Mountain hare

The mountain hare (Lepus timidus), also known as blue hare, tundra hare, variable hare, white hare, snow hare, alpine hare, and Irish hare, is a Palearctic hare that is largely adapted to polar and mountainous habitats.

| Mountain hare [1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| in its summer pelage | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Lagomorpha |

| Family: | Leporidae |

| Genus: | Lepus |

| Species: | L. timidus |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepus timidus | |

| |

| Mountain hare range (green - native, red - introduced) | |

Distribution

This species is distributed from Fennoscandia to eastern Siberia; in addition there are isolated mountain populations in the Alps, Scotland, the Baltics, northeastern Poland and Hokkaidō. In Ireland, the "Irish" hare (Lepus timidus hibernicus) does not grow a white winter coat, is smaller in size, and lives on lowland pastures, coastal grasslands and salt marshes, not just in the mountains. The mountain hare has also been introduced to Iceland, Shetland, Orkney, the Isle of Man, the Peak District, Svalbard, Kerguelen Islands, Crozet Islands, and the Faroe Islands.[3][4][5] In the Alps, the mountain hare lives at elevations from 700 to 3800 m, depending on biographic region and season.[6]

Description

The mountain hare is a large species, though it is slightly smaller than the European hare. It grows to a length of 45–65 cm (18–26 in), with a tail of 4–8 cm (1.6–3.1 in), and a mass of 2–5.3 kg (4.4–11.7 lb), females being slightly heavier than males. They can live for up to 12 years.[7][8] In summer, for all populations of mountain hares, the coat is various shades of brown. In preparation for winter most populations moult into a white (or largely white) pelage. The tail remains completely white all year round, distinguishing the mountain hare from the European hare (Lepus europaeus), which has a black upper side to the tail.[7] The subspecies Lepus timidus hibernicus (the Irish mountain hare) stays brown all year and individuals rarely develop a white coat. The Irish hare may also have a "golden" variation, particularly those found on Rathlin Island.

In the Faroe Islands, mountain hares turn gray in the winter instead of white. The winter-gray color may be caused by downregulation of the agouti hair cycle isoform in the autumn molt.[9]

Behaviour

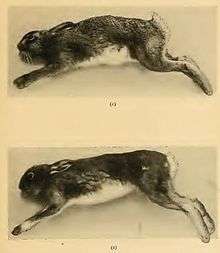

_Lepus_timidus.jpg)

Studies have shown that the diet of the mountain hare varies from region to region. It seems to be somewhat dependent on the particular habitat that the population under study lives in. For example, in northern Scandinavia where snow may blanket the ground for many months, the hares may graze on twigs and bark. In areas where snowfall is rare, such as Ireland, grass may form the bulk of the diet. Given a choice, mountain hares in Scotland and Ireland seem to prefer feeding on grasses. One study looking at mountain hares on a coastal grassland environment in Ireland found that grasses constituted over 90% of the diet. This was higher than the percentage of grass in the diet of the European rabbit (Oryctolagus cuniculus) that inhabited the same environment. The mountain hare is regionally the favourite prey of the golden eagle and may additionally be preyed on by Eurasian eagle-owls and red foxes. Stoats may prey on young hares.[8]

In northern parts of Finland, Norway and Sweden, the mountain hare and the European hare compete for habitat. The European hare, being larger, is usually able to drive away the mountain hare but is less adapted for living in snowy regions: its feet are smaller and its winter fur is a mixture of white and brown. While this winter fur is actually a very good camouflage in the coastal regions of Finland where the snow covers the shrubs but for a short time, the mountain hare is better adapted for the snowier conditions of the inland areas. The two may occasionally cross.

The Arctic hare (Lepus arcticus) was once considered a subspecies of the mountain hare, but it is now regarded as a separate species. Similarly, some scientists believe that the Irish hare should be regarded as a separate species. Fifteen subspecies are currently recognised.[2]

Human impact

In the European Alps the mountain hare lives at elevations from 700 to 3800 m, depending on biographic region and season. The development of alpine winter tourism has increased rapidly since the last few decades of the 20th century, resulting in expansion of ski resorts, growing visitor numbers, and a huge increase in all forms of snow sport activities. A 2013 study looking at stress events and the response of mountain hares to disturbance concluded that those hares living in areas of high winter recreational activities showed changes in physiology and behaviour that demanded additional energy input at a time when access to food resources is restricted by snow. It recommended ensuring that forests inhabited by mountain hares were kept free of tourist development, and that new skiing areas should be avoided in mountain hare habitat, and that existing sites should not be expanded.[10]

In August 2016, the Scottish animal welfare charity OneKind launched a campaign on behalf of the mountain hare, as a way of raising awareness of mountain hare culls taking place across the country and in garnering public support for the issue. Mountain hares are routinely shot in the Scottish Highlands both as part of paid hunting "tours" and by gamekeepers managing red grouse populations (who believe that mountain hares can be vectors of diseases which affect the birds). Much of this activity is secretive [11] but investigations have revealed that tens of thousands of hares are being culled every year.[12] The campaign, which urges people to proclaim that "We Care For The Mountain Hare", will culminate with the charity urging the Scottish government to legislate against commercial hunting and culling of the iconic Scottish species. The campaign has revealed widespread public support for a ban on hare hunting in Scotland. On May 17 2020, MSPs voted to ban the unlicensed culling of mountain hares and grant them protected species status within Scotland after a petition started by Green MSP Alison Johnstone gathered over 22,000 signatures.[13]

References

- Hoffman, R.S.; Smith, A.T. (2005). "Order Lagomorpha". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Smith, A.T.; Johnston, C.H. (2019). "Lepus timidus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T11791A45177198. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-1.RLTS.T11791A45177198.en.

- Long, John L. (2003). Introduced Mammals of the World: Their History, Distribution and Influence. Cabi Publishing (ISBN 9780851997483)

- www.divinefrog.co.uk, Divine Frog Web Services. "Hare Preservation Trust".

- "Mammals of the Faroes – Wild world - Nature, conservation and wildlife holidays". Retrieved 2019-04-25.

- Rehnus, M.: Der Schneehase in den Alpen. Ein Überlebenskünstler mit ungewisser Zukunft, Haupt Verlag, Bern 2013, ISBN 978-3-258-07846-5, p. 21

- "Mountain Hare". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2010-03-28. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- Macdonald, D.W.; Barrett , P. (1993). Mammals of Europe. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09160-0.

- "Introgression drives repeated evolution of winter coat color polymorphism in hares". doi:10.1073/pnas.1910471116. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Rehnus, M., Wehrle, M., Palme, R. (2013). "Mountain hares Lepus timidus and tourism: stress events and reactions." Journal of Applied Ecology 50(1):6-12. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1365-2664.12174/abstract

- https://theferret.scot/outrage-mass-killing-mountain-hares/ Outrage over mass killing of mountain hares, The Ferret, Rob Edwards, 14 March 2016

- https://theferret.scot/38000-mountain-hares-killed/ Nearly 38,000 mountain hares killed in one season, new data reveals, The Ferret, Billy Briggs, 18 May 2018

- "MSPs ban unlicensed culling of mountain hares". BBC News. Retrieved 18 June 2020.