Pan-Iranist Party

The Pan-Iranist Party (Persian: حزب پانایرانیست, romanized: Ḥezb-e Pān-Irānist) is a small[5] opposition political party in Iran that advocates pan-Iranism. The party is not registered and is technically banned, however it continues to operate inside Iran.[1]

Pan-Iranist Party | |

|---|---|

| General Secretary | Zahra Gholamipour[1] |

| Spokesperson | Manouchehr Yazdi |

| Head of Youth Wing | Hojjat Kalashi |

| Founder | Mohsen Pezeshkpour and Dariush Forouhar[2] |

| Founded | 1941[3] |

| Headquarters | Tehran, Iran |

| Parliamentary wing | Pan-Iranist parliamentary group (1967–71; 1978–79) |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Far-right[7] |

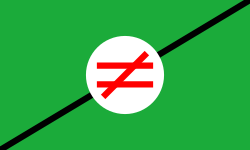

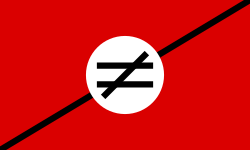

| Colors | Green, White, Red (Iranian Tricolore) Grey (customary) |

| Parliament | 0 / 290

|

| Election symbol | |

| ≠ | |

| Party flag | |

| |

| Website | |

| paniranist-party | |

| |

During the Pahlavi dynasty, the party was represented in the Parliament[8] and considered a semi-opposition within the regime, allowed to operate until officially denouncing Iran's assent to Bahraini independence in 1971.[9] The party was forced to close down and merge into the Resurgence Party in 1975.

It is an occasional supporter of the major nationalist party, National Front, and was nationalist and fascist with respect to its ideology.[10] Pan-Iranist Party was an anti-communist organization and regularly battled Tudeh Party of Iran mobs in the streets of Tehran.[11]

Pan-Iranist Party spoke supportive of the Iranian Green Movement in 2009[12] and its discourse was revived in the 2010s by the conservatives who tactically adopted its positions amidst Iran–Saudi disagreements and clash.[13]

Background

The invasion of Iran by Anglo-Soviet armies in the early 20th century led to a sense of insecurity among Iranians who saw the king, Reza Shah, powerless against such foreign presence in the country. There were soldiers from Russia, England, India, New Zealand, Australia and later on, America, present in the country, especially in the capital, Tehran.[14]

The Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran influenced a series of student movements in 1941 where nationalism was gaining popularity more than ever between Iranians, one of these new groups was an underground nationalist guerrilla group called the Revenge group (also known as the Anjoman).[14]

The Pan-Iranist Party was founded later on by two of the members of the revenge group and two other students in the mid-to-late 1940s in Tehran University. Though the pan-Iranist movement had been active throughout the 1930s, it had been a loosely organized grass roots alliance of nationalist writers, teachers, students, and activists. The party was the first organization to officially adopt the pan-Iranist position, which believed in the solidarity and reunification of the Iranian peoples inhabiting the Iranian plateau.

History

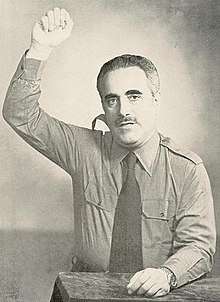

In 1951, Mohsen Pezeshkpour and Dariush Forouhar came to a disagreement as to how the party should operate, and a division occurred. The Pezeskpour faction, which retained the party name, believed in working within the system of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. The Forouhar faction, which adopted a new name, Mellat Iran (Nation of Iran Party), believed in working against the system. Mellat Iran was far more fervently nationalist than the former party, and strongly supported and was allied with the national movement of Mohammad Mossadegh, who had founded the National Front of Iran (Jebhe Melli) with other Iranian nationalist leaders.

The party was allegedly funded by the Central Intelligence Agency through TPBEDAMN.[15]

After the British-American sponsored coup d'etat against Mossadegh, the Shah assumed dictatorial powers and outlawed almost all political groups, including Mellat Iran and the National Front. The Pan-Iranist Party soon became the official opposition in the Majlis, with Pezeshkpour as Speaker. However, in reality, the party had very little political power and influence and its position was primarily intended to be symbolic. Beginning in the late 1960s, under the government of Amir Abbas Hoveyda, Iran mostly became a one-party dictatorship under the Imperial Resurrection Party (Rastakhiz).

Pezeshkpour remained active in the Majlis and spoke out against British rule in Bahrain, which Iran claimed. He established a residence in the city of Khorramshahr, which at the time was home to some of the most exclusive neighborhoods in Iran, and which also became his base of operations. In Khuzestan the party was for the first time able to become a dominant influence, whereas in the rest of Iran, the party continued to have very little effect.

With the onset of revolution in 1978, Pezeshkpour and other politicians who had been allied with the Shah fled the country into exile. Mohammad Reza Ameli Tehrani, a co-founder of the party, was sentenced to death by the Revolutionary Court, and subsequently executed in May 1979. Nationalist movements such as Mellat Iran and the National Front, which had been opposed to the Shah, remained in the country and played a crucial role in the revolutionary provisional government of Mehdi Bazargan. After the Islamic Revolution of 1979 which eventually saw the rise to power of Khomeini to the position of Supreme Leader after the collapse of the provisional government, all nationalist groups, as well as socialist and communist movements such as the Tudeh Party, were banned.

In the early 1990s, Pezeshkpour wrote a letter of apology to the new Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, stating that he wished to return to Iran and promised to stay out of politics for good. Khamenei accepted the apology and allowed Pezeshkpour to return, on the condition that he not resume his previous political activities. However, sometime afterwards Pezeshkpour became active in politics once again and reestablished the Pan-Iranist Party in Iran. He reformed the party structure and abandoned much of the old organizational ideology which Forouhar had opposed and which had originally led to the division. However, the Pan-Iranist Party and Mellat Iran did not reconcile and continued to function as separate organizations.

In the wake of the student demonstrations of 1999, many members of the Pan-Iranist Party were arrested[16] and nine members of the party leadership, including Pezeshkpour himself, were summoned to the Islamic Revolutionary Court. The charges made against them included distribution of anti-government propaganda in the official party newspaper, National Sovereignty.

In the summer of 2004, an attempt by a motorist, allegedly an undercover operative of the Ministry of Intelligence, on the life of Mohsen Pezeshkpour failed in front of his residence in Tehran.

On August 27, 2009, Hossein Shahriari, Reza Kermani, and Hojat Kalashi, three veteran members of the Pan Iranist Party, were arrested in the residence of Reza Kermani and sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for “propaganda against the regime, and being a member of the Pan Iranist Party” by the Revolutionary Court in Karaj.[17]

During January, 2011, co-founder of the Pan Iranist Party, Mohsen Pezeshkpour was announced dead when under house arrest by the Iranian Government. As a result, Reza Kermani was declared the new leader of the Pan Iranist Party.

Sometime in 2012, Reza Kermani died due to health issues brought upon him by the 18 months imprisonment within Rajaiee Shahr Prison, where conditions have been deemed inhumane by many and criticised internationally.

Organization

The differences between Forouhar and Pezeshkpour lay mostly in organizational structure and policy, though there were specific ideological differences as well. Forouhar strongly believed in democracy and cooperation with other Iranian parties, including leftist-oriented groups, whereas Pezeshkpour believed in a more authoritarian approach and opposed alliances with non-nationalist organizations. However, alliances with other nationalist groups were rare or non-existent as most were officially banned (such as Mellat Iran). Under Pezeshkpour, the Pan-Iranist Party also took on a decidedly paramilitary structure, with members being assigned military ranks and titles. All active members, both male and female, wore uniforms to party functions. Forouhar also strongly opposed this, though this paramilitary nature was largely symbolic, and party members did not actually carry weapons. Ordinary members were not required to wear uniforms. Beginning in the late 1960s, Pezeshkpour also had several personal bodyguards who were assigned to protect him at all times.

The symbol of the party was a crossed out equal sign (=), signifying inequality. This was in reference to foreign powers such as Britain and the Soviet Union, and symbolized the Pan-Iranist view that Iran must uphold its national sovereignty and interests above all else. The philosophical meaning attributed to this symbol according to the party's literature was that, in reality, there is no equality amongst nations, and that each nation must struggle to rise above all others, otherwise risking oblivion. This symbolism and philosophy also played a crucial role in the division between Forouhar and Pezeshkpour.

Pezeshkpour was often criticized by other nationalists for having not supported Mossadegh, and for his role in the Shah's government as Speaker of Majlis, as this position had no real power. Nationalist leaders viewed the failure of his opposition to the separation of Bahrain as evidence that his function was strictly symbolic.

When Pezeshkpour set about restoring the party after returning to Iran, he and other former party leaders renounced the former paramilitary structure of the organization as well as its authoritarianism, instead proclaiming their commitment to plurality and democracy, as well as a willingness to cooperate with other opposition groups. They continue to maintain the original party symbolism.

Election results

| Year | Election | Party leader | Seats won |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | Parliamentary | Mohsen Pezeshkpour | 5 / 219 (2%) |

| 1968 | Local | Mohsen Pezeshkpour | 20 / 1,068 (2%) |

References

- "COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION REPORT: IRAN" (PDF). Independent Advisory Group on Country. 31 August 2010. pp. 230, 234.

- Abrahamian, Ervand (1982). Iran Between Two Revolutions. Princeton University Press. pp. 257–258. ISBN 978-0-691-10134-7.

- Rubin, Michael (2001). Into the Shadows: Radical Vigilantes in Khatami's Iran. Washington Institute for Near East Policy. p. 90. ISBN 978-0944029459.

- Azimi, Fakhreddin (2008). Quest for Democracy in Iran: A Century of Struggle Against Authoritarian Rule. Harvard University Press. p. 253. ISBN 978-0674027787.

- Weinbaum, Marvin (1973), "Iran finds a party system: the institutionalization of Iran Novin", The Middle East Journal, 27 (4): 439–455, JSTOR 4325140

- Chubin, Shahram; Zabih, Sepehr (1974). The Foreign Relations of Iran: A Developing State in a Zone of Great-power Conflict. University of California Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-0520026834.

- The Middle East and North Africa 2003. Psychology Press. 2002. p. 416. ISBN 978-1857431322.

- Milani, Abbas (2000). The Persian Sphinx: Amir Abbas Hoveyda and the Riddle of the Iranian Revolution. I.B.Tauris. p. 381. ISBN 9781850433286.

Several reports from the American Embassy in Tehran refer to the Pan Iranist Party as one whose leadership was controlled by the government. For example, one report indicated that "Pan lranist deputies elected ... to Majlis can be expected to serve primarily as a propaganda instrument." National Archive, "Confidential Airgram: Pan Iranist Party, August 30, 1967." In another dispatch called "the Noisy Pan Iranists in Parliament" the embassy reports that "it should be emphasized that for many of these men-particularly the older ones- membership in the party has brought tangible rewards. Largely because of its close SAVAK connections, the party has been able to advance the careers of its members." NA, "The Noisy Pan Iranists in the Parliament, January 27, 1968."

- Houchang E. Chehabi (1990). Iranian Politics and Religious Modernism: The Liberation Movement of Iran Under the Shah and Khomeini. I.B.Tauris. pp. 211, 272. ISBN 978-1850431985.

- Poulson, Stephen (2006). Social Movements in Twentieth-century Iran: Culture, Ideology, and Mobilizing Frameworks. Lexington Books. p. 147. ISBN 978-0739117576.

- Mark J. Gasiorowski (1987). "Disintegration of Iranian National Front: Causes and Motives". The 1953 Coup d'Etat in Iran. Cambridge University Press. 19 (3): 261–286. doi:10.1017/s0020743800056737.

- Golnaz Esfandiari (22 June 2009). "Women At Forefront Of Iranian Protests". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Nozhan Etezadosaltaneh (4 August 2016). "Pan-Iranism: New Tactics of Conservatives in Iran". International Policy Digest. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Engheta, Naser (2001). 50 years history with the Pan-Iranists. Los Angeles, CA: Ketab Corp. ISBN 978-1-883819-56-9.

- Rahnema, Ali (2014-11-24). Behind the 1953 Coup in Iran: Thugs, Turncoats, Soldiers, and Spooks. Cambridge University Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-1107076068.

- "RFE/RL Iran Report".

- "Hossein Shahriari on Temporary Leave | the official website of the Pan Iranist party".