Seersucker

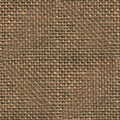

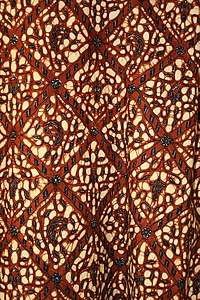

Seersucker or railroad stripe is a thin, puckered, all-cotton fabric, commonly striped or chequered, used to make clothing for spring and summer wear. The word came into English from Hindi, and originates from Sanskrit क्षीरशर्करा (kshirsharkara) and also Persian words شیر shîr and شکر shakar, literally meaning "milk and sugar", from the resemblance of its smooth and rough stripes to the smooth texture of milk and the bumpy texture of sugar.[1] Seersucker is woven in such a way that some threads bunch together, giving the fabric a wrinkled appearance in places. Often realized by warp threads for the puckered bands during weaving being fed at a greater rate than the warp threads of the smooth stripes (these need not be, but often are, of different colors). This feature causes the fabric to be mostly held away from the skin when worn, facilitating heat dissipation and air circulation. It also means that pressing is not necessary.

Common items made from seersucker include suits, shorts, shirts, curtains, dresses, and robes. The most common colors for it are white and blue; however, it is produced in a wide variety of colors, usually alternating colored stripes and puckered white stripes slightly wider than pin stripes.

History

During the British colonial period, seersucker was a popular material in Britain's warm-weather colonies like British India. When seersucker was first introduced in the United States, it was used for a broad array of clothing items. For suits, the material was considered a mainstay of the summer wardrobe of gentlemen, especially in the South, who favored the light fabric in the high heat and humidity of the southern climates, especially prior to the arrival of air conditioning.[2]

During the American Civil War, this cheap but durable material was used to make haversacks and even the famous baggy pants of Confederate Zouaves such as the Louisiana Tigers.[3] From the mid Victorian era until the early 20th century, seersucker was also known as bed ticking due to its widespread use in mattresses, pillow cases and nightshirts during the hot summers in the Southern US[4] and Britain's overseas colonies.[5]

The fabric was originally worn by the poor in the U.S. until preppy undergraduate students began wearing it in the 1920s in an air of reverse snobbery.[6]

Seersucker's comfort and easy laundering made it the choice of Captain Anne A. Lentz, one of the first female officers selected to run the Marine Corps Women's Reserve during the Second World War,[7] for the summer service uniforms of the first female United States Marines. From the 1940s onwards, nurses and US hospital volunteers also wore uniforms made from a type of red and white seersucker known as candy stripe.[8]

Hickory stripe

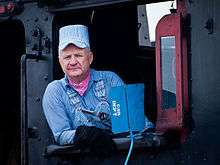

In the days of the Old West, a type of heavyweight indigo or navy blue seersucker known as "hickory stripe" was used to make the overalls, work jackets and peaked caps of train engineers and railroad workers such as George "Stormy" Kromer or Casey Jones.[9] It was later worn by butchers[10] and employees of the gasoline companies, most notably Standard Oil.[11] This cotton fabric was durable like denim, cheap to produce, kept the wearer cool in the hot cab of the steam locomotive,[2] and obscured oilstains. Even today, the uniforms of American Union Pacific[12] train drivers include "railroad stripe" caps based on those from the steam age, and some rolling stock used for freight, shunting and maintenance work is painted with blue and white "zebra stripes" to improve visibility.[13]

In fashion

About 1909, New Orleans clothier Joseph Haspel, Sr. started making men's suits out of seersucker fabric, which soon became regionally popular as more comfortable and practical than other types of suits and fit the hot and humid southern climate.[14][15]

During the 1950s, cheap railroad stripe overalls were worn by many young boys until they were old enough to wear jeans. This coincided with the popularity of train sets, and films such as The Great Locomotive Chase. At the same time, seersucker formal wear continued to be worn by many professional adults in the Southern and Southwestern US.[16] College professors were known to favor full suits with red bowties, although 1950s Ivy League and 21st century preppy[17] students usually restricted themselves to a single seersucker garment,[18] such as a blazer paired with khaki chino trousers.[19] Menswear brands famous for manufacturing seersucker at this time included Brooks Brothers, Macy's, Sears, and Joseph Haspel of New Orleans.[2][20]

In the 1970s, seersucker pants were popular among young urban African Americans seeking to connect to their rural heritage.[21] The fabric made a comeback among teenage girls in the 1990s, and again in the 2010s.[22]

Beginning in 1996, the US Senate held a Seersucker Thursday in June, where the participants dress in traditionally Southern clothing,[23] but the tradition was discontinued in June 2012. As of June 2014, it has been revived by members of the US Senate.[24]

The Republican Party has advised students at its Comms college not to wear seersucker when appearing before the cameras because of its old fashioned connotations,[2] plus the disruptive effect of the stripes.[25]

2010 to present

From 2012 onwards, seersucker blazers and pants made a comeback among American men[26] due to a resurgence of interest in preppy clothing[27] and the 1920s fashion showcased in the 2013 film version of The Great Gatsby. Although pale blue and dark blue stripes remained the most popular choice, alternative colors included green, red, black,[28] grey, beige, yellow, orange,[29] purple, pink, and brown.[30] The traditional two button blazer was updated with a slimmer cut and Edwardian inspired lapel piping,[31] and double breasted jackets became available during the mid 2010s.[32] Since 2010, "Seersucker Social" events have been held in major cities across the United States, where participants wear vintage clothes and ride vintage bicycles.[33] Such events are the summer equivalent of a Tweed Run, which is traditionally held in the fall.

In the 2016 Olympics hosted by Brazil, the Australian Olympic team received green and white seersucker blazers[34] and Toms Shoes rather than the traditional dark green with gold trim.[35] At the same time, seersucker pants, skirts, espadrilles, blouses, and even bikinis were worn as casual attire by many fashion conscious young women in America.[36]

Weaving process

Seersucker is made by slack-tension weave. The threads are wound onto the two warp beams in groups of 10 to 16 for a narrow stripe. The stripes are always in the warp direction and on grain. Today, seersucker is produced by a limited number of manufacturers. It is a low-profit, high-cost item because of its slow weaving speed.[37]

Gallery

Green/white checkered seersucker fabric

Green/white checkered seersucker fabric- Shirt from green/white seersucker fabric

Blue/white striped seersucker fabric

Blue/white striped seersucker fabric Green/white striped seersucker fabric

Green/white striped seersucker fabric- David Ferriero, speaking at Wikimania 2012, wearing a seersucker suit

Members of the United States Senate on Seersucker Day 2019.

Members of the United States Senate on Seersucker Day 2019.

References

- "The American Heritage Dictionary entry: seersucker". The American Heritage Dictionary (Fourth ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

- McKay, Brett; McKay, Kate (30 April 2015). "How to Wear a Seersucker Suit". The Art of Manliness. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Troiani, Don; Coates, Earl J.; McAfee, Michael J. (2006). Don Troiani's Civil War Zouaves, Chasseurs, Special Branches, and Officers. Stackpole Books – via Google Books.

- Basso, Hamilton (3 November 1947). "The Roosevelt Legend". LIFE. Time Inc. p. 142 – via Google Books.

- "The Atlantic Monthly". The Atlantic. Vol. 18. Atlantic Monthly Company. January 1866 – via Google Books.

- Colman, David (20 April 2006). "Summer Cool of a Different Stripe". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- "The Army Nurse Corp". WW2 US Medical Research Centre. Archived from the original on 23 February 2009. Retrieved 14 March 2009.

- Brayley, Martin (20 February 2012). "World War II Allied Nursing Services". Bloomsbury Publishing – via Google Books.

- Russell, Tim (2007). Fill 'er Up!. Voyageur Press – via Google Books.

- Devine, J. P. (3 July 2015). "All hail the man in the seersucker suit". Central Maine. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Workers of the Writers' Program of the Works Progress Administration in the State of Arizona (1940). Arizona, the Grand Canyon State: A State Guide. Best Books on – via Google Books.

- "The Origin of the Blue and White Striped Engineer's Cap". Union Pacific Railroad Museum. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Gustafson, Randy; Sing, John (November 2004). "Santa Fe Zebra Stripe FM H12-44 in N Scale". Archived from the original on 30 September 2015. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Mazur, Jacqueline (21 April 2016). "The history of the seersucker suit begins right here in New Orleans". WGNO. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Taylor, Jessica (11 June 2015). "#TBT A Brief History Of (Political) Seersucker". NPR. Retrieved 7 June 2017.

- Hunter, Cecilia Aros; Hunter, Leslie Gene (2000). Texas A&M University Kingsville. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0738508810 – via Google Books.

- Schneider, Adam P. (11 April 2007). "Suck It, Seersucker!". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Green, Dennis (15 July 2015). "The big problem with seersucker is that guys have been wearing it all wrong". Business Insider. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Marcus, Lilit (23 June 2010). "How to Wear Seersucker Properly If You Are Not Actually Southern". The Gloss. Archived from the original on 6 July 2016. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- Brasted, Chelsea (5 February 2014). "Haspel family wants to make seersucker cool again, relaunches its iconic brand". The Times-Picayune. NOLA. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Ebony,". Ebony. Vol. 24 no. 11. Johnson Publishing Company. September 1969 – via Google Books.

- Kruspe, Dana (10 April 2014). "Trendspotting: Railroad Stripes". Fashionista. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Davis, Jess (22 June 2007). "Stuffy Senate smiles at seersucker suits". Scripps Howard Foundation Wire. Retrieved 13 April 2015.

- Schwab, Nikki (11 June 2015). "Trent Lott Just Can't Resist a 'Seersucker Thursday'". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Hamby, Peter (15 October 2014). "Inside the GOP's secret school". CNN Politics. Retrieved 19 August 2016.

- "9. Seersucker". AskMen. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Summer Pants Pick: Nautica Pants, Seersucker Pants". AskMen. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "When Can I Wear a Seersucker Suit?". Men's Health. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Genevieve. "How to Wear a Seersucker Suit". TheIdleMan. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- Corsillo, Liza (11 June 2015). "How to Wear a Seersucker Suit, According to the Brand That Invented Them". GQ. Condé Nast. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- "Style Essentials #6: Blazers & Suits | Nautical Blazer Pick: Tallia Orange Seersucker Sportcoat". AskMen. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Brooks Bros jacket". AskMen. Archived from the original on 12 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Nania, Rachel (11 June 2015). "Parasols, picnics and pedaling: A dandy weekend for the Seersucker Social". WTOP. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- Browning, Jennifer (29 March 2016). "Australia releases 'retro candy stripe' Rio Olympics uniform". ABC News. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- "Sportscraft unveils 2016 Opening Ceremony uniform". Official Site of the 2016 Australian Olympic Team. Australian Olympic Committee. 30 March 2016. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Wilson, Julee (21 May 2015). "How To Wear Seersucker Without Looking Like You're At A Country Club". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 April 2016.

- Poland, Tom (2019). The Last Sunday Drive: Vanishing Traditions in Georgia and the Carolinas. Charleston: The History Press. p. 109.

External links

.svg.png)