IG Farben

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG (German for ''Dye industry syndicate corporation''), commonly known as IG Farben, was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, and Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler Ter Meer[1]—it was seized by the Allies after World War II and divided back into its constituent companies.[lower-alpha 1]

| |

IG Farben head office, Frankfurt, completed in 1931 and seized by the Allies in 1945 as the headquarters of the Supreme Allied Command. In 2001 it became part of the University of Frankfurt. | |

| Aktiengesellschaft | |

| ISIN | DE0005759070 |

| Industry | Chemicals |

| Fate | Liquidated |

| Predecessors | BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, Griesheim-Elektron, Weiler Ter Meer[1] |

| Successors | Agfa, BASF, Bayer, Hoechst (now Sanofi) |

| Founded | 2 December 1925 |

| Defunct | 1952 (liquidation started) 31 October 2012 (liquidation accomplished) |

| Headquarters | Frankfurt am Main |

Key people | Carl Bosch, Carl Duisberg, Hermann Schmitz, Edmund ter Meer, Arthur von Weinberg |

Number of employees | 330,000 in 1943, including slave labour[2] |

In its heyday, IG Farben was the largest company in Europe and the largest chemical and pharmaceutical company in the world.[4] IG Farben scientists made fundamental contributions to all areas of chemistry and the pharmaceutical industry. Otto Bayer discovered the polyaddition for the synthesis of polyurethane in 1937,[5] and three company scientists became Nobel laureates: Carl Bosch and Friedrich Bergius in 1931 "for their contributions to the invention and development of chemical high pressure methods",[6] and Gerhard Domagk in 1939 "for the discovery of the antibacterial effects of prontosil".[7]

The company had ties in the 1920s to the liberal German People's Party and was accused by the Nazis of being an "international capitalist Jewish company".[8] A decade later, it was a Nazi Party donor and, after the Nazi takeover of Germany in 1933, a major government contractor, providing significant material for the German war effort. Throughout that decade it purged itself of its Jewish employees; the remainder left in 1938.[9] Described as "the most notorious German industrial concern during the Third Reich",[10] IG Farben relied in the 1940s on slave labour from concentration camps, including 30,000 from Auschwitz.[11] One of its subsidiaries supplied the poison gas, Zyklon B, that killed over one million people in gas chambers during the Holocaust.[lower-alpha 2][13]

The Allies seized the company at the end of the war in 1945[lower-alpha 1] and the US authorities put its directors on trial. Held from 1947 to 1948 as one of the subsequent Nuremberg trials, the IG Farben trial saw 23 IG Farben directors tried for war crimes and 13 convicted.[14] By 1951 all had been released by the American high commissioner for Germany, John J. McCloy.[15] What remained of IG Farben in the West was split in 1951 into its six constituent companies, then again into three: BASF, Bayer and Hoechst.[lower-alpha 1] These companies continued to operate as an informal cartel and played a major role in the West German Wirtschaftswunder. Following several later mergers the main successor companies are Agfa, BASF, Bayer and Sanofi. In 2004 the University of Frankfurt, housed in the former IG Farben head office, set up a permanent exhibition on campus, the Norbert Wollheim memorial, for the slave labourers and those killed by Zyklon B.[16]

Early history

Background

At the beginning of the 20th century, the German chemical industry dominated the world market for synthetic dyes. Three major firms BASF, Bayer and Hoechst, produced several hundred different dyes. Five smaller firms, Agfa, Cassella, Chemische Fabrik Kalle, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron and Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler-ter Meer, concentrated on high-quality specialty dyes. In 1913 these eight firms produced almost 90 percent of the world supply of dyestuffs and sold about 80 percent of their production abroad.[17] The three major firms had also integrated upstream into the production of essential raw materials, and they began to expand into other areas of chemistry such as pharmaceuticals, photographic film, agricultural chemicals and electrochemicals. Contrary to other industries, the founders and their families had little influence on the top-level decision-making of the leading German chemical firms, which was in the hands of professional salaried managers.[18] Because of this unique situation, the economic historian Alfred Chandler called the German dye companies "the world's first truly managerial industrial enterprises".[19]

With the world market for synthetic dyes and other chemical products dominated by the German industry, German firms competed vigorously for market shares. Although cartels were attempted, they lasted at most for a few years. Others argued for the formation of a profit pool or Interessen-Gemeinschaft (abbr. IG, lit. "community of interest").[21] In contrast, the chairman of Bayer, Carl Duisberg, argued for a merger. During a trip to the United States in the spring of 1903, he had visited several of the large American trusts such as Standard Oil, U.S. Steel, International Paper and Alcoa.[22] In 1904, after returning to Germany, he proposed a nationwide merger of the producers of dye and pharmaceuticals in a memorandum to Gustav von Brüning, the senior manager at Hoechst.[23]

Hoechst and several pharmaceutical firms refused to join. Instead, Hoechst and Cassella made an alliance based on mutual equity stakes in 1904. This prompted Duisberg and Heinrich von Brunck, chairman of BASF, to accelerate their negotiations. In October 1904 an Interessen-Gemeinschaft between Bayer, BASF and Agfa was formed, also known as the Dreibund or little IG. Profits of the three firms were pooled, with BASF and Bayer getting 43 percent and Agfa 14 percent of all profits.[24] The two alliances were loosely connected with each other through an agreement between BASF and Hoechst to jointly exploit the patent on the Heumann-Pfleger indigo synthesis.[25]

Within the Dreibund, Bayer and BASF concentrated on dye, while Agfa increasingly concentrated on photographic film. Although there was some cooperation between the technical staff in production and accounting, there was little cooperation between the firms in other areas. Neither were production or distribution facilities consolidated nor did the commercial staff cooperate. In 1908 Hoechst and Cassella acquired 88 percent of the shares of Chemische Fabrik Kalle. As Hoechst, Cassella and Kalle were connected by mutual equity shares and were located close to each other in the Frankfurt area, this allowed them to cooperate more successfully than the Dreibund, although they also did not rationalize or consolidate their production facilities.[26]

Foundation

IG Farben was founded in December 1925 as a merger of six companies: BASF (27.4 percent of equity capital); Bayer (27.4 percent); Hoechst, including Cassella and Chemische Fabrik Kalle (27.4 percent); Agfa (9 percent); Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron (6.9 percent); and Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler Ter Meer (1.9 percent).[1] The supervisory board members became widely known as, and were said to call themselves jokingly, the "Council of Gods" (Rat der Götter).[27] The designation was used as the title of an East German film, The Council of the Gods (1950).

In 1926 IG Farben had a market capitalization of 1.4 billion Reichsmark (equivalent to 5 billion 2009 euros) and a workforce of 100,000, of which 2.6 percent were university educated, 18.2 percent were salaried professionals and 79.2 percent were workers.[1] BASF was the nominal survivor; all shares were exchanged for BASF shares. Similar mergers took place in other countries. In the United Kingdom Brunner Mond, Nobel Industries, United Alkali Company and British Dyestuffs merged to form Imperial Chemical Industries in September 1926. In France Établissements Poulenc Frères and Société Chimique des Usines du Rhône merged to form Rhône-Poulenc in 1928.[28] The IG Farben Building, headquarters for the conglomerate in Frankfurt am Main, Germany, was completed in 1931. In 1938 the company had 218,090 employees.[29]

IG Farben was controversial on both the far left and far right, partly for the same reasons, related to the size and international nature of the conglomerate and the Jewish background of several of its key leaders and major shareholders. Far-right newspapers of the 1920s and early 1930s accused it of being an "international capitalist Jewish company". The liberal and business-friendly German People's Party was its most pronounced supporter. Not a single member of the management of IG Farben before 1933 supported the Nazi Party; four members, or a third, of the IG Farben supervisory board were themselves Jewish.[8] The company ended up being the "largest single contribution" to the successful Nazi election campaign of 1933;[30] there is also evidence of "secret contributions" to the party in 1931 and 1932.[31]

Throughout the 1930s the company underwent a process of Aryanization, and by 1938 Jewish employees had been dismissed and the Jews on the board had resigned. The remaining few left in 1938 after Hermann Göring issued a decree, as part of the Nazis' Four Year Plan (announced in 1936), that the German government would make foreign exchange available to German firms to fund construction or purchases overseas only if certain conditions were met, which included making sure the company employed no Jews.[9]

Products

IG Farben's products included synthetic dyes, nitrile rubber, polyurethane, prontosil, and chloroquine. The nerve agent Sarin was first discovered by IG Farben.[32] The company is perhaps best known for its role in producing the poison gas Zyklon B. One product crucial to the operations of the Wehrmacht was synthetic fuel, made from lignite using the coal liquefaction process.

IG Farben scientists made fundamental contributions to all areas of chemistry. Otto Bayer discovered the polyaddition for the synthesis of polyurethane in 1937.[5] Several IG Farben scientists were awarded a Nobel Prize. Carl Bosch and Friedrich Bergius were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1931 "in recognition of their contributions to the invention and development of chemical high pressure methods".[6] Gerhard Domagk was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1939 "for the discovery of the antibacterial effects of prontosil".[7]

World War II and the Holocaust

Growth and slave labour

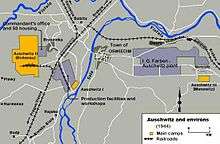

IG Farben has been described as "the most notorious German industrial concern during the Third Reich".[10] When World War II began, it was the fourth largest corporation in the world and the largest in Europe.[33] In February 1941 Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler signed an order[34] supporting the construction of an IG Farben Buna-N (synthetic rubber) plant—known as Monowitz Buna Werke (or Buna)—near the Monowitz concentration camp, part of the Auschwitz concentration camp complex in German-occupied Poland. (Monowitz came to be known as Auschwitz III; Auschwitz I was the administrative centre and Auschwitz II-Birkenau the extermination camp.) The IG Farben plant's workforce consisted of slave labour from Auschwitz, leased to the company by the SS for a low daily rate.[35] One of IG Farben's subsidiaries supplied the poison gas, Zyklon B, that killed over one million people in gas chambers.[36]

Company executives said after the war that they had not known what was happening inside the camps. According to the historian Peter Hayes, "the killings were an open secret within Farben, and people worked at not reflecting upon what they knew."[37]

In 1978 Joseph Borkin, who investigated the company as a United States Justice Department lawyer, quoted an American report: "Without I.G.'s immense productive facilities, its far-reaching research, varied technical expertise and overall concentration of economic power, Germany would not have been in a position to start its aggressive war in September 1939."[38] The company placed its resources, technical capabilities and overseas contacts at the German government's disposal. The minutes of a meeting of the Commercial Committee on 10 September 1937 noted:

It is generally agreed that under no circumstances should anybody be assigned to our agencies abroad who is not a member of the German Labor Front and whose positive attitude towards the new era has not been established beyond any doubt. Gentlemen who are sent abroad should be made to realize that it is their special duty to represent National Socialist Germany. ... The Sales Combines are also requested to see to it that their agents are adequately supplied with National Socialist literature.[39]

This message was repeated by Wilhelm Rudolf Mann, who chaired a meeting of the Bayer division board of directors on 16 February 1938, and who in an earlier meeting had referred to the "miracle of the birth of the German nation": "The chairman points out our incontestable being in line with the National Socialist attitude in the association of the entire 'Bayer' pharmaceutica and insecticides; beyond that, he requests the heads of the offices abroad to regard it as their self-evident duty to collaborate in a fine and understanding manner with the functionaries of the Party, with the DAF (German Workers' Front), et cetera. Orders to that effect again are to be given to the leading German gentlemen so that there may be no misunderstanding in their execution."[40]

By 1943 IG Farben was manufacturing products worth three billion marks in 334 facilities in occupied Europe; almost half its workforce of 330,000 men and women consisted of slave labour or conscripts, including 30,000 Auschwitz prisoners. Altogether its annual net profit was around RM 0.5 billion (equivalent to 2 billion 2009 euros).[2] In 1945, according to Raymond G. Stokes, it manufactured all the synthetic rubber and methanol in Germany, 90 percent of its plastic and "organic intermediates", 84 percent of its explosives, 75 percent of its nitrogen and solvents, around 50 percent of its pharmaceuticals, and around 33 percent of its synthetic fuel.[41]

Medical experiments

Staff of the Bayer group at IG Farben conducted medical experiments on concentration-camp inmates at Auschwitz and at the Mauthausen concentration camp.[42][43] At Auschwitz they were led by Bayer employee Helmuth Vetter, an Auschwitz camp physician and SS captain, and Auschwitz physicians Friedrich Entress and Eduard Wirths. Most of the experiments were conducted in Birkenau in Block 20, the women's camp hospital. The patients were suffering from, and in many cases had been deliberately infected with, typhoid, tuberculosis, diphtheria and other diseases, then were given preparations named Rutenol, Periston, B-1012, B-1034, B-1036, 3582 and P-111. According to prisoner-physicians who witnessed the experiments, after being given the drugs the women would experience circulation problems, bloody vomiting, and painful diarrhea "containing fragments of muscus membrane". Of the 50 typhoid sufferers given 3852, 15 died; 40 of the 75 tuberculosis patients given Rutenol died.[44]

For one experiment, which tested an anaesthetic, Bayer had 150 women sent from Auschwitz to its own facility. They paid RM 150 per woman, all of whom died as a result of the research; the camp had asked for RM 200 per person, but Bayer had said that was too high.[45] A Bayer employee wrote to Rudolf Höss, the Auschwitz commandant: "The transport of 150 women arrived in good condition. However, we were unable to obtain conclusive results because they died during the experiments. We would kindly request that you send us another group of women to the same number and at the same price."[46]

Zyklon B

Between 1942 and 1945 a cyanide-based pesticide, Zyklon B, was used to kill over one million people, mostly Jews, in gas chambers in Europe, including in the Auschwitz II and Majdanek extermination camps in occupied Poland.[47] The poison gas was supplied by an IG Farben subsidiary, Degesch (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schädlingsbekämpfung MbH, or German Company for Pest Control).[36] Degesch originally supplied the gas to Auschwitz to fumigate clothing that was infested with lice, which carried typhus. Fumigation took place within a closed room, but it was a slow process, so Degesch recommended building small gas chambers, which heated the gas to over 30 °C and killed the lice within one hour. The idea was that the inmates would be shaved and showered while their clothes were being fumigated.[48] The gas was first used on human beings in Auschwitz (650 Soviet POWs and 200 others) in September 1941.[49]

Peter Hayes (Industry and Ideology: I. G. Farben in the Nazi Era, 2001) compiled the following table showing the increase in Zyklon B ordered by Auschwitz (figures with an asterisk are incomplete). One ton of Zyklon B was enough to kill around 312,500 people.[50]

| 1938 | 1939 | 1940 | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sales (thousands of marks) | 257 | 337 | 448 | 366 | 506 | 544 | |

| Percentage of total Degesch earnings | 30 | 38 | 57 | 48 | 39 | 52 | |

| Production (short tons) | 160 | 180 | 242 | 194 | 321 | 411 | 231 |

| Volume ordered by Auschwitz (short tons) | 8.2 | 13.4 | 2.2* | ||||

| Percentage of production ordered by Auschwitz | 2.5 | 3.3 | 1.0* | ||||

| Volume ordered by Mauthausen (not an extermination camp) | 0.9 | 1.5 |

Several IG Farben executives said after the war that they did not know about the gassings, despite the increase in sales of Zyklon B to Auschwitz. IG Farben owned 42.5 percent of Degesch shares, and three members of Degesch's 11-person executive board, Wilhelm Rudolf Mann, Heinrich Hörlein and Carl Wurster, were directors of IG Farben.[51] Mann, who had been an SA-Sturmführer,[52] was the chair of Degesch's board. Peter Hayes writes that the board did not meet after 1940, and that although Mann "continued to review the monthly sales figures for Degesch, he could not necessarily have inferred from them the uses to which the Auschwitz camp was putting the product".[12] IG Farben executives did visit Auschwitz but not Auschwitz II-Birkenau, where the gas chambers were located.[53]

Other IG Farben staff appear to have known. Ernst Struss, secretary of the IG Farben's managing board, testified after the war that the company's chief engineer at Auschwitz had told him about the gassings.[54] The general manager of Degesch is said to have learned about the gassings from Kurt Gerstein of the SS.[53] According to the post-war testimony of Rudolf Höss, the Auschwitz commandant, he was asked by Walter Dürrfeld, technical manager of the IG Farben Auschwitz plant, whether it was true that Jews were being cremated at Auschwitz. Höss replied that he could not discuss it and thereafter assumed that Dürrfeld knew.[55] Dürrfeld, a friend of Höss, denied knowing about it.[56]

Hayes writes that the inmates of Auschwitz III, which supplied the slave labour for IG Farben, were well aware of the gas chambers, in part because of the stench from the Auschwitz II crematoria, and in part because IG Farben supervisors in the camp spoke about the gassings, including using the threat of them to make the inmates work harder.[57] Charles Coward, a British POW who had been held at Auschwitz III, told the IG Farben trial:

The population at Auschwitz was fully aware that people were being gassed and burned. On one occasion they complained about the stench of the burning bodies. Of course all of the Farben people knew what was going on. Nobody could live in Auschwitz and work in the plant, or even come down to the plant, without knowing what was common knowledge to everybody.[58]

Mann, Hörlein and Wuster (directors of both IG Farben and Degesch) were acquitted at the IG Farben trial in 1948 of having supplied Zyklon B for the purpose of mass extermination. The judges ruled that the prosecution had not shown that the defendants or executive board "had any persuasive influence on the management policies of Degesch or any significant knowledge as to the uses to which its production was being put".[51] In 1949 Mann became head of pharmaceutical sales at Bayer.[52] Hörlein became chair of Bayer's supervisory board.[59] Wurster became chair of the IG Farben board, helped to reestablish BASF as a separate company, and became an honorary professor at the University of Heidelberg.[60] Dürrfeld was sentenced to eight years, then pardoned in 1951 by John McCloy, the American high commissioner for Germany, after which he joined the management or supervisory boards of several chemical companies.[56]

Seizure by the Allies

The company destroyed most of its records as it became clear that Germany was losing the war. In September 1944 Fritz ter Meer, a member of IG Farben's supervisory board and future chair of Bayer's board of directors, and Ernst Struss, secretary of the company's managing board, are said to have made plans to destroy company files in Frankfurt in the event of an American invasion.[61] As the Red Army approached Auschwitz in January 1945 to liberate it, IG Farben reportedly destroyed the company's records inside the camp,[62] and in the spring of 1945, the company burned and shredded 15 tons of paperwork in Frankfurt.[61]

The Americans seized the company's property under "General Order No. 2 pursuant to Military Government Law No. 52", 2 July 1945, which allowed the US to disperse "ownership and control of such of the plants and equipment seized under this order as have not been transferred or destroyed". The French followed suit in the areas they controlled.[63] On 30 November 1945 Allied Control Council Law No. 9, "Seizure of Property owned by I.G. Farbenindustrie and the Control Thereof", formalized the seizure for "knowingly and prominently ... building up and maintaining German war potential".[64][2] The division of property followed the division of Germany into four zones: American, British, French and Soviet.[63]

In the Western occupation zone, the idea of destroying the company was abandoned as the policy of denazification evolved,[10] in part because of a need for industry to support reconstruction, and in part because of the company's entanglement with American companies, notably the successors of Standard Oil. In 1951 the company was split into its original constituent companies. The four largest quickly bought the smaller ones. In January 1955 the Allied High Commission issued the I.G. Liquidation Conclusion Law,[65] naming IG Farben's legal successor as IG Farbenindustrie AG in Abwicklung (IGiA)[66] ("I.G. Farbenindustrie AG in Liquidation).[65]

IG Farben trial

In 1947 the American government put IG Farben's directors on trial. The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al. (1947–1948), also known as the IG Farben trial, was the sixth of 12 trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) against leading industrialists of Nazi Germany. There were five counts against the IG Farben directors:

- "the planning, preparation, initiation, and waging of wars of aggression and invasions of other countries;

- "committing war crimes and crimes against humanity through the plunder and spoliation of public and private property in countries and territories that came under German occupation;

- "committing war crimes and crimes against humanity through participating in the enslavement and deportation for slave labor of civilians from German-occupied territories and of German nationals;

- "participation by defendants Christian Schneider, Heinrich Buetefisch, and Erich von der Heyde in the SS, a recently-declared criminal organization; and

- "participation in a common plan or conspiracy to commit crimes against peace".[67][14]

Of the 24 defendants arraigned, one fell ill and his case was discontinued. The indictment was filed on 3 May 1947; the trial lasted from 27 August 1947 until 30 July 1948. The judges were Curtis Grover Shake (presiding), James Morris, Paul M. Hebert, and Clarence F. Merrell as an alternate judge. Telford Taylor was the chief counsel for the prosecution. Thirteen defendants were found guilty,[67] with sentences ranging from 18 months to eight years.[68] All were cleared of the first count of waging war.[67] The heaviest sentences went to those involved with Auschwitz,[68] which was IG Farben's Upper Rhine group.[69] Ambros, Bütefisch, Dürrfeld, Krauch and ter Meer were convicted of "participating in ... enslavement and deportation for slave labor".[70]

All defendants who were sentenced to prison received early release. Most were quickly restored to their directorships and other positions in post-war companies, and some were awarded the Federal Cross of Merit.[71] Those who served prison sentences included:

| Director | IG Farben position | Sentence (years) | Post-sentence | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carl Krauch | Chair of the supervisory board, member of Göring's Office of the Four-Year Plan | Six[70] | Joined supervisory board of the Bunawerke Hüls GmbH | |

| Hermann Schmitz | CEO, Reichstag member | Four[70] | Board member, Deutsche Bank in Berlin; Honorary chair, Rheinische Stahlwerke AG board | [72][14] |

| Fritz ter Meer | Supervisory board member | Seven[70] | Chair, Bayer AG board; board member of several firms | [73][14] |

| Otto Ambros | Supervisory board member, manager of IG Farben Auschwitz | Eight[70] | Board member of Chemie Grünenthal (active during the thalidomide scandal), Feldmühle, and Telefunken; economic consultant in Mannheim | [74][14] |

| Heinrich Bütefisch | Supervisory board member, head of fuel sector at IG Farben Auschwitz | Six[70] | Board member for Deutsche Gasolin AG, Feldmühle, and Papier- und Zellstoffwerke AG; consultant and board member for Ruhrchemie AG Oberhausen | [75][14] |

| Walter Dürrfeld | Technical manager of IG Farben Auschwitz | Eight[70] | [56] | |

| Georg von Schnitzler | Chair, Chemical Committee | Five[70] | President, Deutsch-Ibero-Amerikanische Gesellschaft | [76][14] |

| Max Ilgner | Supervisory board member | Three[70] | Chair of the board of a chemistry firm in Zug | [77][14] |

| Heinrich Oster | Alternate board member; BASF board member | Two[70] | Gelsenberg AG board member | [78][14] |

Those acquitted included:

| Director | IG Farben position | Outcome | Post-sentence | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carl Wurster | Board member, head of IG Farben's Upper Rhine Business Group | Acquitted | IG Farben board chair and led the reestablishment of BASF. After retiring joined or chaired supervisory boards in Bosch, Degussa and Allianz. | [60] |

| Fritz Gajewski | Board member, manager of Agfa division | Acquitted | Chair of the board of Dynamit Nobel | [79] |

| Christian Schneider | Acquitted | Joined supervisory boards of Süddeutsche Kalkstickstoff-Werke AG Trostberg and Rheinauer Holzhydrolyse-GmbH, Mannheim. | [80] | |

| Hans Kühne | Acquitted | Took a position at Bayer, Elberfeld | [81] | |

| Carl Lautenschläger | Acquitted | Research associate at Bayer, Elberfeld | [82] | |

| Wilhelm Rudolf Mann | Head of pharmaceutical sales for the Bayer division of IG Farben, member of the Sturmabteilung | Acquitted | Resumed his position at Bayer. Also presided over the GfK (Society for Consumer Research) and the Foreign Trade Committee of the BDI, Federation of German Industry. | [83] |

| Heinrich Gattineau | Acquitted | Joined the board and supervisory council of WASAG Chemie-AG and Mitteldeutsche Sprengstoff-Werke GmbH. | [84] |

Liquidation

Agfa, BASF and Bayer remained in business; Hoechst spun off its chemical business in 1999 as Celanese AG before merging with Rhône-Poulenc to form Aventis, which later merged with Sanofi-Synthélabo to form Sanofi. Two years earlier, another part of Hoechst was sold in 1997 to the chemical spin-off of Sandoz, the Muttenz (Switzerland) based Clariant. The successor companies remain some of the world's largest chemical and pharmaceutical companies.

Although IG Farben was officially put into liquidation in 1952, this did not end the company's legal existence. The purpose of a corporation's continuing existence, being "in liquidation", is to ensure an orderly wind-down of its affairs. As almost all its assets and all its activities had been transferred to the original constituent companies, IG Farben was from 1952 largely a shell company with no real activity.

In 2001 IG Farben announced that it would formally wind up its affairs in 2003. It had been continually criticized over the years for failing to pay compensation to the former labourers; its stated reason for its continued existence after 1952 was to administer its claims and pay its debts. The company, in turn, blamed ongoing legal disputes with the former captive labourers for its inability to be legally dissolved and have the remaining assets distributed as reparations.[85]

On 10 November 2003 its liquidators filed for insolvency,[86] but this did not affect the existence of the company as a legal entity. While it did not join a national compensation fund set up in 2001 to pay the victims, it contributed 500,000 DM (£160,000 or €255,646) towards a foundation for former captive labourers under the Nazi regime. The remaining property, worth DM 21 million (£6.7 million or €10.7 million), went to a buyer.[87] Each year, the company's annual meeting in Frankfurt was the site of demonstrations by hundreds of protesters.[85] Its stock (denominated in Reichsmarks) traded on German markets until early 2012. As of 2012 it still existed as a corporation in liquidation.[88]

IG Farben in media

Film and television

- IG Farben is the company said to be supporting German terror activities and research of uranium ores in Brazil after World War II in Alfred Hitchcock's film noir Notorious (1946).

- The Council of the Gods (1951), produced by (DEFA director Kurt Maetzig), is an East German film about IG Farben's role in World War II and the subsequent trial.

- IG Farben is the name of the arms dealer played by Dennis Hopper in the 1987 independent film Straight to Hell.[89]

- In Foyle's War series eight, episode 1 ("High Castle"), Foyle tours Monowitz as part of his investigation of the murder of a London University professor, who as a translator for the Nuremberg Trials becomes involved with an American industrialist who owns a petroleum company, and a German war criminal named Linz, who also turns up dead, in his cell. Linz's firm, IG Farben, had hired from the SS forced laborers incarcerated at Monowitz.

Literature

- IG Farben plays a prominent role in Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow, primarily as the manufacturer of the elusive and mysterious plastic product "Imipolex G."

- The company also plays a prominent role in Philip K. Dick's alternative history novel The Man in the High Castle.

- IG Farben is the German consortium that buys Du Pont in the Kurt Vonnegut novel Hocus Pocus.

Games

- In the Hearts of Iron series by "Paradox Interactive", IG Farben is one of several Design Companies that may be selected to provides a bonus to technology research for Germany; other options include Siemens and Krupp.[90]

See also

- American IG

- Bernard Bernstein

- Interhandel (I.G. Chemie)

- Nuremberg Trials bibliography

- Pope John Paul II born Karol Józef Wojtyła

Sources

Notes

- Peter Hayes (2001): "[O]ne of the first acts of the American occupation authorities in 1945 was to seize the enterprise as punishment for 'knowingly and prominently ... building up and maintaining German war potential'. Two years later, twenty-three of the firm's principal officers went on trial ... By the time John McCloy, the American high commissioner [for Germany], pardoned the last of them in 1951, IG Farben scarcely existed. Its holdings in the German Democratic Republic had been nationalized; those in the Federal Republic had been divided into six, later chiefly three, separate corporations: BASF, Bayer, and Hoechst."[3] Also see "Law No. 9" (PDF). Allied Control Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2018.

- Peter Hayes (2001): "[I]t was Zyklon B, a granular vaporizing pesticide, that asphyxiated the Jews of Auschwitz, and a subsidiary of IG, the Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Schädlingsbekämpfung MbH (German Vermin-Combating Corporation), or Degesch, that controlled the manufacture and distribution of the Zyklon. IG's 42.5 percent of the stock in Degesch translated into three seats on its Administrative Committee, occupied by members of Farben's own Vorstand [board of directors], Heinrich Hoerlein, Carl Wurster, and Wilhelm R. Mann, who acted as chairman. But this body ceased to meet after 1940. Though Mann continued to review the monthly sales figures for Degesch, he could not necessarily have inferred from them the uses to which the Auschwitz camp was putting the product ..."[12]

- Standing, left to right: Arthur von Weinberg, Carl Müller, Edmund ter Meer, Adolf Haeuser, Franz Oppenheim. Seated: Theodor Plieninger, Ernst von Simson, Carl Bosch, Walther vom Rath, Wilhelm Kalle, Carl von Weinberg and Carl Duisberg

References

- Tammen 1978, p. 195

- Hayes 2001, pp. xxi–xxii.

- Hayes 2001, p. xxii.

- Hager 2006, p. 74.

- Nicholson 2006, p. 61.

- "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1931". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 27 October 2008.; "Carl Bosch". Nobel Foundation. "Carl Bosch (1874–1940)". Wollheim Memorial. Archived from the original on 9 October 2016.

- "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1939". Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 27 October 2008.; "Gerhard Domagk". Nobel Foundation.

- Bäumler 1988, p. 277ff.

- Hayes 2001, p. 196.

- Spicka 2018, p. 233.

- Hayes 2001, pp. xxi–xxii; Dickerman 2017, p. 440.

- Hayes 2001, p. 361.

- Bartrop 2017, pp. 742–743; Neumann 2012, p. 115.

- United Nations War Crimes Commission 1949.

- Schwartz 2001, p. 439; Finder, Joseph (12 April 1992). "Ultimate Insider, Ultimate Outsider". The New York Times.

- "Norbert Wollheim Memorial". Goethe Universität Frankfurt. Archived from the original on 24 September 2018. "IG Farben-Haus, Geschichte und Gegenwart" (in German). Fritz Bauer Institute. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007.

- Aftalion & Benfey 1991, p. 104; Chandler 2004, p. 475

- Chandler 2004, pp. 474–485.

- Chandler 2004, p. 481.

- Beer 1981, pp. 124–125.

- Chandler 2004, p. 479

- Beer 1981, pp. 124–125

- Duisberg 1923.

- Beer 1981, pp. 125–134

- Tammen 1978, p. 11

- Chandler 2004, p. 480.

- Kaiser, Arvid (16 August 2015). "Die Weltmarktführer von gestern", manager magazin.

- Aftalion & Benfey 1991, pp. 140, 143

- Fiedler 1999, p. 49.

- Borkin 1978, p. 71.

- Sasuly 1947, p. 66.

- Evans 2008, p. 669.

- van Pelt & Dwork 1996, p. 198.

- Schmaltz 2018, p. 215.

- Dickerman 2017, p. 440.

- Bartrop 2017, pp. 742–743.

- Hayes 2003, p. 346.

- Borkin 1978, p. 1; for more on Borkin, Pearson, Richard (6 July 1979). "Joseph Borkin, Antitrust Lawyer, Author Dies". The Washington Post.

- IG Farben trial, pp. 1281–1282.

- IG Farben trial, p. 1282.

- Stokes 1994, p. 70.

- Lifton & Hackett 1998, p. 310.

- "Other doctor-perpetrators". Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016.

- Strzelecka 2000, p. 362.

- Strzelecka 2000, p. 363; Rees 2006, p. 179; Jacobs 2017, pp. 312–314.Worthington, Daryl (20 May 2015). "IG Farben Opens Factory at Auschwitz". New Historian. Archived from the original on 22 May 2015.

- Strzelecka 2000, p. 363, citing Sehn, Jan (1957). Konzentrationslager Oswiecim-Brzezinka: Auf Grund von Dokumentation und Beweisquellen. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Prawnicze, p. 89ff; also see Rees 2006, p. 179; for Höss, Jeffreys 2008, p. 278.

- Neumann 2012, p. 115.

- van Pelt & Dwork 1996, pp. 219–221.

- Hilberg 1998, p. 84; also see Hayes 2001, p. 362.

- Hayes 2001, p. 362.

- United Nations War Crimes Commission 1949, p. 24.

- "Wilhelm Rudolf Mann (1894–1992)". Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institute. Archived from the original on 26 January 2012.

- Hayes 2001, p. 363.

- Maguire 2010, p. 146.

- Hayes 2001, p. 364.

- "Walther Dürrfeld (1899–1967)". Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institute. Archived from the original on 25 March 2016.

- Hayes 2001, p. 364; also see Benedikt Kautsky, hearing of witness, 29 January 1953. Hessisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Wiesbaden (HHStAW), Sec. 460, No. 1424 (Wollheim v. I.G. Farben), Vol. II, pp. 257–264.

- IG Farben trial, p. 606; Borkin 1978, p. 144; Maguire 2010, p. 146.

- "Philipp Heinrich Hörlein (1882–1954)". Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institute. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018.

- "Carl Wurster (1900–1974)". Wollheim Memorial, Fritz Bauer Institute. Archived from the original on 31 August 2018.

- Borkin 1978, p. 134.

- Borkin 1978, p. 134; Hilberg 2003, p. 1049.

- Abelshauser et al. 2003, p. 337.

- "Law No. 9" (PDF). Allied Control Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 September 2018. "Kontrollratsgesetz Nr. 9". Verfassungen der Welt. www.verfassungen.de. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017.

- "I.G. Farben in Liquidation from the 1950s to 1990". Wollheim Memorial. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017.

- Abelshauser et al. 2003, p. 335.

- "Subsequent Nuremberg Proceedings, Case #6, The IG Farben Case". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018.

- Abelshauser et al. 2003, p. 339.

- Abelshauser et al. 2003, p. 340.

- United States of America v Carl Krauch et al., p. 7.

- Jeffreys 2008, pp. 321–341.

- "Hermann Schmitz (1881–1960)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Fritz (Friedrich Hermann) ter Meer (1884–1967)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Otto Ambros (1901–1990)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Heinrich Bütefisch (1894–1969)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Georg von Schnitzler (1884–1962)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Max Ilgner (1899–1966)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Heinrich Oster (1878–1954)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Friedrich (Fritz) Gajewski (1885–1965)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Christian Schneider (1887–1972)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Hans Kühne (1880–1969)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Carl-Ludwig Lautenschläger (1888–1962)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Wilhelm Rudolf Mann (1894–1992)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Heinrich Gattineau (1905–1985)". Wollheim Memorial. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "IG Farben to be dissolved", BBC News, 17 September 2001.

- "Ehemalige Zwangsarbeiter gehen leer aus". Der Spiegel. 10 November 2003.

- Charles, Jonathan (10 November 2003). "Former Zyklon-B maker goes bust", BBC News.

- Marek, Michael (20 November 2012). "Norbert Wollheim gegen IG Farben". Deutsche Welle.

- Carr, Jay. "'Straight to Hell' Bypasses Substance," The Boston Globe, Wednesday, July 1, 1987. Retrieved February 4, 2020

- "List of design companies". HOI4 Wiki. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

Works cited

- Abelshauser, Werner; von Hippel, Wolfgang; Johnson, Jeffrey Allan; Stokes, Raymond G. (2003). German Industry and Global Enterprise. BASF: The History of a Company. New York: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Aftalion, Fred; Benfey, Otto Theodor (1991). A History of the International Chemical Industry. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-8207-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bartrop, Paul R. (2017). "Zyklon B". In Bartrop, Paul R.; Dickerman, Michael (eds.). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Volume 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 742–743.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bäumler, Ernst (1988). Die Rotfabriker: Familiengeschichte eines Weltunternehmens (Hoechst) (in German). Munich and Zürich: Piper. ISBN 978-3-492-10669-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beer, John Joseph (1981). The Emergence of the German Dye Industry. Manchester, NH: Ayer Company Publishers. ISBN 978-0-405-13835-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Borkin, Joseph (1978). The Crime and Punishment of IG Farben. New York, London: The Free Press, division of Macmillan Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-02-904630-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chandler, Alfred DuPont (2004). Scale and Scope: The Dynamics of Industrial Capitalism. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-78995-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dickerman, Michael (2017). "Monowitz". In Bartrop, Paul R.; Dickerman, Michael (eds.). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Volume 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 439–440.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Duisberg, Carl (1923) [1904]. "Denkschrift über die Vereinigung der deutschen Farbenfabriken". Abhandlungen, Vorträge und Reden aus den Jahren 1882–1921. Berlin. pp. 343–369.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- van Pelt, Robert Jan; Dwork, Deborah (1996). Auschwitz, 1270 to the Present. New York and London: W.W. Norton and Company.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Evans, Richard J. (2008). The Third Reich at War. London: Penguin.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fiedler, Martin (1999). "Die 100 größten Unternehmen in Deutschland – nach der Zahl ihrer Beschäftigten – 1907, 1938, 1973 und 1995". Zeitschrift für Unternehmensgeschichte (in German). 44 (1): 32–66. doi:10.1515/zug-1999-0104.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hager, Thomas (2006). The Demon under the Microscope. New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-1-4000-8214-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, Peter (2001) [1987]. Industry and Ideology: IG Farben in the Nazi Era. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hayes, Peter (Fall 2003). "Auschwitz, Capital of the Holocaust". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 17 (2): 330–350. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcg005.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hilberg, Raul (2003) [1961]. The Destruction of the European Jews. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hilberg, Raul (1998) [1994]. "Auschwitz and the Final Solution". In Berenbaum, Michael; Gutman, Yisrael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 81–92.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jacobs, Steven Leonard (2017). "I G Farben". In Bartrop, Paul R.; Dickerman, Michael (eds.). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection. Volume 1. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. pp. 312–314.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jeffreys, Diarmuid (2008). Hell's Cartel: IG Farben and the Making of Hitlers War Machine. New York: Metropolitan Books-Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-9143-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lifton, Robert Jay; Hackett, Amy (1998). "Nazi Doctors". In Berenbaum, Michael; Gutman, Yisrael (eds.). Anatomy of the Auschwitz Death Camp. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 301–316.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schmaltz, Florian (2018). "Auschwitz III—Monowitz Main Camp [aka Buna]". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945, Volume 1. Bloomington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Indiana University Press. pp. 215–220.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Neumann, Boaz (2012). "National Socialism, Holocaust, and Ecology". In Stone, Dan (ed.). The Holocaust and Historical Methodology. New York: Berghahn Books.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nicholson, John W. (2006). The Chemistry of Polymers. London: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-0-85404-684-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Records of the United States Nuernberg War Crimes Trials, United States of America v Carl Krauch et al. (Case VI)" (PDF). National Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 July 2017.

- Rees, Laurence (2006) [2005]. Auschwitz: A New History. New York: PublicAffairs.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sasuly, Richard (1947). IG Farben. New York: Boni & Gaer.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schwartz, Thomas Alan (2001) [1994]. "John J. McCloy and the Landsberg Cases". In Diefendorf, Jeffrey M.; Frohn, Axel; Rupieper, Hermann-Josef (eds.). American Policy and the Reconstruction of Germany, 1945–1955. Cambridge and New York: German Historical Institute and Cambridge University Press. pp. 433–454.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Spicka, Mark E. (2018). "The Devil's Chemists on Trial: The American Prosecution of I.G. Farben at Nuremberg". In Michalczyk, John J. (ed.). Nazi Law: From Nuremberg to Nuremberg. London and New York: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-350-00724-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Stokes, Raymond (1994). Opting for Oil: The Political Economy of Technological Change in the West German Chemical Industry, 1945–1961. New York: Cambridge University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Strzelecka, Irena (2000). "Experiments". In Długoborski, Wacław; Piper, Franciszek (eds.). Auschwitz, 1940–1945. Central Issues in the History of the Camp. Volume 2: The Prisoners, their Life and Work. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Tammen, Helmuth (1978). Die I.G. Farbenindustrie Aktiengesellschaft (1925–1933): Ein Chemiekonzern in der Weimarer Republik (in German). Berlin: H. Tammen. ISBN 978-3-88344-001-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, October 1946 – April 1949" (PDF). VIII: "The I. G. Farben Case". Washington, D.C.: Nuernberg Military Tribunals, United States Government Printing Office. 1952. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - The United Nations War Crimes Commission (1949). "Law Reports of Trials of War Criminals. Volume X: The I.G. Farben and Krupp trials" (PDF). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 1–67. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 December 2008.

Further reading

Books and articles

- Bernstein, Bernard (1946). "Elimination of German Resources for War". Washington, D.C.: United States Department of War, United States Government Printing Office.

- Borkin, Joseph (1943). Germany's Master Plan: The Story of the Industrial Offensive. New York: Duell, Sloan And Pearce.

- Borkin, Joseph (1990). Die unheilige Allianz der IG Farben. Eine Interessengemeinschaft im Dritten Reich (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag. ISBN 978-3-593-34251-1.

- Bower, Tom (1995) [1981]. Blind Eye to Murder: Britain, America and the Purging of Nazi Germany—A Pledge Betrayed (2nd revised ed.). London: Little, Brown.

- Cornwell, John (2004). Hitler's Scientists: Science, War, and the Devil's Pact. London: Penguin Books.

- Dubois Jr., Josiah E. (1952). The Devil's Chemists (PDF). Boston, MA: Beacon Press. ASIN B000ENNDV6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2011.

- Du Bois, Josiah Ellis; Johnson, Edward (1953). Generals in Grey Suits: The Directors of the International 'I. G. Farben' Cartel, Their Conspiracy and Trial at Nuremberg. London: Bodley Head.

- Higham, Charles (1983). Trading With the Enemy. New York: Delacorte Press. ISBN 978-0-440-09064-9.

- Karlsch, Rainer; Stokes, Raymond G (2003). Faktor Öl: die Mineralölwirtschaft in Deutschland 1859–1974 (in German). Munich: C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3-406-50276-7.

- Kreikamp, Hans-Dieter (1977). "Die Entflechtung der I.G. Farbenindustrie A.G. und die Gründung der Nachfolgegesellschaften" (PDF). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). Munich: Oldenbourg Verlag. 25 (2): 220–251. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- Lesch, John E., ed. (2000). The German Chemical Industry in the Twentieth Century. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

- Moonman, Eric (21 November 1990). "Shares spoil (letter)". The Guardian. p. 18.

- López-Muñoz, F.; García-García, P.; Alamo, C. (2009). "The pharmaceutical industry and the German National Socialist Regime: I.G. Farben and pharmacological research". Journal of Clinical Pharmacy and Therapeutics. 34 (1): 67–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00972.x. PMID 19125905.

- Maguire, Peter (2010). Law and War: International Law and American History. New York: Columbia University Press.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Plumpe, Gottfried (1990). Die I.G. Farbenindustrie AG: Wirtschaft, Technik und Politik 1904–1945 (in German) (Schriften zur Wirtschafts- und Sozialgeschichte ed.). Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. ISBN 978-3-428-06892-0.

- Sandkühler, Thomas; Schmuhl, Hans-Walter (1993). "Noch einmal: Die I. G. Farben und Auschwitz". Geschichte und Gesellschaft (in German). 19 (2): 259–267. JSTOR 40185695.

- Stokes, Raymond (1988). Divide and Prosper: The Heirs of I.G. Farben under Allied Authority, 1945–1951. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tenfelde, Klaus (2007). Stimmt die Chemie? : Mitbestimmung und Sozialpolitik in der Geschichte des Bayer-Konzerns. Essen: Klartext. ISBN 978-3-89861-888-5

- Tully, John (2011). The Devil's Milk: A Social History of Rubber. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Wagner, Bernd C.; Frei, Norbert; Steinbacher, Sybille; Grotum, Thomas; Parcer, Jan, eds. (2000). Darstellungen und Quellen zur Geschichte von Auschwitz, 4 volumes. Munich: K.G. Saur.

- White, Joseph Robert (1 October 2001). ""Even in Auschwitz... Humanity Could Prevail": British POWs and Jewish Concentration-Camp Inmates at IG Auschwitz, 1943–1945". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 15 (2): 266–295. doi:10.1093/hgs/15.2.266.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to IG Farben. |

- Documents and clippings about IG Farben in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- Official website of the IG Farben successor BASF

- Official website of the IG Farben successor Bayer

- Official website of the IG Farben successor Hoechst (now Sanofi-Aventis)

- Stock Market Prices of IG Farben

- "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals under Control Council Law No. 10, October 1946 – April 1949" (PDF). VIII: "The I. G. Farben Case". Washington, D.C.: Nuernberg Military Tribunals, United States Government Printing Office. 1952. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)