Eurasian oystercatcher

The Eurasian oystercatcher (Haematopus ostralegus) also known as the common pied oystercatcher, or palaearctic oystercatcher,[2] or (in Europe) just oystercatcher, is a wader in the oystercatcher bird family Haematopodidae. It is the most widespread of the oystercatchers, with three races breeding in western Europe, central Eurosiberia, Kamchatka, China, and the western coast of Korea. No other oystercatcher occurs within this area. The extinct Canary Islands oystercatcher (Haematopus meadewaldoi), formerly considered a distinct species, may have actually been an isolated subspecies or distinct population of the Eurasian oystercatcher.[3]

| Eurasian oystercatcher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Haematopodidae |

| Genus: | Haematopus |

| Species: | H. ostralegus |

| Binomial name | |

| Haematopus ostralegus | |

| |

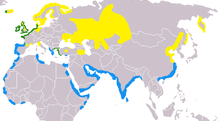

| Range of H. ostralegus Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range | |

This oystercatcher is the national bird of the Faroe Islands.

Description

The oystercatcher is one of the largest waders in the region. It is 40–45 cm (16–18 in) long, the bill accounting for 8–9 cm (3–3 1⁄2 in), and has a wingspan of 80–85 cm (31–33 in).[4] They are obvious and noisy plover-like birds, with black and white plumage, red legs and strong broad red bills used for smashing or prising open molluscs such as mussels or for finding earthworms.[4] Despite its name, oysters do not form a large part of its diet. The bird still lives up to its name, as few if any other wading birds are capable of opening oysters at all.

This oystercatcher is unmistakable in flight, with white patches on the wings and tail, otherwise black upperparts, and white underparts. Young birds are more brown, have a white neck collar and a duller bill. The call is a distinctive loud piping.

The bill shape varies; oystercatchers with broad bill tips open molluscs by prising them apart or hammering through the shell, whereas pointed-bill birds dig up worms. Much of this is due to the wear resulting from feeding on the prey. Individual birds specialise in one technique or the other which they learn from their parents.[4]

Subspecies

There are three subspecies: the nominate ostralegus found in Europe and the coasts of eastern Europe, longipes from Central Asia and Russia, and osculans found from Kamchatka in the Russian Far East and northern parts of China. The extinct Canarian oystercatcher from the Canary Islands may have represented a fourth subspecies, meadewoldi.

Bill length shows clinal variation with an increase from west to east. The subspecies longipes has distinctly brownish upperparts and the nasal groove extends more than halfway along the bill. In the subspecies ostralegus the nasal groove stops short of the half-way mark. The osculans subspecies lacks white on the shafts of the outer 2–3 primaries and has no white on the outer webs of the outer five primaries.[5]

Ecology

The oystercatcher is a migratory species over most of its range. The European population breeds mainly in northern Europe, but in winter the birds can be found in north Africa and southern parts of Europe. Although the species is present all year in Ireland, Great Britain and the adjacent European coasts, there is still migratory movement: the large flocks that are found in the estuaries of south-west England in winter mainly breed in northern England or Scotland. Similar movements are shown by the Asian populations. The birds are highly gregarious outside the breeding season.

The nest is a bare scrape on pebbles, on the coast or on inland gravelly islands. 2–4 eggs are laid. Both eggs and chicks are highly cryptic.

Because of its large numbers and readily identified behaviour, the oystercatcher is an important indicator species for the health of the ecosystems where it congregates. Extensive long-term studies have been carried out on its foraging behaviour, in northern Germany, in the Netherlands and particularly on the River Exe estuary in south-west England.[6] These studies form an important part of the foundation for the modern discipline of behavioural ecology.

Etymology

The scientific name Haematopus ostralegus comes from the Greek haima αἳμα (blood), pous πούς (foot) and the Latin ostrea (oyster) and legere (to collect or pick).[7]

The name oystercatcher was coined by Mark Catesby in 1731 as a common name for the North American species H. palliatus, described as eating oysters.[8] Yarrell in 1843 established this as the preferred term, replacing the older name Sea Pie.[8]

Gallery

Parent on right and juvenile on left on a small beach in Helsinki, Finland in June

Parent on right and juvenile on left on a small beach in Helsinki, Finland in June

Four adults in flight (Hamburger Hallig, North Frisia)

Four adults in flight (Hamburger Hallig, North Frisia).jpg) Heligoland

Heligoland_in_flight_(juv_middle).jpg)

_in_flight.jpg) large flock in Morocco

large flock in Morocco Eurasian oystercatcher in flight

Eurasian oystercatcher in flight

References

- BirdLife International (2015). "Haematopus ostralegus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Eurasian Oystercatcher". Avibase.

- "Extinct Canary Island bird was not a unique species after all, DNA tests prove". phys.org. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- The Birds of the Western Palearctic (Abridged ed.). Oxford University Press. 1997. ISBN 0-19-854099-X.

- Hayman, Peter; Marchant, John; Prater, Tony (1986). Shorebirds: An Identification Guide to the Waders of the World. London: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0395602379.

- Goss-Custard, J. D. (Ed.) (1996). The Oystercatcher: From individuals to populations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198546474

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 184, 286. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Lockwood, W.B. (1993). The Oxford Dictionary of British Bird Names. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866196-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haematopus ostralegus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Haematopus ostralegus |

- "Eurasian oystercatcher media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Oystercatcher WEBCAM live from the roof of the University of Bergen

- Pirates of the Caribbean, a movie that features the bird

- BirdLife species factsheet for Haematopus ostralegus

- "Haematopus ostralegus". Avibase.

- Eurasian oystercatcher photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Audio recordings of Eurasian oystercatcher on Xeno-canto.