalian teams competed for the title of Deutscher Fußballmeister (German Football Champion). Here, FC Schalke 04 brought home 7 titles, while Dortmund and Köln won an additional 3 and 1 title(s), respectively. Fortuna Düsseldorf and Rot-Weiß Essen have each been German Champion once. North Rhine-Westphalia has been a very successful footballing state having a combined total of 25 championships, fewer only than Bavaria.

Other divisions:

- Alemannia Aachen

- Rot-Weiß Oberhausen

- Rot-Weiß Essen

- Fortuna Köln

- MSV Duisburg

- Sportfreunde Siegen

- Wuppertaler SV

Ice hockey

North Rhine-Westphalia is home to DEL teams Düsseldorfer EG, Kölner Haie, Krefeld Pinguine, and Iserlohn Roosters.

See also

- Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen

- Kunststiftung NRW

- NRW Forum

- Outline of Germany

- List of rivers of North Rhine-Westphalia

- List of lakes in North Rhine-Westphalia

References

- "GDP NRW official statistics". Retrieved 17 February 2019.

- "Sub-national HDI – Area Database – Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Campbell, Eric. "Germany – German Powerhouse". NRW. Retrieved June 2020. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help) - "History of North Rhine-Westphalia". Government of North Rhine-Westphalia. Retrieved 10 April 2011.

- Wagener, Volker (18 November 2009). "North Rhine-Westphalia: an overview". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Government of North Rhine-Westphalia (10 March 1953). "Gesetz über die Landesfarben, das Landeswappen und die Landesflagge" (in German). Archived from the original on 12 March 2005. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- Tatsachen über Deutschland (2003) Nordrhein-Westfalen, p. 44

- Length of borders taken from Statistisches Jahrbuch NRW 2005, 47. Jahrgang, Landesamt für Datenverarbeitung und Statistik Nordrhein-Westfalen, p. 22

- 31 December 2014 German Statistical Office. Zensus 2014: Bevölkerung am 31. Dezember 2014

- "Bevölkerung NRW". Landesdatenbank Nordrhein-Westfalen. Landesbetrieb für Information und Technik Nordrhein-Westfalen. Retrieved 26 August 2010.

Zahlen sind Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes. Die Zahlen ab 1965 beziehen sich auf die Bevölkerung zum 31. Dezember des jeweiligen Jahres. Bis 1960 Mittlere Jahresbevölkerung. Bis einschließlich 1986 geschätzte Werte. Die Fortschreibung des Bevölkerungsstandes basiert ab 1987 auf den Ergebnissen der Volkszählung von 1987. Daten vor 1977 wurden auf den Gebietsstand 1. Juli 1976 umgerechnet

- "Bevölkerung". Statistische Ämter des Bundes Und der Länder. Retrieved 16 June 2018.

- Evangelische Kirche in Deutschland – Kirchemitgliederzahlen Stand 31. Dezember 2018 EKD, January 2020

- ONLINE, RP. "Verfassungsschutz: Salafisten agitieren in NRW in 55 Moscheen". RP ONLINE (in German). Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- "Salafismus". www.verfassungsschutz.bayern.de (in German). Retrieved 22 July 2018.

- "The Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia". Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

- AD.NL (8 August 2016)(Dutch)German State fears nuclear disaster

- "Culture". State of North Rhine-Westphalia. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Weichselbaum, Dr. Elizabeth (2009). "Synthesis Report No 6: Traditional Foods in Europe" (PDF). European Food Information Resource (EuroFIR).

- "The history of Pumpernickel Bread". www.kitchenproject.com. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- Ministerium für Wirtschaft, Mittelstand und Energie des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen: Konjunkturindikatoren NRW Archived 13 August 2007 at Archive.today

- Arbeitskreis Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen der Länder: Volkswirtschaftliche Gesamtrechnungen der Länder Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- the Online Editor. "FDI". New European Economy. Archived from the original on 4 October 2011. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- Staff, Reporter. "Opening times of shops in Germany". www.oeffnungszeiten.com (in German). oeffnungszeiten. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Statistik der Bundesagentur für Arbeit". statistik.arbeitsagentur.de. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- "Arbeitslosenquote nach Bundesländern in Deutschland 2018 | Statista". Statista (in German). Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- (Destatis), © Statistisches Bundesamt (13 November 2018). "Federal Statistical Office Germany – GENESIS-Online". www-genesis.destatis.de. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "Verbundbericht 2012/2013 als Blätterkatalog" [Network Report 2012/2013 as a Page-by-page Catalog] (in German). Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr (VRR). p. 107. Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr – Homepage – Welcome to the VRR". Verkehrsverbund Rhein-Ruhr (VRR). Retrieved 23 October 2013.

- "ADV passenger statistics and aircraft movements". Archived from the original on 30 November 2010.

- "Flughafen Düsseldorf schließt Bauarbeiten für A380 ab". Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 6 January 2016.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Sommerflugplan 2015: Sieben neue Ziele ab Flughafen Köln/Bonn". airliners.de. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "innovation.nrw.de: students in NRW by university or college, 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 29 October 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to North Rhine-Westphalia. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for North Rhine-Westphalia. |

- Official Government Portal

- The Landtag of North Rhine-Westphalia

- Holidays in NRW

- Information and resources on the history of Westphalia on the Web portal "Westphalian History"

- Guidelines for the integration of the Land Lippe within the territory of the federal state North-Rhine-Westphalia of 17 January 1947

- North Rhine-Westphalia images from Cologne and Duesseldorf to Paderborn and Muenster

.jpg)