Kuwait

Kuwait (/kʊˈweɪt/ (![]()

![]()

State of Kuwait دولة الكويت (Arabic) Dawlat al-Kuwait | |

|---|---|

Anthem: an-Nashīd al-Waṭani National Anthem | |

Location of Kuwait (green) | |

| Capital and largest city | Kuwait City 29°22′N 47°58′E |

| Official languages | Arabic |

| Ethnic groups | [1] |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Kuwaiti |

| Government | Unitary constitutional monarchy[2], with near-absolute political domination by the Sabah family |

• Emir | Sabah Ahmad al-Sabah |

• Prime Minister | Sabah Khalid al-Sabah |

| Marzouq Ali al-Ghanim | |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Establishment | |

• Independence from the Emirate of Al Hasa | 1752 |

| 1913 | |

• End of treaties with the United Kingdom | 19 June 1961 |

| Area | |

• Total | 17,818 km2 (6,880 sq mi) (152nd) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2019 estimate | 4,420,110 |

• 2005 census | 2,213,403[3] |

• Density | 200.2/km2 (518.5/sq mi) (61st) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2020 estimate |

• Total | $303 billion[4] (57th) |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2018 estimate |

• Total | $118.271 billion[4] (57th) |

• Per capita | $28,199[4] (23rd) |

| HDI (2018) | very high · 57th |

| Currency | Kuwaiti dinar (KWD) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (AST) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy (CE) |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +965 |

| ISO 3166 code | KW |

| Internet TLD | .kw |

Website www.e.gov.kw | |

| |

Oil reserves were discovered in commercial quantities in 1938. In 1946, crude oil was exported for the first time.[10][11] From 1946 to 1982, the country underwent large-scale modernization. In the 1980s, Kuwait experienced a period of geopolitical instability and an economic crisis following the stock market crash. In 1990, Kuwait was invaded, and later annexed, by Saddam's Iraq. The Iraqi occupation of Kuwait came to an end in 1991 after military intervention by a military coalition led by the United States. Kuwait is a non-NATO ally of the United States.[12] Kuwait is also a major ally of ASEAN, while maintaining a very strong relationship with China.[13][14][15]

Kuwait is a constitutional sovereign state with a semi-democratic political system. Kuwait has a high-income economy backed by the world's sixth largest oil reserves. The Kuwaiti dinar is the highest valued currency in the world.[16] According to the World Bank, the country has the nineteenth highest per capita income.[17] The Constitution was promulgated in 1962.[18][19][20] Kuwait is home to the largest opera house in the Middle East. The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[21]

History

Early history

In 1613, the town of Kuwait was founded in modern-day Kuwait City. Administratively, it was a sheikhdom, ruled by local sheikhs.[22][23] In 1716, the Bani Utub settled in Kuwait, which at this time was inhabited by a few fishermen and primarily functioned as a fishing village.[24] In the eighteenth century, Kuwait prospered and rapidly became the principal commercial center for the transit of goods between India, Muscat, Baghdad and Arabia.[25][26] By the mid 1700s, Kuwait had already established itself as the major trading route from the Persian Gulf to Aleppo.[27]

During the Persian siege of Basra in 1775–79, Iraqi merchants took refuge in Kuwait and were partly instrumental in the expansion of Kuwait's boat-building and trading activities.[28] As a result, Kuwait's maritime commerce boomed,[28] as the Indian trade routes with Baghdad, Aleppo, Smyrna and Constantinople were diverted to Kuwait during this time.[27][29] The East India Company was diverted to Kuwait in 1792.[30] The East India Company secured the sea routes between Kuwait, India and the east coasts of Africa.[30] After the Persians withdrew from Basra in 1779, Kuwait continued to attract trade away from Basra.[31]

Kuwait was the center of boat building in the Persian Gulf region.[32][33] During the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, vessels made in Kuwait carried the bulk of trade between the ports of India, East Africa and the Red Sea.[34][35][36] Kuwaiti ships were renowned throughout the Indian Ocean. Regional geopolitical turbulence helped foster economic prosperity in Kuwait in the second half of the 18th century.[37] Perhaps the biggest catalyst for much of Kuwait becoming prosperous was due to Basra's instability in the late 18th century.[38] In the late 18th century, Kuwait partly functioned as a haven for Basra's merchants, who were fleeing Ottoman government persecution.[39] Kuwaitis developed a reputation as the best sailors in the Persian Gulf.[40][41]

British Protectorate (1899–1961)

In the 1890s, Kuwait was threatened by the Ottoman Empire. In a bid to address its security issues, the then ruler, Sheikh Mubarak Al Sabah signed an agreement with the British government in India, subsequently known as the Anglo-Kuwaiti Agreement of 1899 and became a British protectorate. This gave Britain exclusivity of access and trade with Kuwait, and excluded Iraq to the north from a port on the Persian Gulf. The Sheikhdom of Kuwait remained a British protectorate from 1899 (until 1961).[22][23]

Following the Kuwait–Najd War of 1919–20, Ibn Saud imposed a trade blockade against Kuwait from the years 1923 until 1937.[42] The goal of the Saudi economic and military attacks on Kuwait was to annex as much of Kuwait's territory as possible. At the Uqair conference in 1922, the boundaries of Kuwait and Najd were set; as a result of British interference, Kuwait had no representative at the Uqair conference. Ibn Saud persuaded Sir Percy Cox to give him two-thirds of Kuwait's territory. More than half of Kuwait was lost due to Uqair. After the Uqair conference, Kuwait was still subjected to a Saudi economic blockade and intermittent Saudi raiding.

The Great Depression harmed Kuwait's economy, starting in the late 1920s.[42] International trading was one of Kuwait's main sources of income before oil.[42] Kuwaiti merchants were mostly intermediary merchants.[42] As a result of the decline of European demand for goods from India and Africa, Kuwait's economy suffered. The decline in international trade resulted in an increase in gold smuggling by Kuwaiti ships to India.[42] Some Kuwaiti merchant families became rich from this smuggling.[43] Kuwait's pearl industry also collapsed as a result of the worldwide economic depression.[43] At its height, Kuwait's pearl industry had led the world's luxury market, regularly sending out between 750 and 800 ships to meet the European elite's desire for pearls.[43] During the economic depression, luxuries like pearls were in little demand.[43] The Japanese invention of cultured pearls also contributed to the collapse of Kuwait's pearl industry.[43]

Historian Hanna Batatu explains how the British threatened to take the Kurdish area and Mosul out of Iraq provided that King Faisal granted Britain control of the oil in the region. In 1938 the Kuwaiti Legislative Council[44] unanimously approved a request for Kuwait's reintegration with Iraq. A year later an armed uprising which had raised the integration banner as its objective was put down by the British.[45]

1962–1982: Golden Era

With the end of the world war, and increasing need for oil across the world, Kuwait experienced a period of prosperity driven by oil and its liberal atmosphere. The period of 1946-82 is often termed "the golden period of Kuwait" by western academics.[46][47][48] In popular discourse, the years between 1946 and 1982 are referred to as the "Golden Era".[46][47][48][49] However, Kuwaiti academics argue that this period was marked by benefits accruing only to the wealthier and connected ruling classes. It saw an increased presence of British, American and French citizens connected with the new oil industry, wealth transfer to people connected with the Emir, the creation of a new privileged upper class of educated Kuwaitis, bankers, and a vast majority of Kuwaitis living a life of penury. This resulted in a growing gulf between the wealthy minority and the majority of common citizens.[22] In 1950, a major public-work programme began to enable Kuwaitis to enjoy a modern standard of living. By 1952, the country became the largest oil exporter in the Persian Gulf region. This massive growth attracted many foreign workers, especially from Palestine, India, and Egypt – with the latter being particularly political within the context of the Arab Cold War.[50] In June 1961, Kuwait became independent with the end of the British protectorate and the Sheikh Abdullah Al-Salim Al-Sabah became Emir of Kuwait. Kuwait's national day, however, is celebrated on 25 February, the anniversary of the coronation of Sheikh Abdullah (it was originally celebrated on 19 June, the date of independence, but concerns over the summer heat caused the government to move it).[51] Under the terms of the newly drafted Constitution, Kuwait held its first parliamentary elections in 1963. Kuwait was the first of the Arab states of the Persian Gulf to establish a constitution and parliament.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Kuwait was considered by some as the most developed country in the region.[52][53][54] Kuwait was the pioneer in the Middle East in diversifying its earnings away from oil exports.[55] The Kuwait Investment Authority is the world's first sovereign wealth fund. From the 1970s onward, Kuwait scored highest of all Arab countries on the Human Development Index.[54] Kuwait University was established in 1966.[54] Kuwait's theatre industry was well known throughout the Arab world.[46][54] However, it also began to see the growth of plush gated properties, wherein the interiors resembled western villas and the streets were filled with roads marked with potholes.[22]

In the 1960s and 1970s, Kuwait's press was described as one of the freest in the world.[56] Kuwait was the pioneer in the literary renaissance in the Arab region.[57] In 1958, Al-Arabi magazine was first published. The magazine went on to become the most popular magazine in the Arab world.[57] Many Arab writers moved to Kuwait because they enjoyed greater freedom of expression than elsewhere in the Arab world.[58][59] The Iraqi poet Ahmed Matar left Iraq in the 1970s to take refuge in the more liberal environment of Kuwait.

Kuwaiti society embraced liberal and Western attitudes throughout the 1960s and 1970s.[60] For example, most Kuwaiti women did not wear the hijab in the 1960s and 70s.[61][62]

1982 to present

In the early 1980s, Kuwait experienced a major economic crisis after the Souk Al-Manakh stock market crash and decrease in oil price.[64]

During the Iran–Iraq War, Kuwait supported Iraq. Throughout the 1980s, there were several terror attacks in Kuwait, including the 1983 Kuwait bombings, hijacking of several Kuwait Airways planes and the attempted assassination of Emir Jaber in 1985. Kuwait was a regional hub of science and technology in the 1960s and 1970s up until the early 1980s; the scientific research sector significantly suffered due to the terror attacks.[65]

After the Iran–Iraq War ended, Kuwait declined an Iraqi request to forgive its US$65 billion debt.[66] An economic rivalry between the two countries ensued after Kuwait increased its oil production by 40 percent.[67] Tensions between the two countries increased further in July 1990, after Iraq complained to OPEC claiming that Kuwait was stealing its oil from a field near the border by slant drilling of the Rumaila field.[67]

In August 1990, Iraqi forces invaded and annexed Kuwait. After a series of failed diplomatic negotiations, the United States led a coalition to remove the Iraqi forces from Kuwait, in what became known as the Gulf War. On 26 February 1991, the coalition succeeded in driving out the Iraqi forces. As they retreated, Iraqi forces carried out a scorched earth policy by setting oil wells on fire.[68] During the Iraqi occupation, more than 1,000 Kuwaiti civilians were killed. In addition, more than 600 Kuwaitis went missing during Iraq's occupation;[69] remains of approximately 375 were found in mass graves in Iraq.

In March 2003, Kuwait became the springboard for the US-led invasion of Iraq. Upon the death of the Emir Jaber in January 2006, Saad Al-Sabah succeeded him but was removed nine days later by the Kuwaiti parliament due to his ailing health. Sabah Al-Sabah was sworn in as Emir.

From 2001 to 2009, Kuwait had the highest Human Development Index ranking in the Arab world.[70][71][72][73] In 2005, women won the right to vote and run in elections. In 2014 and 2015, Kuwait was ranked first among Arab countries in the Global Gender Gap Report.[74][75][76] Sabah Al Ahmad Sea City was inaugurated in mid 2015.[77][78]

The Amiri Diwan is currently developing the new Kuwait National Cultural District (KNCD), which comprises Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Cultural Centre, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre, Al Shaheed Park, and Al Salam Palace.[79][80] With a capital cost of more than US$1 billion, the project is one of the largest cultural investments in the world.[79] In November 2016, the Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre opened.[63][81] It is the largest cultural centre in the Middle East.[82][83] The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[21] In 2016 Kuwait commenced a new national development plan, Kuwait Vision 2035, including plans to diversify the economy and become less dependent on oil.[84]

Culture

Kuwaiti popular culture, in the form of theatre, radio, music, and television soap opera, flourishes and is even exported to neighboring states.[85][86] Within the Gulf Arab states, the culture of Kuwait is the closest to the culture of Bahrain and southern Iraq; this is evident in the close association between the two states in theatrical productions and soap operas.[87]

Society

Kuwaiti society is markedly more open than other Gulf Arab societies.[88] Kuwaiti citizens are ethnically diverse, consisting of both Arabs and Persians ('Ajam).[89] Kuwait stands out in the region as the most liberal in empowering women in the public sphere.[90][91][92] Kuwaiti women outnumber men in the workforce.[93] Kuwaiti political scientist Ghanim Alnajjar sees these qualities as a manifestation of Kuwaiti society as a whole, whereby in the Gulf Arab region it is "the least strict about traditions".[94]

Television and theatre

_version.jpg)

Kuwait's television drama industry tops other Gulf Arab drama industries and produces a minimum of fifteen serials annually.[95][96][97] Kuwait is the production centre of the Gulf television drama and comedy scene.[96] Most Gulf television drama and comedy productions are filmed in Kuwait.[96][98][99] Kuwaiti soap operas are the most-watched soap operas from the Gulf region.[95][100][101] Soap operas are most popular during the time of Ramadan, when families gather to break their fast.[102] Although usually performed in the Kuwaiti dialect, they have been shown with success as far away as Tunisia.[103] Kuwait is frequently dubbed the "Hollywood of the Gulf" due to the popularity of its television soap operas and theatre.[104]

Kuwait is known for its home-grown tradition of theatre.[105][106][107] Kuwait is the only country in the Gulf Arab region with a theatrical tradition.[105] The theatrical movement in Kuwait constitutes a major part of the country's cultural life.[108] Theatrical activities in Kuwait began in the 1920s when the first spoken dramas were released.[109] Theatre activities are still popular today.[108] Abdulhussain Abdulredha is the most prominent actor.

Kuwait is the main centre of scenographic and theatrical training in the Gulf region.[110][111] In 1973, the Higher Institute of Theatrical Arts was founded by the government to provide higher education in theatrical arts.[111] The institute has several divisions. Many actors have graduated from the institute, such as Souad Abdullah, Mohammed Khalifa, Mansour Al-Mansour, along with a number of prominent critics such as Ismail Fahd Ismail.

Theatre in Kuwait is subsidized by the government, previously by the Ministry of Social Affairs and now by the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Letters (NCCAL).[112] Every urban district has a public theatre.[113] The public theatre in Salmiya is named after Abdulhussain Abdulredha.

Arts

Kuwait has the oldest modern arts movement in the Arabian Peninsula.[114][115][116] Beginning in 1936, Kuwait was the first Gulf Arab country to grant scholarships in the arts.[114] The Kuwaiti artist Mojeb al-Dousari was the earliest recognized visual artist in the Gulf Arab region.[117] He is regarded as the founder of portrait art in the region.[118] The Sultan Gallery was the first professional Arab art gallery in the Gulf.[119][120]

Kuwait is home to more than 30 art galleries.[121][122] In recent years, Kuwait's contemporary art scene has boomed.[123][124][125] Khalifa Al-Qattan was the first artist to hold a solo exhibition in Kuwait. He founded a new art theory in the early 1960s known as "circulism".[126][127] Other notable Kuwaiti artists include Sami Mohammad, Thuraya Al-Baqsami and Suzan Bushnaq.

The government organizes various arts festivals, including the Al Qurain Cultural Festival and Formative Arts Festival.[128][129][130] The Kuwait International Biennial was inaugurated in 1967,[131] more than 20 Arab and foreign countries have participated in the biennial.[131] Prominent participants include Layla Al-Attar. In 2004, the Al Kharafi Biennial for Contemporary Arab Art was inaugurated.

Music

Kuwait is the birthplace of various popular musical genres, such as sawt.[132] Kuwaiti music has considerably influenced the music culture in other Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries.[133][132] Traditional Kuwaiti music is a reflection of the country's seafaring heritage,[134] which is known for genres such as fijiri.[135][136][137] Kuwait pioneered contemporary Khaliji music.[138][139][140] Kuwaitis were the first commercial recording artists in the Gulf region.[138][139][140] The first known Kuwaiti recordings were made between 1912 and 1915.[141]

The Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Cultural Centre contains the largest opera house in the Middle East.[142] Kuwait is home to various music festivals, including the International Music Festival hosted by the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters (NCCAL).[143][144] Kuwait has several academic institutions specializing in university-level music education.[145][146][147] The Higher Institute of Musical Arts was established by the government to provide bachelor's degrees in music.[145][146][147] In addition, the College of Basic Education offers bachelor's degrees in music education.[145][146][147] The Institute of Musical Studies offers degrees equivalent to secondary school.[145][147][146]

Literature

Kuwait has, in recent years, produced several prominent contemporary writers such as Ismail Fahd Ismail, author of over twenty novels and numerous short story collections.[148] There is also evidence that Kuwaiti literature has long been interactive with English and French literature.[149]

Museums

The new Kuwait National Cultural District (KNCD) consists of various cultural venues including Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Cultural Centre, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre, Al Shaheed Park, and Al Salam Palace.[79][80] With a capital cost of more than US$1 billion, it is one of the largest cultural districts in the world.[79] The Abdullah Salem Cultural Centre is the largest museum complex in the Middle East.[150][151] The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[21]

Several Kuwaiti museums are devoted to Islamic art, most notably the Tareq Rajab Museums and Dar al Athar al Islamiyyah cultural centres.[152][153] The Dar al Athar al Islamiyyah cultural centres include education wings, conservation labs, and research libraries.[154][155][156] There are several art libraries in Kuwait.[157][156][158] Khalifa Al-Qattan's Mirror House is the most popular art museum in Kuwait.[159] Many museums in Kuwait are private enterprises.[160][152] In contrast to the top-down approach in other Gulf states, museum development in Kuwait reflects a greater sense of civic identity and demonstrates the strength of civil society in Kuwait, which has produced many independent cultural enterprises.[161][152][160]

Sadu House is among Kuwait's most important cultural institutions. Bait Al-Othman is the largest museum specializing in Kuwait's history. The Scientific Center is one of the largest science museums in the Middle East. The Museum of Modern Art showcases the history of modern art in Kuwait and the region.[162] The National Museum, established in 1983, has been described as "underused and overlooked".[163]

Sport

Football is the most popular sport in Kuwait. The Kuwait Football Association (KFA) is the governing body of football in Kuwait. The KFA organises the men's, women's, and futsal national teams. The Kuwaiti Premier League is the top league of Kuwaiti football, featuring eighteen teams. The Kuwait national football team have been the champions of the 1980 AFC Asian Cup, runners-up of the 1976 AFC Asian Cup, and have taken third place of the 1984 AFC Asian Cup. Kuwait has also been to one FIFA World Cup, in 1982; they drew 1–1 with Czechoslovakia before losing to France and England, failing to advance from the first round. Kuwait is home to many football clubs including Al-Arabi, Al-Fahaheel, Al-Jahra, Al-Kuwait, Al-Naser, Al-Salmiya, Al-Shabab, Al Qadsia, Al-Yarmouk, Kazma, Khaitan, Sulaibikhat, Sahel, and Tadamon. The biggest football rivalry in Kuwait is between Al-Arabi and Al Qadsia.

Basketball is one of the country's most popular sports. The Kuwait national basketball team is governed by the Kuwait Basketball Association (KBA). Kuwait made its international debut in 1959. The national team has been to the FIBA Asian Championship in basketball eleven times. The Kuwaiti Division I Basketball League is the highest professional basketball league in Kuwait. Cricket in Kuwait is governed by the Kuwait Cricket Association. Other growing sports include rugby union. Handball is widely considered to be the national icon of Kuwait, although football is more popular among the overall population.

Ice hockey in Kuwait is governed by the Kuwait Ice Hockey Association. Kuwait first joined the International Ice Hockey Federation in 1985, but was expelled in 1992 due to a lack of ice hockey activity.[164] Kuwait was re-admitted into the IIHF in May 2009.[165] In 2015, Kuwait won the IIHF Challenge Cup of Asia.[166][167]

Media

Kuwait's media is annually classified as "partly free" in the Freedom of Press survey by Freedom House.[168] Since 2005,[169] Kuwait has frequently earned the highest ranking of all Arab countries in the annual Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders.[170][171][172][173][174][175][176][177][178] In 2009, 2011, 2013 and 2014, Kuwait surpassed Israel as the country with the greatest press freedom in the Middle East.[170][171][172][173][177] Kuwait is also frequently ranked as the Arab country with the greatest press freedom in Freedom House's annual Freedom of Press survey.[179][180][181][182][183][184][185]

Kuwait produces more newspapers and magazines per capita than its neighbors.[186][187] There are limits to Kuwait's press freedom; while criticism of the government and ruling family members is permitted, Kuwait's constitution criminalizes criticism of the Emir.

The state-owned Kuwait News Agency (KUNA) is the largest media house in the country. The Ministry of Information regulates the media industry in Kuwait.

Kuwait has 15 satellite television channels, of which four are controlled by the Ministry of Information. State-owned Kuwait Television (KTV) offered first colored broadcast in 1974 and operates five television channels. Government-funded Radio Kuwait also offers daily informative programming in several foreign languages including Arabic, Farsi, Urdu, and English on the AM and SW.

Politics

Kuwait is a constitutional emirate with a semi-democratic political system.[20][188][189] The Emir is the head of state. The hybrid political system is divided between an elected parliament and appointed government.[190][191]

The Constitution of Kuwait was promulgated in 1962. Kuwait is among the Middle East's freest countries in civil liberties and political rights.[192] Freedom House rates the country as "Partly Free" in the Freedom in the World survey.[193]

Political culture

The Constitution of Kuwait is considered a liberal constitution in the GCC.[194] It guarantees a wide range of civil liberties and rights. In contrast to other states in the region, the political process largely respects constitutional provisions. Kuwait has a robust public sphere and active civil society with political and social organizations that are parties in all but name.[195][196] Professional groups like the Chamber of Commerce maintain their autonomy from the government.[195][196]

The National Assembly is the legislature and has oversight authority. The National Assembly consists of fifty elected members, who are chosen in elections held every four years. Since the parliament can conduct inquiries into government actions and pass motions of no confidence, checks and balances are robust in Kuwait.[197] The parliament can be dissolved under a set of conditions based on constitutional provisions.[198] The Constitutional Court and Emir both have the power to dissolve the parliament, although the Constitutional Court can invalidate the Emir's dissolution.

Executive power is executed by the government. The Emir appoints the prime minister, who in turn chooses the ministers comprising the government. According to the constitution, at least one minister has to be an elected MP from the parliament. The parliament is often rigorous in holding the government accountable, government ministers are frequently interpellated and forced to resign.[198][197] Kuwait has more government accountability and transparency than other GCC countries.[195]

The judiciary is nominally independent of the executive and the legislature, and the Constitutional Court is charged with ruling on the conformity of laws and decrees with the constitution.[198] The judiciary's independence has come under question, although the Constitutional Court is widely regarded as one of the most judicially independent courts in the Arab world.[199] The Constitutional Court has the power to dissolve the parliament and invalidate the Emir's decrees, as happened in 2013 when the dissolved 2009 parliament resumed its role.

Kuwaiti women outnumber men in the workforce.[93] The political participation of Kuwaiti women has been limited,[200] although Kuwaiti women are among the most emancipated women in the Middle East. In 2014 and 2015, Kuwait was ranked first among Arab countries in the Global Gender Gap Report.[74][75][76] In 2013, 53% of Kuwaiti women participated in the labor force.[201] Kuwait has higher female citizen participation in the workforce than other GCC countries.[93][201][202]

Political groups and parliamentary voting blocs exist, although most candidates run as independents. Once elected, many deputies form voting blocs in the National Assembly. Kuwaiti law does not recognize political parties.[203] However, numerous political groups function as de facto political parties in elections, and there are blocs in the parliament. Major de facto political parties include the National Democratic Alliance, Popular Action Bloc, Hadas (Kuwaiti Muslim Brotherhood), National Islamic Alliance and the Justice and Peace Alliance.

Legal system

Kuwait follows the "civil law system" modeled after the French legal system,[204][205][206] Kuwait's legal system is largely secular.[207][208][209][210] Sharia law governs only family law for Muslim residents,[208][211] while non-Muslims in Kuwait have a secular family law. For the application of family law, there are three separate court sections: Sunni, Shia, and non-Muslim. According to the United Nations, Kuwait's legal system is a mix of English common law, French civil law, Egyptian civil law and Islamic law.[212]

The court system in Kuwait is secular.[213][214] Unlike other Arab states of the Persian Gulf, Kuwait does not have Sharia courts.[214] Sections of the civil court system administer family law.[214] Kuwait has the most secular commercial law in the Gulf.[215] The parliament criminalized alcohol consumption in 1983.[216] Kuwait's Code of Personal Status was promulgated in 1984.[217]

Human rights

Human rights in Kuwait has been the subject of criticism, particularly regarding foreign workers' rights. Expatriates account for 70% of Kuwait's total population. The kafala system leaves foreign workers prone to exploitation. Kuwait has the most liberal labor laws in the GCC.[218][219] As a result, the International Labour Organization (ILO) removed Kuwait from the list of countries violating workers rights.[220] Male homosexuality is illegal in Kuwait and punishable by up to 6 years in prison.[221]

Kuwaiti activist and blogger Hamad al-Naqi, who is a Kuwaiti Shi'ite, was sentenced to 10 years in prison for "blasphemous tweets" and criticizing neighboring Saudi and Bahraini monarchs.[222] Amnesty International designated al-Naqi a prisoner of conscience and called for his immediate and unconditional release.[223]

As of 2009, 20% of the youth in juvenile centres have dyslexia, as compared to the 6% of the general population.[224] Data from a 1993 study found that there is a higher rate of psychiatric morbidity in Kuwaiti prisons than in the general population.[225]

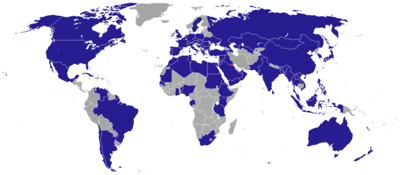

Foreign relations

Foreign affairs relations of Kuwait is handled at the level of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The first foreign affairs department bureau was established in 1961. Kuwait became the 111th member state of the United Nations in May 1963. It is a long-standing member of the Arab League and Cooperation Council for the Arab States of the Gulf.

Before the Gulf War, Kuwait was the only "pro-Soviet" state in the Persian Gulf region.[226] Kuwait acted as a conduit for the Soviets to the other Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and Kuwait was used to demonstrate the benefits of a pro-Soviet stance.[226] In July 1987, Kuwait refused to allow U.S. military bases in its territory.[227] As a result of the Gulf War, Kuwait's relations with the U.S. have improved (Major non-NATO ally) and it currently hosts thousands of US military personnel and contractors within active U.S. facilities. Kuwait is also a major ally of ASEAN and enjoys a good relationship with China while working to establish a model of cooperation in numerous fields.[15][13][14] According to Kuwaiti officials, Kuwait is the largest Arab investor in Germany, particularly with regard to the Mercedes-Benz company.[228]

Military

The Military of Kuwait traces its original roots to the Kuwaiti cavalrymen and infantrymen that used to protect Kuwait and its wall since the early 1900s. These cavalrymen and infantrymen formed the defense and security forces in metropolitan areas and were charged with protecting outposts outside the wall of Kuwait.

The Military of Kuwait consists of several joint defense forces. The governing bodies are the Kuwait Ministry of Defense, the Kuwait Ministry of Interior, the Kuwait National Guard and the Kuwait Fire Service Directorate. The Emir of Kuwait is the commander-in-chief of all defense forces by default. Even in the most adverse of times, such as a war, the military is not permitted to act without the Emir's consent.

Administrative divisions

Kuwait is divided into six governorates. The governorates are further subdivided into areas.

- Al Asimah

- Hawalli

- Farwaniya

- Mubarak Al-Kabeer

- Ahmadi

- Jahra

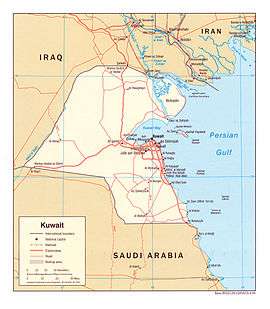

Geography

Located in the north-east corner of the Arabian Peninsula, Kuwait is one of the smallest countries in the world in terms of land area. Kuwait lies between latitudes 28° and 31° N, and longitudes 46° and 49° E. The flat, sandy Arabian Desert covers most of Kuwait. Kuwait is generally low lying, with the highest point being 306 m (1,004 ft) above sea level.[2]

Kuwait has nine islands, all of which, with the exception of Failaka Island, are uninhabited.[229] With an area of 860 km2 (330 sq mi), the Bubiyan is the largest island in Kuwait and is connected to the rest of the country by a 2,380-metre-long (7,808 ft) bridge.[230] 0.6% of Kuwaiti land area is considered arable[2] with sparse vegetation found along its 499-kilometre-long (310 mi) coastline.[2] Kuwait City is located on Kuwait Bay, a natural deep-water harbor.

Kuwait's Burgan field has a total capacity of approximately 70 billion barrels (1.1×1010 m3) of proven oil reserves. During the 1991 Kuwaiti oil fires, more than 500 oil lakes were created covering a combined surface area of about 35.7 km2 (13.8 sq mi).[231] The resulting soil contamination due to oil and soot accumulation had made eastern and south-eastern parts of Kuwait uninhabitable. Sand and oil residue had reduced large parts of the Kuwaiti desert to semi-asphalt surfaces.[232] The oil spills during the Gulf War also drastically affected Kuwait's marine resources.[233]

Climate

The spring season in March is warm with occasional thunderstorms. The frequent winds from the northwest are cold in winter and hot in summer. Southeasterly damp winds spring up between July and October. Hot and dry south winds prevail in spring and early summer. The shamal, a northwesterly wind common during June and July, causes dramatic sandstorms.[234] Summers in Kuwait are some of the hottest on earth. The highest recorded temperature was 54 °C (129 °F) at Mitribah on 21 July 2016, which is the highest temperature recorded in Asia.[235][236].

In 2014 Kuwait was the fourth highest country in the world in term of CO2 per capita emissions after Qatar, Curaçao and Trinidad and Tobago according to the World Bank.[237] On average, every single inhabitant released 25.2 metric tons of CO2 in the atmosphere that year. In comparison, the world average was 5.0 tons per capita the same year.

Access to biocapacity in Kuwait is lower than world average. In 2016, Kuwait had 0.59 global hectares [238] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[239] In 2016 Kuwait used 8.6 global hectares of biocapacity per person - their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use about 14.5 times as much biocapacity as Kuwait contains. As a result, Kuwait is running a biocapacity deficit.[238]

| Climate data for Kuwait | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 30 (86) |

36 (97) |

42 (108) |

47 (117) |

50 (122) |

53 (127) |

54 (129) |

54 (129) |

51 (124) |

47 (117) |

39 (102) |

32 (90) |

54 (129) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 21 (70) |

23 (73) |

27 (81) |

33 (91) |

40 (104) |

45 (113) |

47 (117) |

46 (115) |

44 (111) |

39 (102) |

28 (82) |

24 (75) |

35 (95) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 14.7 (58.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

22.3 (72.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

35.2 (95.4) |

37.3 (99.1) |

35.9 (96.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

27.5 (81.5) |

20.3 (68.5) |

15.5 (59.9) |

26.4 (79.4) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 9 (48) |

12 (54) |

16 (61) |

21 (70) |

27 (81) |

30 (86) |

32 (90) |

30 (86) |

27 (81) |

23 (73) |

17 (63) |

12 (54) |

21 (71) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4 (25) |

1 (34) |

9 (48) |

14 (57) |

17 (63) |

24 (75) |

25 (77) |

23 (73) |

20 (68) |

16 (61) |

10 (50) |

6 (43) |

−4 (25) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 8 (0.3) |

10 (0.4) |

6 (0.2) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

10 (0.4) |

13 (0.5) |

47 (1.8) |

| Average rainy days | 0.4 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 2.81 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 7 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 9 |

| Source 1: Weather2Travel[240] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Climate-Data.org (altitude: 13m, mean temp)[241] | |||||||||||||

National parks

At present, there are five protected areas in Kuwait recognized by the IUCN. In response to Kuwait becoming the 169th signatory of the Ramsar Convention, Bubyan island's Mubarak al-Kabeer reserve was designated as the country's first Wetland of International Importance.[242] The 50,948 ha reserve consists of small lagoons and shallow salt marshes and is important as a stop-over for migrating birds on two migration routes.[242] The reserve is home to the world's largest breeding colony of crab-plover.[242]

Biodiversity

More than 363 species of birds were recorded in Kuwait, 18 species of which breed in the country.[243] Kuwait is situated at the crossroads of several major bird migration routes and between two and three million birds pass each year.[244] The marshes in northern Kuwait and Jahra have become increasingly important as a refuge for passage migrants.[244] Kuwaiti islands are important breeding areas for four species of tern and the socotra cormorant.[244]

Kuwait's marine and littoral ecosystems contain the bulk of the country's biodiversity heritage.[244] Twenty eight species of mammal are found in Kuwait; animals such as gerboa, desert rabbits and hedgehogs are common in the desert.[244] Large carnivores, such as the wolf, caracal and jackal, are not found.[244] Among the endangered mammalian species are the red fox and wild cat.[244] Causes for wildlife extinction are habitat destruction and extensive unregulated hunting.[244] Forty reptile species have been recorded although none are endemic to Kuwait.[244]

Water and sanitation

Kuwait does not have any permanent rivers. It does have some wadis, the most notable of which is Wadi Al-Batin which forms the border between Kuwait and Iraq.

Kuwait relies on water desalination as a primary source of fresh water for drinking and domestic purposes.[245][246] There are currently more than six desalination plants.[246] Kuwait was the first country in the world to use desalination to supply water for large-scale domestic use. The history of desalination in Kuwait dates back to 1951 when the first distillation plant was commissioned.[245]

In 1965, the Kuwaiti government commissioned the Swedish engineering company of VBB (Sweco) to develop and implement a plan for a modern water-supply system for Kuwait City. The company built five groups of water towers, thirty-one towers total, designed by its chief architect Sune Lindström, called "the mushroom towers". For a sixth site, the Emir of Kuwait, Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmed, wanted a more spectacular design. This last group, known as Kuwait Towers, consists of three towers, two of which also serve as water towers.[247] Water from the desalination facility is pumped up to the tower. The thirty-three towers have a standard capacity of 102,000 cubic meters of water. "The Water Towers" (Kuwait Tower and the Kuwait Water Towers) were awarded the Aga Khan Award for Architecture (1980 Cycle).[248]

Kuwait's fresh water resources are limited to groundwater, desalinated seawater, and treated wastewater effluents.[245] There are three major municipal wastewater treatment plants.[245] Most water demand is currently satisfied through seawater desalination plants.[245][246] Sewage disposal is handled by a national sewage network that covers 98% of facilities in the country.[249]

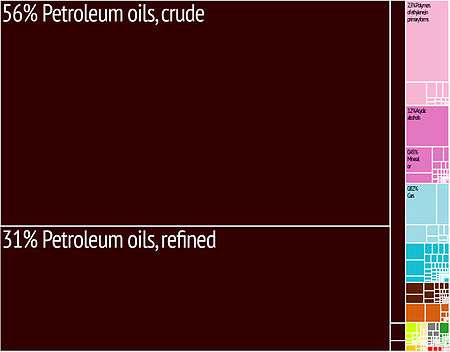

Economy

Kuwait has a petroleum-based economy, petroleum is the main export product. The Kuwaiti dinar is the highest-valued unit of currency in the world.[16] According to the World Bank, Kuwait is the seventh richest country in the world per capita.[250] Kuwait is the second richest GCC country per capita (after Qatar).[250][251][252] Petroleum accounts for half of GDP and 90% of government income.[253] Non-petroleum industries include financial services.[253]

In the past five years, there has been a significant rise in entrepreneurship and small business start-ups in Kuwait.[254][255] The informal sector is also on the rise,[256] mainly due to the popularity of Instagram businesses.[257][258][259]

Kuwait is a major source of foreign economic assistance to other states through the Kuwait Fund for Arab Economic Development, an autonomous state institution created in 1961 on the pattern of international development agencies. In 1974, the fund's lending mandate was expanded to include all developing countries in the world.

In 2018 Kuwait enacted certain measures to regulate foreign labor. Citing security concerns, workers from Georgia will be subject to heightened scrutiny when applying for entry visas, and an outright ban was being imposed on the entry of domestic workers from Guinea-Bissau and Vietnam.[260] Workers from Bangladesh are also banned.[261]

Petroleum

Despite its relatively small territory, Kuwait has proven crude oil reserves of 104 billion barrels, estimated to be 10% of the world's reserves. According to the constitution, all natural resources in the country are state property. Kuwait currently pumps 2.9 million bpd and its full production capacity is a little over 3 million bpd.

Finance

The Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA) is Kuwait's sovereign wealth fund specializing in foreign investment. The KIA is the world's oldest sovereign wealth fund. Since 1953, the Kuwaiti government has directed investments into Europe, United States and Asia Pacific. As of 2015, the holdings were valued at $592 billion in assets.[262] It is the 5th largest sovereign wealth fund in the world.

Kuwait has a leading position in the financial industry in the GCC; the abyss that separates Kuwait from its Persian Gulf neighbors in terms of tourism, transport, and other measures of diversification is absent in the financial sector.[263] The Emir has promoted the idea that Kuwait should focus its energies, in terms of economic development, on the financial industry.[263]

The historical preeminence of Kuwait (among the Persian Gulf monarchies) in finance dates back to the founding of the National Bank of Kuwait in 1952.[263] The bank was the first local publicly traded corporation in the Persian Gulf region.[263] In the late 1970s and early 1980s, an alternative stock market, trading in shares of Persian Gulf companies, emerged in Kuwait, the Souk Al-Manakh.[263] At its peak, its market capitalization was the third highest in the world, behind only the US and Japan, and ahead of the UK and France.[263]

Kuwait has a large wealth-management industry that stands out in the region.[263] Kuwaiti investment companies administer more assets than those of any other GCC country, save the much larger Saudi Arabia.[263] The Kuwait Financial Centre, in a rough calculation, estimated that Kuwaiti firms accounted for over one-third of the total assets under management in the GCC.[263] The relative strength of Kuwait in the financial industry extends to its stock market.[263] For many years, the total valuation of all companies listed on the Kuwait Stock Exchange far exceeded the value of those on any other GCC bourse, except Saudi Arabia.[263] In 2011, financial and banking companies made up more than half of the market capitalization of the Kuwaiti bourse; among all the Persian Gulf states, the market capitalization of Kuwaiti financial-sector firms was, in total, behind only that of Saudi Arabia.[263]

In recent years, Kuwaiti investment companies have invested large percentages of their assets abroad, and their foreign assets have become substantially larger than their domestic assets.[263]

Health and research

Kuwait has a state-funded healthcare system, which provides treatment without charge to Kuwaiti nationals. There are outpatient clinics in every residential area in Kuwait. A public insurance scheme exists to provide reduced cost healthcare to expatriates. Private healthcare providers also run medical facilities in the country, available to members of their insurance schemes. There are 29 public hospitals. Many new hospitals are under construction.[264] The Sheikh Jaber Al-Ahmad Hospital is the largest hospital in the Middle East.[265]

Kuwait has a growing scientific research sector. To date, Kuwait has registered 384 patents, the second highest figure in the Arab world.[266][267][268][269] Kuwait produces the largest number of patents per capita in the Arab world and OIC.[270][271][272][273] The government has implemented various programs to foster innovation resulting in patent rights.[270][274] Between 2010 and 2016, Kuwait registered the highest growth in patents in the Arab world.[270][268][274]

Technology Startups

Orbital Space

Orbital Space (Arabic: الفضاء المداري) is a Kuwaiti private company aiming to drive the establishment of space sector in Kuwait. The company was incorporated in August 2018 as the first private company in the Arab region to enable students' access to space (low earth orbits). Orbital Space initiatives were recognized by SatellitePro ME with the “SPACE INITIATIVE OF THE YEAR 2019 AWARD".[275]

Orbital Space Initiatives

Orbital Space introduced several initiatives to promote space technology among students and encourage them to take part in space activities.[276]

1. TSCK Experiment in Space

Orbital Space in collaboration the Scientific Center of Kuwait (TSCK) introduced for the first time in Kuwait the opportunity for students to send a science experiment to space. The objectives of this initiative was to allow students to learn about (a) how science space missions are done; (b) microgravity (weightlessness) environment; (c) how to do science like a real scientist. This opportunity was made possible through Orbital Space agreement with DreamUp PBC and Nanoracks LLC, which are collaborating with NASA under a Space Act Agreement.[277] The students' experiment was named "Kuwait’s Experiment: E.coli Consuming Carbon Dioxide to Combat Climate Change".[278] The experiment has been manifested on SpaceX CRS-21 (SpX-21) spaceflight to the International Space Station (ISS) on October 30th, 2020. One of the astronauts (member of the ISS Expedition 64) is expected to conduct the experiment on behalf of the students.

2. Code in Space

To increase awareness about current opportunities and to encourage solutions to challenges faced by the satellite industry, Orbital Space in collaboration with the Space Challenges Program[279] and EnduroSat[280] introduced an international online students programming opportunity called "Code in Space". This opportunity allows students from around the world to send and execute their own code in space.[281] The code is transmitted from a satellite ground station to a cubesat (nanosatellite) orbiting earth 450 km above sea level. The code is then executed by the satellite’s onboard computer and tested under real space environment conditions. The nanosatellite is called "QMR-KWT" (Arabic: قمر الكويت) which means “Moon of Kuwait”, translated from Arabic. QMR-KWT is scheduled to be launched to space in February 2021 on SpaceX Falcon 9 Block 5 rocket. It is planned to have QMR-KWT shuttled to its final destination (Sun-synchronous orbit) via Vigoride orbit transfer vehicle by Momentus Space. QMR-KWT is Kuwait's first satellite.[282]

3. Um Alaish 4

Seven years after the launch of the world's first communications satellite, Telstar 1, Kuwait inaugurated in October 1969 one of the first satellite ground stations in the Middle East about 70 km north of Kuwait City in an area called “Um Alaish”.[283] The Um Alaish satellite station complex housed several satellite ground stations including Um Alaish 1 (1969), Um Alaish 2 (1977), Um Alaish 3 (1981). It provided satellite communication services in Kuwait until 1990 when it was destroyed by the Iraqi armed forces during the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait.[284] In 2019, Orbital Space established an amateur satellite ground station to provide free access to signals from satellites in orbit passing over Kuwait. The station was named Um Alaish 4 to continue the legacy of “Um Alaish” satellite station.[285] Um Alaish 4 is member of FUNcube distributed ground station network[286] and the Satellite Networked Open Ground Station project (SatNOGS).[287]

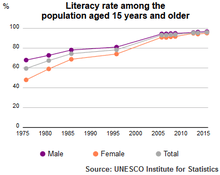

Education

Kuwait has the highest literacy rate in the Arab world.[288] The general education system consists of four levels: kindergarten (lasting for 2 years), primary (lasting for 5 years), intermediate (lasting for 4 years) and secondary (lasting for 3 years).[289] Schooling at primary and intermediate level is compulsory for all students aged 6 – 14. All the levels of state education, including higher education, are free.[290]

The public school system is undergoing a revamp due to a project in conjunction with the World Bank.[291] In 2013, the government launched a pilot project in 48 schools across the state called the National Curriculum Framework.[291] The curriculum is set to be implemented in the next two or three years.[291][292]

Tourism

Tourism accounts for 1.5 percent of the GDP.[293][294] In 2016, the tourism industry generated nearly $500 million in revenue.[295] The annual "Hala Febrayer" festival attracts many tourists from neighboring GCC countries,[296] and includes a variety of events including music concerts, parades, and carnivals.[296][297][298] The festival is a month-long commemoration of the liberation of Kuwait, and runs from 1 to 28 February. Liberation Day itself is celebrated on 26 February.[299]

The Amiri Diwan is currently developing the new Kuwait National Cultural District (KNCD), which comprises Sheikh Abdullah Al Salem Cultural Centre, Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre, Al Shaheed Park, and Al Salam Palace.[79][80] With a capital cost of more than US$1 billion, the project is one of the largest cultural investments in the world.[79] In November 2016, the Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre opened.[63] It is the largest cultural centre in the Middle East.[82] The Kuwait National Cultural District is a member of the Global Cultural Districts Network.[21]

Transport

Kuwait has an extensive and modern network of highways. Roadways extended 5,749 km (3,572 mi), of which 4,887 km (3,037 mi) is paved. There are more than two million passenger cars, and 500,000 commercial taxis, buses, and trucks in use. On major highways the maximum speed is 120 km/h (75 mph). Since there is no railway system in the country, most people travel by automobiles.

The country's public transportation network consists almost entirely of bus routes. The state owned Kuwait Public Transportation Company was established in 1962. It runs local bus routes across Kuwait as well as longer distance services to other Gulf states. The main private bus company is CityBus, which operates about 20 routes across the country. Another private bus company, Kuwait Gulf Link Public Transport Services, was started in 2006. It runs local bus routes across Kuwait and longer distance services to neighbouring Arab countries.

There are two airports in Kuwait. Kuwait International Airport serves as the principal hub for international air travel. State-owned Kuwait Airways is the largest airline in the country. A portion of the airport complex is designated as Al Mubarak Air Base, which contains the headquarters of the Kuwait Air Force, as well as the Kuwait Air Force Museum. In 2004, the first private airline of Kuwait, Jazeera Airways, was launched. In 2005, the second private airline, Wataniya Airways was founded.

Kuwait has one of the largest shipping industries in the region. The Kuwait Ports Public Authority manages and operates ports across Kuwait. The country's principal commercial seaports are Shuwaikh and Shuaiba, which handled combined cargo of 753,334 TEU in 2006.[300] Mina Al-Ahmadi, the largest port in the country, handles most of Kuwait's oil exports.[301] Construction of another major port located in Bubiyan island started in 2007. The port is expected to handle 1.3 million TEU when operations start.

Demographics

Kuwait's 2018 population was 4.6 million people, of which 1.4 million were Kuwaitis, 1.2 million are other Arabs, 1.8 million Asian expatriates,[1] and 47,227 Africans.[302]

Ethnic groups

Expatriates in Kuwait account for around 70% of Kuwait's total population. In end of December 2018, 57.65% of Kuwait's total population are Arabs (including Arab expats).[1] Indians and Egyptians are the largest expat communities respectively.[303][304]

Religion

Most Kuwaiti citizens are Muslim; it is estimated that 60%–65% are Sunni and 35%–40% are Shias.[305][306] Most Shia Kuwaiti citizens are of Persian ancestry or of Iraqi origin.[307][308][309][310][311][312][313] The country includes a native Christian community, estimated to be composed of between 259 and 400 Christian Kuwaiti citizens.[314] Kuwait is the only GCC country besides Bahrain to have a local Christian population who hold citizenship. There is also a small number of Bahá'í Kuwaiti citizens.[315][316] Kuwait also has a large community of expatriate Christians, Hindus, Buddhists, and Sikhs.[315]

Religion by Nationality in Kuwait (2018)[1]

| Nationality | Islam | % | Christian | % | Other | % | Total | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kuwaiti | 1,402,801 | 99.98% | 289 | 0.02% | 23 | 0.00% | 1,403,113 | 30.36% |

| Non-Kuwaiti Arabs | 1,183,371 | 93.84% | 69,855 | 5.54% | 7,836 | 0.62% | 1,261,062 | 27.29% |

| Asian | 814,767 | 43.61% | 725,316 | 38.83% | 328,125 | 17.56% | 1,868,208 | 40.42% |

| African | 15,991 | 33.86% | 24,679 | 52.26% | 6,557 | 13.88% | 47,227 | 1.02% |

| European | 6,553 | 36.26% | 10,352 | 57.27% | 1,170 | 6.47% | 18,076 | 0.39% |

| American & Australian | 13,577 | 56.83% | 8,995 | 37.48% | 1,360 | 5.60% | 23,892 | 0.52% |

| TOTAL | 3,437,061 | 74.36% | 839,506 | 18.17% | 345,071 | 7.47% | 4,621,638 | 100% |

Note:

– Christians from Asia in Kuwait mostly come from the Philippines, South Korea, and some from Indonesia, Malaysia, India and other countries.

– Muslims from Asia in Kuwait mostly come from Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and other countries.

– Hindus from Asia in Kuwait mostly come from India, Nepal and Sri Lanka.

– Buddhists from Asia in Kuwait mostly come from China, Thailand and Vietnam.

Languages

Kuwait's official language is Modern Standard Arabic, but its everyday usage is limited to journalism and education. Kuwaiti Arabic is the variant of Arabic used in everyday life.[317] English is widely understood and often used as a business language. Beside English, French is taught as a third language for the students of the humanities at schools, but for two years only. Kuwaiti Arabic is a variant of Gulf Arabic, sharing similarities with the dialects of neighboring coastal areas in Eastern Arabia.[318] Due to immigration during its early history as well as trade, Kuwaiti Arabic borrowed a lot of words from Persian, Indian languages, Balochi language, Turkish, English and Italian.[319]

Due to historical immigration, Kuwaiti Persian is used among Ajam Kuwaitis.[320][321][322] The Iranian sub-dialects of Larestani, Khonji, Bastaki and Gerashi also influenced the vocabulary of Kuwaiti Arabic.[323]

References

- "Nationality by Religion in Kuwait 2018". Statistic PACI. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "Kuwait". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014.

- "Population of Kuwait".

- "IMF Report for Selected Countries and Subjects : Kuwait". International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- "Human Development Report 2019" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 10 December 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Kuwait – definition of Kuwait in English". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- "Definition of Kuwait by Merriam-Webster". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- "Public Authority for Civil Information". Government of Kuwait. 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Kuwait steps up deportations of expat workers". The National. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 June 2016.

- "Wise cities" in the Mediterranean? : challenges of urban sustainability. Woertz, Eckart, Ajl, Max. Barcelona. ISBN 978-84-92511-57-0. OCLC 1117436298.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Contributors". Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East. 35 (2): 382–384. 2015. doi:10.1215/1089201x-3139815. ISSN 1089-201X.

- Associated Press. "U.S. tightens military relationship with Kuwait". nl.newsbank.com. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Times, Global. "KUNA : Kuwait calls for stronger GCC-ASEAN partnership – Politics – 28/09/2017". www.kuna.net.kw.

- "KUNA : Kuwait calls for stronger GCC-ASEAN partnership – Politics – 28/09/2017". www.kuna.net.kw.

- "China and Kuwait agree to establish strategic partnership". GBTIMES.

- "10 Most Valuable Currencies in the World". Silicon India. 21 March 2012. Archived from the original on 16 March 2015.

- "GDP per capita, PPP (current international $) | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Ibrahim Ahmed Elbadawi; Atif Abdallah Kubursi. "Kuwaiti Democracy: Illusive or Resilient?" (PDF). American University of Beirut. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Kuwait". Reporters without Borders. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Kuwait's Democracy Faces Turbulence". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 26 June 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- "Current Members – Global Cultural Districts Network". Global Cultural Districts Network.

- Al-Nakib, Farah (13 April 2016). Kuwait Transformed: A History of Oil and Urban Life. Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804798525.

- Casey, Michael (2007). The history of Kuwait - Greenwood histories of modern nations. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0313340734.

- Al-Jassar, Mohammad Khalid A. (May 2009). Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya (PhD thesis). The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-109-22934-9.

- Bell, Gawain, Sir (1983). Shadows on the Sand: The Memoirs of Sir Gawain Bell. C. Hurst. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-905838-92-2.

- "ʻAlam-i Nisvāṉ". 2 (1–2). University of Karachi. 1995: 18. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

Kuwait became an important trading port for import and export of goods from India, Africa and Arabia.

Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Al-Jassar, Mohammad Khalid A. (May 2009). Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya (PhD thesis). The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. p. 66.

- Bennis, Phyllis; Moushabeck, Michel, eds. (1991). Beyond the Storm: A Gulf Crisis Reader. Brooklyn, New York: Olive Branch Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-940793-82-8.

- Lauterpacht, Elihu; Greenwood, C. J.; Weller, Marc (1991). The Kuwait Crisis: Basic Documents. Cambridge international documents series, Issue 1. Cambridge, UK: Research Centre for International Law, Cambridge University Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-521-46308-9.

- Al-Jassar, Mohammad Khalid A. (May 2009). Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya (PhD thesis). The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. p. 67.

- Abdullah, Thabit A. J. (2001). Merchants, Mamluks, and Murder: The Political Economy of Trade in Eighteenth-Century Basra. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7914-4807-6.

- Sagher, Mostafa Ahmed. The impact of economic activities on the social and political structures of Kuwait (1896–1946) (PDF) (PhD). Durham, UK: Durham University. p. 108. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2016.

- Sweet, Louise Elizabeth (1970). Peoples and Cultures of the Middle East: Cultural depth and diversity. American Museum of Natural History, Natural History Press. p. 156.

The port of Kuwait was then, and is still, the principal dhow-building and trading port of the Persian Gulf, though offering little trade itself.

- Nijhoff, M. (1974). Bijdragen tot de taal-, land- en volkenkunde (in Dutch). Volume 130. Leiden, Netherlands: Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. p. 111.

- Aggarwal, Jatendra M., ed. (1965). Indian Foreign Affairs. Volume 8. p. 29.

- Sanger, Richard Harlakenden (1970). The Arabian Peninsula. Books for Libraries Press. p. 150.

- Al-Jassar, Mohammad Khalid A. Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya (PhD thesis). The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. p. 68.

- Hasan, Mohibbul, ed. (2007) [First published 1968]. Waqai-i manazil-i Rum: Tipu Sultan's mission to Constantinople. Delhi, India: Aakar Books. p. 18. ISBN 9788187879565.

For owing to Basra's misfortunes, Kuwait and Zubarah became rich.

- Fattah, Hala Mundhir (1997). The Politics of Regional Trade in Iraq, Arabia, and the Gulf, 1745–1900. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7914-3113-9.

- Agius, Dionisius A. (2012). Seafaring in the Arabian Gulf and Oman: People of the Dhow. New York: Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-136-20182-0.

- Ágoston, Gábor; Masters, Bruce (2009). Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire. New York: Infobase Publishing. p. 321. ISBN 978-1-4381-1025-7.

- Al-Jassar, Mohammad Khalid A. (May 2009). Constancy and Change in Contemporary Kuwait City: The Socio-cultural Dimensions of the Kuwait Courtyard and Diwaniyya (PhD thesis). The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. p. 80.

- Casey, Michael S. (2007). The History of Kuwait. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-313-34073-4.

- LSE and Michael Herb. March 2016. "The origins of Kuwait's National Assembly"

- Batatu, Hanna 1978. "The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq’s Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of its Communists, Ba’athists and Free Officers" Princeton p. 189

- Al Sager, Noura, ed. (2014). Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait's Modern Era Between Memory and Forgetting. National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters. p. 7. ISBN 9789990604238.

- Al-Nakib, Farah (2014). Al-Nakib, Farah (ed.). "Kuwait's Modernity Between Memory and Forgetting". Academia.edu: 7. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017.

- Farid, Alia (2014). "Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition". aliafarid.net. Archived from the original on 30 October 2016.

- Gonzales, Desi (November–December 2014). "Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait at the 14th International Architecture Exhibition". Art Papers. Archived from the original on 24 December 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2015.

- Tsourapas, Gerasimos (2 July 2016). "Nasser's Educators and Agitators across al-Watan al-'Arabi: Tracing the Foreign Policy Importance of Egyptian Regional Migration, 1952–1967" (PDF). British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (3): 324–341. doi:10.1080/13530194.2015.1102708. ISSN 1353-0194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2019.

- Bourisly, Nibal K.; Al-hajji, Maher N. (2004). "Kuwait's National Day: Four Decades of Transformed Celebrations". In Fuller, Linda K. (ed.). National Days/national Ways: Historical, Political, and Religious Celebrations Around the World. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9780275972707. Archived from the original on 14 February 2017. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- "Looking for Origins of Arab Modernism in Kuwait". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on 11 July 2015.

- Al-Nakib, Farah (1 March 2014). "Towards an Urban Alternative for Kuwait: Protests and Public Participation". Built Environment. 40 (1): 101–117. doi:10.2148/benv.40.1.101. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017.

- "Cultural developments in Kuwait". March 2013. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018.

- Chee Kong, Sam (1 March 2014). "What Can Nations Learn from Norway and Kuwait in Managing Sovereign Wealth Funds". Market Oracle. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014.

- al-Nakib, Farah (17 September 2014). "Understanding Modernity: A Review of the Kuwait Pavilion at the Venice Biennale". Jadaliyya. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- Sajjad, Valiya S. "Kuwait Literary Scene A Little Complex". Arab Times. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

A magazine, Al Arabi, was published in 1958 in Kuwait. It was the most popular magazine in the Arab world. It came out it in all the Arabic countries, and about a quarter million copies were published every month.

- Gunter, Barrie; Dickinson, Roger, eds. (2013). News Media in the Arab World: A Study of 10 Arab and Muslim Countries. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4411-0239-3.

- Sager, Abdulaziz; Koch, Christian; Tawfiq Ibrahim, Hasanain, eds. (2008). Gulf Yearbook 2006–2007. I. B. Tauris. p. 39.

The Kuwaiti press has always enjoyed a level of freedom unparalleled in any other Arab country.

- Muslim Education Quarterly. 8. Islamic Academy. 1990. p. 61.

Kuwait is a primary example of a Muslim society which embraced liberal and Western attitudes throughout the sixties and seventies.

- Rubin, Barry, ed. (2010). Guide to Islamist Movements. Volume 1. Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe. p. 306. ISBN 978-0-7656-4138-0.

- Wheeler, Deborah L. (2006). The Internet in the Middle East: Global Expectations And Local Imaginations. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7914-6586-8.

- "Kuwait unveils $775M Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre". 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- "Kuwait's Souk al-Manakh Stock Bubble". Stock-market-crash.net. 23 June 2012. Archived from the original on 19 May 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- Bansal, Narottam P.; Singh, Jitendra P.; Ko, Song; Castro, Ricardo; Pickrell, Gary; Manjooran, Navin Jose; Nair, Mani; Singh, Gurpreet, eds. (1 July 2013). Processing and Properties of Advanced Ceramics and Composites. 240. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 205. ISBN 978-1-118-74411-6.

- "Iraqi Invasion of Kuwait; 1990". Acig.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Gregory, Derek (2004). The Colonial Present: Afghanistan, Palestine, Iraq. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-57718-090-6. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Iraq and Kuwait: 1972, 1990, 1991, 1997". Earthshots: Satellite Images of Environmental Change. Archived from the original on 29 April 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2013.

- "Iraq and Kuwait Discuss Fate of 600 Missing Since Gulf War". Los Angeles Times. Associated Press. 9 January 2003. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014.

- "Kuwait ranks top among Arab states in human development – UNDP report". KUNA. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 August 2016.

- "Human Development Index 2009" (PDF). Human Development Report. hdr.undp.org. p. 143. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 May 2014.

- "Human Development Index 2007/2008" (PDF). Human Development Report. p. 233. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 April 2014.

- "Human Development Index 2006" (PDF). Human Development Report. p. 283. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 March 2016.

- "Kuwait highest in closing gender gap: WEF". Archived from the original on 12 August 2016. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- "The Global Gender Gap Index 2014 – World Economic Forum". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 14 April 2017.

- "Global Gender Gap Index Results in 2015". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 5 June 2016.

- "Sea City achieves the impossible". The Worldfolio. March 2016. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "Tamdeen Group's US$700 million Al Khiran development to bolster Kuwait's retail and tourism growth". Tamdeen Group. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016.

- "Kuwait National Cultural District Museums Director" (PDF). 28 August 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2018.

- "Kuwait National Cultural District". Archived from the original on 29 August 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

- "Opening of the Sheikh Jaber Al Ahmad Cultural Centre a milestone in the illustrious company's history". 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016.

- "أمير الكويت يدشن أكبر مركز ثقافي في الشرق الأوسط.. و4 جواهر تضيء شاطئ الخليج". Oman Daily (in Arabic). Archived from the original on 29 August 2017.

- "UK Trade & Investment" (PDF). UK Trade & Investment. June 2016. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 December 2016.

- "The Kuwait National Development Plan". New Kuwait Summit. 30 July 2018. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- Clive Holes (2004). Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties. Georgetown University Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-1-58901-022-2. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017.

- Ali Alawi (6 March 2013). "Ali's roadtrip from Bahrain to Kuwait (PHOTOS)". Archived from the original on 17 April 2016.

The trip to Kuwait – a country that has built a deep connection with people in the Persian Gulf thanks to its significant drama productions in theater, television, and even music – started with 25 kilometers of spectacular sea view

- Zubir, S.S.; Brebbia, C.A., eds. (2014). The Sustainable City VIII (2 Volume Set): Urban Regeneration and Sustainability. Volume 179 of WIT Transactions on Ecology and the Environment. Ashurst, Southampton, UK: WIT Press. p. 599. ISBN 978-1-84564-746-9.

- Alazemi, Einas. The role of fashion design in the construct of national identity of Kuwaiti women in the 21st century (PhD). University of Southampton. p. 140–199. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- Al Sager, Noura, ed. (2014). Acquiring Modernity: Kuwait's Modern Era Between Memory and Forgetting. National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters. p. 7. ISBN 9789990604238.

- "The Situation of Women in the Gulf States" (PDF). p. 18. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 June 2017.

- Karen E. Young (17 December 2015). "Small Victories for GCC Women: More Educated, More Unemployed". The Arab Gulf States Institute. Archived from the original on 17 June 2017.

- Karen E. Young. "More Educated, Less Employed: The Paradox of Women's Employment in the Gulf" (PDF). pp. 7–8. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 August 2017.

- "Kuwait leads Gulf states in women in workforce". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 14 May 2016.

- Stephenson, Lindsey. "Women and the Malleability of the Kuwaiti Diwaniyya". p. 190. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017.

- Al Mukrashi, Fahad (22 August 2015). "Omanis turn their backs on local dramas". Gulf News. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016.

Kuwait's drama industry tops other Gulf drama as it has very prominent actors and actresses, enough scripts and budgets, produces fifteen serials annually at least.

- Hammond, Andrew, ed. (2017). Pop Culture in North Africa and the Middle East: Entertainment and Society Around the World. California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 143–144. ISBN 9781440833847.

- "Closer cultural relations between the two countries". Oman Daily Observer. 20 February 2017. Archived from the original on 15 April 2017.

The Kuwaiti television is considered the most active in the Gulf Arab region, as it has contributed to the development of television drama in Kuwait and the Persian Gulf region. Therefore, all the classics of the Gulf television drama are today Kuwaiti dramas by Kuwaiti actors

- "Big plans for small screens". BroadcastPro Me. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016.

Around 90% of Khaleeji productions take place in Kuwait.

- Papavassilopoulos, Constantinos (10 April 2014). "OSN targets new markets by enriching its Arabic content offering". IHS Inc. Archived from the original on 22 April 2016.

- Fattahova, Nawara (26 March 2015). "First Kuwaiti horror movie to be set in 'haunted' palace". Kuwait Times. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015.

Kuwait's TV soaps and theatrical plays are among the best in the region and second most popular after Egypt in the Middle East.

- Bjørn T. Asheim. "An Innovation driven Economic Diversification Strategy for Kuwait" (PDF). Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. p. 9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "Kuwaiti Drama Museum: formulating thoughts of the Gulf". 23 May 2014. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016.

- Mansfield, Peter (1990). Kuwait: vanguard of the Gulf. Hutchinson. p. 113. Archived from the original on 16 April 2017.

- "Kuwait Cultural Days kick off in Seoul". Kuwait News Agency (in Arabic). 18 December 2015. Archived from the original on 13 July 2016.

- Hammond, Andrew (2007). Popular Culture in the Arab World: Arts, Politics, and the Media. Cairo, Egypt: American University in Cairo Press. p. 277. ISBN 9789774160547.

- Cavendish, Marshall (2006). World and Its Peoples, Volume 1. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7614-7571-2. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017.

- Watson, Katie (18 December 2010). "Reviving Kuwait's theatre industry". BBC News. Archived from the original on 11 November 2014.

- Herbert, Ian; Leclercq, Nicole, eds. (2000). "An Account of the Theatre Seasons 1996–97, 1997–98 and 1998–99". The World of Theatre (2000 ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-415-23866-3.

- Rubin, Don, ed. (1999). "Kuwait". The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre. Volume 4: The Arab world. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 143. ISBN 978-0-415-05932-9.

- Alhajri, Khalifah Rashed. A Scenographer's Perspective on Arabic Theatre and Arab-Muslim Identity (PDF) (PhD). Leeds, UK: University of Leeds. p. 207. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 March 2017.

- "Shooting the Past". y-oman.com. 11 July 2013. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016.

Most Omanis who get to study drama abroad tend to go to Kuwait or Egypt. In the Gulf, Kuwait has long been a pioneer in theatre, film and television since the establishment of its Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts (HIDA) in 1973. By contrast, there is no drama college or film school in Oman, although there is a drama course at Sultan Qaboos University.

- Herbert, Ian; Leclercq, Nicole, eds. (2003). "World of Theatre 2003 Edition: An Account of the World's Theatre Seasons". The World of Theatre (2003 ed.). London: Taylor & Francis. p. 214. ISBN 9781134402120.

- Fiona MacLeod. "The London musician who found harmony in Kuwait". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 9 April 2017.

- Bloom, Jonathan; Sheila, Blair, eds. (2009). Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture: Three-Volume Set (2009 ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 405. ISBN 978-0-19-530991-1. Archived from the original on 30 April 2016.

- Zuhur, Sherifa, ed. (2001). Colors of Enchantment: Theater, Dance, Music, and the Visual Arts of the Middle East (2001 ed.). New York: American University in Cairo Press. p. 383. ISBN 9781617974809.

- Bjørn T. Asheim. "An Innovation driven Economic Diversification Strategy for Kuwait" (PDF). Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences. pp. 49–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- Al Qassemi, Sultan Sooud (22 November 2013). "Correcting misconceptions of the Gulf's modern art movement". Al-Monitor: The Pulse of the Middle East. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- "Kuwait". Atelier Voyage. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- Kristine Khouri. "Mapping Arab Art through the Sultan Gallery". ArteEast. Archived from the original on 11 October 2016.

- "The Sultan Gallery – Kristine Khouri". Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- "Culture of Kuwait". Kuwait Embassy in Austria. Archived from the original on 2 April 2017.

- "Art Galleries and Art Museums in Kuwait". Art Kuwait. Archived from the original on 3 May 2017.

- "Egyptian Artist Fatma, talks about the gateway to human faces and equality for all". Reconnecting Arts. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- "Kuwaiti Artist Rua AlShaheen tells us about recycling existing elements to tell a new narrative". Reconnecting Arts. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017.

- "Farah Behbehani & the Story of the letter Haa '". Al Ostoura Magazine. Archived from the original on 22 August 2017.

- Muayad H., Hussain (2012). Modern Art from Kuwait: Khalifa Qattan and Circulism (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Birmingham. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2016.

- "Khalifa Qattan, Founder of Circulism". Archived from the original on 29 November 2014.

- "Interview with Ali Al-Youha – Secretary General of Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters (NCCAL)" (PDF). oxgaps.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2017.

- "Kuwait celebrates formative arts festival". Kuwait News Agency (KUNA). Archived from the original on 31 March 2017.

- "KAA honors winners of His Highness Amir formative arts award". Kuwait News Agency (KUNA). Archived from the original on 31 March 2017.

- "12th Kuwait International Biennial". AsiaArt archive. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017.