Pan-Iranism

Pan-Iranism is an ideology that advocates solidarity and reunification of Iranian peoples living in the Iranian plateau and other regions that have significant Iranian cultural influence, including the Persians, Azeris,[2] Lurs, Gilaks, Mazanderanis, Kurds, Zazas, Talysh, Tajiks of Tajikistan and Afghanistan, Pashtuns, Ossetians, Baloch of Pakistan, etc. The first theoretician was Dr Mahmoud Afshar Yazdi.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

Origins and ideology

Iranian political scientist Dr. Mahmoud Afshar developed the Pan-Iranist ideology in the early 1920s in opposition to Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism, which were seen as potential threats to the territorial integrity of Iran.[9] He also displayed a strong belief in the nationalist character of Iranian people throughout the country’s long history.[9]

Unlike similar movements of the time in other countries, Pan-Iranism was ethnically and linguistically inclusive and solely concerned with territorial nationalism, rather than ethnic or racial nationalism.[10] On the eve of World War I, pan-Turkists focused on the Turkic-speaking lands of Iran, Caucasus and Central Asia.[11] The ultimate purpose was to persuade these populations to secede from the larger political entities to which they belonged and join the new pan-Turkic homeland.[11] It was the latter appeal to Iranian Azerbaijanis, which, contrary to Pan-Turkist intentions, caused a small group of Azerbaijani intellectuals to become the strongest advocates of the territorial integrity of Iran.[11] After the constitutional revolution in Iran, a romantic nationalism was adopted by Azerbaijani Democrats as a reaction to the pan-Turkist irredentist policies threatening Iran’s territorial integrity.[11] It was during this period that Iranism and linguistic homogenization policies were proposed as a defensive nature against all others.[11] Contrary to what one might expect, foremost among innovating this defensive nationalism were Iranian Azerbaijanis.[11] They viewed that assuring the territorial integrity of the country was the first step in building a society based on law and a modern state.[11] Through this framework, their political loyalty outweighed their ethnic and regional affiliations.[11] The adoption of these integrationist policies paved the way for the emergence of the titular ethnic group’s cultural nationalism.[11]

History

With the collapse of the Qajar dynasty, which had descended into corruption, and the rise of Reza Shah Pahlavi in 1925, who began introducing secular reforms limiting the power of the Shia clergy, Iranian nationalist and socialist thinkers had hoped that this new era would also witness the introduction of democratic reforms. However, such reforms did not take place. This culminated in the gradual rise of a loosely organized grass roots Pan-Iranist movement made up of nationalist writers, teachers, students, and activists allied with other pro-democracy movements.

In the 1940s, following the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran, the Pan-Iranist movement gained momentum and popularity as a result of the widespread feeling of insecurity among Iranians who saw the king, Reza Shah, powerless against such foreign presence in the country. There were soldiers from Russia, England, India, New Zealand, Australia and later on, America, present in the country, especially in the capital, Tehran.[12] The Allied occupation influenced a series of student movements in 1941. One of these new groups was an underground nationalist guerrilla group called the Revenge group, also known as the Anjoman.[12] The Pan-Iranist Party was founded later on by two of the members of the Revenge group and two other students in the mid-to-late 1940s in Tehran University. Though the pan-Iranist movement had been active throughout the 1930s, it had been a loosely organized grass roots alliance of nationalist writers, teachers, students, and activists. The party was the first organization to officially adopt the pan-Iranist position, which believed in the solidarity and reunification of the Iranian peoples inhabiting the Iranian plateau. In 1951, the party leaders Mohsen Pezeshkpour and Dariush Forouhar came to a disagreement as to how the party should operate, and a division occurred. The two factions greatly differed in their organizational structure and practice. The Pezeskpour faction, which retained the party name, believed in working within the system of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Forouhar faction, which adopted a new name, Mellat Iran (Nation of Iran Party), believed in working against the system.[12]

Iran-e-Bozorg

Iran-e Bozorg was a periodical published in the city of Rasht by the Armenian political activist Gregory Yeghikian (Armenian: Գրիգոր Եղիկյան). It advocated the unification of Iranian peoples (e.g., Afghans, Kurds, etc.) included the Armenians. Yaqikiān believed that, with education and the rising of the levels of people’s awareness, such a goal was feasible through peaceful means. The journal benefited from the contributions of a number of leading intellectuals of the time, including Moḥammad Moʿin and ʿAli Esfandiāri (Nimā Yušij), and carried articles, poetry, a serialized story, and some news. It also published articles in support of the Kurds who had risen in rebellion in Turkey, which caused the protest of the Turkish counsel in Rasht and led to the banning of the paper by the order of the minister of court. Yaqikiān tried, without success, to have the ban removed and eventually moved to Tehran, where he published the paper Irān-e Konuni.[13]

See also

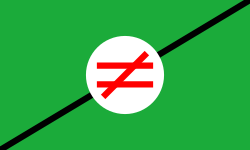

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan-Iranian flags. |

Further reading

- Hezbe Pan Iranist by Ali Kabar Razmjoo (ISBN 964-6196-51-9)

- Engheta, Naser (2001). 50 years history with the Pan-Iranists. Los Angeles, CA: Ketab Corp. ISBN 1-883819-56-3.

References

- "Iran i. Lands of Iran". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- Farjadian, S.; Ghaderi, A. (December 2007). "HLA class II similarities in Iranian Kurds and Azeris". International Journal of Immunogenetics. 34 (6): 457–463. doi:10.1111/j.1744-313x.2007.00723.x. ISSN 1744-3121. PMID 18001303.

Neighbor‐joining tree based on Nei's genetic distances and correspondence analysis according to DRB1, DQA1 and DQB1 allele frequencies showed a strong genetic tie between Kurds and Azeris of Iran. The results of AMOVA revealed no significant difference between these populations and other major ethnic groups of Iran

- Professor Richard Frye states:The Turkish speakers of Azerbaijan are mainly descended from the earlier Iranian speakers, several pockets of whom still exist in the region (Frye, Richard Nelson, “Peoples of Iran”, in Encyclopedia Iranica).

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz. “Azerbaijan, Republic of”,., Vol. 3, Colliers Encyclopedia CD-ROM, 02-28-1996: “The original Persian population became fused with the Turks, and gradually the Persian language was supplanted by a Turkic dialect that evolved into the distinct Azerbaijani language.”

- Golden, P.B. “An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples”, Otto Harrosowitz, 1992. “The Azeris of today are an overwhelmingly sedentary, detribalized people. Anthropologically, they are little distinguished from the Iranian neighbo”

- Xavier Planhol, “Lands of Iran” in Encyclopedia Iranica. Excerpt: The toponyms, with more than half of the place names of Iranian origin in some areas, such as the Sahand, a huge volcanic massif south of Tabriz, or the Qara Dagh, near the border (Planhol, 1966, p. 305; Bazin, 1982, p. 28) bears witness to this continuity. The language itself provides eloquent proof. Azeri, not unlike Uzbek (see above), lost the vocal harmony typical of Turkish languages. It is a Turkish language learned and spoken by Iranian peasants.”(Encyclopedia Iranica, “Lands of Iran”)

- “Thus Turkish nomads, in spite of their deep penetration throughout Iranian lands, only slightly influenced the local culture. Elements borrowed by the Iranians from their invaders were negligible.”(X.D. Planhol, Lands of Iran in Encyclopedia Iranica)

- История Востока. В 6 т. Т. 2. Восток в средние века. Глава V. — М.: «Восточная литература», 2002. — ISBN 5-02-017711-3 . Excerpt: ""Говоря о возникновении азербайджанской культуры именно в XIV-XV вв., следует иметь в виду прежде всего литературу и другие части культуры, органически связанные с языком. Что касается материальной культуры, то она оставалась традиционной и после тюркизации местного населения. Впрочем, наличие мощного пласта иранцев, принявших участие в формировании азербайджанского этноса, наложило свой отпечаток прежде всего на лексику азербайджанского языка, в котором огромное число иранских и арабских слов. Последние вошли и в азербайджанский, и в турецкий язык главным образом через иранское посредство. Став самостоятельной, азербайджанская культура сохранила тесные связи с иранской и арабской. Они скреплялись и общей религией, и общими культурно-историческими традициями." (History of the East. 6 v. 2. East during the Middle Ages. Chapter V. - M.: «Eastern literature», 2002. - ISBN 5-02-017711-3.). Translation:"However, the availability of powerful layer of Iranians took part in the formation of the Azerbaijani ethnic group, left their mark primarily in the Azerbaijani language, in which a great number of Iranian and Arabic words. The latter included in the Azeri, and Turkish language primarily through Iranian mediation."

- AHMAD ASHRAF, "IRANIAN IDENTITY IN THE 19TH AND 20TH CENTURIES", Encyclopedia Iranica. Also accessible here:. Excerpt: "Afšār, a political scientist, pioneered systematic scholarly treatment of various aspects of Iranian national identity, territorial integrity, and national unity. An influential nationalist, he also displayed a strong belief in the nationalist character of Iranian people throughout the country’s long history. He was the first to propose the idea of Pan-Iranism to safeguard the unity and territorial integrity of the nation against the onslaught of Pan-Turkism and Pan-Arabism (Afšār, p. 187)"

- Perspectives on Iranian identity, pg.26 Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- Touraj Atabaki, “Recasting Oneself, Rejecting the Other: Pan-Turkism and Iranian Nationalism” in Van Schendel, Willem(Editor). Identity Politics in Central Asia and the Muslim World: Nationalism, Ethnicity and Labour in the Twentieth Century. London, GBR: I. B. Tauris & Company, Limited, 2001. Actual Quote:

As far as Iran is concerned, it is widely argued that Iranian nationalism was born as a state ideology in the Reza Shah era, based on philological nationalism and as a result of his innovative success in creating a modern nation-state in Iran. However, what is often neglected is that Iranian nationalism has its roots in the political upheavals of the nineteenth century and the disintegration immediately following the Constitutional revolution of 1905– 9. It was during this period that Iranism gradually took shape as a defensive discourse for constructing a bounded territorial entity – the ‘pure Iran’ standing against all others. Consequently, over time there emerged among the country’s intelligentsia a political xenophobia which contributed to the formation of Iranian defensive nationalism. It is noteworthy that, contrary to what one might expect, many of the leading agents of the construction of an Iranian bounded territorial entity came from non Persian-speaking ethnic minorities, and the foremost were the Azerbaijanis, rather than the nation’s titular ethnic group, the Persians. .... In the middle of April 1918, the Ottoman army invaded Azerbaijan for the second time. ... Contrary to their expectations, however, the Ottomans did not achieve impressive success in Azerbaijan. Although the province remained under quasi-occupation by Ottoman troops for months, attempting to win endorsement for pan-Turkism ended in failure. ... The most important political development affecting the Middle East at the beginning of the twentieth century was the collapse of the Ottoman and the Russian empires. The idea of a greater homeland for all Turks was propagated by pan-Turkism, which was adopted almost at once as a main ideological pillar by the Committee of Union and Progress and somewhat later by other political caucuses in what remained of the Ottoman Empire. On the eve of World War I, pan-Turkist propaganda focused chiefly on the Turkic-speaking peoples of the southern Caucasus, in Iranian Azerbaijan and Turkistan in Central Asia, with the ultimate purpose of persuading them all to secede from the larger political entities to which they belonged and to join the new pan-Turkic homeland. It was this latter appeal to Iranian Azerbaijanis which, contrary to pan-Turkist intentions, caused a small group of Azerbaijani intellectuals to become the most vociferous advocates of Iran’s territorial integrity and sovereignty. If in Europe ‘romantic nationalism responded to the damage likely to be caused by modernism by providing a new and larger sense of belonging, an all-encompassing totality, which brought about new social ties, identity and meaning, and a new sense of history from one’s origin on to an illustrious future’,(42) in Iran after the Constitutional movement romantic nationalism was adopted by the Azerbaijani Democrats as a reaction to the irredentist policies threatening the country’s territorial integrity. In their view, assuring territorial integrity was a necessary first step on the road to establishing the rule of law in society and a competent modern state which would safeguard collective as well as individual rights. It was within this context that their political loyalty outweighed their other ethnic or regional affinities. The failure of the Democrats in the arena of Iranian politics after the Constitutional movement and the start of modern state-building paved the way for the emergence of the titular ethnic group’s cultural nationalism. Whereas the adoption of integrationist policies preserved Iran’s geographic integrity and provided the majority of Iranians with a secure and firm national identity, the blatant ignoring of other demands of the Constitutional movement, such as the call for formation of society based on law and order, left the country still searching for a political identity.

- Engheta, Naser (2001). 50 years history with the Pan-Iranists. Los Angeles, CA: Ketab Corp. ISBN 978-1-883819-56-9.

- "IRAN-E KABIR – Encyclopaedia Iranica". Iranicaonline.org.