Kilham, Northumberland

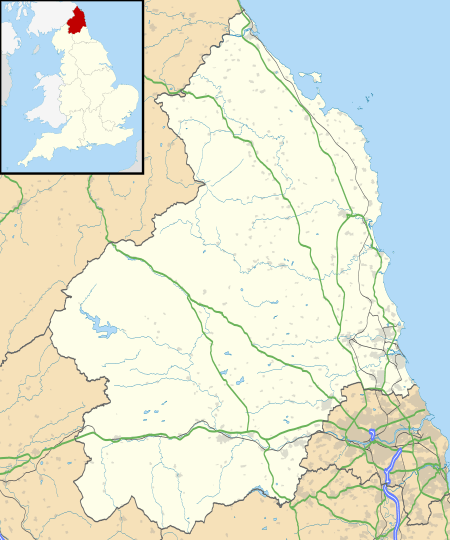

Kilham is a hamlet and civil parish in the English county of Northumberland, located 8.0 miles (12.9 km) west of Wooler, 12.0 miles (19.3 km) east of Kelso, 17.0 miles (27.4 km) south west of Berwick upon Tweed and 38.9 miles (62.6 km) north west of Morpeth. It lies on the northern edge of the Northumberland National Park in Bowmont Valley Northumberland]. The hamlet, which consists of a small group of agricultural dwellings, is overlooked by Kilham Hill and the northern limits of the Cheviot Hills.[1] The parish had a population of 131 in 2001, and includes the hamlets of Howtel and Pawston, along with the former upland township of Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls.[2] falling to less than 100 at the 2011 Census. Details are now included in the parish of Branxton

| Kilham | |

|---|---|

Kilham Valley | |

Kilham Location within Northumberland | |

| Population | 131 (2001) |

| OS grid reference | NT8832 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MINDRUM |

| Postcode district | TD12 |

| Dialling code | 01890 |

| Police | Northumbria |

| Fire | Northumberland |

| Ambulance | North East |

| UK Parliament | |

Situated on the border with Scotland, Kilham had a turbulent history. It suffered from repeated Scottish incursions, and was often destroyed and laid waste. The situation was considered serious enough for a report to be made to the Privy Council of England, about a raid in 1597 which had resulted in the death of several villagers. In later, more peaceful times, the area developed into an agricultural backwater, which was gradually opened up by the construction of roads and railways.

Etymology

Kilham first appears in documents in 1177 as Killum, which is usually thought to derive from the Old English Cylnum, indicating the presence of kilns. The name was still spelt Killum as late as the 18th century.[1]

History

Several well preserved Bronze Age settlements exist in the area around Kilham, and a cairn on Kilham Hill, excavated in 1905, was found to conceal a cist containing burnt bones, thought to date from the period. A bronze rapier blade dating from 1500–1000 BC, found near the Bowmont Water in the 19th century, and now in the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh, provides further evidence of Bronze Age activity in the parish.[3]

Iron Age hillforts are found throughout the Cheviot Hills, and the parish contains examples at Bowmont Hill, Kilham Hill, Pawston Camp, and Wester Hill. Such hillforts were not necessarily defensible, and the small interior area of most suggests they were not permanent settlements. Although some may have served as defended farmsteads, others are likely to have been animal enclosures, market places or places of worship. An enclosure at Barley Hill, in the north of the parish, is considered to have been a small farmstead, consisting of roundhouses and adjacent stockyards.[4]

Towards the end of the first millennium BC, all of the remaining upland forest in the area had been cleared, and increasing numbers of settlements or homesteads were established on the high moorland. Some of these appear to have been built within the ramparts of earlier hillforts, which had been abandoned for some time. A well-preserved settlement at Longknowe is thought to be Romano-British, although this part of Northumberland lay beyond the Roman frontier for much of the period of occupation. Small enclosed homesteads such as this are likely to have continued in use for several centuries, and were probably only abandoned as the population moved to lower lying hamlets during the Early Medieval period.[5]

In 651 King Oswine granted 12 named vills, or townships, including Shotton, and perhaps Thornington, along with a large tract of land beside the Bowmont Water, to Saint Cuthbert.[6] The villagers would have been required to hand over the major proportion of any surplus produce and labour from these communities to the church.[7]

By the 13th century, Kilham formed one of the constituent manors of the barony of Wark on Tweed. The barony had been established by King Henry I, and granted to Walter L'espec, one of his principal agents of government in Northern England. The lord of the manor was Michael of Kilham, although he did not possess the whole township, part being held by Kirkham Priory in North Yorkshire, which had been founded by the barons of Wark. In 1269 it was recorded that the priory had 1,000 sheep feeding on the "great moor" of Kilham.[8] Land at Shotton and Coldsmouth was held by Kelso Abbey in the Scottish Borders.[9] The manorial lordship passed through various hands to the Greys of Chillingham Castle, who eventually consolidated ownership of the whole township, in the 17th century acquiring the former Kirkham Priory holdings, which had earlier been sold by the crown after the dissolution of the Monasteries.[10][11]

A bastle, or fortified farmhouse, was built at the north end of the village in the late 16th or early 17th centuries.[12] Right up to the end of the 16th century, Kilham had suffered repeated Scottish incursions. Every valuation of the village's lands in the 15th century revealed a state of waste and destruction.[13] In 1541 the lack of any defensive structure was criticised by Sir Robert Bowes and Sir Ralph Ellerker, the Border Commissioners, who strongly urged that a tower be built in the village.[14] They also reported on the tower at Howtel, which had been "rased and casten downe" during an invasion in 1497. Howtel Tower is mentioned again by Sir Henry Hadston, who in 1584 reported to Queen Elizabeth I that it was one of a number of towers needing repair.[15] Sir Robert Carey, Lord Warden of the Marches, in 1597 reported to the Privy Council of England:

On the 14th instant, at night, four Scotsmen broke up a poor man's door at Kilham on this march, taking his cattle. The town followed, rescued the goods, sore hurt three of the Scots, and brought them back prisoners. The fourth Scot raised his country meanwhile, and at daybreak 40 horse and foot attacked Kilham, but being resisted by the town, who behaved themselves very honestly, they were driven off and two more were taken prisoners. Whereon the Scots raised Tyvidale (Teviotdale), being near at hand, and to the number of 160 horse and foot came back by seven in the morning, and not only rescued all the prisoners but slew a man, left seven for dead and hurt very sore a great many others.[13]

A map dated 1712 shows two rows of dwellings and toft enclosures in the village. A total of 19 buildings are shown, plus a watermill to the north beside the Bowmont Water, and three buildings to the south west at Longknowe. The village appears to extend slightly further along the lane to Longknowe than the current hamlet.[16] Although not shown on the map, the ruins of an earlier chapel are believed to have existed in Chapel Field, on the hillside to the south east of the village.[17]

By the latter part of the 19th century Kilham consisted of a large farm with farmhouse and two rows of cottages for the farm's workforce. There was, in addition, a smithy and a post office. To the south, Thompson's Walls was by 1800 an estate with a farm complex laid out around a square courtyard. Hemp and flax were grown, and a small mill is shown on maps from the 1860s onwards.[18][19] The adoption of new agricultural techniques and improvements to the area's transport infrastructure resulted in greater prosperity for Kilham's farming community in the late 18th and 19th centuries.[20] Enclosure of common land was intended to increase efficiency, bring more land under the plough, and reduce the high prices of agricultural production, and Howtel Common was enclosed in 1779.[21] Female bondagers, or outworkers, were employed to work in the fields up to the end of the 19th century. The system was recorded in the Scottish Borders as early as 1656, and subsequently spread into Glendale. Agricultural labourers, known as hinds, were required to provide a female, often a relative or a girl living with the hind's family, who would be on call as a day labourer whenever required. The bondager's work was regarded as paying the rent of the hind's cottage.[22][23]

Thomas Henry Scott, a police constable from Pawston, was murdered in 1880, while attempting to arrest two poachers at Hethpool.[24] He had been bludgeoned and beaten.[25]

The Alnwick and Cornhill Railway, owned by the North Eastern Railway, opened in 1887, providing a rail link to Wooler and Cornhill on Tweed. There was no station at Kilham, the nearest being at Mindrum and Kirknewton, but sidings were built to handle goods traffic. Passenger services were withdrawn in 1930, with a goods and parcels service continuing until 1965. Kilham sidings closed in 1953.[26]

Farming at Kilham during most of the 20th century concentrated on rearing pedigree Aberdeen Angus cattle. However, mechanisation and the decline in farming incomes resulted in the farm ceasing to function as an independent unit. In 1988 the Kilham estate was divided into three separate farms: Kilham, Longknowe and Thompson's Walls. Longknowe Farm now specialises in breeding and rearing sheep and suckler cows, while Kilham Farm is leased to a neighbouring farmer at Thornington, and some of the buildings have been converted into workshops.[27][28]

Geography

Kilham stands on the south bank of the Bowmont Water in Glendale, at the mouth of Kilham Burn. Settlement is limited to dispersed farmsteads and small hamlets, of which Kilham is the largest.[29] Glendale has a clearly defined valley floor and pronounced raised terraces. The area is relatively well wooded, with both coniferous plantations and broadleaved woodland on the surrounding hills, and areas of alder woodland and pollarded willow along the valley floor.[30] The river forms part of the River Tweed Site of Special Scientific Interest, designated in 2001 due to its biological interest, and the River Tweed Special Area of Conservation, designated under the European Habitats Directive for the biological interest within the river system.[31]

To the south, the area is dominated by Kilham Hill, 1,109 feet (338 m) high, and above Longknowe, in the valley of Kilham Burn, is the former township of Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls, lying in the northern limits of the Cheviot Hills.[32] The geology of the upland area is composed of Devonian igneous rocks, and the landscape is characterised by smooth rolling hills and extensive plateaux of semi-natural acidic grass moor, known locally as white grass. There are areas of heather moorland and, in wetter parts, blanket bog dominated by dwarf shrubs, sedges, sphagnum moss and cotton grass. Coniferous woodland plantations are common on the upper valley slopes, with the remnants of broadleaved woodland, gorse scrub and meadow grassland in the steep sided valleys. The area reaches a height of 1,358 feet (414 m) at Coldsmouth Hill.[29]

On the opposite side of the dale, to the north, are the hamlets of Howtel and Thornington. Much of this area consists of glacial gravel, and both sand and gravel were extracted at Thornington.[33] Upstream on the Bowmont Water, the former township of Pawston lies to the south west.[32]

Northumberland is the coldest county in England, with mean summer temperatures in the northern lowlands 0.5 °C below those found 60 miles (97 km) to the south. Kilham is sheltered from the prevailing winds, which are from the south west, but there are cold winds from the east in winter. The growing season is between April and November. The low mean temperature and high rainfall result in water-logging of fine textured soils, and leaching of nutrients from soils with a coarser texture.[34] The nearest weather station for which comprehensive records are published is at Boulmer, located 29.8 miles (48.0 km) south east of Kilham, on the North Sea coast.[35]

| Climate data for Boulmer | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.7 (44.1) |

6.9 (44.4) |

8.8 (47.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

12.5 (54.5) |

15.6 (60.1) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

9.3 (48.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

11.8 (53.3) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

1.5 (34.7) |

2.5 (36.5) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.9 (42.6) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.8 (51.4) |

10.8 (51.4) |

9.1 (48.4) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.7 (38.7) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.6 (42.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 59.0 (2.32) |

41.4 (1.63) |

46.7 (1.84) |

49.2 (1.94) |

48.0 (1.89) |

53.4 (2.10) |

47.6 (1.87) |

62.1 (2.44) |

54.7 (2.15) |

58.1 (2.29) |

67.2 (2.65) |

63.6 (2.50) |

651 (25.62) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 11.4 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 8.8 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 9.0 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 10.8 | 11.9 | 10.8 | 118.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 62.6 | 79.4 | 121.5 | 152.7 | 194.1 | 193.8 | 186.3 | 178.9 | 135.6 | 105.7 | 76.5 | 53.3 | 1,540.4 |

| Source: The Met Office[36] | |||||||||||||

Governance

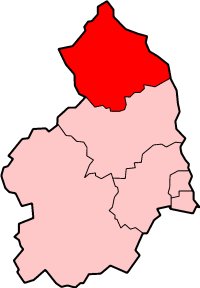

Kilham, Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls, Howtel and Pawston were four of 15 townships in the ancient parish of Kirknewton, one of the largest parishes in England.[37][38] Following the Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, parishes were grouped into unions: Glendale Poor Law Union was created in 1837.[39] Under the Public Health Act 1848 the area of the poor law union became Glendale Rural Sanitary District, which from 1889 formed a second tier of local government under Northumberland County Council.[40] The four townships became civil parishes in their own right, separate from Kirknewton but within the sanitary district, in 1866, and under the Local Government Act 1894 became part of Glendale Rural District.[39][41] Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls, Howtel and Pawston were amalgamated into Kilham in 1955.[42] Glendale Rural District was abolished in 1974, and became part of the newly created Borough of Berwick upon Tweed, which was in turn abolished as a result of the Northumberland (Structural Change) Order 2008, under which Northumberland became a unitary authority in 2009.[43]

Kilham now forms part of Wooler electoral division of Northumberland County Council, represented by Anthony Murray of the Conservative Party, who was elected to the new council on its creation in 2008.[44] The parish does not have a parish council.[45]

Since 1885, Kilham has been part of Berwick upon Tweed parliamentary constituency. It has been represented by Sir Alan Beith, the deputy leader of the Liberal Democrats, since he won a by-election in 1973.[46]

Public services

Water and sanitation are provided by Northumbrian Water, owned since 2011 by Hong Kong-based Cheung Kong Infrastructure Holdings.[47][48] Water supplies come from an aquifer, and are abstracted by boreholes.[49] The electricity distribution company serving Kilham is Northern Powergrid, formerly known as CE Electric, which is owned by Berkshire Hathaway, a multinational conglomerate based in Nebraska.[50][51][52][53]

The North East Ambulance Service, formed in 2006, provides ambulance and paramedic services, operating out of the ambulance station at Wooler.[54] The general provision of health services is the responsibility of Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.[55] The nearest hospital is Berwick Infirmary in Berwick upon Tweed, which has a 24-hour minor injuries service.[56]

Law enforcement is the responsibility of Northumbria Police, the sixth largest police force in England and Wales, which was formed in 1974 by the merger of Northumberland Constabulary and part of Durham Constabulary. The local neighbourhood team is based at the police station in Berwick upon Tweed.[57][58][59]

Northumberland Fire and Rescue Service, a division of Northumberland County Council, provides public protection services, operating out of the fire station at Wooler.[60] A search and rescue service is provided by the Northumberland National Park Mountain Rescue Team and North of Tyne Search and Rescue Team.[61][62]

Demography

Kilham had a population of 131 in 2001, of which 13.7 per cent were below the age of 16, and 11.5 per cent were over 64 years of age.[2][63] Owner occupiers inhabited 13.7 per cent of the dwellings, and 61.6 per cent were rented. Holiday homes accounted for a further 12.3 per cent of dwellings, and 12.3 per cent were vacant.[64] The proportion of households without use of a vehicle was 5.2 per cent, but 34.5 per cent had two or more. The population was predominantly white: 94.8 per cent identified themselves as such.[65]

| Population change in Kilham | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1801 | 1811 | 1821 | 1831 | 1841 | 1851 | 1861 | 1871 | 1881 | 1891 |

| Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls | 32 | 49 | 44 | 41 | 38 | 20 | 30 | 25 | 15 | 8 |

| Howtel | 186 | 130 | 190 | 195 | 191 | 196 | 141 | 114 | 118 | 116 |

| Kilham | 206 | 252 | 246 | 217 | 279 | 258 | 209 | 210 | 156 | 143 |

| Pawston | 135 | 180 | 209 | 207 | 199 | 208 | 189 | 181 | 172 | 170 |

| Total | 559 | 611 | 689 | 660 | 707 | 682 | 569 | 530 | 461 | 437 |

| Year | 1901 | 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 2001 | |||

| Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls | 9 | 12 | 6 | 16 | 10 | |||||

| Howtel | 95 | 90 | 86 | 109 | 75 | |||||

| Kilham | 113 | 116 | 135 | 139 | 83 | 185 | 131 | |||

| Pawston | 125 | 143 | 106 | 110 | 80 | |||||

| Total | 342 | 361 | 333 | 374 | 248 | 185 | 131 | |||

| [66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76] | ||||||||||

Economy

Agriculture has been an important part of Kilham's life for centuries. As early as the 13th century sheep farming had been developed on the moorland, and in 1269 it was recorded that Kirkham Priory had 1,000 sheep on the "great moor" of Kilham.[8] Shepherds often lived in shielings, temporary summer settlements high in the hills.[20] Hemp and flax were grown, and Aberdeen Angus cattle reared.[18][27] The high hills and moors of Northumberland are ideal for grazing cattle and sheep, and some of England's tastiest beef and lamb is produced.[77]

In the 19th century, the upland areas were increasingly used for shooting wild gamebirds. The great landowners would hold large organised shooting parties for their friends, employing local farm workers as beaters. Gamekeepers were responsible for looking after the birds before they were shot, and for breeding pheasants in special shelters.[20] Arable farming was more important in the north of the parish, and was aided by increased mechanisation and improved transport links.[78] Andesite was quarried for use as a building material, and sand and gravel extracted.[33][79]

At the 2001 census, 72.0 per cent of Kilham's population were in employment; the unemployment rate was 5.6 per cent. Of those employed, 54.5 per cent worked in service industries, while 46.8 per cent were in extractive and manufacturing industries. The average distance travelled to work was 14.9 miles (24.0 km).[80]

Landmarks

Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls

Now almost unpopulated, Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls lies 1.7 miles (2.7 km) south west of Kilham in the northern reaches of the Cheviot Hills. Coldsmouth Hill, 1,358 feet (414 m) high, is the highest point in the parish. Two Bronze Age burial cairns crown the summit. A flint knife, bronze dagger and cremated bone were discovered during excavations in 1929.[81][82] South of the hill St Cuthbert's Way, a 62 miles (100 km) long-distance trail, passes on its route from Melrose to Holy Island.[79] Remains of a Romano-British village, on the north west slopes of the hill, include five enclosures containing the circular foundations of buildings.[83] Nearby, Ring Chesters is an Iron Age hillfort. The enclosure contains the circular stone foundations of at least eight huts, two of which contain traces of what may be hearths.[84] In the saddle between the two hills, the remains of the medieval settlement of Heddon, first recorded in 1296, contain the sites of at least six longhouses, which are each divided into two rooms. The village overlies an earlier Romano-British enclosed settlement.[85]

Thompson's Walls consists of two 19th-century farm cottages and a group of farm buildings, notable for being built entirely of hard, igneous rock.[86] Andesite was quarried, and was used in the construction of Yetholm church.[79]

Howtel

Howtel is situated 1.5 miles (2.4 km) north east of Kilham, to the north of the Bowmont Water. The name is thought to mean Low Ground with a Wood, and the area has a number of ancient camps and settlements shown on early Ordnance Survey maps. The remains of a peel tower, which was partly destroyed in 1496, stand in the centre of the hamlet. The walls are over 6.6 feet (2.0 m) thick.[15][87]

Bowmont House, a former Scottish Presbyterian chapel and manse, is on the Kilham road, to the south of the hamlet. The building dates from 1850, and is rendered, with ashlar dressings and a Welsh slate roof.[88]

Kilham

Many of the buildings in Kilham date back to the 19th century, and the stone construction is typical of Northumbrian farms in the 1850s.[27] Locally quarried dark igneous andesite and granite were mainly used, although sandstone was brought in from the east for higher status buildings.[29] Kilham House was transformed from a traditional farmhouse into a small country house by a substantial extension built in 1926. The appearance was enhanced by the use of identical 12-pane windows throughout.[89]

The old mill pond above the hamlet has been restored by the Northumberland National Park Authority. Blackbirds, wrens and thrushes are often seen in the hedge banks along the lane to Longknowe, and the roadside verges contain a colourful variety of flowering plants, including dog roses, St John's wort, stitchwort and bloody cranesbill. Nearby is a sheepwash, where Kilham's shepherds increased the value of the fleeces by washing their sheep's wool before it was clipped.[27]

On the slopes of Kilham Hill are the remains of a shieling, which provided shelter for shepherds watching over the sheep as they grazed. In summer the hillside is a profusion of purple and blue as wild thyme, cross-leaved heath and harebells come into bloom; foxgloves have colonised the stony ground. A stone cairn crowns the summit, and was found to conceal a Bronze Age cist containing burnt bones. From the summit, there are views over the Milfield Plain, Glendale and the Till Valley, and to Eildon Hill, Yeavering Bell and the Cheviot Hills. Buzzards, kestrels, lapwings and curlews are common, while bilberry, tormentil and heath bedstraw carpet the soil.[27]

North of the hamlet, the trackbed of the former Alnwick and Cornhill Railway forms part of a walk along the Bowmont Water, where kingfishers, grey herons, oystercatchers and mallards can be seen. Sedge warblers are regular visitors in summer, and short-eared owls hunt in the nearby tree plantation.[27] On the northern bank of the river, Reedsford Farm has a 17th-century dovecote.[90]

Pawston

Pawston lies 2.3 miles (3.7 km) west of Kilham on the south bank of the Bowmont Water. It was the site of the deserted medieval village of Thornington, first recorded in 1296.[91] To the north east of Pawston House are single storey shelter sheds and a two-storey granary, dating from the 18th century. An old beam forms a continuous bressumer over the door and two windows, and the building has a steeply pitched Scottish slate roof.[92] South of the house is a 17th-century sundial base decorated with foliage, grotesque heads and festoons.[93] John Selby, a "gentleman dwelling at Pawston", was killed in 1596 while defending his home against Scottish marauders.[94] Pawston Hill has the remains of an Iron Age settlement.[95] The locally rare wood carpet moth was found at Pawston Lake in 1929, and a number of nationally or locally scarce plants are also present, including the autumnal water starwort, blunt leaved pondweed, gypsywort, maiden pink and shoreweed.[96][97]

Shotton Farm, immediately north of the Scottish border, marks the site of large medieval hamlet, first recorded in 1296.[98] A document from 1541 records that it had been laying waste for more than 30 years.[99] Shotton House was built in 1828, and has an ashlar facade and Scottish slate roof. Above the panelled door is a Tuscan entablature showing the year of construction and the original owner's name.[100] The nearby gatepiers have Greek decoration, and were added in 1829.[101]

The Rising of the North in 1569 was an attempt to depose Queen Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. Thomas Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, one of its leaders, was betrayed while seeking shelter at Harelaw. The current Harelaw House was built in 1593.[102] It stands below Hare Law, 912 feet (278 m) high, on which are the remains of a hillfort.[103]

Transport

Kilham lies on the B6351 road between Akeld and Mindrum. The B6352 runs north east through Howtel to Ford, where it connects with the A697.[104] A bus service is provided only on Wednesdays. Service 266 has two morning journeys operated by Glen Valley Tours, and runs a circular Wooler–Akeld–Kirknewton–Kilham–Flodden–Milfield–Akeld–Wooler route.[105]

The road from Wooler through Kirknewton and Kilham to the Scottish border was converted into a turnpike by the early 19th century. In 1812 the Ford and Lowick Turnpike Trust took over responsibility for the road from Milfield through Flodden, Howtel, Kilham, Langham and Shotton to the border, and in 1834 the deviation through Thornington was included. With reduced income from tolls due to competition from the new railways, the turnpike trusts were gradually wound up in the late 19th century, and responsibility for highways taken over by Northumberland County Council after its creation in 1889.[106]

From the 1860s onwards, various schemes were promoted to build a railway line, either through Glendale or over the Milfield Plain. In 1881 the Central Northumberland Railway was proposed, linking Newcastle upon Tyne with Ponteland, Rothbury, Wooler and Kelso. The threat posed by the proposal spurred the North Eastern Railway to put forward a branch line of its own between Alnwick, Wooler and Cornhill on Tweed. The company was strongly supported by the tradespeople of Alnwick, who were concerned at the loss of business if the farmers of Glendale had a direct raillink to the rival market and shops in Rothbury. Both schemes were presented to Parliament in 1881, and it was the North Eastern Railway's route which gained approval, with the Alnwick and Cornhill Act passed in 1882. The single-track line opened on 5 September 1887, having cost £272,267 to build. From Wooler, it ran through Kirknewton and Kilham to Mindrum, before turning north to Cornhill on Tweed, where it joined the line from Tweedmouth to Kelso. There was no station at Kilham, but sidings were built to handle goods traffic.[26]

The North Eastern Railway was amalgamated into the London and North Eastern Railway in 1923 and, just 43 years after the line opened, passenger trains were withdrawn in 1930, the new owners claiming that passenger numbers had declined due to competition from buses. A goods and parcels service continued, but on 12 August 1948 torrential rain caused severe flooding, damaging the bridge over the Bowmont Water between Mindrum and Kilham. For a while the line operated as two separate lines with termini at Mindrum and Kirknewton, but further flooding in October 1949 destroyed the bridge at Ilderton. Rather than rebuild the bridge British Railways, which had taken over the line the previous year, repaired the bridge at Mindrum, restoring services from the north through to Wooler. Goods services were withdrawn from Kilham sidings in 1953, and the remaining northern part of the line to Wooler finally closed on 29 March 1965.[26]

Apart from a short heritage line, the Heatherslaw Light Railway, operating between Heatherslaw and Etal, the nearest railway station is at Berwick upon Tweed, 17.0 miles (27.4 km) to the north east on the East Coast Main Line between London and Edinburgh.[107] Services are provided by the London North Eastern Railway and CrossCountry.[108] Chathill, 25.2 miles (40.6 km) east of Kilham, has a limited commuter service to Newcastle upon Tyne, operated by Northern.[109]

Education

A national school for 60 children opened at Howtel in 1875.[15] Primary education to the age of nine is now provided by Wooler First School, which had 101 pupils in 2007, and is located in Wooler, 8.0 miles (12.9 km) to the east. It was last inspected by Ofsted in 2007.[110]

Children aged from nine to 13 attend Glendale Middle School, also located in Wooler, which had 150 pupils when it was last inspected in 2010. The school has specialist status as a Technology College, holds the Sportsmark and Healthy Schools awards, and has a "partner school" in China.[111]

At the age of 13, pupils transfer to Berwick Academy, formerly Berwick Community High School, in Berwick upon Tweed, 17 miles (27 km) north east of Kilham.[112] As a high school, it was inspected in 2007 when it had 922 pupils, including 174 in the sixth form.[113] The academy has specialist status as both a Business and Enterprise College and as an applied learning college. In 2009 it was awarded High Performing Specialist School status, and holds a Healthy Schools award.[114]

Culture

Robert Story, known as "the Craven Poet", was born at Wark on Tweed in 1795. His father was an agricultural labourer, and the family moved frequently around the Northumberland villages. When just 10 years old, Story ran away to accompany a lame fiddler on an excursion through the Scottish Borders for a month, and about a year later the family moved to Howtel, where Story attended the local school. He later claimed that this was where "I learned nearly all that I ever learned from a Master—namely to read badly, to write worse, and to cipher a little farther, perhaps than to the Rule of Three." There he was introduced to Divine Songs for Children, and discovered a love of poetry while reading on the hills, where he was employed as a shepherd. By 1820 he had moved to Gargrave in North Yorkshire where he opened a school, and in 1825 published a volume of poetry, Craven Blossoms. Algernon Percy, the Duke of Northumberland, became a patron in 1857 and financed an edition of his works. In 1859 Story was invited to Ayr for the centenary celebrations of Robert Burns, where he recited his poem on Burns. The Bradfordian considered that "he stands high among the minor poets of Great Britain, and many of his sweet lyrics will most assuredly descend to and be highly admired by posterity, and by none more than Yorkshiremen."[115][116][117]

A ten-minute DVD postcard, The Cheviot Hills from Dawn till Dusk, shows the scene across five Cheviot valleys, including Kilham, set to the music On Cheviot Hills by Alistair Anderson. The film shows the changing moods as the day progresses, and was produced by Shadowcat Films, with support from the Northumberland National Park Authority.[118][119][120]

Linda Scott-Robinson is a painter living in Howtel. She paints local landscapes and states that her inspiration comes from the ever-shifting light that constantly changes the surrounding landscape. She is a member of Network Artists, an independent association of professional artists living and working in Northumberland.[121][122]

Inglenook Sidings is an award-winning model railway train shunting puzzle created by Alan Wright for the Manchester Model Railway Society's 1978 show, based on the former Kilham Sidings on the Alnwick and Cornhill Railway.[123] The aim of the puzzle is to create a train consisting of five of the eight wagons sitting in the sidings, in the order in which the wagons are randomly selected.[124]

A local saying in Northumberland was "to take Hector's cloak", meaning to deceive a friend who relies on your loyalty. The saying referred to the betrayal of Sir Thomas Percy, the Earl of Northumberland, by Hector Armstrong of Harelaw. The earl, a loyal Roman Catholic, had been one of the leaders of the Rising of the North in 1569, an attempt to depose Queen Elizabeth I and replace her with Mary, Queen of Scots. The rebels captured Barnard Castle and advanced on York but, with little popular support and facing overwhelming government forces, fled north, towards Scotland. The earl sought shelter in Armstrong's house at Harelaw, but was betrayed to James Douglas, the Earl of Morton, the regent of Scotland. The Scots subsequently sold him to the English government for £2,000, and he was beheaded at York, refusing an offer to save his life by renouncing Catholicism.[125][126]

Religion

Although an early chapel is believed to have existed in Kilham, the local parish church, dedicated to Saint Gregory the Great, is at Kirknewton. The site has been used for Christian worship since the 11th century, and the present church dates from the 12th century. It was restored in 1860.[17][127][128] A Scottish Presbyterian chapel, with seating for 350 worshippers, was built at Howtel in 1850, although this is no longer in use.[15]

Sport

Fellwalking is a popular pastime in the Cheviot Hills, and Coldsmouth Hill is a favoured destination, with excellent views in all directions, and two large burial cairns on its summit. It is most easily climbed from Halterburn in Yetholm.[129] St Cuthbert's Way, a 62 miles (100 km) long-distance trail, passes to the south of the hill on its route from Melrose to Holy Island.[79] Kilham Hill can be ascended from the Kilham Valley or the Kirknewton road east of Kilham.[27]

The Northumbria Hang Gliding and Paragliding Club, based in Newcastle upon Tyne, organises both hang gliding and paragliding at Coldsmouth Hill, which works in an easterly or west north westerly wind, and Longknowe, which works best in a west north westerly wind.[130][131]

References

- "Kilham, Northumberland". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Census 2001: Parish Headcounts: Berwick upon Tweed". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- "Kilham: Bronze Age (2000 BC–700 BC)". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Kilham: Iron Age (700 BC–AD 70)". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Kilham: Romano-British Period and After". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Early Medieval Glendale". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Shires and the Concept of the Multiple Estate". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Kirkham Priory's Lands". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- Barrow, G W S (2003). The Kingdom of the Scots: Government, Church and Society from the Eleventh to the Fourteenth Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-7486-1803-3.

- "The Barony of Wark and Manor of Kilham". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Kilham : Mills". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Kilham Stronghouse". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- "Kilham: Border Warfare". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- Bowes, Sir Robert; Ellerker, Sir Ralph (1541). "A View and Survey of the Borders or Frontier of the East and Middle Marches of England". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

Kylhame: Most part Gray of Chillingham's inheritance. No fortresse, desolate therefore by warre. Pytye, being a good plot. The towneshippe of Kylham conteyneth xxvi husband lands nowe well penyshed and hathe in yt nether tower, barmekyn nor other fortresse whiche ys great petye for yt woulde susteyne many able men for defence of those borders yf yt had a tower and barmekyn buylded in yt where nowe yt lyeth waste in ev'ry warre and then yt is a great tyme after (before) yt can be replenished againe and the most parte thereof ys the inherytaunce of the said Mr Graye of Chyllingham.

- "Howtel". Northumberland Communities. Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Kilham: The Village Layout". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- "Kilham: The Chapel". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- "Kilham: Later History". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Kilham: Farm Mills". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Period Overview: Post Medieval". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Enclosure Awards". Northumberland Collections Service. Northumberland County Council. December 2008. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Bondagers". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 29 August 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Glendale Local History Society". Wooler: Gateway to Glendale and the Cheviot Hills. Glendale Gateway Trust. Archived from the original on 19 April 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Northumberland Winter Assizes 1881: The Queen Against John Tait and William Blyth: Murder: Brief for Prosecution". Northumberland Communities: Kirknewton. Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Northumbria Police". National Police Officers Roll of Honour and Remembrance. Police Roll of Honour Trust. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "The Alnwick and Cornhill Railway". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Kilham Longknowe Farm Walk" (PDF). Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Kilham in the 20th Century". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Cheviot Area: Introduction to the Study Area". Traditional Boundaries. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 12 December 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Final Report to Tynedale District Council and Northumberland National Park Authority" (PDF). A Landscape Character Assessment of Tynedale District and Northumberland National Park. Julie Martin Associates. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 July 2010. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- Bissett, Nicola; Comins, Luke; Seal, Kate (2010). "Tweed Catchment Management Plan". Tweed Forum. p. 38. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Kilham: Area of Study". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 20 October 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "The Geology of Part of Northumberland, Including the Country Between Wooler and Coldstream". Internet Archive. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "The Topography and Climate of Northumberland National Park" (PDF). Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 January 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Synoptic and Climate Stations". The Met Office. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Boulmer 1971–2000 Averages". The Met Office. Archived from the original on 16 September 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Kirknewton Civil Parish: Unit History and Boundary Changes". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Kilham, Northumberland: An Archaeological and Historical Study of a Border Township" (PDF). The Archaeological Practice. 2004. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Glendale Poor Law Union: Unit History and Boundary Changes". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Glendale Rural Sanitary District: Unit History and Boundary Changes". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 18 September 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Glendale Rural District: Unit History and Boundary Changes". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Kilham Civil Parish: Unit History and Boundary Changes". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "The Northumberland (Structural Change) Order 2008". The National Archives. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Councillors: Committee Membership". Your Council. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Parish and Town Councils". Your Council. Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Berwick upon Tweed: The 2010 General Election". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- "Welcome to Northumbrian Water Group". Northumbrian Water. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Our Areas of Supply: North East England" (PDF). Northumbrian Water. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Final Water Resources Management Plan: 2010–2035" (PDF). Northumbrian Water. January 2010. p. 26. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- "About Us". Northern Powergrid. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "History". Mid American Energy Holdings Company. Archived from the original on 4 July 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Berkshire Hathaway". Berkshire Hathaway. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Business Activities" (PDF). 2010 Annual Report. Berkshire Hathaway. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Who We Are and What We Do". North East Ambulance Service. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Welcome to Northumberland Care Trust". Northumberland NHS Care Trust. Archived from the original on 14 October 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Berwick Infirmary: General Information". Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "About Us". Northumbria Police Authority. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "History". Northumbria Narpo. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "What's Going on in Your Area: Berwick". Northumbria Police Authority. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Local Fire Stations". Northumberland County Council. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "North East Search and Rescue Association". Mountain Rescue England and Wales. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "The Area We Cover". North of Tyne Search and Rescue Team. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Census 2001: Parish Profile: People: Kilham". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Census 2001: Parish Profile: Accommodation and Tenure: Kilham". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Census 2001: Parish Profile: Households: Kilham". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Enumeration Abstract: 1801: County of Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Observations and Enumeration Abstract: 1811: County of Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Observations, Enumeration and Parish Register Abstracts: 1821: County of Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Comparative Account of the Population: 1831: County of Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Enumeration Abstract: 1841: County of Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Population Tables: England and Wales: 1861: Northern Counties: Northumberland". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Population Tables: England and Wales: Registration Counties: 1871: Northern Counties". Online Historical Population Reports. University of Essex. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Historical Statistics: Population: Coldsmouth and Thompson's Walls". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Historical Statistics: Population: Howtel". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Historical Statistics: Population: Kilham". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Historical Statistics: Population: Pawston". A Vision of Britain Through Time. University of Portsmouth. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Your Countryside on a Plate". Farming. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 15 February 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Local History: Kilham". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Young, Robert; Frodsham, Paul; Hedley, Iain; Speak, Steven. "Resource Assessment, Research Agenda and Research Strategy" (PDF). An Archaeological Research Framework for Northumberland National Park. Northumberland National Park Authority. p. 367. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Census 2001: Parish Profile: Work and Qualifications: Kilham". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Coldsmouth Hill". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Coldsmouth Hill Ring Cairn". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Coldsmouth Hill Roman Period Village". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Ring Chesters Defended Settlement". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Heddon". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- "Thompson's Walls". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Howtel Tower House". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Bowmont House". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Young, Robert; Frodsham, Paul; Hedley, Iain; Speak, Steven. "Resource Assessment, Research Agenda and Research Strategy" (PDF). An Archaeological Research Framework for Northumberland National Park. Northumberland National Park Authority. p. 331. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2011. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Dovecote at Reedsford Farm". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Pawston". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Farmbuildings circa 60 Yards North East of Pawston House". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Sundial Base circa 30 Yards South of Pawston Old House". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "A History of Northumberland: Issued Under the Direction of Northumberland County History Committee". Internet Archive. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Pawston Hill Camp". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Dunn, Tom C; Parrack, Jim D (1987). "Wood Carpet". The Moths and Butterflies of Northumberland and Durham. Archived from the original on 3 August 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Metherell, Chris (2011). "North Northumberland: Scarce, Rare and Extinct Vascular Plant Register" (PDF). Chris Metherell. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Shotton". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Shotton". Keys to the Past. Northumberland County Council. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Shotton House". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Gatepiers and Walls circa 40 Yards North East of Shotton House". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Harelaw Cottages". Harelaw Cottages. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- Parson, William; White, William (1828). History, Directory and Gazetteer of the Counties of Durham and Northumberland. Newcastle upon Tyne: W White and Company. p. 515. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

kilham northumberland.

- "Election Maps: Northumberland". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Wooler–Kirknewton–Wooler: Circular: 266" (PDF). Glen Valley Tours. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Kilham: Transport and Communications". Historic Village Atlas. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 22 October 2007. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Welcome to Heatherslaw". Heatherslaw Light Railway Company. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Stations: Berwick upon Tweed". National Rail Enquiries. Train Information Services. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Stations: Chathill". National Rail Enquiries. Train Information Services. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Wooler First School: Inspection Report". Ofsted. 19 April 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Glendale Middle School: Inspection Report". Ofsted. 8 July 2010. Archived from the original on 5 August 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Daniel, Brian (6 June 2011). "Berwick High School Head Responds to Parents' Fears". The Journal. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Berwick Community High School: Inspection Report". Ofsted. 13 July 2007. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Berwick upon Tweed Community High School: Prospectus" (PDF). Berwick upon Tweed Community High School. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Sketch of the Life of Robert Story". The Bradfordian: 8–9. 1 October 1860. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Vincent, David (1982). Bread, Knowledge and Freedom: A Study of Nineteenth Century Working Class Autobiography (University Paperback ed.). London: Methuen and Company. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-416-34670-1. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- Story, Robert (1857). "Preface". The Poetical Works of Robert Story. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans and Roberts. p. v. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

howtel.

- "The Cheviot Hills". Shadowcat Films. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Welcome to Shadowcat Films". Shadowcat Films. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Case Study: Shadowcat Films". Grants, Support and Advice. Northumberland National Park Authority. Archived from the original on 15 March 2012. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- "Linda Scott-Robinson: The Artist". Linda Scott-Robinson. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Members: Linda Scott-Robinson". Network Artists. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Inglenook Sidings". Model Railways Shunting Puzzles. Adrian Wymann. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Inglenook Sidings: Rules and Operation". Model Railways Shunting Puzzles. Adrian Wymann. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- Denham, Aislabie (1858). Folk-lore or a Collection of Local Rhymes, Proverbs, Sayings, Prophecies, Slogans etc Relating to Northumberland, Newcastle upon Tyne and Berwick upon Tweed. Richmond: Ebor. p. 21.

- "Blessed Thomas Percy". New Advent. Kevin Knight. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- "Saint Gregory the Great, Kirknewton". Wooler: Gateway to Glendale and the Cheviot Hills. Glendale Gateway Trust. Archived from the original on 10 September 2011. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Glendale Churches Heritage Trail". Google. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Coldsmouth Hill". Corbetteer. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "Coldsmouth Hill". Paragliding Earth. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "The Cheviots". Aero Site Guide. Archived from the original on 12 March 2012. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

External links

![]()