Calendering (textiles)

Calendering of textiles is a finishing process used to smooth, coat, or thin a material. With textiles, fabric is passed between calender rollers at high temperatures and pressures. Calendering is used on fabrics such as moire to produce its watered effect and also on cambric and some types of sateens.

In preparation for calendering, the fabric is folded lengthwise with the front side, or face, inside, and stitched together along the edges.[1][2] The fabric can be folded together at full width, however this is not done as often as it is more difficult.[2] The fabric is then run through rollers that polish the surface and make the fabric smoother and more lustrous.[3] High temperatures and pressure are used as well.[2][4] Fabrics that go through the calendering process feel thin, glossy and papery.[2]

The wash durability of a calendared finish on thermoplastic fibers like polyester is higher than on cellulose fibers such as cotton. On blended fabrics such as Polyester/Cotton the durability depends largely on the proportion of synthetic fiber component present as well as the amount and type of finishing additives used and the machinery and process conditions employed.

Variations

Several different finishes can be achieved through the calendering process by varying different parts. The main different types of finishes are beetling, watered, embossing, and Schreiner.[5]

Beetled

Beetling is a finish given to cotton and linen cloth, and makes it look like satin. In the beetling process the fabric goes over wooden rollers and is beaten with wooden hammers.[5]

Watered

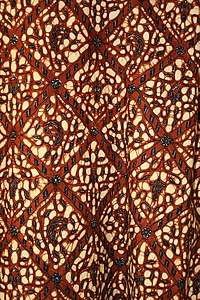

The watered finish, also known as moire, is produced by using ribbed rollers. These rollers compress the cloth and the ribs produce the characteristic watermark effect by moving aside threads as well as compressing them.[2][3] This leaves some of the threads round while others get compressed and become flat.[5]

Embossed

In the embossing process the rollers have engraved patterns on them, and the patterns become stamped onto the fabric.[5] The end result is a raised or sunken pattern, depending on the roller.[6] This works best with soft fabrics.[5]

Schreiner

Similar to the watered process, in the Schreiner process the rollers are ribbed, only in the Schreiner process the ribs are very fine, with as many as six hundred ribs per inch under extremely high pressure. The threads are pressed flat with little lines in them, which causes the fabric to reflect the light better than a flat surface would. Cloth finished with the Schreiner method has a very high lustre, which is made more lasting by heating the rollers.[5]

History

Historically calendering was done by hand with a huge pressing stone. For example in China huge rocks were brought from the north of the Yangtze River. The pressing stone was cut into a bowl shape, and the surface of the curved bottom made perfectly smooth. After a piece of cloth was placed underneath the stone the worker would stand on the stone and rock it with his two feet in order to press the cloth.[7]

See also

References

- Harmuth, Louis (1915). Dictionary of Textiles. Fairchild publishing company. p. 106. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Textile World Record. Lord & Nagle Co. 1907. p. 118. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Cresswell, Lesley; Lawler, Barbara; Wilson, Helen; Watkins, Susanna (2002). Textiles Technology. Heinemann. p. 36. ISBN 0-435-41786-X. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Paine, Melanie (1999). Fabric Magic. Frances Lincoln ltd. p. 24. ISBN 0-7112-0995-2. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Nystrom, Paul Henry (1916). Textiles. D. Appleton. pp. 274–275. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Alexander, Theadora; et al. (2002). "Clothing and Textiles: Fabric Finishes". Caribbean Home Economics in Action, Book 3. Heinemann. p. 129. ISBN 0-435-98048-3. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- Chao, Kang (1977). The Development of Cotton Textile Production in China. East Asian Research Center, Harvard University. p. 34. ISBN 0674200217.

.svg.png)