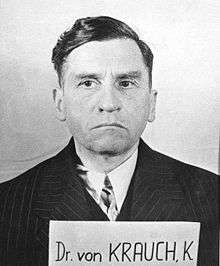

Carl Krauch

Carl Krauch (7 April 1887 – 3 February 1968) was a German chemist, industrialist and Nazi war criminal. He was an executive at BASF (later IG Farben); during World War II, he was chairman of the supervisory board. He was a key implementer of the Reich’s Four-Year Plan to achieve national economic self-sufficiency and promote industrial production. He was Plenipotentiary of Special Issues in Chemical Production, a senator of the Kaiser Wilhelm Society, and an honorary professor at the University of Berlin. He was convicted in the IG Farben trial after World War II and sentenced to six years in prison.

Education

From 1906 to 1912, Krauch studied at the Justus Liebig-Universität Gießen and the Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. From 1911 to 1912, he was an unpaid teaching assistant to R. Stallé at Heidelberg. He received his doctorate in 1912 under Theodor Curtius at Heidelberg.[1]

Career

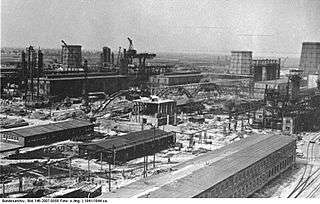

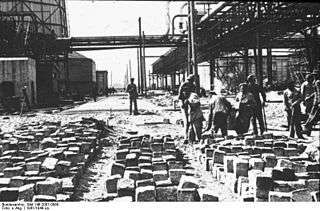

From 1912, Krauch was employed at BASF, later I.G. Farbenindustrie AG. He was a longstanding member of the board and general committee, and chairman of the supervisory board, 1940 to 1945, succeeding Carl Bosch as chairman. From 1936, Krauch was head of the Research and Development Department of the Amt für Deutsche Roh- und Werkstoffe. From 1939, he was head of the renamed Reichsamtes für Wirtschaftsausbau (Reich Office for Economic Expansion), established in 1936 as part of the Four-Year Plan to achieve national economic self-sufficiency and promote industrial production especially for rearmament. The Amt für Deutsche Roh- und Werkstoffe was nicknamed the Amt für IG-Farben Ausbau ("Office for the Expansion of IG Farben"), due to his dual head positions.[1][2][3]

From 1938 to 1945, Krauch was Plenipotentiary of Special Issues in Chemical Production and a member of the board of the Reichsforschungsrat (RFR, Reich Research Council). Additionally, he was an honorary professor at the Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität (later, the Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin). Krauch was also a member of the Senate of the Kaiser-Wilhelm Gesellschaft (KWG, Kaiser Wilhelm Society).[1][4]

Krauch was a member of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist Workers Party) from 1937.

I G Farben trial

He was a defendant in the post war IG Farben Trial, found guilty of the indictment of "War crimes and crimes against humanity through participation in the enslavement and deportation to slave labor on a gigantic scale of concentration camp inmates and civilians in occupied countries, and of prisoners of war, and the mistreatment, terrorization, torture, and murder of enslaved persons." and given a six-year prison sentence.[1][5] He was released in 1950. After that, he became a member of the supervisory board of the Bunawerke Hüls GmbH. In the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials, as a witness on 19 February 1965, he denied all knowledge of the events in Monowitz, part of the Auschwitz complex and designed to produce synthetic fuel and butadiene rubber. Carl Krauch died on 3 February 1968.[6]

Bibliography

- Hayes, Peter Carl Bosch and Carl Krauch: Chemistry and the Political Economy of Germany, 1925–1945, Journal of Economic History Volume XLVII, Number 2, 353-363 (June 1987)

- Hentschel, Klaus (Editor) and Ann M. Hentschel (Editorial Assistant and Translator) Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Birkhäuser, 1996)

- Krauch, Carl Jugend an die Front. Die Nachwuchsfrage in Wissenschaft und Technik, Der Vierjahresplan, Volume 1, 8th Series, August 1937, pp. 456 – 459. This document was translated and republished in Klaus Hentschel (Editor) and Ann M. Hentschel (Editorial Assistant and Translator) Physics and National Socialism: An Anthology of Primary Sources (Birkhäuser, 1996) 161 - 168: Document 58, Carl Krauch: Youth to the Front Line. New Blood in Science and Technology [August 1937].

- Macrakis, Kristie Surviving the Swastika: Scientific Research in Nazi Germany (Oxford, 1993)

References

- Hentschel and Hentschel, 1996, Appendix F; see the entry for Krauch.

- Hentschel and Hentschel, 1996, 162n5.

- Macrakis, 1993, 102-103.

- Macrakis, 1993, 136.

- Krauch, 1937, Document 58, in Hentschel and Hentschel, 1996, .

- Wollheim Memorial