Library

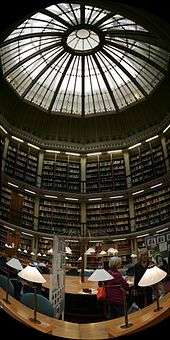

A library is a curated collection of sources of information and similar resources, selected by experts and made accessible to a defined community for reference or borrowing, often in a quiet environment conducive to study. It provides physical or digital access to material, and may be a physical location or a virtual space, or both. A library's collection can include books, periodicals, newspapers, manuscripts, films, maps, prints, documents, microform, CDs, cassettes, videotapes, DVDs, Blu-ray Discs, e-books, audiobooks, databases, table games, video games and other formats. Libraries range widely in size up to millions of items. The word for "library" in many modern languages is derived from Ancient Greek βιβλιοθήκη (bibliothēkē), originally meaning bookcase, via Latin bibliotheca.

.jpg)

The first libraries consisted of archives of the earliest form of writing—the clay tablets in cuneiform script discovered in Sumer, some dating back to 2600 BC. Private or personal libraries made up of written books appeared in classical Greece in the 5th century BC. In the 6th century, at the very close of the Classical period, the great libraries of the Mediterranean world remained those of Constantinople and Alexandria. The libraries of Timbuktu were also established around this time and attracted scholars from all over the world.

A library is organized for use and maintained by a public body, an institution, a corporation, or a private individual. Public and institutional collections and services may be intended for use by people who choose not to—or cannot afford to—purchase an extensive collection themselves, who need material no individual can reasonably be expected to have, or who require professional assistance with their research. In addition to providing materials, libraries also provide the services of librarians who are experts at finding and organizing information and at interpreting information needs. Libraries often provide quiet areas for studying, and they also often offer common areas to facilitate group study and collaboration. Libraries often provide public facilities for access to their electronic resources and the Internet.

Modern libraries are increasingly being redefined as places to get unrestricted access to information in many formats and from many sources. They are extending services beyond the physical walls of a building, by providing material accessible by electronic means, and by providing the assistance of librarians in navigating and analyzing very large amounts of information with a variety of digital resources. Libraries are increasingly becoming community hubs where programs are delivered and people engage in lifelong learning.

History

The history of libraries began with the first efforts to organize collections of documents. Topics of interest include accessibility of the collection, acquisition of materials, arrangement and finding tools, the book trade, the influence of the physical properties of the different writing materials, language distribution, role in education, rates of literacy, budgets, staffing, libraries for specially targeted audiences, architectural merit, patterns of usage, and the role of libraries in a nation's cultural heritage, and the role of government, church or private sponsorship. Since the 1960s, issues of computerization and digitization have arisen.

Types

Many institutions make a distinction between a circulating or lending library, where materials are expected and intended to be loaned to patrons, institutions, or other libraries, and a reference library where material is not lent out. Travelling libraries, such as the early horseback libraries of eastern Kentucky[1] and bookmobiles, are generally of the lending type. Modern libraries are often a mixture of both, containing a general collection for circulation, and a reference collection which is restricted to the library premises. Also, increasingly, digital collections enable broader access to material that may not circulate in print, and enables libraries to expand their collections even without building a larger facility. Lamba (2019) reinforced this idea by observing that “today’s libraries have become increasingly multi-disciplinary, collaborative and networked” and that applying Web 2.0 tools to libraries would “not only connect the users with their community and enhance communication but will also help the librarians to promote their library’s activities, services, and products to target both their actual and potential users”.[2]

Academic libraries

Academic libraries are generally located on college and university campuses and primarily serve the students and faculty of that and other academic institutions. Some academic libraries, especially those at public institutions, are accessible to members of the general public in whole or in part.

Academic libraries are libraries that are hosted in post-secondary educational institutions, such as colleges and universities. Their main function are to provide support in research and resource linkage for students and faculty of the educational institution. Specific course-related resources are usually provided by the library, such as copies of textbooks and article readings held on 'reserve' (meaning that they are loaned out only on a short-term basis, usually a matter of hours). Some academic libraries provide resources not usually associated with libraries, such as the ability to check out laptop computers, web cameras, or scientific calculators.

Academic libraries offer workshops and courses outside of formal, graded coursework, which are meant to provide students with the tools necessary to succeed in their programs.[3] These workshops may include help with citations, effective search techniques, journal databases, and electronic citation software. These workshops provide students with skills that can help them achieve success in their academic careers (and often, in their future occupations), which they may not learn inside the classroom.

The academic library provides a quiet study space for students on campus; it may also provide group study space, such as meeting rooms. In North America, Europe, and other parts of the world, academic libraries are becoming increasingly digitally oriented. The library provides a "gateway" for students and researchers to access various resources, both print/physical and digital.[4] Academic institutions are subscribing to electronic journals databases, providing research and scholarly writing software, and usually provide computer workstations or computer labs for students to access journals, library search databases and portals, institutional electronic resources, Internet access, and course- or task-related software (i.e. word processing and spreadsheet software). Some academic libraries take on new roles, for instance, acting as an electronic repository for institutional scholarly research and academic knowledge, such as the collection and curation of digital copies of students' theses and dissertations.[5][6] Moreover, academic libraries are increasingly acting as publishers on their own on a not-for-profit basis, especially in the form of fully Open Access institutional publishers.[7]

Children's libraries

Children's libraries are special collections of books intended for juvenile readers and usually kept in separate rooms of general public libraries. Some children's libraries have entire floors or wings dedicated to them in bigger libraries while smaller ones may have a separate room or area for children. They are an educational agency seeking to acquaint the young with the world's literature and to cultivate a love for reading. Their work supplements that of the public schools.[8][9]

Services commonly provided by public libraries may include storytelling sessions for infants, toddlers, preschool children, or after-school programs, all with an intention of developing early literacy skills and a love of books. One of the most popular programs offered in public libraries are summer reading programs for children, families, and adults.[10]

Another popular reading program for children is PAWS TO READ or similar programs where children can read to certified therapy dogs. Since animals are a calming influence and there is no judgment, children learn confidence and a love of reading. Many states have these types of programs: parents need simply ask their librarian to see if it is available at their local library.[11]

National libraries

A national or state library serves as a national repository of information, and has the right of legal deposit, which is a legal requirement that publishers in the country need to deposit a copy of each publication with the library. Unlike a public library, a national library rarely allows citizens to borrow books. Often, their collections include numerous rare, valuable, or significant works. There are wider definitions of a national library, putting less emphasis on the repository character.[12][13] The first national libraries had their origins in the royal collections of the sovereign or some other supreme body of the state.

Many national libraries cooperate within the National Libraries Section of the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) to discuss their common tasks, define and promote common standards, and carry out projects helping them to fulfill their duties. The national libraries of Europe participate in The European Library which is a service of the Conference of European National Librarians (CENL).

Public lending libraries

A public library provides services to the general public. If the library is part of a countywide library system, citizens with an active library card from around that county can use the library branches associated with the library system. A library can serve only their city, however, if they are not a member of the county public library system. Much of the materials located within a public library are available for borrowing. The library staff decides upon the number of items patrons are allowed to borrow, as well as the details of borrowing time allotted. Typically, libraries issue library cards to community members wishing to borrow books. Often visitors to a city are able to obtain a public library card.

Many public libraries also serve as community organizations that provide free services and events to the public, such as reading groups and toddler story time. For many communities, the library is a source of connection to a vast world, obtainable knowledge and understanding, and entertainment. According to a study by the Pennsylvania Library Association, public library services play a major role in fighting rising illiteracy rates among youths.[14] Public libraries are protected and funded by the public they serve.

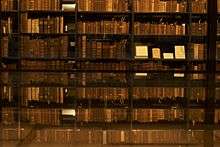

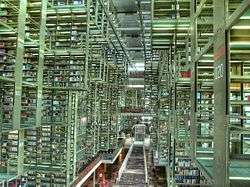

As the number of books in libraries have steadily increased since their inception, the need for compact storage and access with adequate lighting has grown. The stack system involves keeping a library's collection of books in a space separate from the reading room. This arrangement arose in the 19th century. Book stacks quickly evolved into a fairly standard form in which the cast iron and steel frameworks supporting the bookshelves also supported the floors, which often were built of translucent blocks to permit the passage of light (but were not transparent, for reasons of modesty). The introduction of electrical lighting had a huge impact on how the library operated. The use of glass floors was largely discontinued, though floors were still often composed of metal grating to allow air to circulate in multi-story stacks. As more space was needed, a method of moving shelves on tracks (compact shelving) was introduced to cut down on otherwise wasted aisle space.

Library 2.0, a term coined in 2005, is the library's response to the challenge of Google and an attempt to meet the changing needs of users by using web 2.0 technology. Some of the aspects of Library 2.0 include, commenting, tagging, bookmarking, discussions, use of online social networks by libraries, plug-ins, and widgets.[15] Inspired by web 2.0, it is an attempt to make the library a more user-driven institution.

Despite the importance of public libraries, they are routinely having their budgets cut by state legislature. Funding has dwindled so badly that many public libraries have been forced to cut their hours and release employees.[16]

Reference libraries

A reference library does not lend books and other items; instead, they can only be read at the library itself. Typically, such libraries are used for research purposes, for example at a university. Some items at reference libraries may be historical and even unique. Many lending libraries contain a "reference section", which holds books, such as dictionaries, which are common reference books, and are therefore not lent out.[17] Such reference sections may be referred to as "reading rooms", which may also include newspapers and periodicals.[18] An example of a reading room is the Hazel H. Ransom Reading Room at the Harry Ransom Center of the University of Texas at Austin, which maintains the papers of literary agent Audrey Wood.[19]

Research libraries

A research library is a collection of materials on one or more subjects.[20] A research library supports scholarly or scientific research and will generally include primary as well as secondary sources; it will maintain permanent collections and attempt to provide access to all necessary materials. A research library is most often an academic or national library, but a large special library may have a research library within its special field, and a very few of the largest public libraries also serve as research libraries. A large university library may be considered a research library; and in North America, such libraries may belong to the Association of Research Libraries.[21] In the United Kingdom, they may be members of Research Libraries UK (RLUK).[22]

A research library can be either a reference library, which does not lend its holdings, or a lending library, which does lend all or some of its holdings. Some extremely large or traditional research libraries are entirely reference in this sense, lending none of their materials; most academic research libraries, at least in the US and the UK, now lend books, but not periodicals or other materials. Many research libraries are attached to a parental organization and serve only members of that organization. Examples of research libraries include the British Library, the Bodleian Library at Oxford University and the New York Public Library Main Branch on 42nd Street in Manhattan, State Public Scientific Technological Library of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Science.[23][24]

Digital libraries

Digital libraries are libraries that house digital resources. They are defined as an organization and not a service that provide access to digital works, have a preservation responsibility to provide future access to materials, and provides these items easily and affordably.[25] The definition of a digital library implies that "a digital library uses a variety of software, networking technologies and standards to facilitate access to digital content and data to a designated user community."[26] Access to digital libraries can be influenced by several factors, either individually or together. The most common factors that influence access are: The library's content, the characteristics and information needs of the target users, the library's digital interface, the goals and objectives of the library's organizational structure, and the standards and regulations that govern library use.[27] Access will depend on the users ability to discover and retrieve documents that interest them and that they require, which in turn is a preservation question. Digital objects cannot be preserved passively, they must be curated by digital librarians to ensure the trust and integrity of the digital objects.[28]

One of the biggest considerations for digital librarians is the need to provide long-term access to their resources; to do this, there are two issues requiring watchfulness: Media failure and format obsolescence. With media failure, a particular digital item is unusable because of some sort of error or problem. A scratched CD-Rom, for example, will not display its contents correctly, but another, unscratched disk will not have that problem. Format obsolescence is when a digital format has been superseded by newer technology, and so items in the old format are unreadable and unusable. Dealing with media failure is a reactive process, because something is done only when a problem presents itself. In contrast, format obsolescence is preparatory, because changes are anticipated and solutions are sought before there is a problem.[29]

Future trends in digital preservation include: Transparent enterprise models for digital preservation, launch of self-preserving objects, increased flexibility in digital preservation architectures, clearly defined metrics for comparing preservation tools, and terminology and standards interoperability in real time.[29]

Special libraries

All other libraries fall into the "special library" category. Many private businesses and public organizations, including hospitals, churches, museums, research laboratories, law firms, and many government departments and agencies, maintain their own libraries for the use of their employees in doing specialized research related to their work. Depending on the particular institution, special libraries may or may not be accessible to the general public or elements thereof. In more specialized institutions such as law firms and research laboratories, librarians employed in special libraries are commonly specialists in the institution's field rather than generally trained librarians, and often are not required to have advanced degrees in a specifically library-related field due to the specialized content and clientele of the library.

Special libraries can also include women's libraries or LGBTQ libraries, which serve the needs of women and the LGBTQ community. Libraries and the LGBTQ community have an extensive history, and there are currently many libraries, archives, and special collections devoted to preserving and helping the LGBTQ community. Women's libraries, such as the Vancouver Women's Library or the Women's Library @LSE are examples of women's libraries that offer services to women and girls and focus on women's history.

Some special libraries, such as governmental law libraries, hospital libraries, and military base libraries commonly are open to public visitors to the institution in question. Depending on the particular library and the clientele it serves, special libraries may offer services similar to research, reference, public, academic, or children's libraries, often with restrictions such as only lending books to patients at a hospital or restricting the public from parts of a military collection. Given the highly individual nature of special libraries, visitors to a special library are often advised to check what services and restrictions apply at that particular library.

Special libraries are distinguished from special collections, which are branches or parts of a library intended for rare books, manuscripts, and other special materials, though some special libraries have special collections of their own, typically related to the library's specialized subject area.

For more information on specific types of special libraries, see law libraries, medical libraries, music libraries, or transportation libraries.

Organization

Most libraries have materials arranged in a specified order according to a library classification system, so that items may be located quickly and collections may be browsed efficiently.[30] Some libraries have additional galleries beyond the public ones, where reference materials are stored. These reference stacks may be open to selected members of the public. Others require patrons to submit a "stack request", which is a request for an assistant to retrieve the material from the closed stacks: see List of closed stack libraries (in progress).

Larger libraries are often divided into departments staffed by both paraprofessionals and professional librarians.

- Circulation (or Access Services) – Handles user accounts and the loaning/returning and shelving of materials.[31]

- Collection Development – Orders materials and maintains materials budgets.

- Reference – Staffs a reference desk answering questions from users (using structured reference interviews), instructing users, and developing library programming. Reference may be further broken down by user groups or materials; common collections are children's literature, young adult literature, and genealogy materials.

- Technical Services – Works behind the scenes cataloging and processing new materials and deaccessioning weeded materials.

- Stacks Maintenance – Re-shelves materials that have been returned to the library after patron use and shelves materials that have been processed by Technical Services. Stacks Maintenance also shelf reads the material in the stacks to ensure that it is in the correct library classification order.

Basic tasks in library management include the planning of acquisitions (which materials the library should acquire, by purchase or otherwise), library classification of acquired materials, preservation of materials (especially rare and fragile archival materials such as manuscripts), the deaccessioning of materials, patron borrowing of materials, and developing and administering library computer systems.[32] More long-term issues include the planning of the construction of new libraries or extensions to existing ones, and the development and implementation of outreach services and reading-enhancement services (such as adult literacy and children's programming). Library materials like books, magazines, periodicals, CDs, etc. are managed by Dewey Decimal Classification Theory and modified Dewey Decimal Classification Theory is more practical reliable system for library materials management.[33]

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) has published several standards regarding the management of libraries through its Technical Committee 46 (TC 46),[34] which is focused on "libraries, documentation and information centers, publishing, archives, records management, museum documentation, indexing and abstracting services, and information science". The following is a partial list of some of them:[35]

- ISO 2789:2006 Information and documentation—International library statistics

- ISO 11620:1998 Information and documentation—Library performance indicators

- ISO 11799:2003 Information and documentation—Document storage requirements for archive and library materials

- ISO 14416:2003 Information and documentation—Requirements for binding of books, periodicals, serials, and other paper documents for archive and library use—Methods and materials

- ISO/TR 20983:2003 Information and documentation—Performance indicators for electronic library services

Codes of conduct

Libraries may have rules which limit noise levels, the use of mobile phones, and/or the consumption of food and drink.[36]

In UK local authority libraries, this has been challenged recently as toddler 'bounce and rhyme' sessions have been held.[37] Noise levels in public libraries have become a matter of controversy.[38][39]

Buildings

Librarians have sometimes complained[40] that some of the library buildings which have been used to accommodate libraries have been inadequate for the demands made upon them. In general, this condition may have resulted from one or more of the following causes:

- an effort to erect a monumental building; most of those who commission library buildings are not librarians and their priorities may be different

- to conform it to a type of architecture unsuited to library purposes

- the appointment, often by competition, of an architect unschooled in the requirements of a library

- failure to consult with the librarian or with library experts

Much advancement has undoubtedly been made toward cooperation between architect and librarian, and many good designers have made library buildings their specialty; nevertheless it seems that the ideal type of library is not yet realized—the type so adapted to its purpose that it would be immediately recognized as such, as is the case with school buildings. This does not mean that library constructions should conform rigidly to a fixed standard of appearance and arrangement, but it does mean that the exterior should express as nearly as possible the purpose and functions of the interior.[41]

Usage

Some patrons may not know how to fully use the library's resources.[42] This can be due to individuals' unease in approaching a staff member. Ways in which a library's content is displayed or accessed may have the most impact on use. An antiquated or clumsy search system, or staff unwilling or untrained to engage their patrons, will limit a library's usefulness. In the public libraries of the United States, beginning in the 19th century, these problems drove the emergence of the library instruction movement, which advocated library user education.[43] One of the early leaders was John Cotton Dana.[44] The basic form of library instruction is sometimes known as information literacy.[45]

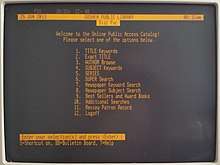

Libraries should inform their users of what materials are available in their collections and how to access that information. Before the computer age, this was accomplished by the card catalogue—a cabinet (or multiple cabinets) containing many drawers filled with index cards that identified books and other materials. In a large library, the card catalogue often filled a large room.

The emergence of the Internet, however, has led to the adoption of electronic catalogue databases (often referred to as "webcats" or as online public access catalogues, OPACs), which allow users to search the library's holdings from any location with Internet access.[46] This style of catalogue maintenance is compatible with new types of libraries, such as digital libraries and distributed libraries, as well as older libraries that have been retrofitted. Large libraries may be scattered within multiple buildings across a town, each having multiple floors, with multiple rooms housing their resources across a series of shelves called bays. Once a user has located a resource within the catalogue, they must then use navigational guidance to retrieve the resource physically, a process that may be assisted through signage, maps, GPS systems, or RFID tagging.

Finland has the highest number of registered book borrowers per capita in the world. Over half of Finland's population are registered borrowers.[47] In the US, public library users have borrowed on average roughly 15 books per user per year from 1856 to 1978. From 1978 to 2004, book circulation per user declined approximately 50%. The growth of audiovisuals circulation, estimated at 25% of total circulation in 2004, accounts for about half of this decline.[48]

Shift to digital libraries

In the 21st century, there has been increasing use of the Internet to gather and retrieve data. The shift to digital libraries has greatly impacted the way people use physical libraries. Between 2002 and 2004, the average American academic library saw the overall number of transactions decline approximately 2.2%.[49] Libraries are trying to keep up with the digital world and the new generation of students that are used to having information just one click away. For example, the University of California Library System saw a 54% decline in circulation between 1991 and 2001 of 8,377,000 books to 3,832,000.[50]

These facts might be a consequence of the increased availability of e-resources. In 1999–2000, 105 ARL university libraries spent almost $100 million on electronic resources, which is an increase of nearly $23 million from the previous year.[51] A 2003 report by the Open E-book Forum found that close to a million e-books had been sold in 2002, generating nearly $8 million in revenue.[52] Another example of the shift to digital libraries can be seen in Cushing Academy's decision to dispense with its library of printed books—more than 20,000 volumes in all—and switch over entirely to digital media resources.[53]

One claim to why there is a decrease in the usage of libraries stems from the observation of the research habits of undergraduate students enrolled in colleges and universities. There have been claims that college undergraduates have become more used to retrieving information from the Internet than a traditional library. As each generation becomes more in tune with the Internet, their desire to retrieve information as quickly and easily as possible has increased. Finding information by simply searching the Internet could be much easier and faster than reading an entire book. In a survey conducted by NetLibrary, 93% of undergraduate students claimed that finding information online makes more sense to them than going to the library. Also, 75% of students surveyed claimed that they did not have enough time to go to the library and that they liked the convenience of the Internet. While the retrieving information from the Internet may be efficient and time saving than visiting a traditional library, research has shown that undergraduates are most likely searching only .03% of the entire web.[54] The information that they are finding might be easy to retrieve and more readily available, but may not be as in depth as information from other resources such as the books available at a physical library.

In the mid-2000s, Swedish company Distec invented a library book vending machine known as the GoLibrary, that offers library books to people where there is no branch, limited hours, or high traffic locations such as El Cerrito del Norte BART station in California.

The Internet

A library may make use of the Internet in a number of ways, from creating their own library website to making the contents of its catalogues searchable online. Some specialised search engines such as Google Scholar offer a way to facilitate searching for academic resources such as journal articles and research papers. The Online Computer Library Center allows anyone to search the world's largest repository of library records through its WorldCat online database.[55] Websites such as LibraryThing and Amazon provide abstracts, reviews, and recommendations of books.[55] Libraries provide computers and Internet access to allow people to search for information online.[56] Online information access is particularly attractive to younger library users.[57][58][59][60]

Digitization of books, particularly those that are out-of-print, in projects such as Google Books provides resources for library and other online users. Due to their holdings of valuable material, some libraries are important partners for search engines such as Google in realizing the potential of such projects and have received reciprocal benefits in cases where they have negotiated effectively.[61] As the prominence of and reliance on the Internet has grown, library services have moved the emphasis from mainly providing print resources to providing more computers and more Internet access.[62] Libraries face a number of challenges in adapting to new ways of information seeking that may stress convenience over quality,[63] reducing the priority of information literacy skills.[64] The potential decline in library usage, particularly reference services,[65] puts the necessity for these services in doubt.

Library scholars have acknowledged that libraries need to address the ways that they market their services if they are to compete with the Internet and mitigate the risk of losing users.[66] This includes promoting the information literacy skills training considered vital across the library profession.[64][67][68] However, marketing of services has to be adequately supported financially in order to be successful. This can be problematic for library services that are publicly funded and find it difficult to justify diverting tight funds to apparently peripheral areas such as branding and marketing.[69]

The privacy aspect of library usage in the Internet age is a matter of growing concern and advocacy; privacy workshops are run by the Library Freedom Project which teach librarians about digital tools (such as the Tor Project) to thwart mass surveillance.[70][71][72]

Associations

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) is the leading international association of library organisations. It is the global voice of the library and information profession, and its annual conference provides a venue for librarians to learn from one another.[73]

Library associations in Asia include the Indian Library Association (ILA),[74] Indian Association of Special Libraries and Information Centers (IASLIC),[75] Bengal Library Association (BLA), Kolkata,[76] Pakistan Library Association,[77] the Pakistan Librarians Welfare Organization,[78] the Bangladesh Association of Librarians, Information Scientists and Documentalists, the Library Association of Bangladesh, and the Sri Lanka Library Association (founded 1960).

National associations of the English-speaking world include the American Library Association, the Australian Library and Information Association, the Canadian Library Association, the Library and Information Association of New Zealand Aotearoa, and the Research Libraries UK (a consortium of 30 university and other research libraries in the United Kingdom). Library bodies such as CILIP (formerly the Library Association, founded 1877) may advocate the role that libraries and librarians can play in a modern Internet environment, and in the teaching of information literacy skills.[67][79]

Public library advocacy is support given to a public library for its financial and philosophical goals or needs. Most often this takes the form of monetary or material donations or campaigning to the institutions which oversee the library, sometimes by advocacy groups such as Friends of Libraries and community members. Originally, library advocacy was centered on the library itself, but current trends show libraries positioning themselves to demonstrate they provide "economic value to the community" in means that are not directly related to the checking out of books and other media.[80]

International protection

Libraries are considered part of the cultural heritage and are one of the primary objectives in many state and domestic conflicts and are at risk of destruction and looting. Financing is often carried out by robbing valuable library items. National and international coordination regarding military and civil structures for the protection of libraries is operated by Blue Shield International and UNESCO. From an international perspective, despite the partial dissolution of state structures and very unclear security situations as a result of the wars and unrest, robust undertakings to protect libraries are being carried out. The topic is also the creation of "no-strike lists", in which the coordinates of important cultural monuments such as libraries have been preserved.[81][82][83][84]

See also

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Controlled vocabulary

- Dewey Decimal Classification

- Digital reference

- Document management system

- Federal Depository Library Program

- Green library

- Information technology

- Integrated library system

- Interlibrary loan

- International Standard Book Number

- Libraries and the LGBTQ community

- Libraries in fiction

- Library anxiety

- Library assessment

- Library of Congress Classification

- Library of Congress Subject Headings

- Library portal

- Library Services and Construction Act

- Little Free Library

- National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped

- Private library

- Public library

- Public libraries in North America

- Roving reference

- Trends in library usage

Lists of libraries

References

- "The Amazing Story of Kentucky's Horseback Librarians (10 Photos)". Archive Project. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- Lamba, Manika. "Marketing of academic health libraries 2.0: a case study". Library Management. 40 (3/4): 155–177. doi:10.1108/LM-03-2018-0013.

- "St. George Library Workshops". utoronto.ca.

- Dowler, Lawrence (1997). Gateways to knowledge: the role of academic libraries in teaching, learning, and research. ISBN 0-262-04159-6

- "The Role of Academic Libraries in Universal Access to Print and Electronic Resources in the Developing Countries, Chinwe V. Anunobi, Ifeyinwa B. Okoye". Unllib.unl.edu. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "TSpace". utoronto.ca.

- "Library Publishing, or How to Make Use of Your Opportunities". LePublikateur. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Modell, David A. (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- L.O., Aina (2004). Library and Information Science Text for Africa. Ibadan, Nigeria: Third World Information Services Ltd. p. 31. ISBN 9783283618.

- Udomisor, I., Udomisor, E., & Smith, E. (2013). Management of Communication Crisis in a Library and Its Influence on Productivity. In Information and Knowledge Management (Vol. 3, No. 8, pp. 13–21)

- "Paws to read". Retrieved 1 April 2013.

- Line, Maurice B.; Line, J. (1979). "Concluding notes". National libraries, Aslib, pp. 317–18

- Lor, P.J.; Sonnekus, E.A.S. (1997). "Guidelines for Legislation for National Library Services" Archived 13 August 2006 at the Wayback Machine, IFLA. Retrieved on 10 January 2009.

- Celano, D., & Neumann, S.B. (2001). The role of public libraries in children's literacy development: An evaluation report. Pennsylvania, PA: Pennsylvania Library Association.

- Cohen, L.B. (2007). "A Manifesto for our time". American Libraries. 38: 47–49.

- Jaeger, Paul T.; Bertot, John Carol; Gorham, Ursula (January 2013). "Wake Up the Nation: Public Libraries, Policy Making, and Political Discourse". The Library Quarterly: Information, Community, Policy. 83 (1): 61–72. doi:10.1086/668582. JSTOR 10.1086/668582.

- Ehrenhaft, George; Howard Armstrong, William; Lampe, M. Willard (August 2004). Barron's pocket guide to study tips. Barron's Educational Series. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-7641-2693-2. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- Champneys, Amian L. (2007). Public Libraries. Jeremy Mills Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 978-1-905217-84-7. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- "Audrey Wood: An Inventory of Her Collection at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center." www.hrc.utexas.edu. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- Young, Heartsill (1983). ALA Glossary of Library and Information Science. Chicago: American Library Association. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-8389-0371-1. OCLC 8907224.

- "Association of Research Libraries (ARL) :: Member Libraries". arl.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- "RLUK: Research Libraries UK". RLUK. Retrieved 9 January 2013.

- "SPSTL SB RAS". www.spsl.nsc.ru. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "Our Story".

- Chowdhury, G.G.; Foo, C. (2012). Digital Libraries and Information Access: research perspectives. Chicago: Neal-Schuman. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-1-55570-914-3. OCLC 869282690.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chowdhury & Foo (2012), pp. 3–4.

- Chowdhury & Foo (2012), p. 49.

- Borgman, Christine L. (2007). Scholarship in the digital age: information, infrastructure, and the Internet. Cambridge: MIT Press. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-262-02619-2. OCLC 181028448.

- Chowdhury & Foo (2012), p. 211.

- "Library classification". britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Morris, V. & Bullard, J. (2009). Circulation Services. In Encyclopedia of Library and Information Sciences (3rd ed.).

- Stueart, Robert; Moran, Barbara B.; Morner, Claudia J. (2013). Library and information center management (Eighth ed.). Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited. ISBN 978-1-59884-988-2. OCLC 780481202.

- Bhattacharjee, Pijush Kanti (2010). "Modified Dewey Decimal Classification Theory for Library Materials Management". International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology. 1 (3): 292–94.

- "ISO – Technical committees – TC 46 – Information and documentation". ISO.org. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- "ISO – ISO Standards – TC 46 – Information and documentation". ISO.org. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- Leo Cutting, 'Students:how do you behave in the library?', Daily Express, April 2012

- Islington.gov.uk, libraries, family services

- Robert Mcneil, 'Time for quiet libraries to make a comeback', thecourier.co.uk, April 2019

- Eugene Henderson, 'Break the silence', Daily Express, 14/6/2015

- Bennett, Scott (April 2009). "Libraries and Learning: A History of Paradigm Change". Portal: Libraries and the Academy. 9 – via ProQuest.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wiley, Edwin (1920). . In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- "Library Usage - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics". www.sciencedirect.com. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Weiss, S.C. (2003). "The origin of library instruction in the United States, 1820–1900". Research Strategies. 19 (3/4): 233–43. doi:10.1016/j.resstr.2004.11.001.

- Mattson, K. (2000). "The librarian as secular minister to democracy: The life and ideas of John Cotton Dana". Libraries & Culture. 35 (4): 514–34.

- Robinson, T.E. (2006). "Information literacy: Adapting to the media age". Alki. 22 (1): 10–12.

- Sloan, B; White, M.S.B. (1992). "Online public access catalogs". Academic and Library Computing. 9 (2): 9–13. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000003734.

- Pantzar, Katja (September 2010). "The humble Number One: Finland". This is Finland. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- Statistics on Book Circulation Per User of U.S. Public Libraries Since 1856 from galbithink.org

- Applegate, Rachel. "Whose Decline? Which Academic Libraries are "Deserted" in Terms of Reference Transactions?" Reference & User Services Quarterly; 2nd ser. 48 (2008): 176–89. Print.

- University of California Library Statistics 1990–91, University-wide Library Planning, University of California Office of the President (July 1991): 12; University of California Library Statistics July 2001, 7, Ucop.edu Archived 2 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 July 2005; University of California Library Statistics July 2004, 7, Ucop.edu Archived 2 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 July 2005.

- "ARL Libraries Spend Nearly $100 Million on Electronic Resources," ARL Bimonthly Report 219, Association of Research Libraries (December 2001) Archived 21 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Striphas, Ted. The Late Age of Print: Everyday Book Culture From Consumerism to Control. New York City: Columbia University Press, 2009. Print.

- Striphas, Ted. "Books: "An Outdated Technology?" Weblog post. The Late Age of Print. 4 September 2009. Web. 19 November 2009. Thelateageofprint.org

- Troll, Denise A. "How and Why are Libraries Changing?" Digital Library Federation. Library Information Technology – Carnegie Mellon, 9 January 2001. Web. 29 November 2009. Diglib.org

- Grossman, W. M. (2009). "Why you can't find a library book in your search engine". The Guardian. Accessed: 23 March 2010

- Mostafa, J (2005). "Seeking Better Web Searches". Scientific American. 292 (2): 51–57. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0205-66.

- Corradini, E. (2006). "Teenagers Analyse their Public Library". New Library World; Vol. 107 (1230/1231), pp. 481–98. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. Retrieved 25 February 2010

- Department for Children, Schools and Families. (2005). Youth Matters. Archived 8 April 2010 at the UK Government Web Archive Accessed: 7 March 2010

- Nippold, M.A.; Duthie, J.K. & Larsen, J. (2005). "Literacy as a Leisure Activity: Free-time preferences of Older Children and Young Adolescents". Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 36 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2005/009). In: Snowball, C. (2008). "Enticing Teenagers into the Library". Library Review. Emerald Group Publishing. 57 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1108/00242530810845035. hdl:20.500.11937/6057.

- Museums, Libraries and Archives, Department of Culture, Media and Sport & Laser Foundation (June 2006). A Research Study of 14–35 year olds for the Future Development of Public Libraries (PDF) (Report). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2010.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Darnton, R. (2009). "Google & the Future of Books". New York Review of Books; 55 (2). Accessed: 23 March 2010

- Garrod, P. (2004). "Public Libraries: the changing face of the public library". Ariadne; Issue 39. Accessed 26 March 2010

- Abram, S. & Luther, J. (1 May 2004). "Born with the Chip: the next generation will profoundly impact both library service and the culture within the profession". Library Journal. Accessed: 26 March 2010

- Bell, S. (15 May 2005). "Backtalk: don't surrender library values". Library Journal. Archived from the original on 12 June 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2010.

- Novotny, E. (2002). "Reference service statistics and assessment. SPEC kit". Pennsylvania State University. Accessed: 16 March 2010

- Vrana, R., and Barbaric, A. (2007). "Improving visibility of public libraries in the local community: a study of five public libraries in Zagreb, Croatia". New Library World; 108 (9/10), pp. 435–44.

- CILIP (2010). "An introduction to information literacy". CILIP. London. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Kenney, B. (15 December 2004). "Googlizers vs. Resistors: library leaders debate our relationship with search engines". Library Journal. Archived from the original on 8 June 2005. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- Hood, D. & Henderson, K. (2005). "Branding in the United Kingdom Public Library Service". New Library World; 106 (1208/1209), pp. 16–28

- "SCREW YOU, FEDS! Dozen or more US libraries line up to run Tor exit nodes". Theregister.co.uk. Retrieved 21 September 2015.

- https://libraryfreedomproject.org/libraries-tor-freedom-and-resistance/ Library Freedom Project at Kilton Library

- https://journals.ala.org/rusq/article/view/5704/7092 The Tor Browser and Intellectual Freedom in the Digital Age

- "International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)". ifla.org. 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- "Welcome to Indian Library Association". Ilaindia.net. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Welcome to Indian Association of Special Libraries and Information Centers". Iaslic1955.org.in. 3 September 1955. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Bengal Library Association". Blacal.org. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- "Pakistan Library Association". Pla.org.pk. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- "Pakistan Librarians Welfare Organization". Librarianswelfare.org. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

- Rowlands, Ian; Nicholas, David; Williams, Peter; Huntington, Paul; Fieldhouse, Maggie; Gunter, Barrie; Withey, Richard; Jamali, Hamid R.; Dobrowolski, Tom; Tenopir, Carol (2008). "The Google generation: the information behaviour of the researcher of the future". ASLIB Proceedings. 60 (4): 290–310. doi:10.1108/00012530810887953.

- Miller, Ellen G. (2009). "Hard Times = A New Brand of Advocacy". Georgia Library Quarterly. 46 (1).

- Isabelle-Constance von Opalinski: Schüsse auf die Zivilisation. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung., (German), 20 August 2014.

- Peter Stone: Monuments Men: protecting cultural heritage in war zones. In: Apollo – The International Art Magazine. 2 Februar 2015.

- Corine Wegener, Marjan Otter: Cultural Property at War: Protecting Heritage during Armed Conflict. In: The Getty Conservation Institute, Newsletter. 23.1, Spring 2008.

- Eden Stiffman: Cultural Preservation in Disasters, War Zones. Presents Big Challenges. In: The Chronicle Of Philanthropy. 11 May 2015.

Further reading

- Barnard, T.D.F. (ed.) (1967). Library Buildings: design and fulfilment; papers read at the Week-end Conference of the London and Home Counties Branch of the Library Association, held at Hastings, 21–23 April 1967. London: Library Association (London and Home Counties Branch)

- Terry Belanger. Lunacy & the Arrangement of Books, New Castle, Del.: Oak Knoll Books, 1983; 3rd ptg 2003, ISBN 978-1-58456-099-9

- Bieri, Susanne & Fuchs, Walther (2001). Bibliotheken bauen: Tradition und Vision = Building for Books: traditions and visions. Basel: Birkhäuser ISBN 3-7643-6429-7

- Ellsworth, Ralph E. (1973). Academic Library Buildings: a guide to architectural issues and solutions. 530 pp. Boulder: Associated University Press

- Fraley, Ruth A. & Anderson, Carol Lee (1985). Library Space Planning: how to assess, allocate, and reorganize collections, resources, and physical facilities. New York: Neal-Schuman Publishers ISBN 0-918212-44-8

- Irwin, Raymond (1947). The National Library Service [of the United Kingdom]. London: Grafton & Co. x, 96 p.

- Lewanski, Richard C. (1967). Lilbrary Directories [and] Library Science Dictionaries, in Bibliography and Reference Series, no. 4. 1967 ed. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Clio Press. N.B.: Publisher also named as the "American Bibliographical Center".

- Robert K. Logan with Marshall McLuhan. The Future of the Library: From Electric Media to Digital Media. New York: Peter Lang Publishing.

- Mason, Ellsworth (1980). Mason on Library Buildings. Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press ISBN 0-8108-1291-6

- Monypenny, Phillip, and Guy Garrison (1966). The Library Functions of the States [i.e. the US]: Commentary on the Survey of Library Functions of the States, [under the auspices of the] Survey and Standard Committee [of the] American Association of State Libraries. Chicago: American Library Association. xiii, 178 p.

- Murray, Suart A.P. (2009). The Library an Illustrated History. New York: Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8389-0991-1.

- Orr, J.M. (1975). Designing Library Buildings for Activity; 2nd ed. London: Andre Deutsch ISBN 0-233-96622-6

- Thompson, Godfrey (1973). Planning and Design of Library Buildings. London: Architectural Press ISBN 0-85139-526-0

- Herrera-Viedma, E.; Lopez-Gijon, J. (2013). "Libraries' Social Role in the Information Age". Science. 339 (6126): 1382. doi:10.1126/science.339.6126.1382-a. PMID 23520092.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Libraries |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Library. |

| Look up library in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Libraries at Curlie

- LIBweb—Directory of library servers in 146 countries via WWW

- Centre for the History of the Book, hss.ed.ac.uk

- Dana, John Cotton (1920). "Libraries, Special, Commercial and Industrial". In Rines, George Edwin (ed.). Encyclopedia Americana.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Library Data". Encyclopedia Americana.

- Rines, George Edwin, ed. (1920). "Library Publications". Encyclopedia Americana.

- Walter, Frank K. (1920). "Rural Libraries". Encyclopedia Americana.

- Tedder, Henry Richard; Brown, James Duff (1911). "Libraries". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.).

- Paton, James Morton; Charles Alexander Nelson; Melvil Dewey; James Hulme Canfield (1905). "Libraries". New International Encyclopedia.

- A Library Primer by John Cotton Dana (1899)

- Champlin, John D. (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.

- Libraries: Frequently Asked Questions, ibiblio.org

- A Library Primer, by John Cotton Dana, 1903, setting out the basics of organizing and running a library. (from Project Gutenberg)