Indian Space Research Organisation

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO, /ˈɪsroʊ/) (Hindi; IAST: bhārtīya antrikṣ anusandhān saṅgṭhan) is the space agency of the Government of India and has its headquarters in the city of Bangalore (also known as Bengaluru). Its vision is to "harness space technology for national development while pursuing space science research & planetary exploration".[6] The Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) was established by Jawaharlal Nehru[7][8][9][10][11] under the Department of Atomic Energy (DAE) in 1962, with the urging of scientist Vikram Sarabhai recognising the need in space research. INCOSPAR grew and became ISRO in 1969,[12] also under the DAE.[13][14] In 1972, the Government of India had set up a Space Commission and the Department of Space (DOS),[15] bringing ISRO under the DOS. The establishment of ISRO thus institutionalised space research activities in India.[16] It is managed by the DOS, which reports to the Prime Minister of India.[17]

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | ISRO |

| Formed | 15 August 1969 |

| Preceding agency | |

| Type | Space agency |

| Headquarters | Bangalore, Karnataka, India 12°57′56″N 77°41′53″E |

| K. Sivan[3] | |

| Chairman | K. Sivan (ex-officio)[3] |

| Primary spaceports |

|

| Owner | Department of Space |

| Employees | 17,222 as of 2020[4] |

| Annual budget | (Ranked 7th) |

| Website | www |

ISRO built India's first satellite, Aryabhata, which was launched by the Soviet Union on 19 April 1975.[18] It was named after the mathematician Aryabhata. In 1980, Rohini became the first satellite to be placed in orbit by an Indian-made launch vehicle, SLV-3. ISRO subsequently developed two other rockets: the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) for launching satellites into polar orbits and the Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) for placing satellites into geostationary orbits. These rockets have launched numerous communications satellites and Earth observation satellites. Satellite navigation systems like GAGAN and IRNSS have been deployed. In January 2014, ISRO used an indigenous cryogenic engine CE-7.5 in a GSLV-D5 launch of the GSAT-14.[19][20]

ISRO sent a lunar orbiter, Chandrayaan-1, on 22 October 2008, which discovered lunar water in the form of ice,[21] and the Mars Orbiter Mission, on 5 November 2013, which entered Mars orbit on 24 September 2014, making India the first nation to succeed on its maiden attempt to Mars, as well as the first space agency in Asia to reach Mars orbit.[22] On 18 June 2016, ISRO launched twenty satellites in a single vehicle,[23] and on 15 February 2017, ISRO launched one hundred and four satellites in a single rocket (PSLV-C37), a world record.[24][25] ISRO launched its heaviest rocket, Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle-Mark III (GSLV-Mk III), on 5 June 2017 and placed a communications satellite GSAT-19 in orbit. With this launch, ISRO became capable of launching 4-ton heavy satellites into GTO. On 22 July 2019, ISRO launched its second lunar mission Chandrayaan-2 to study the lunar geology and the distribution of lunar water.

Future plans include development of the Unified Launch Vehicle, Small Satellite Launch Vehicle, development of a reusable launch vehicle, human spaceflight, a space station, interplanetary probes, and a solar spacecraft mission.[26]

Formative years

Modern space research in India is traced to the 1920s, when scientist S. K. Mitra conducted a series of experiments leading to the sounding of the ionosphere by applying ground-based radio methods in Kolkata.[28] Later, Indian scientists like C.V. Raman and Meghnad Saha contributed to scientific principles applicable in space sciences.[28] However, it was the period after 1945 that saw important developments being made in coordinated space research in India.[28] Organised space research in India was spearheaded by two scientists: Vikram Sarabhai—founder of the Physical Research Laboratory at Ahmedabad—and Homi Bhabha, who established the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in 1945.[28] Engineers were drawn from the Indian Ordnance Factories on deputation to harness their knowledge of propellants and advanced metallurgy as the Ordnance factories were the only organisation specialising in these technologies at that time. Initial experiments in space sciences included the study of cosmic radiation, high altitude and airborne testing, deep underground experimentation at the Kolar mines—one of the deepest mining sites in the world—and studies of the upper atmosphere.[29] Studies were carried out at research laboratories, universities, and independent locations.[29][30]

In 1950, the Department of Atomic Energy was founded with Bhabha as its secretary.[30] The department provided funding for space research throughout India.[31] During this time, tests continued on aspects of meteorology and the Earth's magnetic field, a topic that was being studied in India since the establishment of the observatory at Colaba in 1823. In 1954, the Uttar Pradesh state observatory was established at the foothills of the Himalayas.[30] The Rangpur Observatory was set up in 1957 at Osmania University, Hyderabad. Space research was further encouraged by the government of India.[31] In 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik 1 and opened up possibilities for the rest of the world to conduct a space launch.[31]

The Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR) was set up in 1962.[7]

Goals and objectives

The prime objective of ISRO is to use space technology and its application to various national tasks.[32] The Indian space programme was driven by the vision of Vikram Sarabhai, considered the father of the Indian space programme.[33][34] As he said in 1969:

There are some who question the relevance of space activities in a developing nation. To us, there is no ambiguity of purpose. We do not have the fantasy of competing with the economically advanced nations in the exploration of the Moon or the planets or manned space-flight. But we are convinced that if we are to play a meaningful role nationally, and in the community of nations, we must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to the real problems of man and society, which we find in our country. And we should note that the application of sophisticated technologies and methods of analysis to our problems is not to be confused with embarking on grandiose schemes, whose primary impact is for show rather than for progress measured in hard economic and social terms.

Former president of India, A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, said:

Very many individuals with myopic vision questioned the relevance of space activities in a newly independent nation which was finding it difficult to feed its population. But neither Prime Minister Nehru nor Prof. Sarabhai had any ambiguity of purpose. Their vision was very clear: if Indians were to play a meaningful role in the community of nations, they must be second to none in the application of advanced technologies to their real-life problems. They had no intention of using it merely as a means of displaying our might.

India's economic progress has made its space program more visible and active as the country aims for greater self-reliance in space technology.[37] In 2008, India launched as many as eleven satellites, including nine foreign and went on to become the first nation to launch ten satellites on one rocket.[37] ISRO has put into operation two major satellite systems: the Indian National Satellites (INSAT) for communication services, and the Indian Remote Sensing Programme (IRS) satellites for management of natural resources.

In July 2012, Abdul Kalam said that research was being done by ISRO and DRDO for developing cost-reduction technologies for access to space.[38]

Organisation structure and facilities

_-_organization_chart.svg.png)

ISRO is managed by the Department of Space (DoS) of the Government of India. DoS itself falls under the authority of the Space Commission and manages the following agencies and institutes:[39][40][41]

- Indian Space Research Organisation

- Antrix Corporation – The marketing arm of ISRO, Bangalore.

- Physical Research Laboratory (PRL), Ahmedabad.

- National Atmospheric Research Laboratory (NARL), Gadanki, Andhra pradesh.

- New Space India Limited - Commercial wing, Bangalore.

- North-Eastern Space Applications Centre[42] (NE-SAC), Umiam.

- Semi-Conductor Laboratory (SCL), Mohali.

- Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST), Thiruvananthapuram – India's space university.

Research facilities

| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Vikram Sarabhai Space Centre | Thiruvananthapuram | The largest ISRO base is also the main technical centre and the venue of development of the SLV-3, ASLV, and PSLV series.[43] The base supports India's Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station and the Rohini Sounding Rocket programme.[43] This facility is also developing the GSLV series.[43] |

| Liquid Propulsion Systems Centre | Thiruvananthapuram and Bangalore | The LPSC handles design, development, testing and implementation of liquid propulsion control packages, liquid stages and liquid engines for launch vehicles and satellites.[43] The testing of these systems is largely conducted at IPRC at Mahendragiri.[43] The LPSC, Bangalore also produces precision transducers.[44] |

| Physical Research Laboratory | Ahmedabad | Solar planetary physics, infrared astronomy, geo-cosmo physics, plasma physics, astrophysics, archaeology, and hydrology are some of the branches of study at this institute.[43] An observatory at Udaipur also falls under the control of this institution.[43] |

| Semi-Conductor Laboratory | Chandigarh | Research & Development in the field of semiconductor technology, micro-electro mechanical systems and process technologies relating to semiconductor processing. |

| National Atmospheric Research Laboratory | Tirupati | The NARL carries out fundamental and applied research in atmospheric and space sciences. |

| Space Applications Centre | Ahmedabad | The SAC deals with the various aspects of the practical use of space technology.[43] Among the fields of research at the SAC are geodesy, satellite based telecommunications, surveying, remote sensing, meteorology, environment monitoring etc.[43] The SAC also operates the Delhi Earth Station, which is located in Delhi and is used for demonstration of various SATCOM experiments in addition to normal SATCOM operations.[45] |

| North-Eastern Space Applications Centre | Shillong | Providing developmental support to North East by undertaking specific application projects using remote sensing, GIS, satellite communication and conducting space science research. |

Test facilities

| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| ISRO Propulsion Complex | Mahendragiri | Formerly called LPSC-Mahendragiri, was declared a separate centre. It handles testing and assembly of liquid propulsion control packages, liquid engines and stages for launch vehicles and satellites.[43] |

Construction and launch facilities

| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| U R Rao Satellite Centre | Bangalore | The venue of eight successful spacecraft projects is also one of the main satellite technology bases of ISRO. The facility serves as a venue for implementing indigenous spacecraft in India.[43] The satellites Aaryabhata, Bhaskara, APPLE, and IRS-1A were constructed at this site, and the IRS and INSAT satellite series are presently under development here. This centre was formerly known as ISRO Satellite Centre.[44] |

| Laboratory for Electro-Optics Systems | Bangalore | The Unit of ISRO responsible for the development of altitude sensors for all satellites. The high precision optics for all cameras and payloads in all ISRO satellites are developed at this laboratory, located at Peenya Industrial Estate, Bangalore. |

| Satish Dhawan Space Centre | Sriharikota | With multiple sub-sites the Sriharikota island facility acts as a launching site for India's satellites.[43] The Sriharikota facility is also the main launch base for India's sounding rockets.[44] The centre is also home to India's largest Solid Propellant Space Booster Plant (SPROB) and houses the Static Test and Evaluation Complex (STEX).[44] The Second Vehicle Assembly Building (SVAB) at Sriharikota is being realised as an additional integration facility, with suitable interfacing to a second launch pad.[46][47] |

| Thumba Equatorial Rocket Launching Station | Thiruvananthapuram | TERLS is used to launch sounding rockets. |

Tracking and control facilities

| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Deep Space Network (IDSN) | Bangalore | This network receives, processes, archives and distributes the spacecraft health data and payload data in real time. It can track and monitor satellites up to very large distances, even beyond the Moon. |

| National Remote Sensing Centre | Hyderabad | The NRSC applies remote sensing to manage natural resources and study aerial surveying.[43] With centres at Balanagar and Shadnagar it also has training facilities at Dehradun acting as the Indian Institute of Remote Sensing.[43] |

| ISRO Telemetry, Tracking and Command Network | Bangalore (headquarters) and a number of ground stations throughout India and the world.[45] | Software development, ground operations, Tracking Telemetry and Command (TTC), and support is provided by this institution.[43] ISTRAC has Tracking stations throughout the country and all over the world in Port Louis (Mauritius), Bearslake (Russia), Biak (Indonesia) and Brunei. |

| Master Control Facility | Bhopal; Hassan | Geostationary satellite orbit raising, payload testing, and in-orbit operations are performed at this facility.[48] The MCF has Earth stations and the Satellite Control Centre (SCC) for controlling satellites.[48] A second MCF-like facility named 'MCF-B' is being constructed at Bhopal.[48] |

| Space Situational Awareness Control Centre | Peenya, Bangalore | A network of telescopes and radars are being set up under the Directorate of Space Situational Awareness and Management to monitor space debris and to safeguard space-based assets. The new facility will end ISRO's dependence on Norad. The sophisticated multi-object tracking radar installed in Nellore, a radar in NE India and telescopes in Thiruvananthapuram, Mount Abu and North India will be part of this network.[49][50] |

Human resource development

| Facility | Location | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) | Dehradun | The Indian Institute of Remote Sensing (IIRS) is a premier training and educational institute set up for developing trained professionals (P.G. and PhD level) in the field of remote sensing, geoinformatics and GPS technology for natural resources, environmental and disaster management. IIRS is also executing many R&D projects on remote sensing and GIS for societal applications. IIRS also runs various outreach programmes (Live & Interactive and e-learning) to build trained skilled human resources in the field of remote sensing and geospatial technologies. |

| Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology (IIST) | Thiruvananthapuram | The institute offers undergraduate and graduate courses in aerospace engineering, avionics and physical sciences. The students of the first three batches of IIST were inducted into different ISRO centres. |

| Development and Educational Communication Unit | Ahmedabad | The centre works for education, research, and training, mainly in conjunction with the INSAT programme.[43] The main activities carried out at DECU include GRAMSAT and EDUSAT projects.[44] The Training and Development Communication Channel (TDCC) also falls under the operational control of the DECU.[45] |

| Space Technology Incubation Centres (S-TICs) at: | Agartala, Jalandhar, Tiruchirappalli | The S-TICs opened at premier technical universities in India to promote startups to build applications and products in tandem with the industry and would be used for future space missions. The S-TIC will bring the industry, academia and ISRO under one umbrella to contribute towards research and development (R&D) initiatives relevant to the Indian Space Programme.[51] |

Regional Academy Centre for Space (RAC-S) at:

|

Jaipur, Guwahati, Kurukshetra, Mangalore, Patna, Varanasi | All these centres are set up in tier-2 cities to create awareness, strengthen academic collaboration and act as incubators for space technology, space science and space applications. The activities of RAC-S will be to maximise use of research potential, infrastructure, expertise, experience and facilitate capacity building. |

Antrix Corporation Limited (Commercial Wing)

Set up as the marketing arm of ISRO, Antrix's job is to promote products, services and technology developed by ISRO.[52][53]

New Space India Limited (Commercial Wing)

Set up for marketing spin-off technologies, tech transfers through industry interface and scale up industry participation in the space programmes.[54]

Other facilities

- Aerospace Command of India (ACI)

- Balasore Rocket Launching Station (BRLS) – Odisha

- Human Space Flight Centre (HSFC), Bangalore.

- Indian National Committee for Space Research (INCOSPAR)

- Indian Regional Navigational Satellite System (IRNSS)

- Indian Space Science Data Centre (ISSDC)

- Integrated Space Cell

- Inter University Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics (IUCAA)

- ISRO Inertial Systems Unit (IISU) – Thiruvananthapuram

- National Deep Space Observation Centre (NDSPO)

- Regional Remote Sensing Service Centres (RRSSC)

- Master Control Facility

Launch vehicles

During the 1960s and 1970s, India initiated its own launch vehicles owing to geopolitical and economic considerations. In the 1960s–1970s, the country developed a sounding rocket, and by the 1980s, research had yielded the Satellite Launch Vehicle-3 and the more advanced Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle (ASLV), complete with operational supporting infrastructure.[55] ISRO further applied its energies to the advancement of launch vehicle technology resulting in the creation of the successful PSLV and GSLV vehicles.

Satellite Launch Vehicle (SLV)

The Satellite Launch Vehicle or SLV is a Small-lift launch vehicle, was a project started in the early 1970s by the Indian Space Research Organisation to develop the technology needed to launch satellites. SLV was intended to reach a height of 400 kilometres (250 mi) and carry a payload of 40 kg (88 lb).[56] The first experimental flight of SLV-3, in August 1979, was a failure.[57] The first successful launch took place on 18 July, 1980.

It was a four-stage rocket with all solid-propellant motors.[57]

The first launch of the SLV took place in Sriharikota on 10 August 1979. The fourth and final launch of the SLV took place on 17 April 1983.

It has taken approximately seven years to realise the vehicle from start. The solid motor case for first and second stage are fabricated from 15 CDV6 steel sheets and third and fourth stages from fibre reinforced plastic.[58]Augmented Satellite Launch Vehicle (ASLV)

Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV)

.jpg)

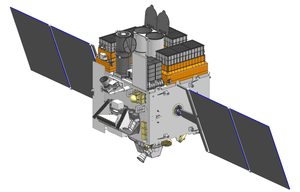

The Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) is an expendable medium-lift launch vehicle designed and operated by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). It was developed to allow India to launch its Indian Remote Sensing (IRS) satellites into sun-synchronous orbits, a service that was, until the advent of the PSLV in 1993, commercially available only from Russia. PSLV can also launch small size satellites into Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO).[63]

Some notable payloads launched by PSLV include India's first lunar probe Chandrayaan-1, India's first interplanetary mission, Mars Orbiter Mission (Mangalyaan) and India's first space observatory, Astrosat.[64]

PSLV has gained credence as a leading provider of rideshare services for small satellites, due its numerous multi-satellite deployment campaigns with auxiliary payloads usually ride sharing along an Indian primary payload.[65] As of December 2019, PSLV has launched 319 foreign satellites from 33 countries.[66] Most notable among these was the launch of PSLV C37 on 15 February 2017, successfully deploying 104 satellites in sun-synchronous orbit, tripling the previous record held by Russia for the highest number of satellites sent to space on a single launch.[67][68]

Payloads can be integrated in tandem configuration employing a Dual Launch Adapter.[69][70] Smaller payloads are also placed on equipment deck and customized payload adapters.[71]Decade-wise summary of PSLV launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failures | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990s | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2000s | 11 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 2010s | 33 | 0 | 1 | 34 |

| Total | 47 | 1 | 2 | 50 |

Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV)

Decade-wise summary of GSLV Launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failures | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000s | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| 2010s | 6 | 0 | 2 | 8 |

GSLV Mark III

.jpg)

The Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV Mk III),[72][73] also referred to as the Launch Vehicle Mark 3 (LVM3),[73] is a three-stage[72] medium-lift launch vehicle developed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO). Primarily designed to launch communication satellites into geostationary orbit,[74] it is also identified as launch vehicle for crewed missions under the Indian Human Spaceflight Programme and dedicated science missions like Chandrayaan-2.[75][76] The GSLV Mk III has a higher payload capacity than the similarly named GSLV Mk II.[77][78][79][80]

After several delays and a sub-orbital test flight on 18 December 2014, ISRO successfully conducted the first orbital test launch of GSLV Mk III on 5 June 2017 from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Andhra Pradesh.[81]

In June 2018, the Union Cabinet approved ₹43.38 billion (US$610 million) to build 10 GSLV Mk III rockets over a five-year period.[82]

GSLV Mk III launched CARE, India's space capsule recovery experiment module, Chandrayaan-2, India's second lunar mission and will be used to carry Gaganyaan, the first crewed mission under Indian Human Spaceflight Programme.Decade-wise summary of GSLV Mark III launches:

| Decade | Successful | Partial success | Failures | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010s | 4 | 0 | 0 | 4[83] |

Satellite programmes

India's first satellite, the Aryabhata, was launched by the Soviet Union on 19 April 1975 from Kapustin Yar using a Cosmos-3M launch vehicle. This was followed by the Rohini series of experimental satellites, which were built and launched indigenously. At present, ISRO operates a large number of Earth observation satellites.

The INSAT series

The Indian National Satellite System (INSAT) is a series of multipurpose geostationary satellites built and launched by ISRO to satisfy the telecommunications, broadcasting, meteorology and search-and-rescue needs of India. Commissioned in 1983, INSAT is the largest domestic communication system in the Asia-Pacific Region. It is a joint venture of the Department of Space, Department of Telecommunications, India Meteorological Department, All India Radio and Doordarshan. The overall coordination and management of INSAT system rests with the Secretary-level INSAT Coordination Committee.

The IRS series

The Indian Remote Sensing satellites (IRS) are a series of Earth observation satellites, built, launched and maintained by ISRO. The IRS series provides remote sensing services to the country and is the largest collection of remote sensing satellites for civilian use in operation today in the world. All the satellites are placed in polar Sun-synchronous orbit and provide data in a variety of spatial, spectral and temporal resolutions to enable several programmes to be undertaken relevant to national development. The initial versions are composed of the 1 (A, B, C, D) nomenclature. The later versions are named based on their area of application including OceanSat, CartoSat, ResourceSat.

Radar Imaging Satellites

ISRO currently operates three Radar Imaging Satellites (RISAT). RISAT-1 was launched from Sriharikota Spaceport on 26 April 2012 on board a PSLV. RISAT-1 carries a C band synthetic-aperture radar (SAR) payload, operating in a multi-polarisation and multi-resolution mode and can provide images with coarse, fine and high spatial resolutions.[84] RISAT-2 which was launched in 2009 due to delay with the indigenously developed C band SAR for RISAT-1. The X-band SAR used by RISAT-2 was obtained from IAI in return for launch services for TecSAR satellite.[85] PSLV-C46 launched the third satellite RISAT-2B intended to replace RISAT-2, on 22 May 2019 at 0000 (UTC) from Satish Dhawan Space Centre with an indigenously developed Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) operating in X Band.[86] This will be followed by a new series of high-resolution optical surveillance satellites called Cartosat-3 series.[87]

Other satellites

ISRO has also launched a set of experimental geostationary satellites known as the GSAT series. Kalpana-1, ISRO's first dedicated meteorological satellite,[88] was launched on a Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle on 12 September 2002.[89] The satellite was originally known as MetSat-1.[90] In February 2003 it was renamed to Kalpana-1 by the Indian prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in memory of Kalpana Chawla – a NASA astronaut of Indian origin who perished in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.

ISRO also launched the Indo-French satellite SARAL on 25 February 2013. SARAL (or "Satellite with ARgos and AltiKa") is a cooperative altimetry technology mission. It is being used for monitoring the oceans' surface and sea levels. AltiKa measures ocean surface topography with an accuracy of 8 mm, against 2.5 cm on average using altimeters, and with a spatial resolution of 2 km.[91][92]

In June 2014, ISRO launched French Earth Observation Satellite SPOT-7 (mass 714 kg) along with Singapore's first nano satellite VELOX-I, Canada's satellite CAN-X5, Germany's satellite AISAT, via the PSLV-C23 launch vehicle. It was ISRO's 4th commercial launch.[93][94]

South Asia Satellite

The South Asia Satellite (GSAT-9) is a geosynchronous communications satellite by ISRO for the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) region. The satellite was launched on 5 May 2017. During the 18th SAARC summit held in Nepal in 2014, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi mooted the idea of a satellite serving the needs of SAARC member nations, part of his 'neighbourhood first' policy. One month after sworn in as the prime minister of India, in June 2014 Modi asked ISRO to develop a SAARC satellite, which can be dedicated as a 'gift' to the neighbors.

It is a satellite for the SAARC region with 12 Ku-band transponders (36 MHz each) and launch using the Indian Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle GSLV Mk-II. The total cost of launching the satellite is estimated to be about ₹2,350,000,000 (₹2.35 billion). The cost associated with the launch was met by the Government of India. The satellite enables full range of applications and services in the areas of telecommunication and broadcasting applications such as television (TV), direct-to-home (DTH), very small aperture terminals (VSATs), tele-education, telemedicine and disaster management support.

GAGAN satellite navigation system

The Ministry of Civil Aviation has decided to implement an indigenous Satellite-Based Regional GPS Augmentation System also known as Space-Based Augmentation System (SBAS) as part of the Satellite-Based Communications, Navigation, Surveillance and Air Traffic Management plan for civil aviation. The Indian SBAS system has been given an acronym GAGAN – GPS Aided GEO Augmented Navigation. A national plan for satellite navigation including implementation of Technology Demonstration System over the Indian air space as a proof of concept has been prepared jointly by Airports Authority of India and ISRO. Technology Demonstration System was completed during 2007 by installing eight Indian Reference Stations at eight Indian airports and linked to the Master Control Centre located near Bangalore.

The first GAGAN navigation payload was fabricated and it was proposed to be flown on GSAT-4 in April 2010. However, GSAT-4 was not placed in orbit as GSLV Mk II-D3 could not complete the mission. Two more GAGAN payloads were to be subsequently flown, one each on two geostationary satellites, GSAT-8 and GSAT-10.

The third GAGAN payload satellite GSAT-15 with an estimated lifespan of 12 years similar to GSAT-10 was successfully launched on 10 November 2015 at 21:34:07 UTC aboard an Ariane 5 rocket.

IRNSS satellite navigation system (NAVIC)

IRNSS with an operational name NAVIC is an independent regional navigation satellite system developed by India. It is designed to provide accurate position information service to users in India as well as the region extending up to 1500 km from its borders, which is its primary service area. IRNSS provides two types of services, namely, Standard Positioning Service (SPS) and Restricted Service (RS) and provides a position accuracy of better than 20 m in the primary service area.[95] It is an autonomous regional satellite navigation system being developed by Indian Space Research Organisation, which is under total control of Indian government. The requirement of such a navigation system is driven by the fact that access to global navigation systems like GPS is not guaranteed in hostile situations. ISRO initially planned to launch the constellation of satellites between 2012 and 2014 but the project got delayed by nearly two years.

On 1 July 2013, ISRO launched from Sriharikota the first Indian navigation satellite, the IRNSS-1A aboard a PSLV-C22. The constellation would comprise seven satellites built on the I-1K bus, each weighing around 1,450 kilograms, with three satellites in the Geostationary Earth Orbit (GEO) and four in Geosynchronous Earth orbit(GSO).[96]

On 4 April 2014, ISRO launched IRNSS-1B from Sriharikota, its second of seven IRNSS series. 19 minutes after launch, the PSLV-C24 was injected into its orbit. IRNSS-1C was launched on 16 October 2014, and IRNSS-1D on 28 March 2015.[97]

On 20 January 2016, IRNSS-1E was launched aboard PSLV-C31. On 10 March 2016, IRNSS-1F was launched aboard PSLV-C32. On 28 April 2016, IRNSS-1G was launched aboard PSLV-XL-C33; this satellite is the seventh and the last in the IRNSS system and completes India's own navigation system.

ISRO was in the process of developing four back-up satellites to the constellation of existing IRNSS satellites.[98]

On 31 August 2017, ISRO failed in its attempt to launch its eighth regional navigation satellite (IRNSS-1H). The satellite got stuck in the fourth stage of the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle–PSLV-C39. A replacement satellite, IRNSS-1I, was successfully placed into orbit on 12 April 2018.[99]

To boost the accuracy of NAVIC system, ISRO is likely to extend the Indian Regional Navigation Satellite System programme with new IRNSS series which will be entirely a new project as per chairman K Sivan. The new IRNSS series is not meant to extend its coverage beyond the regional boundaries extending up to 1500 kilometers.[100]

Human Spaceflight Programme

In 2009, the Indian Space Research Organisation proposed a budget of ₹12,400 crore (US$1.7 billion) for its human spaceflight programme.[101] According to the Space Commission, which recommended the budget, an uncrewed flight will be launched after seven years from the final approval[102] and a crewed mission will be launched after seven years of funding.[103][104] If realised in the stated time-frame, India will become the fourth nation, after the USSR, USA and China, to successfully carry out crewed missions indigenously.

Prime Minister of India Narendra Modi announced in his Independence Day address of 15 August 2018 that India will send astronauts into space by 2022 on the new Gaganyaan spacecraft.[105] After the announcement, ISRO chairman, Sivan, said ISRO has developed most of the technologies needed such as crew module and crew escape system, and that the project would cost less than Rs. 100 billion and would include sending at least 3 Indians to space, 300–400 km above in a spacecraft for at least seven days using a GSLV Mk-III launch vehicle.[106][107] The chance of a female being a member of the first crew is "very high" according to the scientific secretary to the Indian chairman, R. Umamaheswaran.[108]

Technology demonstrations

The Space Capsule Recovery Experiment (SCRE or more commonly SRE or SRE-1)[109] is an experimental spacecraft that was launched on 10 January 2007 using the PSLV C7 rocket, along with three other satellites. It remained in orbit for 12 days before re-entering the Earth's atmosphere and splashing down into the Bay of Bengal.[110]

The SRE-1 was designed to demonstrate the capability to recover an orbiting space capsule and the technology for performing experiments in the microgravity conditions of an orbiting platform. It was also intended to test thermal protection, navigation, guidance, control, deceleration, and flotation systems, as well as study hypersonic aerothermodynamics, management of communication blackouts, and recovery operations. A follow-up project named SRE-2 was canceled mid-way after years of delay.[111]

on 18 December 2014, ISRO launched the Crew Module Atmospheric Re-entry Experiment aboard the GSLV Mk3 for a sub-orbital flight.[112][113] The crew module separated from the rocket at an altitude of 126 km and underwent free fall. The module heat shield experienced temperature in excess of 1600 °C. Parachutes were deployed at an altitude of 15 km to slow down the module which performed a splashdown in the Bay of Bengal. This flight was used to test orbital injection, separation and re-entry procedures and systems of the Crew Capsule. Also tested were the capsule separation, heat shields and aerobraking systems, deployment of parachute, retro-firing, splashdown, flotation systems and procedures to recover the Crew Capsule from the Bay of Bengal.[114][115]

On 5 July 2018, ISRO conducted a pad abort test of their launch abort system (LAS) at Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota. This is the first in a series of tests to qualify the critical crew escape system technology for future crewed missions. The LAS is designed to quickly pull out the crew to safety in case of emergency.[116]

Astronaut training and other facilities

The newly established Human Space Flight Centre (HSFC) will coordinate the IHSF campaign.[117][118] ISRO will set up an astronaut training centre in Bangalore to prepare personnel for flights on board the crewed vehicle. The centre will use simulation facilities to train the selected astronauts in rescue and recovery operations and survival in zero gravity, and will undertake studies of the radiation environment of space. ISRO will build centrifuges to prepare astronauts for the acceleration phase of the launch. Existing launch facilities in Satish Dhawan Space Centre will be upgraded for the Indian Human Spaceflight campaign.[119] Human Space Flight Centre and Glavcosmos signed an agreement on 1 July 2019 for the selection, support, medical examination and space training of Indian astronauts.[120] An ISRO Technical Liaison Unit (ITLU) will be setup in Moscow to facilitate the development of some key technologies and establishment of special facilities which are essential to support life in space.[121]

Crewed spacecraft

ISRO is working towards an orbital crewed spacecraft that can operate for seven days in a low Earth orbit. The spacecraft, called Gaganyaan (गगनयान), will be the basis of the Indian Human Spaceflight Programme. The spacecraft is being developed to carry up to three people, and a planned upgraded version will be equipped with a rendezvous and docking capability. In its maiden crewed mission, ISRO's largely autonomous 3-ton spacecraft will orbit the Earth at 400 km in altitude for up to seven days with a two-person crew on board. The crewed mission is planned to be launched on ISRO's GSLV Mk III in 2022.[122]

Space station

India plans to build a space station as a follow-up programme of the Gaganyaan mission. ISRO chairman K. Sivan has said that India will not join the International Space Station program and will instead build a 20 tonne space station on its own.[123][124] It is expected to be placed in a low earth orbit of 400 kilometres (250 mi) altitude and be capable of harbouring three humans for 15–20 days. Rough time-frame is five to seven years after completion of Gaganyaan project.[125][126]

Planetary sciences and astronomy

India's space era dawned when the first two-stage sounding rocket was launched from Thumba in 1963.

There is a national balloon launching facility at Hyderabad jointly supported by TIFR and ISRO. This facility has been extensively used for carrying out research in high energy (i.e., X- and gamma-ray) astronomy, IR astronomy, middle atmospheric trace constituents including CFCs & aerosols, ionisation, electric conductivity and electric fields.[127]

The flux of secondary particles and X-ray and gamma-rays of atmospheric origin produced by the interaction of the cosmic rays is very low. This low background, in the presence of which one has to detect the feeble signal from cosmic sources is a major advantage in conducting hard X-ray observations from India. The second advantage is that many bright sources like Cyg X-1, Crab Nebula, Scorpius X-1 and Galactic Centre sources are observable from Hyderabad due to their favourable declination. With these considerations, an X-ray astronomy group was formed at TIFR in 1967 and development of an instrument with an orientable X-ray telescope for hard X-ray observations was undertaken. The first balloon flight with the new instrument was made on 28 April 1968 in which observations of Scorpius X-1 were successfully carried out. In a succession of balloon flights made with this instrument between 1968 and 1974 a number of binary X-ray sources including Cyg X-1 and Her X-1, and the diffuse cosmic X-ray background were studied. Many new and astrophysically important results were obtained from these observations.[128]

ISRO played a role in the discovery of three species of bacteria in the upper stratosphere at an altitude of between 20–40 km. The bacteria, highly resistant to ultra-violet radiation, are not found elsewhere on Earth, leading to speculation on whether they are extraterrestrial in origin.[129] These three bacteria can be considered to be extremophiles. The bacteria were named as Bacillus isronensis in recognition of ISRO's contribution in the balloon experiments, which led to its discovery, Bacillus aryabhata after India's celebrated ancient astronomer Aryabhata and Janibacter hoylei after the distinguished astrophysicist Fred Hoyle.[130]

Astrosat

Astrosat is India's first multi wavelength space observatory and full-fledged astronomy satellite. Its observation study includes active galactic nuclei, hot white dwarfs, pulsations of pulsars, binary star systems, supermassive black holes located at the centre of the galaxies, etc.[131]

XPoSat

The X-ray Polarimeter Satellite (XPoSat) is a planned mission to study polarisation. It is planned to have a mission life of five years and is planned to be launched in 2021.[132] The spacecraft is planned to carry the Polarimeter Instrument in X-rays (POLIX) payload which will study the degree and angle of polarisation of bright astronomical X-ray sources in the energy range 5–30 keV.[133]

Exoworlds

Exoworlds is a joint proposal by ISRO, IIST and the University of Cambridge for a space telescope dedicated for atmospheric studies of exoplanets. The proposal is aiming for readiness by 2025.[134][135]

Extraterrestrial exploration

Chandrayaan-1

.jpg)

Chandrayaan-1 was India's first mission to the Moon. The robotic lunar exploration mission included a lunar orbiter and an impactor called the Moon Impact Probe. ISRO launched the spacecraft using a modified version of the PSLV on 22 October 2008 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre, Sriharikota. The vehicle was inserted into lunar orbit on 8 November 2008. It carried high-resolution remote sensing equipment for visible, near infrared, and soft and hard X-ray frequencies. During its 312 days operational period (2 years planned), it surveyed the lunar surface to produce a complete map of its chemical characteristics and 3-dimensional topography. The polar regions were of special interest, as they possibly had ice deposits. The spacecraft carried 11 instruments: 5 Indian and 6 from foreign institutes and space agencies (including NASA, ESA, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, Brown University and other European and North American institutes/companies), which were carried free of cost. Chandrayaan-1 became the first lunar mission to discover existence of water on the Moon.[136] The Chandrayaan-166 team was awarded the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics SPACE 2009 award,[137] the International Lunar Exploration Working Group's International Co-operation award in 2008,[138] and the National Space Society's 2009 Space Pioneer Award in the science and engineering category.[139][140]

Mars Orbiter Mission (Mangalayaan)

Main article: Mars Orbiter Mission

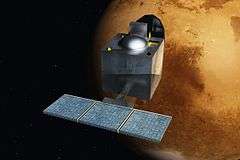

The Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM), informally known as Mangalayaan, was launched into Earth orbit on 5 November 2013 by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and has entered Mars orbit on 24 September 2014.[141] India thus became the first country to enter Mars orbit on its first attempt. It was completed at a record low cost of $74 million.[142]

MOM was placed into Mars orbit on 24 September 2014 at 8:23 am IST. The spacecraft had a launch mass of 1,337 kg (2,948 lb), with 15 kg (33 lb) of five scientific instruments as payload.

The National Space Society awarded the Mars Orbiter Mission team the 2015 Space Pioneer Award in the science and engineering category.[143][144]

Chandrayaan-2

Chandrayaan-2 is second mission to the Moon, which included an orbiter, a lander and a rover. Chandrayaan-2 was launched on a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV-MkIII) on 22 July 2019, consisted of a lunar orbiter, the Vikram lander, and the Pragyan lunar rover, all of which were developed in India.[145][146] It is the first mission meant to explore the little-explored lunar south pole region.[147] The main objective of the Chandrayaan-2 mission is to demonstrate ISRO's ability to soft-land on the lunar surface and operate a robotic rover on the surface. Some of its scientific aims are to conduct studies of lunar topography, mineralogy, elemental abundance, the lunar exosphere, and signatures of hydroxyl and water ice.[148]

The Vikram lander, carrying the Pragyan rover, was scheduled to land on the near side of the Moon, in a south polar region at a latitude of about 70° south at approximately 1:50 am(IST) on 7 September 2019. However, the lander deviated from its intended trajectory starting from an altitude of 2.1 kilometres (1.3 mi), and telemetry was lost seconds before touchdown was expected.[149] A review board concluded that the crash-landing was caused by a software glitch.[150] The lunar orbiter was efficiently positioned in an optimal lunar orbit, extending its expected service time from one year to seven years.[151] There will be another attempt for soft landing on moon at the end of 2020 or early 2021, but without an orbiter.[152]

Future projects

ISRO plans to launch a number of Earth observation satellites in the near future. It will also undertake the development of new launch vehicles, a crewed orbital vehicle (Gaganyaan), a space station[153] and probes to Mars, Venus and near-Earth objects.

Forthcoming satellites

| Satellite name | Launch vehicle | Year | Purpose | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RISAT-2BR2 | PSLV | 2020 | SAR imaging | |

| Oceansat-3 | PSLV | 2020 | Earth observation | |

| GSAT-20 | GSLV Mk III | 2020 | Communications | |

| IRNSS-1J | PSLV | TBD | Navigation | |

| GISAT 1 | GSLV Mk II | 2020 | Earth observation | Geospatial imagery to facilitate continuous observation of Indian sub-continent, quick monitoring of natural hazards and disaster. |

| GISAT 2 | GSLV Mk II | 2020 | Earth observation | Geospatial imagery to facilitate continuous observation of Indian sub-continent, quick monitoring of natural hazards and disaster. |

| IDRSS | GSLV Mk III | 2020 | Data relay and satellite tracking constellation | Facilitates continuous real-time communication between Low Earth orbit bound spacecrafts to the ground station as well as inter-satellite communication. Such a satellite in geostationary orbit can track a low altitude spacecraft up to almost half of its orbit. |

| GSAT-12R | TBD | 2020 | Communications | [154] |

| NISAR | GSLV Mk II | 2022 | Earth observation | NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) is a joint project between NASA and ISRO to co-develop and launch a dual frequency synthetic aperture radar satellite to be used for remote sensing. It is notable for being the first dual band radar imaging satellite. |

| DISHA | PSLV | 2024–25[155] | Aeronomy | Disturbed and quite-type Ionosphere System at High Altitude (DISHA) satellite constellation with two satellites in 450 km LEO.[156] |

| AHySIS-2 | PSLV | 2024 | Earth observation | Follow-up to HySIS hyperspectral Earth imaging satellite.[157] |

Future extraterrestrial exploration

ISRO plans to follow up with Mars Orbiter Mission 2, and is assessing missions to Venus, the Sun, and near-Earth objects such as asteroids and comets.[158]

| Destination | Craft name | Launch vehicle | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sun | Aditya-L1 | PSLV-XL | 2020 |

| Moon | Chandrayaan 3 | GSLV | 2021 |

| Venus | Shukrayaan-1 | GSLV III | 2023 |

| Jupiter | TBD | TBD | TBD |

| Mars | Mars Orbiter Mission 2 (Mangalyaan 2) | GSLV III | 2024 |

Aditya-L1

ISRO plans to carry out a mission to the Sun by the year 2020.[160][161] The probe is named Aditya-L1 (Sanskrit: आदित्य L१) and will have a mass of about 400 kg (880 lb).[162] It is the first Indian space-based solar coronagraph to study the corona in visible and near-IR bands. Launch of the Aditya mission was planned during the heightened solar activity period in 2012, but was postponed to 2021 due to the extensive work involved in the fabrication, and other technical aspects. The main objective of the mission is to study coronal mass ejections (CMEs), their properties (the structure and evolution of their magnetic fields for example), and consequently constrain parameters that affect space weather.

Venus and Jupiter

ISRO is in the process of conducting conceptual studies to send a spacecraft to Jupiter or Venus.

Shukrayaan 1

ISRO is assessing an orbiter mission to Venus called Shukrayaan-1, that could launch as early as 2023 to study its atmosphere.[163] Some budget has been allocated to perform preliminary studies as part of 2017–18 Indian budget under Space Sciences,[164][165][166] and solicitations for potential instruments were requested in 2017[167] and in 2018.

Jupiter

The ideal launch window to send a spacecraft to Jupiter occurs every 33 months. If the mission to Jupiter is launched, a flyby of Venus would be required.[168]

Mangalyaan 2

The next Mars mission, Mars Orbiter Mission 2, also called Mangalyaan 2 (Sanskrit: मंगलयान-२), will be launched in 2024.[156] It will have a less elliptical orbit around Mars and could weigh seven times more than the first mission.[169] This orbiter mission will facilitate the community to address several open science problems. The science payload of the planned satellite is estimated at no more than 100 kg (220 lb).

Joint Lunar Polar Exploration

ISRO signed an Implementation Arrangement (IA) in December 2017 for pre-phase A, phase A study and completed the feasibility report in March 2018 with Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)[170] to explore the polar regions of Moon for water[171] with a Joint Lunar Polar Exploration mission that would be launched by 2024.[172][173]

Space transportation

Small Satellite Launch Vehicle

Small Satellite Launch Vehicle or SSLV is in development for the commercial launch of small satellites with a payload of 500 kg to low Earth orbit. SSLV would be a four-staged vehicle with three solid propellant-based stages and a Velocity Trimming Module. The maiden flight is expected in July 2019 from Satish Dhawan Space Centre.[174][175]

Reusable Launch Vehicle-Technology Demonstrator (RLV-TD)

As a first step towards realising a two-stage-to-orbit (TSTO) fully re-usable launch vehicle, a series of technology demonstration missions have been conceived. For this purpose, the winged Reusable Launch Vehicle Technology Demonstrator (RLV-TD) has been configured. The RLV-TD is acting as a flying testbed to evaluate various technologies such as hypersonic flight, autonomous landing, powered cruise flight, and hypersonic flight using air-breathing propulsion.

First in the series of demonstration trials was the Hypersonic Flight Experiment (HEX). ISRO launched the prototype's test flight from the Sriharikota spaceport in February 2016. The prototype, called RLV-TD, weighs around 1.5 tonnes and flew up to a height of 70 km.[176] The test flight, known as HEX, was completed on 23 May 2016. A scaled up version of could serve as fly-back booster stage for their winged TSTO concept.[177]

Unified Launch Vehicle

The Unified Launch Vehicle (ULV) is a launch vehicle in development by ISRO. The project's core objective is to design a modular architecture that will enable the replacement of the PSLV, GSLV Mk II and GSLV Mk III with a single family of launchers. The SCE-200 engine can even be clustered for heavy launch configuration. The ULV will be able to launch 6000 kg to 10,000 kg of payload into GTO. This will mark the renunciation of the liquid stage with Vikas engine, which uses toxic UDMH and N2O4.

Future Super-heavy Lift Launch Vehicle

ISRO is conducting preliminary research for the development of a Super heavy-lift launch vehicle which is planned to have a lifting capacity of over 50–60 tonnes into an unspecified orbit.[178]

Space Technology Incubation Centre

ISRO has opened Space Technology Incubation Centres (S-TIC) at premier technical universities in India which will incubate startups to build applications and products in tandem with the industry and would be used for future space missions. The S-TIC will bring the industry, academia and ISRO under one umbrella to contribute towards research and development (R&D) initiatives relevant to the Indian Space Programme. S-TICs are at the National Institute of Technology, Agartala serving for east region, National Institute of Technology, Jalandhar for the north region, and the National Institute of Technology, Tiruchirappalli for the south region of India.[51]

Applications

Telecommunication

India uses its satellite communication network – one of the largest in the world – for applications such as land management, water resources management, natural disaster forecasting, radio networking, weather forecasting, meteorological imaging and computer communication.[179] Business, administrative services, and schemes such as the National Informatics Centre (NIC) are direct beneficiaries of applied satellite technology.[180] Dinshaw Mistry, on the subject of practical applications of the Indian space program, writes:

"The INSAT-2 satellites also provide telephone links to remote areas; data transmission for organisations such as the National Stock Exchange; mobile satellite service communications for private operators, railways, and road transport; and broadcast satellite services, used by India's state-owned television agency as well as commercial television channels. India's EDUSAT (Educational Satellite), launched aboard the GSLV in 2004, was intended for adult literacy and distance learning applications in rural areas. It augmented and would eventually replace such capabilities already provided by INSAT-3B."

Resource management

The IRS satellites have found applications with the Indian Natural Resource Management program, with Regional Remote Sensing Service Centres in five Indian cities, and with Remote Sensing Application Centres in twenty Indian states that use IRS images for economic development applications. These include environmental monitoring, analysing soil erosion and the impact of soil conservation measures, forestry management, determining land cover for wildlife sanctuaries, delineating groundwater potential zones, flood inundation mapping, drought monitoring, estimating crop acreage and deriving agricultural production estimates, fisheries monitoring, mining and geological applications such as surveying metal and mineral deposits, and urban planning.

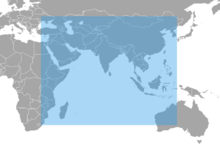

Military

Integrated Space Cell, under the Integrated Defence Staff headquarters of the Indian Ministry of Defence,[181] has been set up to utilise more effectively the country's space-based assets for military purposes and to look into threats to these assets.[182][183] This command will leverage space technology including satellites. Unlike an aerospace command, where the air force controls most of its activities, the Integrated Space Cell envisages cooperation and coordination between the three services as well as civilian agencies dealing with space.[181] With 14 satellites, including GSAT-7A for the exclusive military use and the rest as dual use satellites, India has the fourth largest number of satellites active in the sky which includes satellites for the exclusive use of Indian Air Force and Indian Navy respectively.[184] GSAT-7A, an advanced military communications satellite exclusively for the Indian Air Force,[185] is similar to Indian Navy's GSAT-7, and GSAT-7A will enhance Network-centric warfare capabilities of the Indian Air Force by interlinking different ground radar stations, ground airbase and Airborne early warning and control (AWACS) aircraft such as Beriev A-50 Phalcon and DRDO AEW&CS.[185][186] GSAT-7A will also be used by Indian Army's Aviation Corps for its helicopters and UAV's operations.[185][186] In 2013, ISRO launched GSAT-7 for the exclusive use of the Indian Navy to monitor the Indian Ocean Region (IOR) with the satellite's 2,000 nautical mile 'footprint' and real-time input capabilities to Indian warships, submarines and maritime aircraft.[184] To boost the network-centric operations of the IAF, ISRO launched GSAT-7A on 19 December 2018.[187][184] The RISAT series of radar-imaging earth observation satellites is also meant for Military use.[188] ISRO launched EMISAT on 1 April 2019. EMISAT is an electronic intelligence (ELINT) satellite which has a weight of 436-kg. It will help improve the situational awareness of the Indian Armed Forces by providing information and location of hostile radars.[189]

India's satellites and satellite launch vehicles have had military spin-offs. While India's 93–124-mile (150–200-kilometre) range Prithvi missile is not derived from the Indian space programme, the intermediate range Agni missile is drawn from the Indian space programme's SLV-3. In its early years, when headed by Vikram Sarabhai and Satish Dhawan, ISRO opposed military applications for its dual-use projects such as the SLV-3. Eventually, the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) based missile programme borrowed human resources and technology from ISRO. Missile scientist A.P.J. Abdul Kalam (elected president of India in 2002), who had headed the SLV-3 project at ISRO, moved to DRDO to direct India's missile programme. About a dozen scientists accompanied Kalam from ISRO to DRDO, where he designed the Agni missile using the SLV-3's solid fuel first stage and a liquid-fuel (Prithvi-missile-derived) second stage. The IRS and INSAT satellites were primarily intended and used for civilian-economic applications, but they also offered military spin-offs. In 1996 New Delhi's Ministry of Defence temporarily blocked the use of IRS-1C by India's environmental and agricultural ministries to monitor ballistic missiles near India's borders. In 1997 the Indian Air Force's "Airpower Doctrine" aspired to use space assets for surveillance and battle management.[190]

Academic

Institutions like the Indira Gandhi National Open University and the Indian Institutes of Technology use satellites for scholarly applications.[191] Between 1975 and 1976, India conducted its largest sociological programme using space technology, reaching 2400 villages through video programming in local languages aimed at educational development via ATS-6 technology developed by NASA.[192] This experiment—named Satellite Instructional Television Experiment (SITE)—conducted large scale video broadcasts resulting in significant improvement in rural education.[192] Education could reach far remote rural places with the help of above programs.

Telemedicine

ISRO has applied its technology for telemedicine, directly connecting patients in rural areas to medical professionals in urban locations via satellites.[191] Since high-quality healthcare is not universally available in some of the remote areas of India, the patients in remote areas are diagnosed and analysed by doctors in urban centers in real time via video conferencing.[191] The patient is then advised medicine and treatment.[191] The patient is then treated by the staff at one of the 'super-specialty hospitals' under instructions from the doctor.[191] Mobile telemedicine vans are also deployed to visit locations in far-flung areas and provide diagnosis and support to patients.[191]

Biodiversity Information System

ISRO has also helped implement India's Biodiversity Information System, completed in October 2002.[193] Nirupa Sen details the program: "Based on intensive field sampling and mapping using satellite remote sensing and geospatial modeling tools, maps have been made of vegetation cover on a 1: 250,000 scale. This has been put together in a web-enabled database that links gene-level information of plant species with spatial information in a BIOSPEC database of the ecological hot spot regions, namely northeastern India, Western Ghats, Western Himalayas and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. This has been made possible with collaboration between the Department of Biotechnology and ISRO."[193]

Cartography

The Indian IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was equipped with high-resolution panchromatic equipment to enable it for cartographic purposes.[33] IRS-P5 (CARTOSAT-1) was followed by a more advanced model named IRS-P6 developed also for agricultural applications.[33] The CARTOSAT-2 project, equipped with single panchromatic camera that supported scene-specific on-spot images, succeeded the CARTOSAT-1 project.[194]

International cooperations

ISRO has had international cooperations since its inception. Some instances are listed below:

- Establishment of TERLS, conduct of SITE & STEP, launches of Aryabhata, Bhaskara, APPLE, IRS-IA and IRS-IB/ satellites, crewed space mission, etc.

- ISRO operates LUT/MCC under the international COSPAS/SARSAT Programme for Search and Rescue.

- India has established a Centre for Space Science and Technology Education in Asia and the Pacific (CSSTE-AP) that is sponsored by the United Nations.

- India hosted the Second UN-ESCAP Ministerial Conference on Space Applications for Sustainable Development in Asia and the Pacific in November 1999.

- India is a member of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space, Cospas-Sarsat, International Astronautical Federation, Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), International Space University, and the Committee on Earth Observation Satellite (CEOS).[195]

- Chandrayaan-1 carried scientific payloads from NASA, ESA, Bulgarian Space Agency, and other institutions/companies in North America and Europe.

- The United States government on 24 January 2011, removed several Indian government agencies, including ISRO, from the so-called Entity List, in an effort to drive hi-tech trade and forge closer strategic ties with India.[196]

- ISRO carries out joint operations with foreign space agencies, such as the Indo-French Megha-Tropiques Mission.[195]

- The planned 2022 launch of a NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar (NISAR) satellite mission to make global measurements of the causes and consequences of land surface changes. A planned pathway for future joint missions with NASA to explore Mars.[197]

- Contributing to planned BRICS virtual constellation for remote sensing.[198][199]

Antrix Corporation, the commercial and marketing arm of ISRO, handles both domestic and foreign deals.[200]

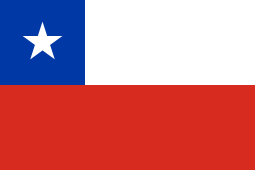

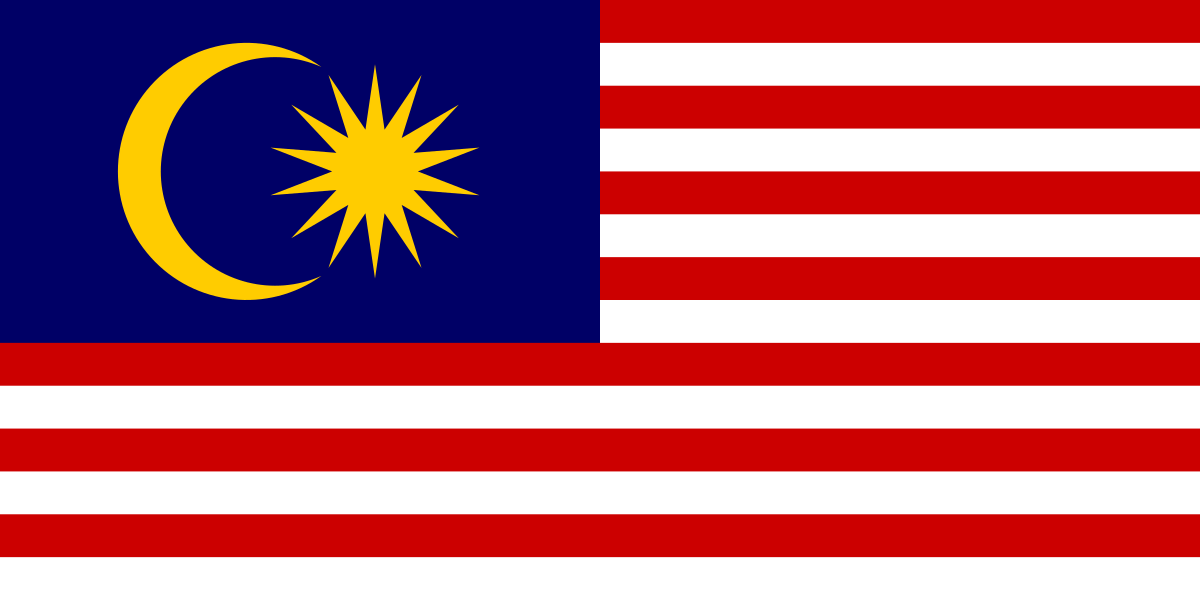

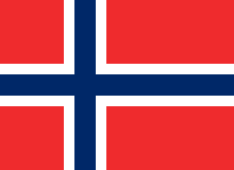

Formal cooperative arrangements in the form of memoranda of understanding or framework agreements have been signed with the following countries[201]

.svg.png)

.svg.png)

The following foreign organisations also have signed various framework agreements with ISRO:

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)

- EUMETSAT (European Organisation for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites)

- European Space Agency

In the 39th Scientific Assembly of Committee on Space Research held in Mysore, ISRO chairman K. Radhakrishnan called upon international synergy in space missions in view of their prohibitive cost. He also mentioned that ISRO is gearing up to meet the growing demand of service providers and security agencies in a cost-effective manner.[202]

ISRO satellites launched by foreign agencies

Several ISRO satellites have been launched by foreign space agencies (of Europe, USSR / Russia, and United States). The details (as of December 2016) are given in the tables below.[203]

| Launch vehicle family | Satellites launched | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Earth observation | Experimental | Other | Total | |

| Europe | |||||

| Ariane | 20 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 21 |

| USSR / Russia | |||||

| Interkosmos | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Vostok | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Molniya | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| USA | |||||

| Delta | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Space Shuttle | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Total | 23 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 30 |

ISRO satellites that were launched by foreign agencies, are listed in the table below.

| No. | Satellite's name | Launch vehicle | Launch agency | Country / region of launch agency | Launch date | Launch mass | Power | Orbit type | Mission life | Other information | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Aryabhata | Kosmos-3M | USSR | 19 April 1975 | 360 kg | 46 W | Low Earth orbit | [204] | |||

| 2. | Bhaskara-1 | Kosmos-3M | USSR | 7 June 1979 | 442 kg | 47 W | Low Earth orbit | 1 year | [205] | ||

| 3. | Apple | Ariane 1

L-03 |

Arianespace | Europe | 19 June 1981 | 670 kg | 210 W | Geosynchronous | 2 years | [206][207] | |

| 4. | Bhaskara-2 | Kosmos-3M | USSR | 20 November 1981 | 444 kg | 47 W | Low Earth orbit | 1 year | [208] | ||

| 5. | INSAT-1A | Delta 3910 | McDonnell-Douglas | USA | 10 April 1982 | 1,152 kg with propellants (550 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [209] | |

| 6. | INSAT-1B | STS-8 | USA | 30 August 1983 | 1,152 kg with propellants (550 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [210] | ||

| 7. | IRS-1A | Vostok-2 | USSR | 17 March 1988 | 975 kg | 620 W | Sun-synchronous | 7 years | [211] | ||

| 8. | INSAT-1C | Ariane 3

V-24/L-23 |

Arianespace | Europe | 22 July 1988 | 1,190 kg with propellants (550 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [212] | |

| 9. | INSAT-1D | Delta 4925 | McDonnell-Douglas | USA | 12 June 1990 | 1,190 kg with propellants (550 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | [213] | |

| 10. | IRS-1B | Vostok-2 | USSR | 29 August 1991 | 975 kg | 600 W | Sun-synchronous | 12 years | [214] | ||

| 11. | INSAT-2A | Ariane 4

V-51/423 |

Arianespace | Europe | 10 July 1992 | 1,906 kg with propellants (905 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [215] | |

| 12. | INSAT-2B | Ariane 4

V-58/429 |

Arianespace | Europe | 22 July 1993 | 1,906 kg with propellants (916 kg dry mass) | 1000 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [216] | |

| 13. | INSAT-2C | Ariane 4

V-81/453 |

Arianespace | Europe | 6 December 1995 | 2,106 kg with propellants (946 kg dry mass) | 1450 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [217] | |

| 14. | IRS-1C | Molniya-M | Russia | 28 December 1995 | 1250 kg | 813 W | Sun-synchronous | 7 years | [218] | ||

| 15. | INSAT-2D | Ariane 4

V-97/468 |

Arianespace | Europe | 3 June 1997 | 2,079 kg with propellants (995 kg dry mass) | 1540 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | [219] | |

| 16. | INSAT-2E | Ariane 4

V-117/486 |

Arianespace | Europe | 2 April 1999 | 2,550 kg with propellants (1,150 kg dry mass) | 2150 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | [220] | |

| 17. | INSAT-3B | Ariane 5

V-128 |

Arianespace | Europe | 21 March 2000 | 2,070 kg with propellants (970 kg dry mass) | 1712 W | Geosynchronous | 10 years | [221] | |

| 18. | INSAT-3C | Ariane 4

V-147 |

Arianespace | Europe | 23 January 2002 | 2,750 kg with propellants (1,220 kg dry mass) | 2765 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | [222] | |

| 19. | INSAT-3A | Ariane 5

V-160 |

Arianespace | Europe | 9 April 2003 | 2,950 kg with propellants (1,350 kg dry mass) | 3100 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | [223] | |

| 20. | INSAT-3E | Ariane 5

V-162 |

Arianespace | Europe | 27 September 2003 | 2,778 kg with propellants (1,218 kg dry mass) | 3100 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | [224] | |

| 21. | INSAT-4A | Ariane 5

V169 |

Arianespace | Europe | 22 December 2005 | 3081 kg with propellants (1386.55 kg dry mass) | 5922 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | Communication satellite | [225] |

| 22. | INSAT-4B | Ariane 5 ECA | Arianespace | Europe | 12 March 2007 | 3,025 kg with propellants | 5859 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | Communication satellite | [226] |

| 23. | GSAT-8 | Ariane-5 VA-202 | Arianespace | Europe | 21 May 2011 | 3,093 kg with propellants (1,426 kg dry mass) | 6242 W | Geosynchronous | More than 12 years | Communication satellite | [227] |

| 24. | INSAT-3D | Ariane-5 VA-214 | Arianespace | Europe | 26 July 2013 | 2,061 kg with propellants (937.8 kg dry mass) | 1164 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | Weather satellite | [228] |

| 24. | GSAT-7 | Ariane-5 VA-215 | Arianespace | Europe | 30 August 2013 | 2,650 kg with propellants (1,211 kg dry mass) | 2915 W | Geosynchronous | 7 years | Communication satellite | [229] |

| 26. | GSAT-10 | Ariane-5 VA-209 | Arianespace | Europe | 29 September 2010 | 3,400 kg with propellants (1,498 kg dry mass) | 6474 W | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite | [230] |

| 27. | GSAT-16 | Ariane-5 VA-221 | Arianespace | Europe | 7 December 2014 | 3,181.6 kg with propellants | 6000 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | Communication satellite, carries 48 transponders, the most in any ISRO communication satellite so far. | [231] |

| 28. | GSAT-15 | Ariane-5 VA-227 | Arianespace | Europe | 11 November 2015 | 3,164 kg with propellants | 6000 W | Geosynchronous | 12 years | Communication satellite, carries 24 transponders. | [232] |

| 29. | GSAT-18 | Ariane-5 VA-231 | Arianespace | Europe | 6 October 2016 | 3,404 kg | 6474 W | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite, carries 48 transponders. | [233] |

| 30. | GSAT-17 | Ariane-5 VA-238 | Arianespace | Europe | 28 June 2017 | 3,477 kg | 6474 W | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite, carries 42 transponders. | [234] |

| 31. | GSAT-11 | Ariane-5 VA-246 | Arianespace | Europe | 5 December 2018 | 5,854 kg | 13.4 kW | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite | [235] |

| 32. | GSAT-31 | Ariane-5 VA-247 | Arianespace | Europe | 5 February 2019 | 2,536 kg | 4.7 kW | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite | [236][237][238] |

| 33. | GSAT-30 | Ariane-5 VA-251 | Arianespace | Europe | 16 January 2020 | 3,547 kg | 6 kW | Geosynchronous | 15 years | Communication satellite | [239][240] |

Statistics

Last updated: 4 December 2019 [241]

- Total number of foreign satellites launched by ISRO : 319 (33 countries)[242]

- Spacecraft missions: 117

- Launch missions: 77

- Student satellites: 10 [243]

- Re-entry missions: 2

Budget for Dept. of Space

Allotted Budget Department wise in %age (Year 2019-20) for ISRO.

Controversies

S-band spectrum scam

In India, electromagnetic spectrum, being a scarce resource for wireless communication, is auctioned by the Government of India to telecom companies for use. As an example of its value, in 2010, 20 MHz of 3G spectrum was auctioned for ₹677 billion (US$9.5 billion). This part of the spectrum is allocated for terrestrial communication (cell phones). However, in January 2005, Antrix Corporation (commercial arm of ISRO) signed an agreement with Devas Multimedia (a private company formed by former ISRO employees and venture capitalists from the US) for lease of S band transponders (amounting to 70 MHz of spectrum) on two ISRO satellites (GSAT 6 and GSAT 6A) for a price of ₹14 billion (US$200 million), to be paid over a period of 12 years. The spectrum used in these satellites (2500 MHz and above) is allocated by the International Telecommunication Union specifically for satellite-based communication in India. Hypothetically, if the spectrum allocation is changed for utilisation for terrestrial transmission and if this 70 MHz of spectrum were sold at the 2010 auction price of the 3G spectrum, its value would have been over ₹2,000 billion (US$28 billion). This was a hypothetical situation. However, the Comptroller and Auditor General of India considered this hypothetical situation and estimated the difference between the prices as a loss to the Indian Government.[244][245]

There were lapses on implementing Government of India procedures. Antrix/ISRO had allocated the capacity of the above two satellites to Devas Multimedia on an exclusive basis, while rules said it should always be non-exclusive. The Cabinet was misinformed in November 2005 that several service providers were interested in using satellite capacity, while the Devas deal was already signed. Also, the Space Commission was kept in the dark while taking approval for the second satellite (its cost was diluted so that Cabinet approval was not needed). ISRO committed to spending ₹7.66 billion (US$110 million) of public money on building, launching, and operating two satellites that were leased out for Devas.

In late 2009, some ISRO insiders exposed information about the Devas-Antrix deal,[245][246] and the ensuing investigations resulted in the deal being annulled. G. Madhavan Nair (ISRO Chairperson when the agreement was signed) was barred from holding any post under the Department of Space. Some former scientists were found guilty of "acts of commission" or "acts of omission". Devas and Deutsche Telekom demanded US$2 billion and US$1 billion, respectively, in damages.[247] Government of India's Department of Revenue and Ministry of Corporate Affairs initiated an inquiry into Devas shareholding.

The Central Bureau of Investigation concluded investigations into the Antrix-Devas scam and registered a case against the accused in the Antrix-Devas deal under Section 120-B, besides Section 420 of IPC and Section 13(2) read with 13(1)(d) of PC Act, 1988 on 18 March 2015 against the then Executive Director of Antrix Corporation, two officials of USA-based company, Bangalore based private multimedia company, and other unknown officials of Antrix Corporation or Department of Space.[248][249]

Devas Multimedia started arbitration proceedings against Antrix in June 2011. In September 2015, the International Court of Arbitration of the International Chamber of Commerce ruled in favour of Devas, and directed Antrix to pay US$672 million (Rs 44.35 billion) in damages to Devas.[250] Antrix opposed the Devas plea for tribunal award in the Delhi High Court.[251]

See also

- Comparison of Asian national space programs

- Deep Ocean mission

- Department of Space, administers the Indian space program

- Indian Institute of Space Science and Technology

- ISRO spinoffs technologies

- List of chairmen of the Indian Space Research Organisation

- List of foreign satellites launched by India

- List of government space agencies

- List of Indian satellites

- List of ISRO missions

- New Space India Limited

- Swami Vivekananda Planetarium

- Telecommunications in India

- Timeline of Solar System exploration

References

Citations

- "ISRO gets new identity". Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "A 'vibrant' new logo for ISRO". Times of India. 19 August 2002. Archived from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- "Chairman ISRO, Secretary DOS". Department of Space, Government of India. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Annual Report 2019-20, Department of Space" (PDF). 14 February 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 February 2020. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- "Department of Space Budget" (PDF). Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- "Vision and Mission Statements". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Pushpa M. Bhargava; Chandana Chakrabarti (2003). The Saga of Indian Science Since Independence: In a Nutshell. Universities Press. pp. 39–. ISBN 978-81-7371-435-1. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- Marco Aliberti (2018). India in Space: Between Utility and Geopolitics. Springer. pp. 12–. ISBN 978-3-319-71652-7.

- Roger D. Launius (2018). The Smithsonian History of Space Exploration: From the Ancient World to the Extraterrestrial Future. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 196–. ISBN 978-1-58834-637-7.

- Nambi Narayanan; Arun Ram (2018). Ready To Fire: How India and I Survived the ISRO Spy Case. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-93-86826-27-5.

- Brian Harvey; Henk H. F. Smid; Theo Pirard (2011). Emerging Space Powers: The New Space Programs of Asia, the Middle East and South-America. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 144–. ISBN 978-1-4419-0874-2.

- "Isro's golden jubilee: 50 years of space explorations". Archived from the original on 17 August 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Overview". From Fishing Hamlet To Red Planet. Harper Collins. 2015. p. 13. ISBN 978-9351776895. Archived from the original on 9 September 2017. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

The three men responsible for launching our country's space programme were: Dr.Homi Bhabha, the architect of India's nuclear project, Dr.Vikram Sarabhai, now universally acknowledged as the father of the Indian space programme and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India. All three came from rich and cultured families; each of them was determined to do his bit for the newly emerging India.

- "Government of India Atomic Energy Commission | Department of Atomic Energy". Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Department of Space and ISRO HQ - ISRO". Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- Eligar Sadeh (2013). Space Strategy in the 21st Century: Theory and Policy. Routledge. pp. 303–. ISBN 978-1-136-22623-6. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- "About ISRO - ISRO". Archived from the original on 28 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- "Aryabhata – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 15 August 2018.

- "GSLV-D5 – Indian cryogenic engine and stage" (PDF). Official ISRO website. Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "GSLV soars to space with Indian cryogenic engine". Spaceflight Now. 5 January 2014. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Water on the Moon – ISRO". www.isro.gov.in. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Thomas, Arun. "Mangalyan". CNN. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Pallav Bagla (22 June 2016). "India Launches Record 20 Satellites in 26 Minutes, Google Is A Customer". Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2016.

- "ISRO sends record 104 satellites in one go, becomes the first to do so". The Economic Times. Archived from the original on 15 February 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- Barry, Ellen (15 February 2017). "India Launches 104 Satellites From a Single Rocket, Ramping Up a Space Race". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 5 April 2017. Retrieved 15 February 2017.

- "About ISRO – Future Programme". Indian Space Research Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- "Transported on a bicycle, launched from a church: The fascinating story of India's first rocket launch". India Today. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- Daniel, 486.

- Daniel, 487

- Daniel, 488

- Daniel, 489

- "ISRO – Vision and Mission Statements". ISRO. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Burleson, 136

- "Dr. Vikram Ambalal Sarabhai (1963-1971) - ISRO". Archived from the original on 22 April 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "List of Important Speeches And Papers By Dr. Vikram A. Sarabhai" (PDF). PRL.res.in. p. 113. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.