Isle of Skye

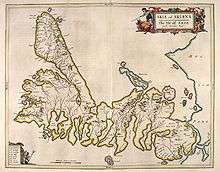

The Isle of Skye,[8] commonly known as Skye (/skaɪ/; Scottish Gaelic: An t-Eilean Sgitheanach or Eilean a' Cheò), is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland.[Note 1] The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous centre dominated by the Cuillin, the rocky slopes of which provide some of the most dramatic mountain scenery in the country.[10][11] Although it has been suggested that Sgitheanach describes a winged shape there is no definitive agreement as to the name's origins.

| Gaelic name | An t-Eilean Sgitheanach[1] |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [əɲ ˈtʲʰelan ˈs̪kʲi.anəx] ( |

| Norse name | Skíð |

| Meaning of name | Etymology unclear |

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1353645.jpg) Bank Street, Portree | |

| Location | |

| |

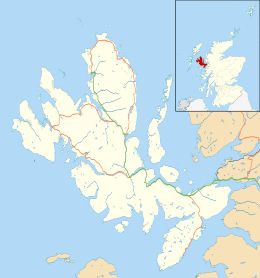

Isle of Skye Isle of Skye shown within Scotland | |

| OS grid reference | NG452319 |

| Coordinates | 57.307°N 6.230°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Skye |

| Area | 1,656 km2 (639 sq mi)[2] |

| Area rank | 2[3] [4] |

| Highest elevation | Sgùrr Alasdair, 993 m (3,258 ft)[5] |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Highland |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 10,008[6] |

| Population rank | 4[6] [4] |

| Population density | 6.04/km2 (15.6/sq mi)[2][6] |

| Largest settlement | Portree |

| References | [7] |

The island has been occupied since the Mesolithic period, and its history includes a time of Norse rule and a long period of domination by Clan MacLeod and Clan Donald. The 18th century Jacobite risings led to the breaking up of the clan system and later clearances that replaced entire communities with sheep farms, some of which involved forced emigrations to distant lands. Resident numbers declined from over 20,000 in the early 19th century to just under 9,000 by the closing decade of the 20th century. Skye's population increased by 4 per cent between 1991 and 2001.[12] About a third of the residents were Gaelic speakers in 2001, and although their numbers are in decline, this aspect of island culture remains important.[13]

The main industries are tourism, agriculture, fishing and forestry. Skye is part of the Highland Council local government area. The island's largest settlement is Portree, which is also its capital,[14] known for its picturesque harbour.[15] There are links to various nearby islands by ferry and, since 1995, to the mainland by a road bridge. The climate is mild, wet and windy. The abundant wildlife includes the golden eagle, red deer and Atlantic salmon. The local flora are dominated by heather moor, and there are nationally important invertebrate populations on the surrounding sea bed. Skye has provided the locations for various novels and feature films and is celebrated in poetry and song.

Etymology

The first written references to the island are Roman sources such as the Ravenna Cosmography, which refers to Scitis[16] and Scetis, which can be found on a map by Ptolemy.[17] One possible derivation comes from skitis, an early Celtic word for winged, which may describe how the island's peninsulas radiate out from a mountainous centre.[18] Subsequent Gaelic-, Norse- and English-speaking peoples have influenced the history of Skye; the relationships between their names for the island are not straightforward. Various etymologies have been proposed, such as the "winged isle" or "the notched isle"[19] but no definitive solution has been found to date; the place name may be from an earlier, non-Gaelic language.[20][21]

In the Norse sagas Skye is called Skíð, for example in the Hákonar saga Hákonarsonar[22] and a skaldic poem in the Heimskringla from c. 1230 contains a line that translates as "the hunger battle-birds were filled in Skye with blood of foemen killed".[23] The island was also referred to by the Norse as Skuy (misty isle),[18] Skýey or Skuyö (isle of cloud).[1] The traditional Gaelic name is An t-Eilean Sgitheanach (the island of Skye), An t-Eilean Sgiathanach being a more recent and less common spelling. In 1549 Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, wrote of "Sky": "This Ile is callit Ellan Skiannach in Irish, that is to say in Inglish the wyngit Ile, be reason it has mony wyngis and pointis lyand furth fra it, throw the dividing of thir foirsaid Lochis."[Note 2] but the meaning of this Gaelic name is unclear.[25]

Eilean a' Cheò, which means island of the mist (a translation of the Norse name), is a poetic Gaelic name for the island.[19][Note 3]

Geography

At 1,656 square kilometres (639 sq mi), Skye is the second-largest island in Scotland after Lewis and Harris. The coastline of Skye is a series of peninsulas and bays radiating out from a centre dominated by the Cuillin hills (Gaelic: An Cuiltheann). Malcolm Slesser suggested that its shape "sticks out of the west coast of northern Scotland like a lobster's claw ready to snap at the fish bone of Harris and Lewis"[10] and W. H. Murray, commenting on its irregular coastline, stated that "Skye is sixty miles [100 km] long, but what might be its breadth is beyond the ingenuity of man to state".[1][Note 4] Martin Martin, a native of the island, reported on it at length in a 1703 publication. His geological observations included a note that:

There are marcasites black and white, resembling silver ore, near the village Sartle: there are likewise in the same place several stones, which in bigness, shape, &c., resemble nutmegs, and many rivulets here afford variegated stones of all colours. The Applesglen near Loch-Fallart has agate growing in it of different sizes and colours; some are green on the outside, some are of a pale sky colour, and they all strike fire as well as flint: I have one of them by me, which for shape and bigness is proper for a sword handle. Stones of a purple colour flow down the rivulets here after great rains.

— Martin Martin, A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland.[27]

The Black Cuillin, which are mainly composed of basalt and gabbro, include twelve Munros and provide some of the most dramatic and challenging mountain terrain in Scotland.[10] The ascent of Sgùrr a' Ghreadaidh is one of the longest rock climbs in Britain and the Inaccessible Pinnacle is the only peak in Scotland that requires technical climbing skills to reach the summit.[18][28] Nearby Sgùrr Alasdair, meanwhile, is the tallest mountain on any Scottish island. These hills make demands of the hill walker that exceed any others found in Scotland[29] and a full traverse of the Cuillin ridge may take 15–20 hours.[30] The Red Hills (Gaelic: Am Binnean Dearg) to the east are also known as the Red Cuillin. They are mainly composed of granite that has weathered into more rounded hills with many long scree slopes on their flanks. The highest point of these hills is Glamaig, one of only two Corbetts on Skye.[31]

The northern peninsula of Trotternish is underlain by basalt, which provides relatively rich soils and a variety of unusual rock features. The Kilt Rock is named after the columnar structure of the 105 metres (344 ft) cliffs, said to resemble the pleats in a kilt.[32] The Quiraing is a spectacular series of rock pinnacles on the eastern side of the main spine of the peninsula and further south is the rock pillar of the Old Man of Storr.[33] The view of the Quiraing and the Old Man of Storr is one of the most iconic in all of Scotland, and is frequently used on calendars and tourism guides and brochures.

Beyond Loch Snizort to the west of Trotternish is the Waternish peninsula, which ends in Ardmore Point's double rock arch. Duirinish is separated from Waternish by Loch Dunvegan, which contains the island of Isay. The loch is ringed by sea cliffs that reach 295 metres (967 ft) at Waterstein Head. Oolitic loam provides good arable land in the main valley. Lochs Bracadale and Harport and the island of Wiay lie between Duirinish and Minginish, which includes the narrower defiles of Talisker and Glen Brittle and whose beaches are formed from black basaltic sands.[34] Strathaird is a relatively small peninsula close to the Cuillin hills with only a few crofting communities,[35] the island of Soay lies offshore. The bedrock of Sleat in the south is Torridonian sandstone, which produces poor soils and boggy ground, although its lower elevations and relatively sheltered eastern shores enable a lush growth of hedgerows and crops.[36] The islands of Raasay, Rona, Scalpay and Pabay all lie to the north and east between Skye and the mainland.[1][18]

Towns and villages

Portree in the north at the base of Trotternish is the largest settlement (estimated population 2,264 in 2011)[37] and is the main service centre on the island. Broadford, the location of the island's only airstrip, is on the east side of the island and Dunvegan in the north-west is well known for its castle and the nearby Three Chimneys restaurant. The 18th-century Stein Inn on the Waternish coast is the oldest pub on Skye.[38] Kyleakin is linked to Kyle of Lochalsh on the mainland by the Skye Bridge, which spans the narrows of Loch Alsh. Uig, the port for ferries to the Outer Hebrides, is on the west of the Trotternish peninsula and Edinbane is between Dunvegan and Portree.[18] Much of the rest of the population lives in crofting townships scattered around the coastline.[39]

Climate

The influence of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf Stream create a mild oceanic climate. Temperatures are generally cool, averaging 6.5 °C (43.7 °F) in January and 15.4 °C (59.7 °F) in July at Duntulm in Trotternish.[40][Note 5] Snow seldom lies at sea level and frosts are less frequent than on the mainland. Winds are a limiting factor for vegetation. South-westerlies are the most common and speeds of 128 km/h (80 mph) have been recorded. High winds are especially likely on the exposed coasts of Trotternish and Waternish.[42] In common with most islands of the west coast of Scotland, rainfall is generally high at 1,500–2,000 mm (59–79 in) per annum and the elevated Cuillin are wetter still.[42] Variations can be considerable, with the north tending to be drier than the south. Broadford, for example, averages more than 2,870 mm (113 in) of rain per annum.[43] Trotternish typically has 200 hours of bright sunshine in May, the sunniest month.[44] On 28 December 2015, the temperature reached 15 °C, beating the previous December record of 12.9 °C, set in 2013. On 9 May 2016, a temperature of 26.7 °C (80.1 °F) was recorded at Lusa in the south-east of the island.[45]

| Climate data for Duntulm, Skye | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

16.7 (62.1) |

22.3 (72.1) |

26.7 (80.1) |

24.5 (76.1) |

25.9 (78.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

26.7 (80.1) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.5 (43.7) |

6.6 (43.9) |

8.1 (46.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

12.4 (54.3) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.4 (59.7) |

15.7 (60.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.1 (48.4) |

7.6 (45.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.3 (37.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

6.5 (43.7) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.4 (50.7) |

10.7 (51.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

7.2 (45.0) |

5.1 (41.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

6.2 (43.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −4.0 (24.8) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−4.1 (24.6) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

0.0 (32.0) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

2.6 (36.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 148 (5.84) |

100 (3.93) |

82 (3.24) |

86 (3.40) |

73 (2.87) |

85 (3.35) |

97 (3.83) |

112 (4.41) |

128 (5.05) |

152 (6.00) |

143 (5.63) |

142 (5.58) |

1,350 (53.13) |

| Source 1: Cooper (1983)[40] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Met office for May and December record high,[46] bing weather [47] | |||||||||||||

History

Prehistory

A Mesolithic hunter-gatherer site dating to the 7th millennium BC at An Corran in Staffin is one of the oldest archaeological sites in Scotland. Its occupation is probably linked to that of the rock shelter at Sand, Applecross, on the mainland coast of Wester Ross where tools made of a mudstone from An Corran have been found. Surveys of the area between the two shores of the Inner Sound and Sound of Raasay have revealed 33 sites with potentially Mesolithic deposits.[48][49] Finds of bloodstone microliths on the foreshore at Orbost on the west coast of the island near Dunvegan also suggest Mesolithic occupation. These tools probably originate from the nearby island of Rùm.[50]

Rubha an Dùnain, an uninhabited peninsula to the south of the Cuillin, has a variety of archaeological sites dating from the Neolithic onwards. There is a 2nd or 3rd millennium BC chambered cairn, an Iron Age promontory fort and the remains of another prehistoric settlement dating from the Bronze Age nearby. Loch na h-Airde on the peninsula is linked to the sea by an artificial "Viking" canal that may date from the later period of Norse settlement.[51][52] Dun Ringill is a ruined Iron Age hill fort on the Strathaird peninsula, which was further fortified in the Middle Ages and may have become the seat of Clan MacKinnon.[53]

Early history

The late Iron Age inhabitants of the northern and western Hebrides were probably Pictish, although the historical record is sparse.[54] Three Pictish symbol stones have been found on Skye and a fourth on Raasay.[55] More is known of the kingdom of Dál Riata to the south; Adomnán's life of Columba, written shortly before 697, portrays the saint visiting Skye (where he baptised a pagan leader using an interpreter[56]) and Adomnán himself is thought to have been familiar with the island.[57] The Irish annals record a number of events on Skye in the later 7th and early 8th centuries – mainly concerning the struggles between rival dynasties that formed the background to the Old Irish language romance Scéla Cano meic Gartnáin.[58]

The Norse held sway throughout the Hebrides from the 9th century until after the Treaty of Perth in 1266. However, apart from placenames, little remains of their presence on Skye in the written or archaeological record. Apart from the name "Skye" itself, all pre-Norse placenames seem to have been obliterated by the Scandinavian settlers.[59] Viking heritage is claimed by Clan MacLeod and Norse tradition is celebrated in the winter fire festival at Dunvegan, during which a replica Viking long boat is set alight.[60]

Clans and Scottish rule

The most powerful clans on Skye in the post–Norse period were Clan MacLeod, originally based in Trotternish, and Clan Macdonald of Sleat. Following the disintegration of the Lordship of the Isles, Clan Mackinnon also emerged as an independent clan, whose substantial landholdings in Skye were centred on Strathaird.[61] Clan MacNeacail also have a long association with Trotternish,[62] and in the 16th century many of the MacInnes clan moved to Sleat.[63] The MacDonalds of South Uist were bitter rivals of the MacLeods, and an attempt by the former to murder church-goers at Trumpan in retaliation for a previous massacre on Eigg, resulted in the Battle of the Spoiling Dyke of 1578.[64]

After the failure of the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, Flora MacDonald became famous for rescuing Prince Charles Edward Stuart from the Hanoverian troops. Although she was born on South Uist her story is strongly associated with their escape via Skye and she is buried at Kilmuir in Trotternish.[65] Samuel Johnson and James Boswell's visit to Skye in 1773 and their meeting with Flora MacDonald in Kilmuir is recorded in Boswell's The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. Boswell wrote, "To see Dr Samuel Johnson, the great champion of the English Tories, salute Miss Flora MacDonald in the isle of Sky, [sic] was a striking sight; for though somewhat congenial in their notions, it was very improbable they should meet here".[66] Johnson's words that Flora MacDonald was "A name that will be mentioned in history, and if courage and fidelity be virtues, mentioned with honour" are written on her gravestone.[67] After this rebellion the clan system was broken up and Skye became a series of landed estates.[68]

Of the island in general, Johnson observed:

I never was in any house of the islands, where I did not find books in more languages than one, if I staid long enough to want them, except one from which the family was removed. Literature is not neglected by the higher rank of the Hebrideans. It need not, I suppose, be mentioned, that in countries so little frequented as the islands, there are no houses where travellers are entertained for money. He that wanders about these wilds, either procures recommendations to those whose habitations lie near his way, or, when night and weariness come upon him, takes the chance of general hospitality. If he finds only a cottage he can expect little more than shelter; for the cottagers have little more for themselves but if his good fortune brings him to the residence of a gentleman, he will be glad of a storm to prolong his stay. There is, however, one inn by the sea-side at Sconsor, in Sky, where the post-office is kept.

Skye has a rich heritage of ancient monuments from this period. Dunvegan Castle has been the seat of Clan MacLeod since the 13th century. It contains the Fairy Flag and is reputed to have been inhabited by a single family for longer than any other house in Scotland.[70] The 18th-century Armadale Castle, once home of Clan Donald of Sleat, was abandoned as a residence in 1925 but now hosts the Clan Donald Centre.[71] Nearby are the ruins of two more MacDonald strongholds, Knock Castle, and Dunscaith Castle (called "Fortress of Shadows"), the legendary home of warrior woman, martial arts instructor (and, according to some sources, Queen) Scáthach.[18][72] Caisteal Maol, a fortress built in the late 15th century near Kyleakin and once a seat of Clan MacKinnon, is another ruin.[53]

Clearances

In the late 18th century the harvesting of kelp became a significant activity[75] but from 1822 on cheap imports led to a collapse of this industry throughout the Hebrides.[76] During the 19th century, the inhabitants of Skye were also devastated by famine and Clearances. Thirty thousand people were evicted between 1840 and 1880 alone, many of them forced to emigrate to the New World.[2][77] For example, the settlement of Lorgill on the west coast of Duirinish was cleared on 4 August 1830. Every crofter under the age of seventy was removed and placed on board the Midlothian on threat of imprisonment, with those over that age being sent to the poorhouse.[78] The "Battle of the Braes" involved a demonstration against a lack of access to land and the serving of eviction notices. The incident involved numerous crofters and about 50 police officers. This event was instrumental in the creation of the Napier Commission, which reported in 1884 on the situation in the Highlands. Disturbances continued until the passing of the 1886 Crofters' Act and on one occasion 400 marines were deployed on Skye to maintain order.[79] The ruins of cleared villages can still be seen at Lorgill, Boreraig and Suisnish in Strath Swordale,[78][80] and Tusdale on Minginish.[74][81]

Overview of population trends

| Year | 1755 | 1794 | 1821 | 1841 | 1881 | 1891 | 1931 | 1951 | 1961 | 1971 | 1981 | 1991 | 2001 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population[6][18][82] | 11,252 | 14,470 | 20,827 | 23,082 | 16,889 | 15,705 | 9,908 | 8,537 | 7,479 | 7,183 | 7,276 | 8,847 | 9,232 | 10,008 |

As with many Scottish islands, Skye's population peaked in the 19th century and then declined under the impact of the Clearances and the military losses in the First World War. From the 19th century until 1975 Skye was part of the county of Inverness-shire but the crofting economy languished and according to Slesser, "Generations of UK governments have treated the island people contemptuously."[83] a charge that has been levelled at both Labour and Conservative administrations' policies in the Highlands and Islands.[84][Note 6] By 1971 the population was less than a third of its peak recorded figure in 1841. However, the number of residents then grew by over 28 per cent in the thirty years to 2001.[18]

The changing relationship between the residents and the land is evidenced by Robert Carruthers's remark circa 1852 that, "There is now a village in Portree containing three hundred inhabitants." Even if this estimate is inexact the population of the island's largest settlement has probably increased sixfold or more since then.[37] During the period the total number of island residents has declined by 50 per cent or more.[18][Note 7]

The island-wide population increase of 4 per cent between 1991 and 2001 occurred against the background of an overall reduction in Scottish island populations of 3 per cent for the same period.[12] By 2011 the population had risen a further 8.4% to 10,008[6] with Scottish island populations as a whole growing by 4% to 103,702.[88]

Gaelic

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | An t-Eilean Sgitheanach | |

| Pronunciation: | [əɲ ˈtʲʰelan ˈs̪kʲi.anəx] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Am Binnean Dearg | |

| Pronunciation: | [əm ˈpiɲan ˈtʲɛɾak] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | An Corran | |

| Pronunciation: | [əŋ ˈkʰɔrˠan] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | An Cuan Sgìth | |

| Pronunciation: | [ən̪ˠ ˈkʰuən s̪kʲiː] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | An Tìr, an Cànan 's na Daoine | |

| Pronunciation: | [ən̪ˠ ˈtʲʰiːɾʲ əŋ ˈkʰanan s̪nə ˈtɯːɲə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eilean a' Cheò | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈelan ə ˈçɔː] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Loch na h-Àirde | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈl̪ˠɔx nə ˈhaːrˠtʲə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Mac na Mara | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈmaxk nə ˈmaɾə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Poit Dhubh | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈpʰɔʰtʲ ˈɣu] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Pràban na Linne | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈpʰɾaːpan nə ˈʎiɲə] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Tè Bheag nan Eilean | |

| Pronunciation: | [tʲʰeˈvek nə ˈɲelan] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Sgiathan | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈs̪kʲiəhən] ( | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Sgitheanach | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈs̪kʲi.anəx] ( | |

Historically, Skye was overwhelmingly Gaelic-speaking, but this changed between 1921 and 2001. In both the 1901 and 1921 censuses, all Skye parishes were more than 75 per cent Gaelic-speaking. By 1971, only Kilmuir parish had more than three quarters Gaelic speakers while the rest of Skye ranged between 50 and 74 per cent. At that time, Kilmuir was the only area outside the Western Isles that had such a high proportion of Gaelic speakers.[89] In the 2001 census Kilmuir had just under half Gaelic speakers, and overall, Skye had 31 per cent, distributed unevenly. The strongest Gaelic areas were in the north and south-west of the island, including Staffin at 61 per cent. The weakest areas were in the west and east (e.g. Luib 23 per cent and Kylerhea 19 per cent). Other areas on Skye ranged between 48 per cent and 25 per cent.[89]

Government and politics

In terms of local government, from 1975 to 1996, Skye, along with the neighbouring mainland area of Lochalsh, constituted a local government district within the Highland administrative area. In 1996 the district was included into the unitary Highland Council, (Comhairle na Gàidhealtachd) based in Inverness and formed one of the new council's area committees.[91][92] Following the 2007 elections, Skye now forms a four-member ward called Eilean a' Cheò; it is currently represented by two independents, one Scottish National Party, and one Liberal Democrat councillor.[92]

Skye is in the Highlands and Islands electoral region and comprises a part of the Skye, Lochaber and Badenoch constituency of the Scottish Parliament, which elects one member under the first past the post basis to represent it. Kate Forbes is the current MSP for the SNP.[93] In addition, Skye forms part of the wider Ross, Skye and Lochaber constituency, which elects one member to the House of Commons in Westminster. The present MP Member of Parliament is Ian Blackford of the Scottish National Party, who took office after the SNP's sweep in the General Election of 2015. Prior to this, Charles Kennedy, a Liberal Democrat, had represented the area since the 1983 general election.[90]

Economy

The largest employer on the island and its environs is the public sector, which accounts for about a third of the total workforce, principally in administration, education and health. The second largest employer in the area is the distribution, hotels and restaurants sector, highlighting the importance of tourism. Key attractions include Dunvegan Castle, the Clan Donald Visitor Centre, and The Aros Experience arts and exhibition centre in Portree.[94] There are about a dozen large landowners on Skye, the largest being the public sector, with the Scottish Government owning most of the northern part of the island.[95][96] Glendale is a community-owned estate in Duirinish and the Sleat Community Trust, the local development trust, is active in various regeneration projects.[97][98][99]

Small firms dominate employment in the private sector. The Talisker Distillery, which produces a single malt whisky, is beside Loch Harport on the west coast of the island. Three other whiskies—Mac na Mara ("son of the sea"), Tè Bheag nan Eilean ("wee dram of the isles") and Poit Dhubh ("black pot")—are produced by blender Pràban na Linne ("smugglers den by the Sound of Sleat"), based at Eilean Iarmain.[100][101] These are marketed using predominantly Gaelic-language labels. The blended whisky branded as "Isle of Skye" is produced not on the island but by the Glengoyne Distillery at Killearn north of Glasgow, though the website of the owners, Ian Macleod Distillers Ltd., boasts a "high proportion of Island malts" and contains advertisements for tourist businesses in the island. There is also an established software presence on Skye, with Portree-based Sitekit having expanded in recent years.[102]

Crofting is still important, but although there are about 2,000 crofts on Skye only 100 or so are large enough to enable a crofter to earn a livelihood entirely from the land.[103] Cod and herring stocks have declined but commercial fishing remains important, especially fish farming of salmon and shellfish such as scampi.[104] The west coast of Scotland has a considerable renewable energy potential and the Isle of Skye Renewables Co-op has recently bought a stake in the Ben Aketil wind farm near Dunvegan.[105][106] There is a thriving arts and crafts sector.[107]

The unemployment rate in the area tends to be higher than in the Highlands as a whole, and is seasonal in nature, in part due to the impact of tourism. The population is growing and in common with many other scenic rural areas in Scotland, significant increases are expected in the percentage of the population aged 45 to 64 years.[108]

Transport

Skye is linked to the mainland by the Skye Bridge, while ferries sail from Armadale on the island to Mallaig, and from Kylerhea to Glenelg. Ferries also run from Uig to Tarbert on Harris and Lochmaddy on North Uist, and from Sconser to Raasay.[18][109]

The Skye Bridge opened in 1995 under a private finance initiative and the high tolls charged (£5.70 each way for summer visitors) met with widespread opposition, spearheaded by the pressure group SKAT (Skye and Kyle Against Tolls). On 21 December 2004 it was announced that the Scottish Executive had purchased the bridge from its owners and the tolls were immediately removed.[110]

Bus services run to Inverness and Glasgow, and there are local services on the island, mainly starting from Portree or Broadford. Train services run from Kyle of Lochalsh at the mainland end of the Skye Bridge to Inverness, as well as from Glasgow to Mallaig from where the ferry can be caught to Armadale.[111]

The Isle of Skye Airfield at Ashaig, near Broadford, is used by private aircraft and occasionally by NHS Highland and the Scottish Ambulance Service for transferring patients to hospitals on the mainland.[112]

The A87 trunk road traverses the island from the Skye Bridge to Uig, linking most of the major settlements. Many of the island's roads have been widened in the past forty years although there are still substantial sections of single track road.[5][18]

Culture, media, and the arts

Students of Scottish Gaelic travel from all over the world to attend Sabhal Mòr Ostaig, the Scottish Gaelic college based near Kilmore in Sleat.[113] In addition to members of the Church of Scotland and a smaller number of Roman Catholics, many residents of Skye belong to the Free Church of Scotland, known for its strict observance of the Sabbath.[Note 8]

Skye has a strong folk music tradition, although in recent years dance and rock music have been growing in popularity on the island. Gaelic folk rock band Runrig started in Skye and former singer Donnie Munro still works on the island.[115] Runrig's second single and a concert staple is entitled Skye, the lyrics being partly in English and partly in Gaelic[116] and they have released other songs such as "Nightfall on Marsco" that were inspired by the island.[117] Ex-Runrig member Blair Douglas, a highly regarded accordionist and composer in his own right, was born on the island and is still based there to this day. Celtic fusion band the Peatbog Faeries are based on Skye.[118] Jethro Tull singer Ian Anderson owned an estate at Strathaird on Skye at one time.[119] Several Tull songs are written about Skye, including Dun Ringil, Broadford Bazaar, and Acres Wild (which contains the lines "Come with me to the Winged Isle, / Northern father's western child..." in reference to the island itself).[120] The Isle of Skye Music Festival featured sets from The Fun Lovin' Criminals and Sparks, but collapsed in 2007.[121][122] Electronic musician Mylo was born on Skye.[123]

The poet Sorley MacLean, a native of the Isle of Raasay, which lies off the island's east coast, lived much of his life on Skye.[124] The island has been immortalised in the traditional song "The Skye Boat Song" and is the notional setting for the novel To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, although the Skye of the novel bears little relation to the real island.[125] John Buchan's descriptions of Skye, as featured in his Richard Hannay novel Mr Standfast, are more true to life.[126] I Diari di Rubha Hunis is a 2004 Italian language work of non-fiction by Davide Sapienza. The international bestseller, The Ice Twins, by S K Tremayne, published around the world in 2015–2016, is set in southern Skye, especially around the settlement and islands of Isleornsay.

Skye has been used as a location for a number of feature films. The Ashaig aerodrome was used for the opening scenes of the 1980 film Flash Gordon.[112] Stardust, released in 2007 and starring Robert De Niro and Michelle Pfeiffer, featured scenes near Uig, Loch Coruisk and the Quiraing.[128][129][130] Another 2007 film, Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle, was shot almost entirely in various locations on the island.[131] The Justin Kurzel adaption of Macbeth starring Michael Fassbender was also filmed on the Island.[132] Some of the opening scenes in Ridley Scott's 2012 feature film Prometheus were shot and set at the Old Man of Storr.[127] In 1973 The Highlands and Islands - a Royal Tour, a documentary about Prince Charles's visit to the Highlands and Islands, directed by Oscar Marzaroli, was shot partly on Skye.[133]

The West Highland Free Press is published at Broadford. This weekly newspaper takes as its motto An Tìr, an Cànan 's na Daoine ("The Land, the Language and the People"), which reflects its radical, campaigning priorities. The Free Press was founded in 1972 and circulates in Skye, Wester Ross and the Outer Hebrides.[134] Shinty is a popular sport played throughout the island and Portree-based Skye Camanachd won the Camanachd Cup in 1990.[135]

Wildlife

The Hebrides generally lack the biodiversity of mainland Britain,[136] but like most of the larger islands, Skye still has a wide variety of species. Observing the abundance of game birds Martin wrote:

There is plenty of land and water fowl in this isle—as hawks, eagles of two kinds (the one grey and of a larger size, the other much less and black, but more destructive to young cattle), black cock, heath-hen, plovers, pigeons, wild geese, ptarmigan, and cranes. Of this latter sort I have seen sixty on the shore in a flock together. The sea fowls are malls of all kinds—coulterneb, guillemot, sea cormorant, &c. The natives observe that the latter, if perfectly black, makes no good broth, nor is its flesh worth eating; but that a cormorant, which hath any white feathers or down, makes good broth, and the flesh of it is good food; and the broth is usually drunk by nurses to increase their milk.

— Martin Martin, A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland.[137]

Similarly, Samuel Johnson noted that:

At the tables where a stranger is received, neither plenty nor delicacy is wanting. A tract of land so thinly inhabited, must have much wild-fowl; and I scarcely remember to have seen a dinner without them. The moor-game is every where to be had. That the sea abounds with fish, needs not be told, for it supplies a great part of Europe. The Isle of Sky has stags and roebucks, but no hares. They sell very numerous droves of oxen yearly to England, and therefore cannot be supposed to want beef at home. Sheep and goats are in great numbers, and they have the common domestic fowls."

In the modern era avian life includes the corncrake, red-throated diver, kittiwake, tystie, Atlantic puffin, goldeneye and golden eagle. The eggs of the last breeding pair of white-tailed sea eagle in the UK were taken by an egg collector on Skye in 1916 but the species has recently been re-introduced.[138] The chough last bred on the island in 1900.[139][140] Mountain hare (apparently absent in the 18th century) and rabbit are now abundant and preyed upon by wild cat and pine marten.[141] The rich fresh water streams contain brown trout, Atlantic salmon and water shrew.[142][143] Offshore the edible crab and edible oyster are also found, the latter especially in the Sound of Scalpay.[144][145] There are nationally important horse mussel and brittlestar beds in the sea lochs[146] and in 2012 a bed of 100 million flame shells was found during a survey of Loch Alsh.[147] Grey Seals can be seen off the Southern coast.

Heather moor containing ling, bell heather, cross-leaved heath, bog myrtle and fescues is everywhere abundant. The high Black Cuillins weather too slowly to produce a soil that sustains a rich plant life, but each of the main peninsulas has an individual flora. The basalt underpinnings of Trotternish produce a diversity of Arctic and alpine plants including alpine pearlwort and mossy cyphal. The low-lying fields of Waternish contain corn marigold and corn spurry. The sea cliffs of Duirinish boast mountain avens and fir clubmoss. Minginish produces fairy flax, cats-ear and black bog rush.[148] There is a fine example of Brachypodium-rich ash woodland at Tokavaig in Sleat incorporating silver birch, hazel, bird cherry, and hawthorn.[149]

The local Biodiversity Action Plan recommends land management measures to control the spread of ragwort and bracken and identifies four non-native, invasive species as threatening native biodiversity: Japanese knotweed, rhododendron, New Zealand flatworm and mink. It also identifies problems of over-grazing resulting in the impoverishment of moorland and upland habitats and a loss of native woodland, caused by the large numbers of red deer and sheep.[150]

See also

- List of islands of Scotland

- Category:Mountains and hills of the Isle of Skye

- Timeline of prehistoric Scotland

Notes

- The largest of the Inner Hebrides that lie north of Skye are the Isle of Ewe, Tanera Mòr, and Handa, none of which exceed 310 hectares (770 acres) in size.[9] See also List of Inner Hebrides.

- English translation from Lowland Scots: "This isle is called Ellan Skiannach in Gaelic, that is to say in English, The Winged Isle, by reason of its many wings and points that come from it, through dividing of the land by the aforesaid lochs."[24]

- In April 2007 it was reported in the media that the island's official name had been changed by the Highland Council to Eilean a' Cheò. However, the Council clarified that this name referred only to one of its 22 wards in the forthcoming election, and that there were no plans to change signage or discontinue the English language name.[1][26]

- Skye's irregular shape is created by the 15 major sea lochs that penetrate so far into the mountainous core that no part of the island is more than 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from the sea.[1][10]

- Figures provided for Staffin, only a few miles to the east, average 4.6 °C (40.3 °F) in January and 15.6 °C (60.1 °F) in July at noon.[41]

- The theme of government neglect has been repeated by commentators spanning more than a century. "[The landlords] persuaded the Government for the second time to put the country to the expense of a naval expedition to Skye to exhibit Highlanders to the world as a race of men who could only be governed at the point of the bayonet, and that simply because the Commissioners had neglected to perform and pay for the duty the law imposed on them. (Cheers)." Sir Charles Cameron (1886).[85] "Nationalist MPs and crofters, frustrated by the failure of Westminster politicians to bring Scotland into line with England and other European nations by abolishing feudal structures and regulating land use, are drawing up plans to limit foreign land ownership and introduce environmental codes for all estates. They want ministers to compile a full public Land Register." John Arlidge (1996).[86]

- Carruthers was the editor of the National Illustrated Library's 1852 edition of Boswell (1785) who added a footnote to this effect.[87]

- The 2001 census statistics used are based on local authority areas and do not specifically identify Free Church adherents. However, the averages for Highland and Eilean Siar, between which the total for Skye is likely to lie are 48–42 per cent Church of Scotland, 7–13 per cent Roman Catholic and 12–28 per cent "Other Christian", of whom the majority will be Free Church members. The total for all other religions combined is 1 per cent for both areas.[114]

Citations

- Murray (1966) p. 146.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 173.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 502–03. Modified to include bridged islands.

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- "Get-a-map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 30 March 2008.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Infobox reference is Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 173–79 unless otherwise stated.

- "Isle of Skye". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 26 May 2019.

- "Rick Livingstone's Tables of the Islands of Scotland". (pdf) Region 8. North West, North & East coasts. Argyll Yacht Charters. Retrieved 12 December 2011.

- Slesser (1981) p. 19.

- Murray (1966) pp. 147–48.

- "Scotland's Island Populations". The Scottish Islands Federation. Retrieved 29 September 2007.

- "Gaelic Culture" Archived 22 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine. VisitScotland. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- "Portree, Raasay & Central Skye". A Guide. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- Murray (1966) p. 155.

- "Group 34: islands in the Irish Sea and the Western Isles 1". Kmatthews.org.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

- Strang, Alistair (1997) "Explaining Ptolemy's Roman Britain". Britannia. 28 pp. 1–30

- Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 173–79.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Ainmean-àite/Placenames. (pdf) Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 August 2012. p. 105.

- Gammeltoft, Peder (2007) p. 487.

- Jennings and Kruse (2009) pp. 79–80.

- "Haakon Haakonsøns Saga". Norwegian translation: P. A. Munch. Saganet.is. Retrieved 3 June 2008.

- "Magnus Barefoot's Saga". English translation: Wikisource. Retrieved 4 June 2008.

- Munro, D. (1818). Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2. Quoted in Murray (1966) p. 146.

- "Skye: A historical perspective". Gazetteer for Scotland. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- Tinning, William (1 May 2007) "Council says Isle of Skye will keep English name". Glasgow. The Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Martin, Martin (1703) "A Description of The Isle of Skye". p. 65.

- "Sgurr Dearg and the In Pinn". skyewalk.co.uk. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- Bennet (1986) p. 222.

- Wells, Colin (2007) "Running in Heaven". Glasgow. Sunday Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Johnstone et al. (1990) pp. 234–40.

- "The Kilt Rock, Skye". Earthwise. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Murray (1966) p. 149.

- Murray (1966) pp. 156–61.

- "The locality" Archived 15 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Elgol & Torrin Historical Society. (Comunn Eachdraidh Ealaghol agus Na Torran). Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- Murray (1966) pp. 147, 165.

- "Highland Profile" Archived 4 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine. The Highland Council (2011 estimate). Retrieved 26 December 2012

- "Magical places do exist...". Steininn.co.uk. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- McGoodwin (2001) p. 250.

- Cooper (1983) pp. 33–35. Averages for rainfall are for 1916–50, temperature 1931–60.

- Slesser (1981) pp. 31–33. (20-year averages). See also "Weather Data for Staffin Isle of Skye". Carbostweather.co.uk. Retrieved 7 June 2008.

- Murray (1966) p. 147.

- Slesser (1981) pp. 27–31.

- Murray (1973) p. 79.

- Valor, G. Ballester. "Synop report summary". www.ogimet.com.

- "Portree last 24 hours weather". Met Office.

- "Records and Averages". www.msn.com.

- Saville, Alan; Hardy, Karen; Miket, Roger; Ballin, Torben Bjarke "An Corran, Staffin, Skye: a Rockshelter with Mesolithic and Later Occupation" Archived 29 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Scottish Archaeology Internet Reports. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Wickham-Jones, C.R. and Hardy, K. "Scotlands First Settlers". History Scotland Magazine/Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Aesthetics, morality and bureaucracy: A case study of land reform and perceptions of landscape change in Northwest Scotland Archived 19 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf) Centre for International Environment and Development Studies. Noragric. Aas. Retrieved 19 May 2008.

- "Skye survey" Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- "Skye, Rubh' An Dunain, 'Viking Canal' ". Canmore. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- Coventry (2008) pp. 381–82.

- Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49.

- Jennings and Kruse (2009) p. 76.

- Jennings and Kruse (2009) p. 77.

- Sharpe (1995) Book I, chapter 26; Book II, chapter 33 & note 151.

- Fraser (2009) pp. 204–06, 249 & 252–53.

- Jennings and Kruse (2009) p. 87.

- "The Norse Connection" Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Celtictraditions.com. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- Mackinnon, C. R. (1958). "The Clan Mackinnon: a short history". Archived from the original on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Sellar (1999) pp. 3–4.

- "About the Clan MacInnes". Macinnes.org. Retrieved 8 December 2010.

- Murray (1966) p. 156.

- "Flora Macdonald's Grave, Kilmuir". Am Baile. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- Boswell (1785) pp. 142–43.

- Murray (1966) pp. 152–54.

- Hunter (2000) pp. 249–51.

- Johnson (1775) pp. 78–79.

- "Dunvegan Castle" Archived 2 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Dunvegancastle.com. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- "Armadale Castle". Clan Donald Centre. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- "The Barony of MacDonald". Baronage.co.uk Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- "Tusdale, Isle of Skye". Wild Country. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- "Skye, Tusdale". Canmore. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Cooper (1983) p. 77.

- "The collapse of the kelp industry" Archived 14 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Education Scotland. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- "The Skye and Raasay Clearances – 1853". Video from A history of Scotland: This Land is Our Land. BBC. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 176.

- "Battle of the Braes". Highlandclearances.info/Wayback Machine. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- "Suisnish, Skye". Canmore. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Allan, John "The Skye Guide". The Skye Guide. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Slesser (1981) p. 26.

- Hunter (2000) pp. 351–52.

- Cameron, Charles (1886). The Skye expedition of 1886 its constitutional and legal aspects. Speech delivered by Charles Cameron at a meeting held in the City Hall, Glasgow, on the 10th November, 1886. Glasgow. Alex. MacDonald.

- Arlidge, John (25 February 1996) "Who owns Scotland? Wealthy foreign owners of Scottish estates are facing a backlash from locals." London. The Independent. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- See Boswell (1785) p. 141 at Internet Archive. (pdf) Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901–2001 Gaelic in the Census. (PowerPoint) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 1 June 2008.

- "Member Profile: Charles Kennedy" Archived 18 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine. United Kingdom Parliament. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Local Government etc. (Scotland) Act 1994: Chapter 39". Archived 1 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "The Highland Council (Comhairle na Gaidhealtachd)". The Highland Council. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Ross, David (7 May 2011). "No Loyalty to LibDems in Highland Heartland". Election 2011 Supplement. Glasgow. The Herald.

- "The Aros Experience". Visit Scotland. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Wightman, Andy "Inverness". Who Owns Scotland. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- MacPhail, Issie (2002) Land, Crofting and The Assynt Crofters Trust: A Post-Colonial Geography?. University of Wales/Academia.edu. p. 174. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Welcome" page. Sleat Community Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- "Directory of Members" Archived 19 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Development Trusts Association Scotland. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

- Macpherson, George W. "Glendale Today". Caledonia.org.uk. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Talisker Scotch Whisky Distillery". Scotchwhisky.net. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Pràban – The Home of fine Scottish Whisky". Gaelicwhisky.com. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Sitekit reports a record year of growth" Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Pressport.co.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "The Croft House Kitchen" Archived 9 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Skye Museum of Island Life. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- Highland Biodiversity Project (2003) p. 7.

- "Welcome" Archived 31 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. Isle of Skye Renewables Cooperative Ltd. Retrieved 31 March 2008.

- Parker, David et al. (April 2008) "Leading by Example". Durham. New Sector. Issue 78.

- "Arts and Crafts" Archived 10 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Visit Scotland. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- HIE Skye and Wester Ross (2008) "About our area". Highlands and Islands Enterprise. Inverness. Statistics are not produced for Skye alone, but for the Skye and Wester Ross area, in which the public sector provides 37.1 per cent of the labour force.

- Alan Rehfisch (2007). "Ferry Services in Scotland" (pdf). SPICe Briefing. Scottish Parliament Information Centre. Retrieved 17 November 2007.

- "SKAT: The Drive for Justice". Skye and Kyle Against Tolls. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- "Getting Here". Isleofskye.net. Retrieved 24 October 2009.

- "Potential use of Skye's Ashaig airstrip re-examined". BBC News Online. (11 July 2012) Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "Welcome to Sabhal Mòr Ostaig" Archived 12 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. UHI Millennium Institute. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Pacione, Michael (2005) "The Geography of Religious Affiliation in Scotland". The Professional Geographer 57 (2) pp. 235–255. Oxford. Blackwell.

- "Donnie Munro: Biography" Archived 30 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Donniemunro.co.uk. Retrieved 5 April 2007

- "Skye" Archived 9 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Jimwillsher.co.uk. Retrieved 7 September 2009. The song also appears on the 1988 live Once in a Lifetime album.

- "Nightfall on Marsco" Archived 11 May 2010 at the Wayback MachineJimwillsher.co.uk. Retrieved 7 September 2009.

- "The Peatbog Faeries are ...". Peatbogfaeries.com. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Gough, Jim (30 May 2004). "Anderson swaps fish for his flute". Glasgow. Sunday Herald/Wayback Machine. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- The Annotated Jethro Tull Lyrics Page Archived 28 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Cupofwonder.com Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- Chiesa, Alison (28 April 2008) "Skye music festival pulled as administrators are called in". Glasgow. The Herald. Retrieved 28 December 2012.

- "Isle of Skye Music Festival 2006". Efestivals.co.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "Mylo – Biography". London. The Guardian. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- "Sorley Maclean 1911–1996". BBC. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- Westland (1997) p. 90.

- Mr Standfast Archived 24 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. John Buchan Society. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- "Prometheus Filming Location Round-up" Archived 14 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Prometheus News. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- "Stardust". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Stardust – The Quiraing". Scotland the Movie. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Stardust (2007)". Scotland the Movie. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- "Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle". Seachd.com Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- https://www.visitscotland.com/blog/films/michael-fassbender-filming-macbeth-isle-of-skye/

- "Full record for 'Highlands and Islands – a Royal Tour'". Scottish Screen Archive. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- West Highland Free Press. Broadford. Retrieved 2 March 2008.

- "Club History". Skye Camanachd. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- For example, there are only half the number of mammalian species that exist on mainland Britain. See Murray (1973) p. 72.

- Martin, Martin (1703). A Description of The Isle of Skye. p. 72.

- "The Demise of the White-Tailed Eagle in Scotland" Archived 23 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine. White-tailed-sea-eagle.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Fraser Darling (1969) p. 79.

- "Trotternish Wildlife" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Duntulm Castle. Retrieved 25 October 2009.

- Fraser Darling (1969) pp. 71–72.

- Fraser Darling (1969) p. 286.

- "Trout Fishing in Scotland: Skye". Trout-salmon-fishing.com. Retrieved 29 March 2008.

- Fraser Darling (1969) p. 84.

- "Native Oysters" Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. (pdf) (2005) Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 29 December 2012.

- Highland Biodiversity Project (2003) p. 6.

- "Marine Scotland survey uncovers 'huge' flame shell bed". BBC News Online. (27 December 2012) Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- Slack, Alf "Flora" in Slesser (1981) pp. 45–58.

- Fraser Darling (1969) p. 156.

- Highland Biodiversity Project (2003) pp. i, 3.

References

- Adomnán of Iona (1995). Sharpe, Richard (ed.). Life of St Columba. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-044462-9.

- Bennet, Donald (ed) (1986). The Munros. Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-13-4.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Boswell, James (1852) [1785]. Carruthers, Robert (ed.). The Journal of a Tour to the Hebrides. London: Office of the National Illustrated Library.

- Cooper, Derek (1983). Skye. Melbourne: Law Book Co of Australasia. ISBN 0-7100-9565-1.

- Coventry, Martin (2008). Castles of the Clans. Musselburgh: Goblinshead. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1.

- Fraser Darling, Frank; Boyd, J. Morton (1969). The Highlands and Islands. The New Naturalist. London: Collins. First published in 1947 under title: Natural history in the Highlands & Islands; by F. Fraser Darling.

- Fraser, James E. (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. The New Edinburgh History of Scotland. I. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1232-1.

- Gammeltoft, Peder "Scandinavian Naming-Systems in the Hebrides – A Way of Understanding how the Scandinavians were in Contact with Gaels and Picts?" in Ballin Smith, Beverley; Taylor, Simon; and Williams, Gareth (eds) (2007). West over Sea: Studies in Scandinavian Sea-Borne Expansion and Settlement Before 1300. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-15893-1.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Highland Biodiversity Project (2003). "Skye & Lochalsh Biodiversity Action Plan" (pdf). Convention on Biological Diversity. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Hunter, James (2000). Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1-84018-376-4.

- Jennings, Andrew and Kruse, Arne "One Coast – Three Peoples: Names and Ethnicity in the Scottish West during the Early Viking period" in Woolf, Alex (ed.) (2009). Scandinavian Scotland – Twenty Years After. St Andrews: St Andrews University Press. ISBN 978-0-9512573-7-1.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Johnson, Samuel (1924) [1775]. A Journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. London: Chapman & Dod.

- Johnstone, Scott; Brown, Hamish & Bennet, Donald (1990). The Corbetts and Other Scottish Hills. Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-29-0.

- McGoodwin, James R. (2001). Understanding the Cultures of Fishing Communities: A key to fisheries management and food security. Fisheries Technical Paper. 401. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization. ISBN 92-5-104606-9.

- Martin, Martin (1703). "A Description of The Western Islands of Scotland". Appin Regiment/Appin Historical Society. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2007. First printed for Andrew Bell and others, London.

- Murray, W. H. (1966). The Hebrides. London: Heinemann.

- Murray, W. H. (1973). The Islands of Western Scotland. London: Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0-413-30380-2.

- Sellar, William David Hamilton; Maclean, Alasdair (1999). The Highland clan MacNeacail (MacNicol): A History of the Nicolsons of Scorrybreac. Lochbay, Waternish: Maclean Press. ISBN 1-899272-02-X.

- Slesser, Malcolm (1981). The Island of Skye. Edinburgh: Scottish Mountaineering Trust. ISBN 0-907521-02-9.

- Westland, Ella (1997). Cornwall: the cultural construction of place. Penzance: Patten Press, in association with the Institute of Cornish Studies, University of Exeter. ISBN 1-872229-27-1.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Isle of Skye. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isle of Skye. |

- The official website for the Isle of Skye, Lochalsh and Raasay in the north west of Scotland

- Skye - Wikivoyage

- An historical perspective of Skye from the Ordnance Gazetteer of Scotland: A Survey of Scottish Topography, Statistical, Biographical and Historical, edited by Francis H. Groome. Originally published between 1882 and 1885 and provided on-line by the Gazetteer for Scotland.

- Skye photos

- Skye Flora

- Skye Birding Guide